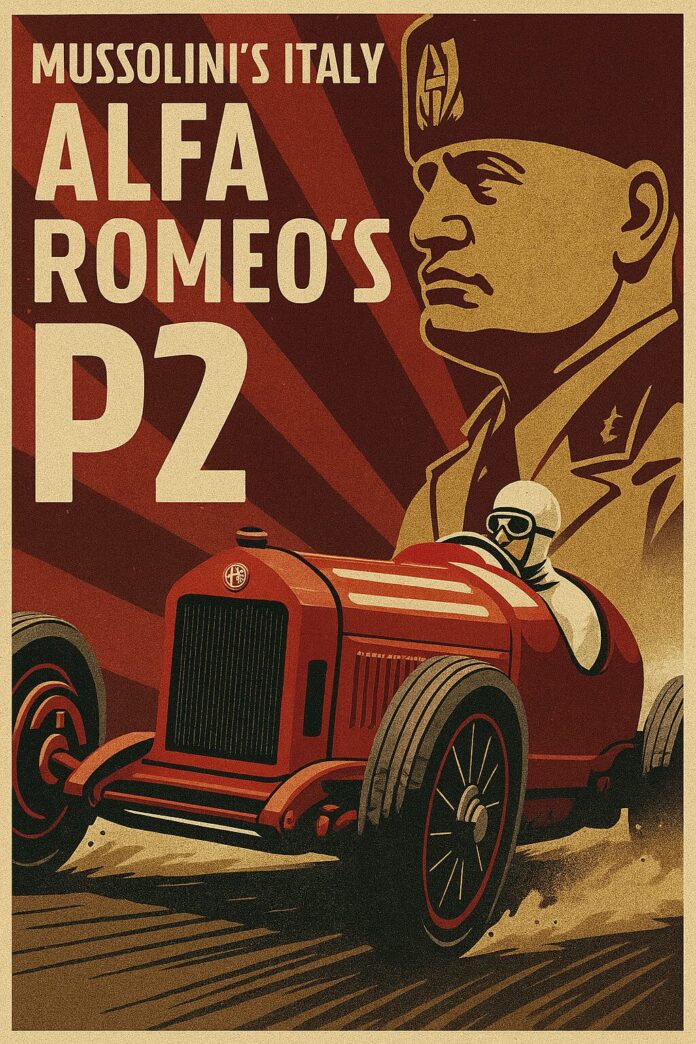

As Italy approached the centennial of the Alfa Romeo P2’s debut, it’s worth revisiting the legacy of a car that was far more than a racing machine. Designed by Vittorio Jano and championed by a young Enzo Ferrari, the P2 wasn’t just fast – it was a political and cultural icon, forged in the crucible of Mussolini’s Italy.

The P2’s rise mirrored a broader industrial and ideological shift. Milan, home to Alfa Romeo, was cast by fascists as youthful and dynamic, in contrast to the staid, liberal Turin of Fiat. Fascist publications like La Vista del Popolo framed Alfa as the audacious future, Fiat as the outdated past. Alfa’s victories on the track became metaphors for Mussolini’s political revolution.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

Alfa’s first major international win came at the 1923 Targa Florio, just months after Mussolini became Prime Minister. Coincidence or not, the regime seized on the moment. When Giuseppe Campari won the 1924 European Grand Prix at Lyon, the announcement interrupted a tense fascist party meeting in Rome. The next day, Italy’s leading newspaper placed the race win alongside political headlines – a symbolic pairing of speed and state.

Designed in record time by Jano and his youthful team, the P2 embodied fascist ideals of discipline, innovation, and velocity. Ferrari, then just 25, recruited the talent and shaped the team’s ethos. The car’s aesthetic echoed Fiat’s 805, but its engine and suspension were refined to deliver superior performance – an act of industrial revenge against Ferrari’s former employer.

Spotlight

Paul Baxa is Professor of History at Ave Maria University in Florida. Parts of his most recent book, Motorsport and Fascism: Living Dangerously have been presented at past Argetsinger Symposia. He was privileged to have presented at the first symposium in 2015.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, our History of Motorsports series, discusses the Alfa Romeo P2, an iconic racing car designed by Vittorio Jano that debuted 100 years ago. The P2 dominated Grand Prix racing during the two-liter formula in the mid-1920s, helping Alfa Romeo win the first World Championship in 1925. The presentation, delivered by Paul Baxa, explores the broader industrial, cultural, and political significance of the P2 beyond its sporting achievements, particularly its role in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy. The P2’s victories were used by Mussolini’s regime to symbolize Italy’s industrial revival and national pride, while also influencing motorsport culture and politics during that era. The narrative touches on the car’s design, its impact on Italian motorsports, and the personal stories of key figures like Antonio Ascari and Enzo Ferrari. The Alfa Romeo P2 remained successful in racing through the 1930s and eventually became a symbol of Italy’s motorsport legacy.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports Series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer family.

