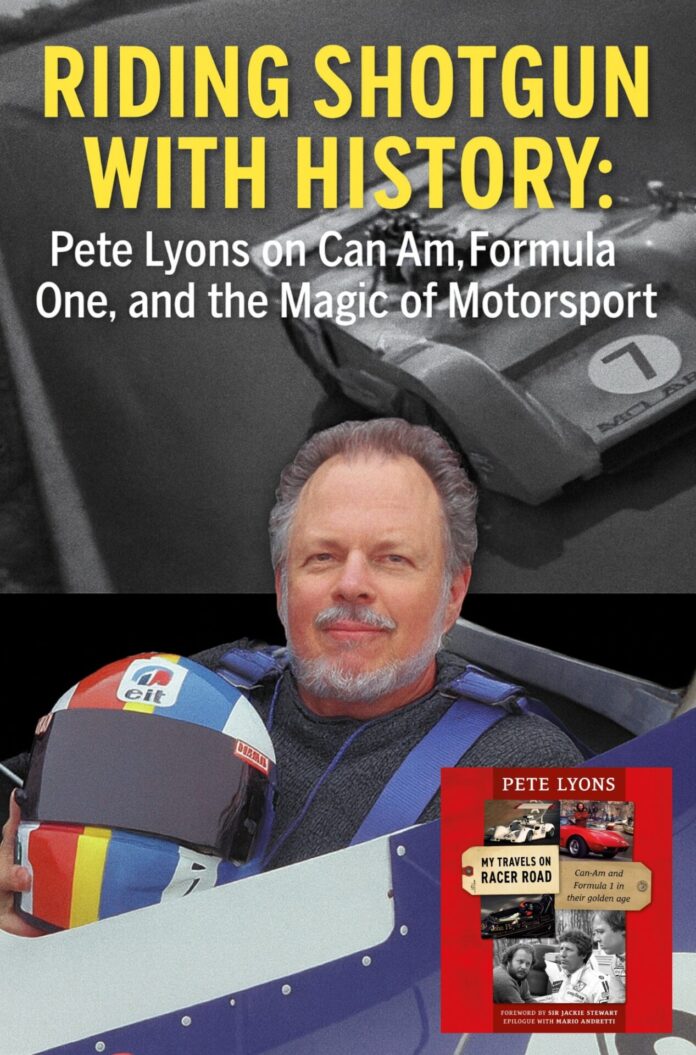

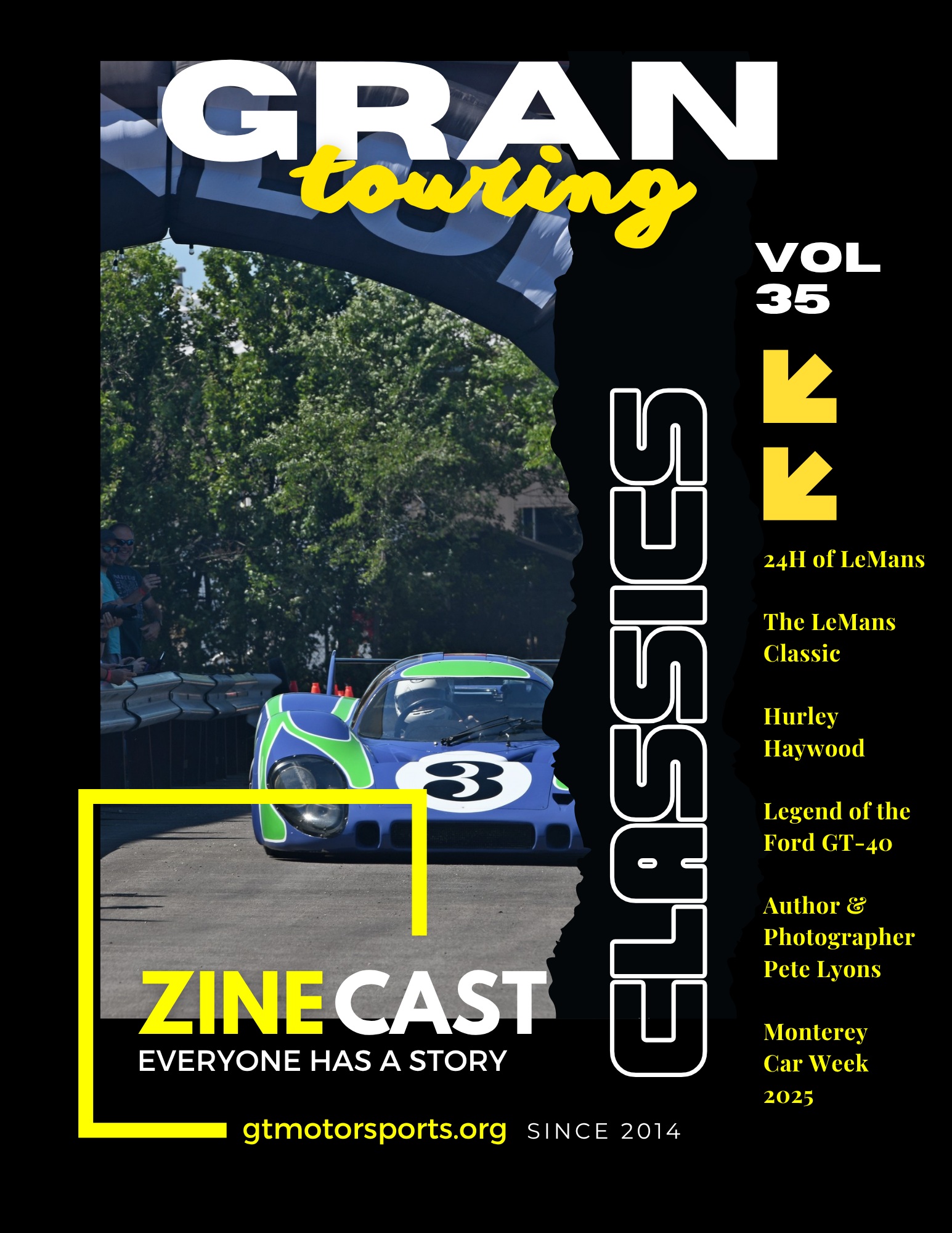

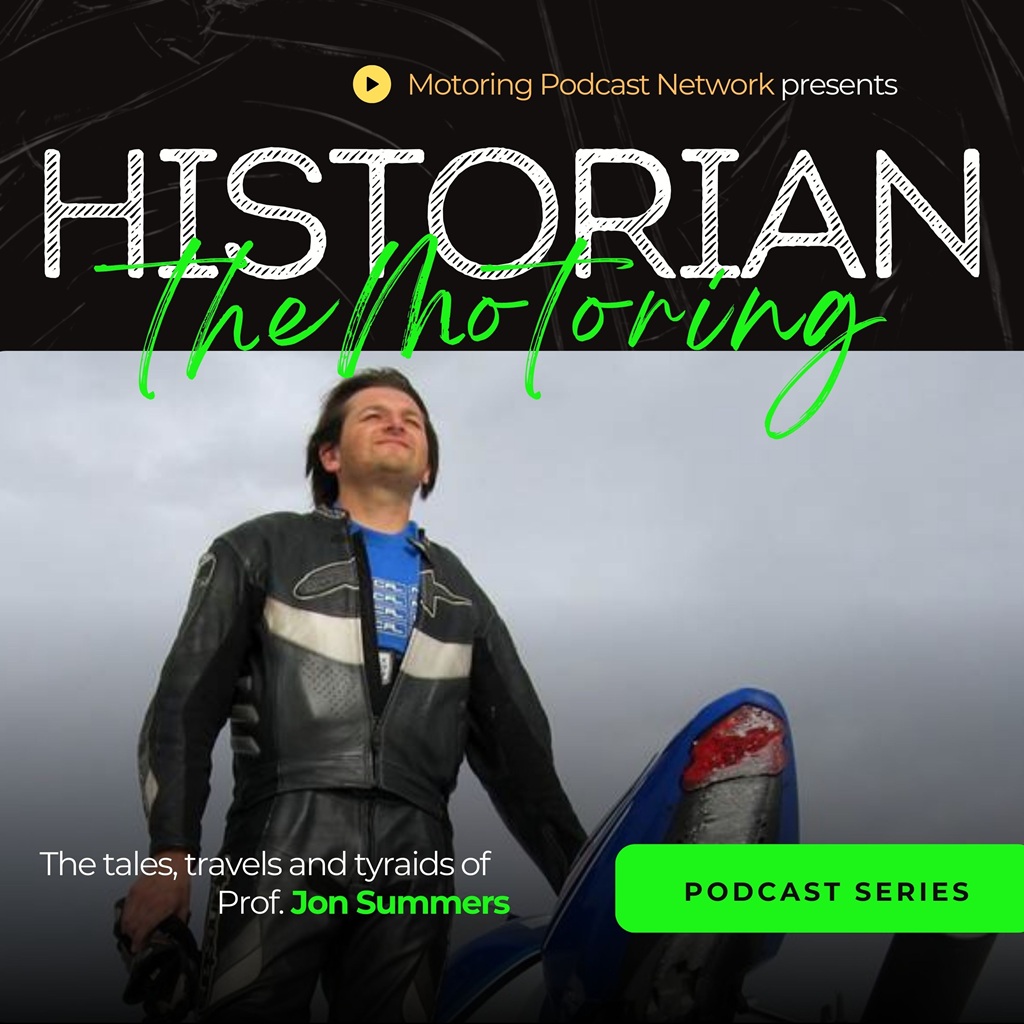

Break/Fix podcast is known for spotlighting the unsung heroes and legendary voices of the automotive world. In this episode, host Crew Chief Eric and The Motoring Historian Jon Summers welcome one of motorsport journalism’s most revered figures: Pete Lyons. With over five decades of storytelling, Pete has chronicled the roar and romance of racing – from the thunder of Can-Am to the elegance of Formula One.

Pete’s journey into motorsports wasn’t love at first sight. As a child tagging along with his father, Ozzie Lyons – a photographer and journalist – Pete found race weekends more about Howard Johnson pit stops than horsepower. But everything changed when he got behind the wheel. Driving unlocked a visceral thrill, and soon he was hooked. With a camera in hand and access to his father’s darkroom, Pete began capturing the sport’s soul through images and words.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

In the early 1960s, Pete set off for Europe with a backpack, a loaf of bread, and a dream. He bought a secondhand Norton motorcycle in London and chased races across the continent – from the Targa Florio in Sicily to the Nürburgring in Germany. His travels weren’t just about sightseeing; they were a pilgrimage to the holy sites of motorsport. The Nürburgring, with its 14.7-mile loop and 180+ corners, became his favorite – a dangerous, devious track that embodied everything he loved about racing.

Spotlight

Born in 1940 in New York State, Pete Lyons is an international motorsports reporter, photographer and award-winning book author in the fields of Formula 1, Can-Am, endurance sports cars, IndyCar, Trans-Am and many more forms of racing. In his decades-long, worldwide career, Lyons covered events on all six populated continents for numerous enthusiast publications, including Autosport, AutoWeek, Car and Driver, Racecar, Road & Track, Vintage Motorsport and many others. He is also the author of 20 published books including, for Evro Publishing, Shadow: The Magnificent Machines of a Man of Mystery, which won ‘Specialist Motoring Book of the Year’ at the 2020 Royal Automobile Club Motoring Book of the Year Awards (UK) and ‘Best Book’ at the 2021 Automotive Heritage Awards (USA).

Synopsis

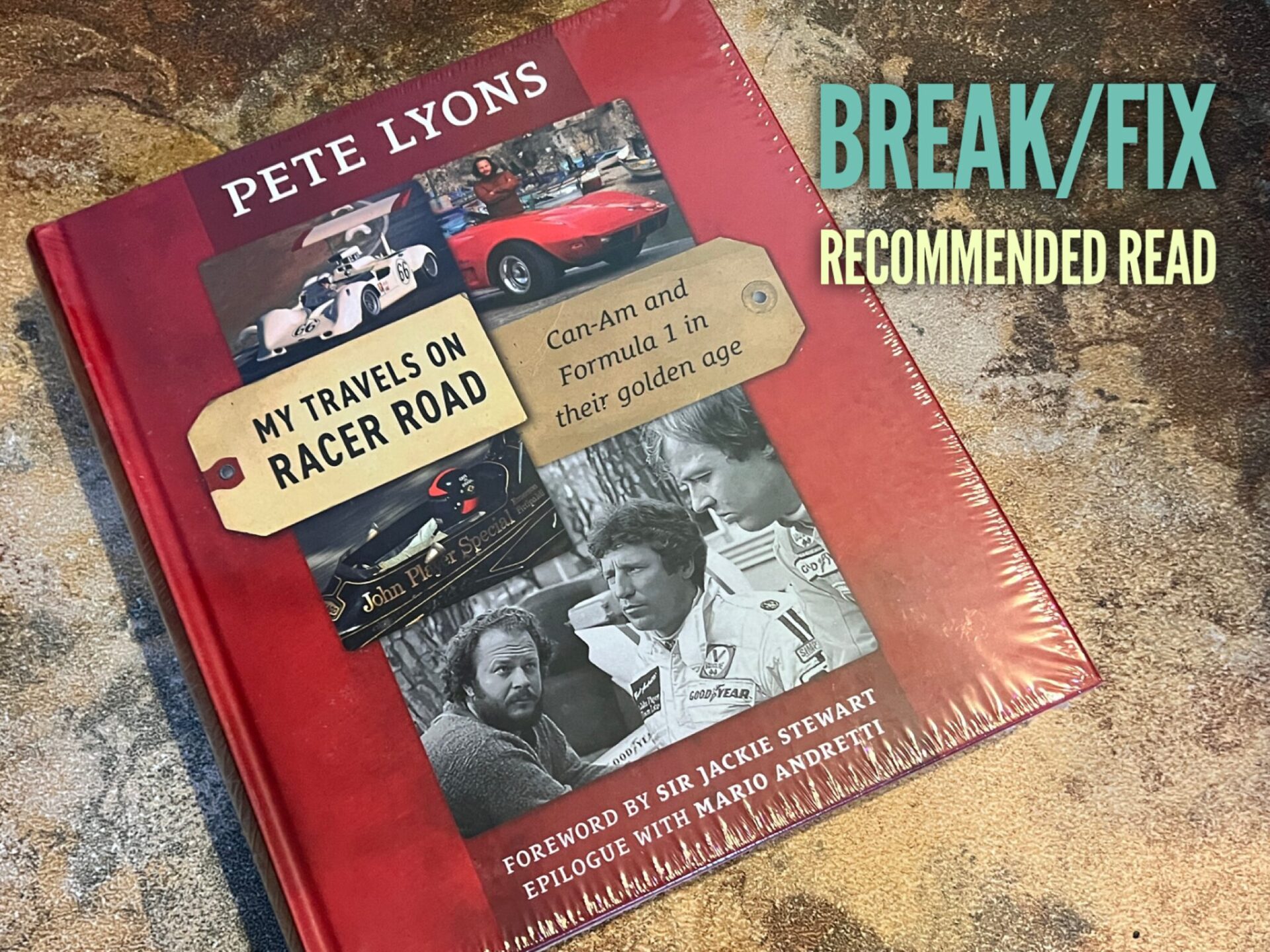

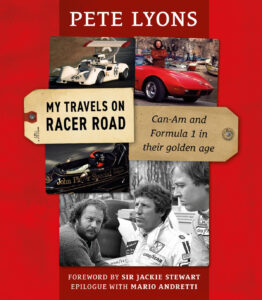

This Break/Fix episode features a conversation with Pete Lyons, a renowned motorsport journalist with a career spanning over five decades. Lyons shares his journey from a disinterested teenager to one of the most respected voices in motorsport journalism. He discusses key experiences, including following his father’s footsteps, backpacking across Europe to attend races, and covering iconic moments in racing history. The episode delves into the golden era of Can-Am racing, the rise of Formula One, and the evolution of motorsport journalism. Lyons also discusses his latest book, ‘My Travels on Racer Road: Can-Am and Formula One in the Golden Age,’ offering insights into his career and the stories behind some of the most memorable races and personalities he has covered.

- And joining us is Jon Summers, the Motoring Historian, one of the many personalities on the Motoring Podcast Network!

- Reading your most recent book it looks like you weren’t that enthusiastic about cars when you were younger. Yet by your teen years it was the passion of a lifetime. What experiences did you have which piqued your interest (and future career)?

- Let’s talk about what first drew you into the world of motorsports journalism, and how did your career get started?

- The perception of Can-Am was no regulations. Was it really like that? Who were the top 3 innovators?

- What were the best tracks for can am? Was it the fast open ones, or were the slower tracks a better spectacle?

- Did teams spying on each other’s cars ? What was the attitude to poking your nose in other team’s garages?

- By the mid seventies you were back in Europe reporting on Formula 1. How did that come about?

- How has motorsports journalism evolved since you started, and what are your thoughts on the digital media era?

- You’ve authored several books—what’s your process like when diving deep into the history of a particular series or figure?

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autos sphere, from wrench, turners, and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of Petrolhead that wonder to. How did they get that job or become that person?

The Road to Success is paved by all of us because everyone has a story.

Crew Chief Eric: Tonight we’re honored to welcome one of Motorsport Journalism’s most respected voices. I. Pete Lyons with a career spanning over five decades. Pete has covered everything from the raw thunder of Can-Am and Formula one to the gritty drama of endurance racing at lama. His vivid storytelling, deep technical insight, and front row access to some of racing’s most iconic moments have made him a staple in publications like Auto Sport Road and Track Auto Week and Vintage Motorsport.

Whether he’s recalling battles between legendary drivers or peeling back the curtain on Motorsports innovation, Pete [00:01:00] brings history to life with unmatched passion and precision, and we’re going to dive into his latest publication. My Travels on Racer Road, Canam and Formula One in their golden Age with a man who not only chronicled Motorsport history but lived it.

Joining me tonight is John Summers, the motoring historian, one of the many personalities on the Motoring Podcast Network. And with that, let’s welcome Pete to break

Pete Lyons: fix. Well, Eric, John, and, and everybody, thank you so much and I’m gonna hire you to be my publicist. You did a great job there. It really is.

Jon Summers: Marvelous, isn’t it?

Pete Lyons: Some of it’s

Crew Chief Eric: almost true. It’s all true. Even the lies. Pete, with that said, reading your most recent book, it looks like you weren’t that enthusiastic about cars when you were younger, but yet by your teenage years, it became a passion of a lifetime. So what were the experiences that had piqued your interest and set you on the path for your future career?

Pete Lyons: My dad was really keen on cars. Ozzie Lyons, photographer, engineer, movie guy. He did a lot of things, but he was a, a journalist, did a lot of photography at car races and so he was really very [00:02:00] interested in cars, especially car racing when I was like 12 years old or so, I would go along with him to the track, like a family vacation.

We go from New York state all the way down to Florida to Seabring every March, so dad could photograph the races and we could play in the sand and the mangrove swamps and so on. But I was completely bored by cars. I mean, I’m in the backseat. I’m a kid, I don’t get to do anything but sit there and wait for us to get to the next Howard Johnson so we could have some lunch or something.