Crew Chief Eric: The P two Alpha Fascist Icon by Paul Bax. This year, we’ll mark the hundredth anniversary of the iconic Alpha Romeo’s P two’s debut, designed by legendary Vitor Yano.

The P two went on to dominate Grand Prix racing in the final two years of the two Leader Formula. In 1925, alpha Romeo won the first World Championship, after which the team dually withdrew from the sport. However, privately owned Alpha P Twos continue to participate in racing and win races up until 1930.

The sporting achievements of the Alpha P twos are well known as is the role the car played in establishing Alpha Romeo as Italy’s most famous racing mark. Up until the advent of the Second World War, less known is the broader significance of the P two that went well beyond the [00:01:00] racetrack. Informed by the history of objects developed by cultural historians.

This paper argues that the P two significance was industrial, cultural, and ultimately political. The achievements of the P two and the emergence of the mil based alpha company coincided with the establishment of Mussolini’s dictatorship in Italy. The fascist regime used the successes to celebrate the rise of fascist Italy as an industrial and sporting power.

Moreover, the unique characteristics of the P two came to embody the values promoted by fascism such as speed and dominance, both the design and performance of the car, as well as the men who raced. It came to shape not only Grand Prix racing in the 1920s, but also impacted the role played by the sport in the political and cultural context of fascist Italy.

Paul Baxa is a professor of history at Ave Maria University in Florida. Parts of his most recent book, motor Sport and Fascism Living Dangerously have been presented at past Argen Singer Symposia. He was privileged to have presented at the first symposium in 2015.

Kip Zeiter: Thanks everybody. I’d like to introduce you to our next [00:02:00] speaker, Paul Baxa, who’s going to talk about the P two Alpha fascist icon.

Thank you, Kip.

Paul Baxa: Thank you all. Uh, I wanna thank Don Kas and Bob Barr and Duke Kininger and everyone who make this great event happen. It was my privilege to be at the first one back in 2015 and it’s amazing how this has grown. Thank you for having me. Just, uh, before I get to my presentation, Jim had a, uh, slide showing the program for the 1980 US Grand Prix.

I had the privilege of being at that race back in October of 1980. I came down with my dad. I remember. Bruno Giac in the Alfa Romeo Getting Pole position, and I came from a family of Tizi, but my dad told me that weekend, he said a, you know, a real Italian racing fan knows that Alfa Romeo is really the team to cheer for.

And that leads me actually to today’s presentation. Actually. My dad grew up in fascist Italy, so he may have been influenced by some of the things I might be talking about today. [00:03:00] So on Sunday, August 3rd, 1924, the fascist party of Italy was holding an emergency meeting in the Palazzo Venetia in Rome. It was the height of the Mati crisis, and Mussolini’s government was facing an uncertain future.

The body of the socialist deputy, Giacomo Mati was still missing after he was kidnapped by a group of fascist thugs in June. Although his fate was unknown, the expectation was that Mati had been assassinated and that Mussolini was to blame. At 5:00 PM during a series of tense exchanges and speeches, calling for Mussolini to crack down on his enemies, the radical fascist.

Francesco Junta interrupted the conference to announce that Giuseppe Camp driving a P two Alfa Romeo had just won the European Grand Prix at Leon. The next day, the front page of Italy’s most important national newspaper carried two items, the PNF meeting and the Grand Prix in its report of the party meeting, the article noted Junta’s announcement.

It [00:04:00] was a bright light and an otherwise darkening situation from Mussolini and his government. 10 days after camp stirring victory, Mattel’s body was discovered in a shallow grave north of Rome. As it turned out, Mussolini’s regime not only survived the crisis, but it became the jumping off point for his dismantling of Italian democracy and the establishment of the fascist dictatorship.

In the meantime, the P two alphas would go on to dominate Grand Prix racing during the two liter formula and beyond. To be sure the victories of the Alphas led by the charismatic Antonio Ascotti served as a distraction from the tumultuous events in Italy. They were also used by Mussolini to exalt the New Italy that he and his fascists were in the process of building.

In the pages of Italy’s most Read Illustrated magazine, the lead editorial in the next edition noted how the common man was more interested and excited by the exploits of the Alphas than they were by the sorted events of Roman politics. Victory at Leon [00:05:00] was far more important it seemed than the disappearance of a socialist politician.

The car at the center of this was the P two Alfa Male’s First Grand Prix winning machine. Designed by Vittorio Yano and Record Time. The car was introduced at the Remona Grand Prix in June of 24. Results was an easy victory in the hands of Antonio Ascotti. With it came a new speed record on the circuit’s 10 kilometers straight, clocked at 121 miles per hour.

The car and the company that built it quickly became a symbol of Italy’s rebirth under the sign of fascism. This paper will demonstrate the correlation between the P two, its design and its successes with the rise of Italian fascism in the decisive years between 1924 and 1930. In those years, Mussolini consolidated his dictatorship and promoted sport as one of the regimes greatest achievements.

At the Party Congress in August, Mussolini gave a speech where he declared that it was time [00:06:00] for Italians to live dangerously. Present at that meeting was Roberto Farci, the violent fascist chief of Cremona and leader of the intransigent wing of the party. Faade Naci was also a some time race car driver and promoter of the Remona Grand Prix.

Apart from Mussolini, no one embodied fascist violence and the cult of speed more than Faade. Naci, a man who approved the TIS assassination and called for even more bloodshed. The fact that the P two began its legendary run of successes on his patch of lumber de. Seemed fitting, especially as the Remona Road Course was known for being one of the fastest racetracks in the world.

In his book, objects of Desire, a study of Italian industrial culture in the late 19th and early 20th century, Luca Tini has argued that objects are culture makers mediating devices. And vehicles of meaning. In the 1920s, Kini argues Italian industrial design reached a peak of expressive energy [00:07:00] that was found mostly in the aviation and automobile industries.

Two modern activities exalted by fascism. In addition, thanks to design theorists like Joe Ponti, Italian industrial products became works of art as well as commercial objects. I would add that they also became political objects, vehicles to draw Italians to Mussolini’s dictatorship in the late 1920s, precisely the period that Kini points out as the culmination of Italy’s developing industrial culture and entrance into modernity.

No object expressed this network of relations. I argue more than the P two. The link between the successes of the Alpha Maleo P two and national industrial political revival was even noted by foreign journalists. After a crushing demonstration of dominance in the 1925 European Grand Prix at spa, the Dean of French Motorsport, writers Shao Faru, exclaimed how the Alfa Romeo Squad embodied the Italian National Renaissance.

Those are the words that he used. [00:08:00] Before I came to represent Italy’s political shift, the P two caused a qualitative shift for its company and a major shift in Italian motorsport. Based in Milan, Italy’s emerging industrial and financial capital. Alpha’s victory in the 24 French Grand Prix effectively knocked fiat out of Grand Prix racing for good.

Although, to be fair, I think Fiat was, had already essentially made the decision to leave before that. Fiat had represented racing success for Italy since the early 19 hundreds, and was the country’s leading automobile manufacturer aspiring to become Italy’s Ford. Ali’s company was based in Tarin Milan’s rival for industrial prowess.

Alpha’s victories, therefore not only represented success on the track, but also symbolized Milan’s challenge to the Piedmontese capital. In doing this, alpha was accomplishing an industry what Mussolini’s movement was doing in politics. Like Alpha Fascism was born in Milan, a city that presented itself as a more dynamic and youthful one compared [00:09:00] to the state city of Turin.

A city described by some fascists as filled with sticks in the mud quote. After winning the 1924 Italian Grand Prix, the Fascist magazine, LA Vista del Popolo contrasted the young audacious alpha with the old Fiat end quote. Like the cities, the two companies were often presented in contrasting ways by the fascists.

Turin and Fiat were throwbacks to the old liberal Italy. Well, alpha and Milan were part of the new avant-garde Italy. Fascism’s relationship with Turrin and Fiat was a difficult one. Giovanni Ali, Fiat’s founder was not a fascist, and the company’s labor force was mostly anti-fascist. Alpha, on the other hand, was a smaller, younger company, and its labor force would become home to former black shirts.

Fiat was the past, alpha was the future. Nothing embodied this more than the P two project. Everything about the P two, the men who built and raced it, and the successes on [00:10:00] the track corresponded to Mussolini’s new image for Italy. Up until 1924, Alfa Romeo had limited success on international racetracks.