And so I had no hands on experience of a car, so I didn’t understand what it was all about. But then when I got to learner’s permit age, dad started teaching me to drive. Oh, I get it. This is fun. In the matter of weeks, I was a converted race car person. I remember vividly my first time had driving a car and also being in at a race where I was interested and Dad gave me a camera and told me about shooting, and then he had a dark room at home.

Every house we lived in in, he built a dark Aram. So I got hands on instruction on Souping [00:03:00] film and making prints and so on. Basically, that’s the path that set me on and here I am.

Crew Chief Eric: So as we continue down your journey, looking through the chapters of the book, it seems like you were a backpacker before backpacking was popular, and you hear those romantic stories about a loaf of bread and a bottle of wine and traveling through Europe.

So you found yourself in England and then continuing on European travel. What drove you to go to Europe?

Pete Lyons: Well, let me first say that there were a lot of backpackers in my day. It’s not a new phenomenon. We’re talking 19 61, 62, 63. When I was there. I was with backpackers all the time. There’d be two or three standing at the side of the road when you’d walk up and stick your thumb out or on trains or sleeping in campsites or on park benches in Paris.

True story. I did that. So, you know, backpacking was not novel, but it’s a way to go.

Crew Chief Eric: So was it motor sport that drew you to Europe?

Pete Lyons: Oh yes. Yeah. I was not doing much of anything by the time I turned 20 years old. A whole bunch of stories in the, in the book about what I was doing, [00:04:00] traveling and working and so on.

But I was really trying to go to all the races I could and I decided I have to go to Europe and so I went to Europe. I had enough money for about two months in Europe. And then at the end of that two months, I didn’t want to come home. So I found a job and I worked that winter and then I traveled the next summer and worked again that next winter and traveled some more the third year and I just didn’t want to come home.

I went to as many races as I could. I bought an old Norton motorcycle secondhand, and I traveled all the way down to Sicily, to the Target Florio. In 1962, I went to the Berg Ring in Germany where I froze the piston and the cylinder. It was a single cylinder engine and I devoured the piston and had to wait in Germany for nine months before I could fix the bike.

I learned a little German then.

Jon Summers: What Model Norton was it?

Pete Lyons: It was a 1959 model. 50. It was a three 50 single, very basic, but the engine wasn’t anything special. What I liked about it was what I’d read about the road holder forks and the featherbed frame. You know, the man won so many motorcycle races in [00:05:00] that era.

I. And this was basically the same motorcycle. A lot heavier, a lot slower, a lot cheaper, but so am I. So it suited me fine. I, I enjoyed riding that all over Europe. Where did you buy it? In London. I bought it, I walked into a dealer in London and you showed me the bike and I bought it.

Jon Summers: It was the new bike, was it?

Pete Lyons: No, no, no, no. Two years old. This, this was almost winter time of 61 when I bought it. And it was a 59, so it was two years old. It was a good bike, but I did thanks to it that I shouldn’t have.

Crew Chief Eric: So you’re deepening your romance, your love affair with Motorsport being in Europe, because every time you turn around there’s a famous racetrack here, there and everywhere.

Had you established, at this point, maybe some favorites or some bucket list tracks that you were trying to get to, to record a photograph or capture or just experience?

Pete Lyons: Yes, but the first one on top of the list is always going to be the Burging, that Fantastic Mountain Road course in eastern Germany. In those days, it was 14.7 miles around and it had something like 184 corners depending on how [00:06:00] we count a corner.

And it was incredibly difficult to learn. It was incredibly devious. It was really damned dangerous. It’s my idea of what a racetrack ought to be, and I know it. Doesn’t fit into the modern, uh, conception of what racing ought to be. So be it. I’m in the old days.

Crew Chief Eric: Compare that to Lama.

Pete Lyons: Lama is totally different.

There’s a lot of magic there. It’s not as long. In those days, it was about nine miles around far fewer turns. The driving isn’t as intricate. But of course you do it for 24 hours and there’s two to three, even sometimes four different people in the car. So each one wants something different. So you have to compromise.

And also in those days it was really endurance cars could not stand flat out driving for 24 hours like they can today. It’s astounding what they can do today. But you, you had to nurse the car. I’ve been at Lama late in the afternoon and on Sunday afternoon they’re, they’ve been running like 23 hours and they just have to get through the last hour.

The engine note that used to be so pure and clean and lovely in the middle of the [00:07:00] night. It’s sounding hoarse and raspy and something’s gonna break if I’m not really careful. The cars are streaked with filth. I mean, they have been through a long, long endurance, you know, 3000 probably miles, uh, in the 24 hours.

So it, it’s a totally different experience and perfectly valid. Is that. And I love night racing. I love watching the car has emerged from the darkness and flash by and you see the flames from the exhaust and the bright red brake rotors and so on. So it’s a spectacle, but it’s not like Formula One at the Berg Brain.

For instance,

Jon Summers: your story at the beginning of your book that’s just coming out. The story of seeing the mat coming by at Lamar, it really resonated for me. Thank you. My best memory of Lamar, I went three years in the Audi years, about 20 years ago, and my best memory of Lamar is having the ritual Chinese meal at the restaurant at Herand Air, which I only did that once.

And then walking down, and it would’ve been like 2000 or 2001, the guys I [00:08:00] were wi was with were like, you know, za Straits just there. We could like walk down this driveway and like into this guy’s back garden. And so we got close to the, and I remember the, I remember the night of the Corvettes and the glowing break discs.

Yes, your piece. Brought that alive for me again. Ah, thank you. Thank you. It was magic.

Pete Lyons: It was magic being there and I, I always figured my role was to try to express the magic for what I felt for people who couldn’t be there, but wish they would.

Crew Chief Eric: So that’s the perfect segue into our next portion of your story, which is when did the light switch flip and you went from backpacker and motorsport, enthusiast to motorsports journalist.

What were the series of steps that brought you to that point and then realizing that that was gonna be your career?

Pete Lyons: That overstates the case. It just sort of happened and it happened because my dad was already associated with Autosport, the English weekly. You know, Motorsports publication from London.

Dad was their USA correspondent and photographer for some years. And so it was actually not a path [00:09:00] I chose, it was the path dad was following as on a weekend. And so I’m going along with him and I remember the thrill I had the first time, bought a sport, published one of my own photos. I mean, this is so exciting and I have to tell you, it’s still exciting, but I couldn’t figure out the, I was not aware of anything else I got to be doing.

I thought I should do this. So I did.

Jon Summers: I wondered if. Part of the reason why you came here in the first place wasn’t Dennis Jenkinson’s Continental Notes. You’re exactly right. As a mobile sports subscriber myself, that lifestyle was appealing to me, and I wondered if the Norton bike and the coming to Europe and the following, the Continental circus was DSJ instrumental in that.