Its success seemed to coincide with the rise of the regime. Alpha’s first major victory came at the Targa Florio in 1923, international victory. Only a few months after Mussolini became Prime Minister of Italy, which of course is. Pure coincidence, but it was something that was commented upon that same year.

The design and engineering department of the Mil outfit was completed with the arrival of Vittorio Yano from Fiat. It was Yano and his team of engineers who put together the P two project in record time. Both the speed of the project and the youthfulness of the team fit in with Fascism’s cultivation of speed and youth.

Both Yano and Luigi Basi, who had also come over from Fiat were in their thirties. Meanwhile, the man most responsible for bringing these men into the alpha fold. Enzo Ferrari was only 25 years old, according to Peter Hall and Luigi Fuzzi [00:11:00] Ferrari was the driving force by an alpha’s assembling of a crack designing team.

Ferrari represented everything that Mussolini’s regime, ext stalled in Italy. He held from the same region as Mussolini and came from a similar modest background. After serving in the First World War, Ferrari had applied for a job at Fiat, but was turned down in later years. He would describe this moment as a turning point in his life as fate would drive him to Milan, where he eventually joined the fledgling Alpha Company.

Ferrari’s story thus resembled the profile of the ideal fascist in some ways, as one who was rejected by the establishment and then turned that frustration into revenge. In Ferrari’s case, the revenge came with knocking Fiat out of racing. The development of the P two was born out of a similar set of frustrations.

Yano was part of the design team that had put together the Fiat 8 0 5 a car that was the class of the field in 1923, but it failed to win the French Grand Prix, which is the most important [00:12:00] international race at the time. Aware of the car’s weaknesses, Yano was not able to rectify them due to his subordinate position within the team.

At Alpha, he would use the P two project to improve on the Fiat. In his time at Fiat, Yano was shackled by the corporate structure of the company and the fact that Fiat emphasized. Its production cars over racing. Alpha, on the other hand, was smaller with an increasing emphasis on high performance sports cars.

At Alpha Yano was able to instill a military-like discipline that suited the type of rhetoric that was being pumped out by Mussolini’s, Italy. He joined the team in September of 23, and the first drawings for the car were completed by mid-October. The following March saw the first engine put on the test bed, and in June, the first example was taken to Monza and tested by Antonio Scottie and Giuseppe Compati just a few days before it won at Cremona.

The speed of the car’s production was helped by the fact that Yano was merely perfecting the Fiat 8 0 5. He had worked [00:13:00] at in Turin, modifications on engine and suspension design helped produce a car that was more powerful and ultimately faster than the 8 0 5 without the reliability issues aesthetically.

The P two was almost a carbon copy of the Fiat, but the modifications to the engine were significant to the point where Yano later claimed that the car was a completely new design. That was his claim. In this case, unintentionally, the P two did resemble Mussolini’s movement. Fascism two was largely derivative, appropriating preexisting ideas and concepts while claiming to create a new Italy.

P two’s successes on the track however, appeared to usher in a revolution while the REM Grand Prix demonstrated the new car’s potential, it was the Grand Prix Leon that consecrated the P two in the eyes of Mussolini’s New Italy. The stage could not have been more appropriate. Beginning in 1923, the governing body of Motorsport anointed one National Grand Prix.

To have the title of European Grand Prix in [00:14:00] 1924 was the turn of the Grand Prix de France, or the Grand Prix de la cf. Strictly speaking, ALS known as the French Grand Prix. Furthermore, the 1924 edition of the Race was a special one since it marked the 10th anniversary of the Epic 1914 race that saw the French and German teams battle on the track only weeks before the outbreak of the First World War.

As a commemoration of that event, the race returned to the Leon Vo circuit, the scene of that historic race in 1914. The event thus served to remember a great race, but also served as a memorial to the war. A fact that fed the fascist regime’s own exaltation of the war experience. The resulting race was nearly as epic as its 1914 predecessor on the Spectacular Road Course.

It wasn’t exactly the same by the way. They cut it in half, so they used half of the original course, but they used the most exciting part on The Spectacular Road Course. Alfa Romeo Fiat, Sunbeam de Lodge, and Bugatti [00:15:00] battled for over seven hours in a race that went back and forth with numerous lead changes with Compati Alpha emerging triumphant.

Giuseppe Camp’s Victory at Leon Made Alfra Romeo a national name and was able albia briefly to serve as a distraction from the mati crisis. As I already mentioned, the car appeared in ads for the company and for Pelli the tire manufacturer. This poster calls the race the Olympiad of engines. The P twos triumphant, Leon encouraged a more bullish attitude on the part of Italy’s representatives at the sporting Commission of the A-I-A-C-R, which is the forerunner of the FIA, taking advantage of a procedural loophole.

The Italian representatives tried to convince the commission to award the title of European Grand Prix in 1925 to Italy and not to Belgium as had been approved by the A-I-A-C-R in its previous general meeting. Claiming that Italy had the stronger racing tradition proven by office victory. At Leon [00:16:00] Arturo Meti, one of the two representatives argued that Italy deserved the race, not Belgium.

The challenge which caused some friction at the sporting commission’s meeting in the fall of 24, was unsuccessful. However, the Italian delegation did succeed in persuading the sporting commission to create a world championship for manufacturers in 1925. The desire to use Alpha’s triumphs to elevate Italy’s international motorsport.

Prestige mirrored the fascist regime’s, attempts to make Italy into a world power. In 1925, Mussolini turned to the dismantling of the Italian liberal state in the wake of the Mati assassination, an event that should have been his end, but instead marked the beginning of fascist. Italy’s rise to power.

The new secretary of the fascist party was none other than Roberto Farci, the patron of the Cremona Grand Prix. An intransigent fascist who now aim to activate Mussolini’s call for living dangerously. The events on the [00:17:00] racetracks of Europe reflected the radical and violent shift in Italian politics.

1925 was to be the last year of the successful two leader formula and alpha set its sight on dominating the opposition in three races. The European Grand Prix at spa, the French Grand Prix at the new Mulla Auto Drum and the Italian Grand Prix at Monza Alpha’s approach to these races involved a degree of swagger and even arrogance.

They lapped the field at spa prompting jeers from the partisan crowd. After crossing the line, Scotty’s car had a giant Italian flag placed on the hood. Uh, there is a story about this race that I didn’t find any of the contemporary accounts, but it kind of was told later by Motorsport historians that in order to taunt the crowd, the alphas, because they had lapped everybody and I think all the French cars had dropped out.

Actually, and so there was just two alphas kind of circulating in the last part of the race. At one point they made such a lengthy pit stop that they took out a table and laid out a [00:18:00] food spread. Um, it’s a great story. It might be apocryphal though, because I didn’t find it in contemporary counts, and Giovanni kind of Sini was kind of one of the Dean of Motorsport.

Historians later said it wasn’t really like that, it was just simply, you know, they had some panini, you know, sandwiches ready. Pit stops took a bit longer than usual. So it, you know, Scotty and Campti had timed it down a, you know, a sandwich and that’s really all it was. But it’s one of those wonderful stories, but it might be apocryphal.

Whatever, though it still shows a certain degree of swagger, whatever it was, uh, on the part of the Alpha team. The Alphas were also dominating the French Grand Prix until Antonio Ascotti crashed and was killed while leading the race. Prompting the team to withdraw from the race as a final gesture of defiance, the two remaining alphas revved their engines loudly before leaving the race, and that is in a contemporary account.

Uh, so they stopped in the pits and they started revving their engine. Now that was probably a salute to a Scotty, but again, you can’t interpret that as kind of a [00:19:00] defiant gesture. It was, uh, Bri Petty Gu, BLI Petty who gave Alpha the World Championship when he won the Italian Grand Prix in September. No one represented the new order in Grand Prix racing better than Antonio Hasti.

His name became synonymous with the P two and with the Living Dangerously motto promoted by Mussolini and Fad naci. It had given the P two, its verse of Victory at Cremona and one at Manza in 1924 and its SPA in 1925. More than his victories. He came to embody a certain aggressiveness in his driving. He would be the first example of what would later be called the Gati Baldino approach to racing.

That’s a reference to Giuseppe Gati bdi, the guy who helped unify Italy. This Gati Baldino tag is most famously embodied by the likes of Tatio NTI in the 1930s, but as Scotty really was the first to kind of get that reputation. In short, he took risks. Amanza in 1924, his driving prompted a rebuke from the race director who instructed [00:20:00] Alur to slow him down or they would call him in.

This is the telegram that was sent from the race director who was Arturo Meti to the Alur MEO PIP saying, tell us Gotti to slow down. Otherwise we’re gonna call him in. It’s ’cause he was on the banking. He was going too close to the guardrail at the top. His style of driving ultimately proved his undoing while dominating the French Grand Prix.