I got the sense he was

Pete Lyons: absolutely. I often call Jens my guru. I never said that to his face, but when I was still in high school, someone gave me a book for Christmas. Obviously my dad, it was Dennis Jenkinson’s book called The Racing Driver, which I still have, and I’ve photographed. There’s a picture from it in the book.

[00:10:00] Jinx had this life, and it was the Continental Notes you could read sometimes in the magazine. We didn’t get that magazine, but I saw copies from time to time. So I knew this English guy. In those days, he had a Porsche, a little 3 56 coop, and he would motor around Europe going to these fantastic races like the Targa, Florio like spa, like Monaco, Rimini, Pescara, places like that.

And then he would write about his journeys and then his stories about the races. They just spoke to me. He brought out the feeling in me. I can remember there, there was a, a story that Jenks wrote. I think it was about Pedro Rodriguez driving a Porsche nine 17 around brands Hatch and probably the BOAC six hour race, something like that.

As I recall, it was a rainy day and he just described Pedro just dancing slithering around that wet. Racetrack. And honestly, John, I felt my breath coming fast. I was, and I’m sitting 3000 miles away months later reading words and I, [00:11:00] this is powerful stuff.

Jon Summers: Yeah, it’s, it is awesome. That reading your words in the book, expressing that for me, the article that did that for me was Dan Jenkinson’s article about the Milli Milia in 1955.

It was republished in 1995. In the June edition of Motorsport, and it was right after I’d finished graduation so I could read something that wasn’t the decline and fall of the Roman Empire for a minute.

Pete Lyons: Yes,

Jon Summers: and I read the Jenkinson article and I loved it. Yes. Love the sense of. Adventure and there’s a sense of joy diviv, which is missing from contemporary motorsport, and it’s sad that that’s gone.

Pete Lyons: I’m not close enough to motorsport to be sure, but I think the people who are involved in current motorsport, I think they’re as passionate about it as we were in those days. So I’m not gonna say that they’re not finding the same kind of enjoyment. It’s different from what I remember. But on the other hand, there’s a lot of it.

It’s [00:12:00] good too. For one thing. We’re not killing as many people.

Jon Summers: That was the perfect segue into talking about the mortality.

Pete Lyons: I don’t think we want to dwell on it. I think people know that it was very dangerous. I mean, all you had to do is look at the cars and the circuits and the driver’s suits and so on and and the helmets.

And they were very aware that it was dangerous. There were ongoing efforts to make it safer. Every year they tried their best to improve the cars and improve the barriers and et cetera, et cetera, but we kept losing people. The first year in my, in Formula one for me, we lost two drivers and then the next year we lost one, and the third year we lost two more in 76.

My last year, I don’t think anyone died. I not on in Formula one that I can remember. I might be wrong, but it was a very, very dangerous period. I put this in the book, the editor of Autosport in those days, he was the founder. He was a Scottish guy named Gregor Grant, and he said something once, I think he wrote it in one of his editorials.

He said that, you know, motor [00:13:00] racing is indeed dangerous, but you know, you must remember that when we started in the late forties, early fifties, we had just come through the most dreadful war and we were used to horrible things happening. And so motor racing is quite innocuous by comparison. So that was their thought.

Nowadays we have moved so far beyond that, we just don’t know what it was like then. And nowadays when someone is. Killed. And it does happen. Many younger people are just shocked. How can this possibly happen? And yet it was part of the game back in those

Jon Summers: days, very much so. And I, I feel like that kind of motorsports survives in the form of the Isle of Man tt Yes.

Have a place of students at local university. And for them, they see the TT more as existing with other extreme sports than it does with Motorsport, as the resident motorsport as they understand it now. And I thought that was quite an interesting perspective.

Pete Lyons: It was something that we had to deal with. I had to write obituaries for [00:14:00] people that I thought of as friends.

I used to try very hard not to get close to them because there was that risk of, you know, losing them. I wasn’t very good at not being friendly with ’em because they’re such fascinating people. I’ve said before that I don’t recall ever meeting someone in motor racing who wasn’t an interesting person in one way or another.

Part of it is we’re all there because we’re all enthused by the same thing, and you just feel like you’re part of a fraternity. I’m on the outskirts. I’m a journalist. There’s an adversarial relationship that one is aware of subliminally. It’s not that they were unkind to me or wary of me, but you could see that the way the mechanics talk to each other is a little different than the way they talk to the journalists who stopped by.

I developed good friendships and, and they would tell me things that I heard them not telling other people, you know, you never actually break through the barrier and get to the inside. I discovered that a couple times when I joined the crew of a, a race team on a, like a club racing thing. All of a sudden I’m a remember a team and [00:15:00] somebody else comes around and wants to know what we’ve done and.

I can feel it. I’m not going to tell him. I can see from that perspective how my approaching any of the mechanics or, or designers or crew chiefs around the racing team in those days, they would be cordial and friendly and partly because I’m the press and so they want to be nice to you so they will write about them and so on.

So it’s a, it’s a lovely conversation. In the same moment you can see in their eyes, I’d best be careful. He might ask me something I shunt wish to tell him. You know,

Crew Chief Eric: let’s switch gears and talk about Canam. We have had only very few opportunities to discuss Canam on this show. I had been fortunate to sit down with a friend of yours.

We had Rick Nup on here. Yes, talk to us about his Lamont experience. But he has tons of racing experience in Can-Am and he shared those stories with us. And so I want John to lead us down this exploration of Can-Am. It has such a mystique around it and has such an epic period in Motorsport history. So, John, take us down this road [00:16:00] with Pete

Jon Summers: really does have a epic kind of, uh, worldly feel for me as a, as an Englishman.

So let’s begin with the obvious about. Canam. The perception is that there were no regulations. It was this sort of wild west of no rules.

Pete Lyons: Was it really like that? There were some rules, but there were so few rules. Many people have said, I like to say it was the thinnest rule book in Motorsport. It probably rivaled only by the Pikes Peak Hill Climb Rules where it says Open class at Pikes Peak.

Is any car capable of going for the Hill Climb Track record is eligible. Okay, we can work on that. Canam did have rules because it was associated with the Sports Car Club of America and their Canadian counterpart, CASC. They came together and they produced a sports car series, an international one between the two countries.

That’s why it was called Can am Canadian American, and it was a series of professional races. Across North [00:17:00] America and they adopted the old idea of sports cars as experimental things Can-Am cars didn’t come into being. They evolved outta what had existed before. In Britain, you had what they called big banger racing.