In 1925, he continuously brushed the apex of a fast left hand turn, coming with an inches of a wooden fence. On lap 22, he came too close, clipping the fence and rolling the car, which led to his death. A Scotty’s death and Moni resulted in an outpouring of grief and a state funeral. In Milan, he became fascist.

Italy’s first racing martyr, and that word was in fact used when his body returned to Italy on a train. A large wreath from Mussolini was placed on the casket across the wreath that was donated by Mussolini were the words repi the intrepid. The funeral [00:21:00] card repeated Mussolini’s epithet with a message that read Antonio Ascotti, the Intrepid one, who sacrificed himself defending with undefeated faith, the colors of the Fatherland and Italian industry, although he had been racing since the 1910s, as Scotty’s memory is indelibly marked with the P two.

Not only did the car symbolize Trium. But it now also created martyrs speed and death in the service of glory. Found echoes in fascist rhetoric. The response to a Scotty’s death and his depiction as a martyr to speed became the response template for the numerous Italian drivers killed in Grand Prix racing over the next decade.

But none of them would be as celebrated as a Scottie, which showed a great deal to the Alpha Romeo P two. And in fact, um, I don’t. Have a hard number in my head, but Italy probably produced more dead race drivers in the late twenties and thirties than any other country, but I, I can’t say that for certainty, but there were a number of Italian drivers who were killed in that period.

Unwilling [00:22:00] to build a new car for the new one and a half liter formula Introduced in 1926 and troubled by financial problems. Alpha withdrew from Grand Prix racing after the 25 season. The legend of the P two continued on though as the car would enjoy an afterlife that kept it winning races until 1930.

Mostly run by the SC Ferrari. In 1928, the A-I-A-C-R introduced the formula Libra Rules, which allowed this car to enter the official Grand Prix races. It was in this era that the legend of the car actually deepened in the late twenties Grand Prix racing entered a period of doldrums. Indicative of this was the fact that there was only one Grand Prix race held in 1928 at Manza.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Italy saved the sport or Grand Prix racing in particular in these years with the P two right at its center at Manza. All the attention of the Italian press, especially the newspapers closely associated with the fascist party, focused on [00:23:00] the P two, driven by Akili Zi.

In 1929, the cars were run by the new Kuia Ferri, where former Alpha personnel like Ferrari and Luigi Bati were reunited with the P twos in 1930. The P twos are driven by Akili, Zi and Tazi nti. Thus launching what was to become the most legendary driver rivalry in Italian motor sports in the 1930s, probably of all time.

One last epic victory came at the Targa Florio in 1930 in the hands of Akili Tazi. By 1930, the P two had been substantially modified. This included the adoption of the flat slanted radiator taken from the Alpha 1,517 50 sports car models. These cars, which brought alpha more glory in the Mil Melia races were directly inspired by the P two.

According to the Alpha Romeo historian Peter Hall, this made Alpha the only mark, which directly transferred Grand Prix technology to sports cars and vice versa. That’s. Peter Hall’s [00:24:00] claim the introduction of the high performance six cylinder sports cars. Also designed by Vito Ano made alpha the most prestigious Italian maker of sports cars into the 1930s in Italy and worldwide, possibly thus establishing itself as the mark most suitable to the fascist era and Mussolini’s regime building a process that was completed by 1929.

As the modified P twos raced into their swansong year of 1930, fascism had completed the dismantling of the liberal state, and sport had become completely fasc size fiat. In the meantime, after an aborted attempt to return to Grand Prix racing in 1927 turns its attention to mass produced utility vehicles.

A turned to the masses that would shape fascist policy in the thirties. As fascist Italy entered the decade of the thirties, alpha Romeo become closely identified with Mussolini. He called Alpha Romeo our best national product, and it was increasingly seen at the wheel of an alpha. Here he is driving, I believe, let’s say 1750 [00:25:00] around the new, um, litorial Autodrome in Rome, which is a purpose built track in Rome, which no longer exists.

It’s now an airport. In 1951 with Italy embroiled in a war that was going from bad to worse. Alfa Romeo’s magazine published a retrospective on the P two written by Rado Filip, one of Italy’s leading Motorsport journalists. This article summed up the importance of the P two for Italy’s national prestige.

The two years of Alpha Domination in 24 and 25 were characterized by Filip as the most spectacular era of Italian genius. Ignoring the fact that the P two was largely based on the Fiat 8 0 5, the retrospective claim that the P two had set a new standard for race car design, calling it authentically avant-garde.

For NY proof of the car’s greatness came in the 28 19 30 period when this older car was beating newer cars. Sometimes. Moreover, NY was confident that the car could even hold its own [00:26:00] against contemporary competition. That would be auto unions and Mercedes. So. Make of that what you will hyperbole aside. A Philipp’s article demonstrated the continued legacy of a car that had elevated Italy to the top of Grand Prix racing in an era when Mussolini’s fascist regime was being constructed in peace time Alfa Mayo contributed to the triumphs of Italy on the track.

In 1941, Alpha’s production was directed to the war effort, and although the Italians are struggling on the battlefield, its access partner was walking all over Europe. For Philippines readers memories of the P two could be harnessed in the hope that Italian technology could once again triumph, while history would demonstrate otherwise.

Thank you.

Kip Zeiter: Thank you Paul. That was fascinating. Anyone have questions? We have a question from the internet for Paul Terry

Crew Chief Eric: Johnson writes, are there any P two alphas currently appearing at vintage and or historic events?

Paul Baxa: Uh, I don’t know if they appear at events, [00:27:00] but I think there are still two in existence. There’s a, an original P two, the first spec of the P two in the Alpha Mayo Museum in re.

And there is one of the later P twos at the um, automobile museum in Torino or Turin, so I know that they exist. I don’t know if they take them out on the track though.

Audience Q&A: I’m just interested in your commentary on the state sponsorship of Alpha Rome or other Italian motor manufacturing and how this episode plays into that.

If it does or if it does not.

Paul Baxa: Yeah, that’s an important question. The fascist regime did not subsidize the racing teams the way the Nazi regime did, but Mussolini did intervene on a few occasions to save the company from bankruptcy. In 1933 though, uh, alpha Mayo was taken over by the, it was bailed out by the IRI, which was the state run bailout institution.

So after 33, it did become a state owned. Team, but it wasn’t racing officially as a works team. Alphas were always raced by the Ferrari. However, [00:28:00] in 1938, they did come back as an official team, alpha corse. So in that sense, yes it was because it was effectively owned by the state at this point. So. I dunno if that answers your

Jim Miller: question, Paul.

It turns out I have something of a follow up question, which is to compare, if not narrowly, regarding finances, the Nazi use of symbolism in racing during this time with the Italians.

Paul Baxa: In, in what sense are they equally

Jim Miller: active, more successful in using, uh, auto racing as a a means of political expression or.

Paul Baxa: Oh yes. Yeah. Uh, absolutely. The Nazi regime, of course, would very much celebrate its victories. Uh, the, the German cards, victories, and, um, Italy did the same for the, um, Motorsport magazines, but even in the national newspapers, there would always be front page coverage when Alpha won a race. So you did have a similar type use of propaganda.

For the races. Absolutely.

Audience Q&A: When Fascist, Italy no longer existed, did Alpha Romeo struggle to shift any kind of negative associations with it, or was it relatively smooth sailing?

Paul Baxa: They [00:29:00] were able, I think, to shift rather easily into the postwar, and that that goes with any sporting hero. Actually under fascism.

Even the great cyclists like Bartley and the soccer teams, they were all able to really easily transition. Uh, Simon Martin, uh, a sports historian, non Italian. Sports history makes this argument. I mean, it shows that the sporting heroes were able to create their own kind of popularity or their own niche in the Italian imagination that transcended fascism.

So perhaps going back to Jim’s earlier question that shows that maybe the regime was not as successful ultimately in making it truly fascist. I have to say though, that the managing director of Alfa Romeos name was Ugo GoTo, and he was, uh, he was appointed by Mussolini. After the state took over the company in 33, he was assassinated by the Italian resistance in 1945.

And so not to be cynical, but I think by getting rid of him, even though he was not, as far as I know, he was not a convinced fascist. In fact, he had an industrial background. He had [00:30:00] worked for Fiat. He had actually designed the lingo Hotel factory in Tur, if you’re familiar with that. But he kind of paid the price, if you will, for Al Alpha Rome’s association with the regime.

So maybe that was enough to make others forget. And keep cheering for Al Romeo. Afterwards. Al Romeo remained a state run company until the 1980s, and then it was taken over by Fiat, if I’m not mistaken.