They were McLaren’s and Lolas and other cars. British made chassis with big Chevrolet Ford and Oldsmobile engines. They were called big bangers, and the crowds loved them. And I’m talking, you know, 64, 65, and we had the same thing going on in the States. Not only English cars with American engines, but we had American cars like the Cunninghams came before them.

Then we had the scabs in the late fifties, and then by the early 1960s, they were building things like the Chaparral 63, 4, something like that. Again, all of that was. A fermenting growing blossoming thing, which in 1966 was codified in the Can-Am. But that whole ethos of you wanna put a bigger [00:18:00] engine in it, oh, that’s great, let’s hear it run.

Whereas eventually, and in most cases. Rules get piled on top of rules. One rule leads to two more and eventually you can’t move. If you wanted to design a Formula one car or a Lama car today, but you wanted to make it a little wider than usual, Uhuh can’t do that. Lad, you wanted to make the engine a little bigger.

Uhuh not allowed. Seems like every line of a modern design race car is drawn for the designer by some rule or another. It’s so constrained, whereas Can-Am was wild and free. You want a bigger engine this year or this week? You want a bigger engine. Okay? We’d love to see that. You want a different transmission.

You want to make different aerodynamics. Remember, the Chaparral came up with that wing on the above, the rear wheels so that it would, aerodynamics would push the back wheels down on the road. That was unheard of and yet was perfectly legal in Canam. Everybody loved it so that it was a totally different era.[00:19:00]

Jon Summers: So thinking about those kind of creative innovations, I mean, you mentioned Jim Hall and Chaparral. Who would you say the top three innovators were in Canam?

Pete Lyons: Chaparral with Jim Hall and Hap Sharp for sure. They did the first fiberglass, meaning composite chassis in racing in 19 63, 62. There had been a car made by Colin Chapman at Lotus, which had a glass fiber chassis, but that was a road car.

The elite Jim Hall, I’m sure he knew about that car, but they built a rear engine sports car that had that fiberglass chassis. Guess what? Today everybody has a carbon composite chassis. So that was an innovation which has stuck. Jim Hall pioneered what everybody called an automatic transmission. It wasn’t automatic.

It was a torque converter transmission. So in other words, there was no clutch, but you put your foot on the gas pedal and the thing locked up in the car moved forward. And the way you changed gear was you simply moved a lever. You had to [00:20:00] move the lever. It didn’t do it by itself, so it wasn’t automatic, but it was an innovative, different kind of transmission that allowed the driver to have two pedal control, just like you have in a Google cart.

Left foot brake, right foot gas, and like you have in Formula One cars and other cars today. Again, that that was a Chaparral thing that came about in the early 1960s. And then the aerodynamic revolutions that Jim Hall came out with, I described the wing, and later on there was the fan car that had an extra motor.

You could add an extra motor to a KN car. Nobody said you couldn’t do it. And that was to spin a couple of fans at the back, which extracted air from out under the car and turned the whole car into a limpet, you know, suction cup. It just grabbed the road. Those are the main things that Chaperral did. They also were the first people that I was aware of doing instrumented testing.

I have a picture that I took at Bridge Hamden once, a big passenger seat of the Chaparral with a big reel to reel tape recorder sitting in the passenger seat, belted in with wires, going to all sorts of sensors [00:21:00] around the car, and I knew enough not to ask, what’s all that for Mr. Hall? Oh, would rather not talk about that.

I asked Jim Hall once there had been a little aerodynamic appendage at the nose of one of the chaparrals, like a little additional aerofoil, no, no bigger than my arm, stuck at the front where the air intake was. Then it disappeared, and I, I said, Jim, why? Why did you, why have you removed that little appendage that front of the car while Pete.

I had enough time to think I’m gonna get a great answer here. He’s thinking about his answer. It had a neurodynamic effect that I’m not gonna tell you about. Thank you, Mr. Haler. This is the kind of thing that made that whole episode of my life so much fun. I felt like I was in a giant adventure going along with people who were opening doors into the future and they tolerated me tagging along and watching them and taking pictures and writing about it.

I wasn’t one of them, but they welcomed me to come along [00:22:00] on the ride. It was just so much fun.

Jon Summers: I was lucky enough to meet Don Nichols some years ago, and I found talking with him in the pit lane at Monterey. He clearly relished telling stories, and I found myself thinking some of these are true. Some of them I’m not really sure about.

I’m just enjoying all of them. Talk about some of the innovations that you remember shadow bringing to Can-Am.

Pete Lyons: Well, the first one of course was Trevor Harris’s tiny tire car, the 1970 car. Trevor and Don got together. Trevor had fountains of ideas. He’s an amazingly talented, brilliant, innovative guy. His mind just throws out ideas like sparklers.

He wanted to try a car that was like a go-kart and that had small wheels. He had, he wanted 10 inch diameter wheels, so therefore like 14 inch, 15 inch diameter tires and slightly larger at the back. But the whole idea was to make a car that was lower to the ground. Trevor knew about endurance carts.

Doesn’t say that. That’s what led him [00:23:00] to the idea, but the same concept, getting a smaller package down low. And so there’s less air resistance. And he thought with a, a smaller engine but less air resistance and less weight, you could go as fast as a big block heavy car. And so he got done. Nichols interested in that, and Don agreed to finance it.

And so they came out in 1970 with this most. Amazing thing. I mean, it would literally stop you in their tracks the first time you saw it, thought for the first time at must sport in 1970, I knew what it was, but I hadn’t seen it before. And good Lord, so how can I photograph this? You know? So get down to my knees, and I looked photographed up because that would elevate the height of the people around it and things like that.

It was not a successful car. A lot of that had to do with circumstances outside of Trevor’s control, but it led to a long line of other shadows, each of which got more and more conventional, but finally won the Canam Championship four years later. So that’s an important car. And then in Formula One, they did [00:24:00] do some cars that were fast, particularly in 1975.

The Shadow DN five was it. That started from pole position on a couple of races that year, which is darn good in Formula One. In 76 I think they won a race. They won the Austrian Grand Prix. Alan Jones, later a Formula One champion won his first Grand Prix with shadow at the Austrian Grand Prix in 1978.

So, but then the team never had the funding it needed, not when they started to get good, so it faded away. The story is fascinating. Don Nichols own personal story is fascinating. Trevor Harris and Peter Bryant, who was an interim designer, and then Tony Southgate who did the successful cars later, what a kaleidoscope of fascinating people.