Crew Chief Eric: Ruby, Joanne Wright. Were there any drivers that felt unhappy about Italy’s fascism back then?

Paul Baxa: Great question.

There is no one that comes to mind. I don’t know of any driver that comes to mind that was either anti-fascist. Or in some way bothered by the regime. Not to say that these guys were fascists necessarily. Antonio Skai, I think, belonged to a local fascist cell in Milan, Gaston, really, Perry, whom I mentioned, he’s the one that won the 25 Italian Grand Prix.

I think he was, he had a, he was known to be a, a fascist, actually politically active. Fascist. As for the others, they were, I, I would argue they were neither fascists or [00:31:00] anti-fascists, as far as I know. Again, we don’t know enough. This is a gap in the research. I think we don’t know enough about a lot of these drivers during the fascist era because they didn’t write much.

Uh, n Vladi did write a couple of articles, had it written for him, I don’t know, but his name was attached to them in some of the sporting magazines where he used some fascist language. Enzo Ferrari actually in the newsletters, would write periodically articles that exalted Mussolini’s regime. But you have to remember too, that after the war, there was a lot of post hoc refashioning or sanitizing of a lot of this, and a lot of drivers, and a lot of people who carried over did not really talk much about that past politically Anyway, so we, we, we don’t know enough on that topic, but it’s, it’s a, it’s a great question.

Kip Zeiter: Thank you, Paul. That was terrific.

Paul Baxa: Thank you. Thank you.

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. [00:32:00] Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers. Race series and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, [00:33:00] print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding.

Of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future. For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, [00:34:00] additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 The Alfa Romeo P2: A Racing Legend

- 00:53 The P2’s Broader Significance: Fascism and Motorsport

- 03:00 Historical Context: Italy in the 1920s

- 04:21 The P2’s Racing Achievements

- 05:11 Design and Engineering of the P2

- 06:40 The P2 and Italian Industrial Culture

- 07:34 The P2’s Impact on Italian Motorsport

- 22:11 The P2’s Legacy and Continued Influence

- 26:47 Q&A Session; Closing Remarks and Credits

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

The P2’s dominance culminated in 1925, with wins at Spa, Monza, and the new Autodrome de Montlhéry. At Spa, Alfa lapped the field, prompting jeers from the crowd and tales of panini-fueled pit stops that may or may not have involved a full picnic spread. At Monza, Antonio Ascari’s aggressive driving earned rebukes from race officials – and later, a state funeral when he died in a crash at the French Grand Prix.

Ascari became fascist Italy’s first racing martyr. Mussolini’s wreath bore the words “Repose, the Intrepid,” and the funeral card exalted Ascari’s sacrifice for the fatherland and Italian industry. His death set a template for how fascist Italy would memorialize its fallen drivers – speed and death in service of glory.

While Mussolini didn’t subsidize racing like the Nazis did, he did intervene to save Alfa from bankruptcy. In 1933, the company was taken over by the IRI, Italy’s state-run bailout institution. Though Alfa’s cars were raced by Scuderia Ferrari, the brand was effectively state-owned. By 1938, Alfa Corse returned as an official works team.

Both Italy and Germany used motorsport victories as propaganda. Alfa’s wins were front-page news, just like Mercedes and Auto Union’s triumphs in Nazi Germany. Yet Alfa transitioned smoothly into the postwar era, shedding its fascist associations. Sporting heroes like Ascari and Ferrari retained their popularity, and Alfa’s legacy endured.

Even after Alfa withdrew from Grand Prix racing in 1925, the P2 continued to win under Scuderia Ferrari. Modified versions raced until 1930, including a final victory at the Targa Florio. The car’s design influenced Alfa’s 6C sports cars, which became icons of Italian engineering. Historian Peter Hull noted that Alfa was unique in transferring Grand Prix technology directly to road cars.

By 1930, fascism had reshaped Italy’s political landscape, and Alfa had become Mussolini’s favorite brand. He called it “our best national product” and was often seen behind the wheel of an Alfa. The P2’s legacy was sealed – not just as a race car, but as a symbol of Italy’s industrial ambition and political transformation.

Today, two original P2s survive – one in the Alfa Romeo Museum in Arese, and another in the automobile museum in Turin. Whether they still run is uncertain, but their legacy is undeniable. As historian Paul Baxa reminds us, the P2 was more than a machine. It was a cultural object, a political tool, and a vehicle for Italy’s transformation – on and off the track.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)