Jon Summers: Absolutely. That’s what I found myself thinking that Don Nichols was in his seventies when I met him. He had a long ponytail and I was like. Dude, that’s just so cool. Riding with Revy. Ah, you must have been [00:25:00] friends with him for that all to come along and just explain to people who’ve not perused your book, what that’s all about.

Pete Lyons: Riverside Raceway 1971, a few days before the very last Canam of that year, and at the end of that race in 1971, Revson was going to be the first American to be the Can-Am champion in McLaren MAF. You can see the two seats in there and the full Bo that you work over the wheels and it actually has doors here on each side.

And those three things together make it a sports car. Other than that, it’s a, it’s a wild, basically unlimited car. The engine was as big box Chevy as they could make with an aluminum block. Gearbox was big and, and they could absorb that torque. The tires were big and fat. It had aerodynamics on it. By this time, there were some rules restricting The aerodynamics could no longer have them mounted up in the air like Chaparral had with struts going down to the wheels to press the wheels themselves down onto the road.

This way, the downforce goes through the body and the suspension down to [00:26:00] the wheels, which isn’t as pure as the Chaparral, but that got banned. So more and more rules were creeping into the cannon. Anyway, to your question, it was a, I think it was Tuesday before the race and one of the sponsors had some of their people out, and I was out there anyway because I’m a racetrack junkie.

Hey, they’re gonna be testing today, I’m going out. And I found that, uh, ready was giving people rides from the sponsor. So I got in line and they looked at me, oh, I paint in the seat on this side. There was no upholstery in it. It’s nothing but a sheet metal tub, you know, aluminum tub. Although the rules said that it was supposed to be equal for the driver and the passenger, they did cheat it over a little bit because there wasn’t enough room between the fuel tanks for two human beings.

So the driver needed to have a good seat and the passenger only needed to be along. He didn’t have to actually be comfortable. I can, I remember sort of driving my hips down into this narrow thing. And then I had to keep my right arm away from Revson. He’s right hand [00:27:00] drive car, and he’s shifting with his left, doing this with his steering wheel.

And so I didn’t want to get into his way when he’s steering the car. Teddy May, the team manager, he clasped by hand. He was doing this to everybody. He said, give your hand. He held it up and clamped onto the roll bar here, where, where my thumb is, that sloped part of it. And, and that’s my head underneath there.

And so I’m holding on like this. And on the left side, I’ve got my hands out as far as I can and holding it over the outside of the mono clock underneath the door. And then my foot well, was so narrow. The only way I could get in there was to take off my shoes and in my stocking feet, I put one over the other and just sort of slipped in there.

So it was not what you call a, a relaxing and comfortable position, but. At a time like this, who goes for comfort? We went out of the pit. By that time I knew Riverside, I’d done a Formula Ford School there. So I, I was familiar with going around Riverside at Formula Ford speeds. But this thing was, he sort of motored out of the pits and then nailed it in first gear and literally my head went like that.[00:28:00]

I mean, you know, we hear about next snapping acceleration. It’s true and nothing but blue sky. Then you put your head down and then bang again. And even when he went from fourth gear in into fifth at 140 miles an hour, whatever it was, there was the same thing. It didn’t lessen with the speed. And I reckon we, by watching the tachometer, which I could see in the wiggling needle, the highest number I saw was the equivalent.

I found out later from the lap chart, from the gearing chart, it was 185 miles an hour. And then after that, he still had his foot down on the throttle for a couple of seconds. So I’m convinced I saw like 190 miles an hour down the back, straight at Riverside with like that. And at the end of it, there’s this boilerplate steel wall around the outside to turn nine.

It’s a long way away, but it’s coming at me like this. And, uh, kept thinking, Mr. Revson, sir, perhaps you might want to think about putting your foot on the brakes, sir. I’m exaggerating. But when he did, I [00:29:00] saw why he didn’t have to do it before. I mean, we just like that. And if I had not been holding onto the bar like this, I have a feeling I would’ve pivoted outta the car, forward my ankles over my heels, out over the nose of the car.

That was the feeling I had. I’m glad Teddy put my hand here.

Jon Summers: You mentioned Teddy Mayer there. Yes. In the wake of Bruce McLaren’s passing, did Teddy hold the team together? I mean, it’s astonishing that the team leader passes and then all of a sudden you have this incredible success in Can-Am and then through the seventies.

Building success in Formula One into the Ron Dennis era. So did you perceive that firsthand? Talk about that

Pete Lyons: Teddy Mayer for sure. I mean, he was a very early friend of Bruce. He was a business partner. He was a manager financial guy I think. And Teddy was an instrumental portion of the structure that makes a team a part of the machine.

But the mechanics, they were all on board with this keeping [00:30:00] Bruce’s legacy going. Tyler Alexander, another American, both Teddy and Tyler were Americans there. There were a whole bunch of Kiwis, some English, there might’ve been other nationalities, I’m not sure. But it was the kind of team that was so successful and so solid that people wanted to come and work for McLaren.

They brought Dan Gurney and when Bruce was killed 10 days before the first race of 1970, they tapped Dan Gurney to come in and drive the car for the first couple of races. And of course he won the race, both of those races, and then he’d step back. So all of those people, including Denny Hall. Denny home was often described as sort of a tower of strength.

I’ve used that phrase that held the team together, but it wasn’t any one person. But certainly all the people we’ve mentioned, it’s just the way they were. They’re racers, and if you are a racer, you keep racing. If you decide you don’t wanna race anymore, you stop racing. I mean, it’s actually a fork in the road.

Jon Summers: Thinking about the tracks, you mentioned Moss Port. Was canam better to watch when the circuit was really fast, or was Canam better [00:31:00] when it was a slower circuit and it slowed the cars down and they couldn’t use all that power?

Pete Lyons: Each circuit tends to be different, which means you see different things. I wouldn’t say one is better than the other.

Mosport is a wonderful track, still is today swooping and fast and bumpy and varied. You know, I love tracks with hills on them. For that reason. I used to love San Jave in Canada, in in Quebec. Province we go is like that. Watkins Glen has a lot of that road. Atlanta and mid Ohio and so on. Riverside was wider and faster, more open, and longer straits gets the same number of corners roughly.

I used to think of that as a faster track than Laguna second, but then I think it was Denny Holm one day who corrected me. He says, no, Laguna second is bloody fast, Mike. I think it has to do with, even though you’re not going that speed, you’re in a tighter turn and there’s things closer to you, so it still feels that fast.

Jon Summers: It might be a little like Silverstone in Silverstone in its original form. Yes. None of the straits were that long, [00:32:00] but you didn’t have to slow down for any of the corners that much. So the overall lap speed was not that far off. Monza?

Pete Lyons: Yes, Silverstone is a track I’ve known for a lot of years, various iterations of it.

It was built on an airfield, a World War II bomber base, and so it’s basically on flat terrain, so it doesn’t have that dramatic up and down that I love. And you’re right, in those days it had, it was the perimeter road around the runways. It went around the X shaped runways. So it wasn’t that complex a circuit, but it was fast and wide open and wood coat turn in those days, the last turn on the lap.

Was a blood accordingly, fast, right-Hander, I mean fifth gear, practically flat. Practically flat and fifth gear. And on those tires in the seventies with the big baggy Goodyear tires, their bias play tires were not radial. So they, they were floppy springs were soft and the aerodynamics were not very strong in those days.

So you could really see something going on. The cars would lean and [00:33:00] slide and the drivers are working like this and there, there’s two of them doing that. And through boot coat it, who knows? 160 miles an hour maybe that was a vision. And then of course they put in the bloody chicane that ruined it.

Jon Summers: Didn’t shechter one year cause a big pile up or, so I’ve probably denigrated Shechter name unjustifiably there, but there was a big rack. One year and that’s what made them put the chicane in.

Pete Lyons: Shechter did have a big crash there and I guess it was not immediately after, but after that they did put in a chicane.

That’s right.

Jon Summers: Yeah.

Pete Lyons: Later did what everyone called the Shechter chicane at Watkins Glen. Watkins Glen had a somewhat similar sequence, uh, as you know, the glen sort of down and first in those days it was the first turn, sort of fast downhill right up the hill over the crest and so on, and there was a nasty fatal accident that crested that hill once.

Subsequently Shechter lobbied people to introduce a chicane partway through it to slow the cars down. And immediately there were all sorts of accidents at the Shechter [00:34:00] chicane. So they took it out and went back to the original. That’s Jodi’s, uh, contribution to this particular discussion.

Jon Summers: Silverstone used to be my local circuit, so the first time I ever watched a motor race was in the grandstands at Woodcote.

Oh, great. Fully, I appreciate what you mean. It wasn’t until I came to California and I rode motorcycles around Laguna and Infineon see’s point that I realized what they talk about when they say technical because no circuit in Britain is remotely technical. All the corners, they’re just like there. And how big are your cahones?

And you turn in and maybe the car slides and maybe it doesn’t and you wrestle it round. And Silverstone was wonderful for that. Do you have a favorite British Club circuit?

Pete Lyons: Well, I didn’t see enough of them to actually judge that. I liked Brand’s Hatch. In the old days, the first racing car I ever drove was at Brand’s Hatch.

I fronted up one day in 1967, I think, and I paid X pounds and I got four laps and a little formula Junior or something. And it was all over so fast. I can’t really tell you what I thought about it was, oh, this [00:35:00] is, I’m closer to the road than I thought. Oh, those are wheels there. My gosh, this thing just Agile.

Oh, you know, oh, is that the last lap? You know, it wasn’t until I took the formula of the Ford School, then I had three days of it, then another three days of the racetrack. Then I began getting an acclimated to it and I felt, I knew what a Formula car should feel like then. But I liked Brand’s Hatch. I had a wonderful ride with Ronnie Peterson once he was out there testing one of the Lotus Formula one cars, and of course testing his little while of intense action on the track, and then an hour between times while the mechanics changed something.

And so he had a Lotus that was the mid-engine car with a rental engine. So we’re, we’re sitting in the B. He’s sitting there. And the thing about Ronnie is he was so langy. I mean, he was tall, Swedish guy, pale blonde hair, very placid. And in that car, he was sitting back and his left hand was just sort of lying on the console, massaging the gear lever.

And his right hand was on the steering wheel and it was going [00:36:00] like this, and his face was perfectly placid. And at Bren’s Hatch, you came past the pits and went uphill over the crest of a hill, which then went down into a gully. The S speed motor was about 80, and the thing is healed over and sliding and Ronnie’s doing this, it felt like we were in streetcar.

You know, it was pretty hairy. And all this while Ronnie’s driving this and he’s got his head turning me, he’s talking to me the whole time. And I thought I couldn’t do that. I liked Brian’s aelant, but, but you don’t consider that a technical circuit?

Jon Summers: I dunno. Brands. I know Thruxton pretty well and Thruxton is my favorite of the British Club circuits.

Crew Chief Eric: It seems like every adventure we go on with Pete, we can’t stop talking about Formula One in some capacity or your return to Europe after the advent of Can-Am and finishing up that series. So let’s talk about returning to Europe in more detail and your time with Formula One. How did that come to be?

How did you pick up that gig?

Pete Lyons: The short story is that Leon Mandel at Autoweek informed me that I was coming to work for him. Canam was [00:37:00] dying at the end of 72. There were several reasons for it. Not at the only reason, but part of it was, you know, the Porsches had come in with factory cars. The Canna McLaren’s, for instance, had roughly 750 horsepower if you could believe what people told you.

Whereas the Porsches came in at like 980 and very quickly were at 1100 horsepower. I mean, there’s just no way McLaren could compete with that. They would’ve had to build a whole new car, go through a whole new development program. They did a turbocharged Chevy engine, but they were breaking the gear boxes, so they’d have to go through a whole gearbox program.

So at the end of 72, they were beaten by Porsche. They just decided they couldn’t come back. It was a financial thing. It was business matter. You know, you can’t squander money. And at the end of that year, I could see that coming. Lola was gone, Chaperral was gone. Shadow hadn’t yet amounted to anything. So it was just a matter of Porsche, Porsche, Porsche, and I was losing interest and I.

Just one make racing per se. And so I was thinking of doing something [00:38:00] else. Anything else? I didn’t know what I would do, but I was thinking, I, I think this is my last year, I’m gonna quit. And I was walking into the pit lane on the first day of practice and there’s, uh, race cars and they’re running and it’s hard to hear anything but Leon Mandels at the far side of all four of them, they’re two McLaren and two forces.

But Leon had the kind of voice that pierced that cacophony, and he said, lines, don’t go away. Your future all planned. That sounds interesting. So basically he, he hired me and sent me to Europe to do Formula One. So that’s actually the story of how it happened

Crew Chief Eric: Comes at a super exciting time in Formula One history, right?

This is the advent of the aerodynamics and the Y tires and all the sponsorships and the famous deliveries and the Marlboros and all the other brands that we can’t talk about or show on cars anymore. And don’t

Pete Lyons: forget, at that point, 73 was the same year that Shadow came in, followed by both Penske and vs.

Parelli Jones. For one point we had three separate makes of American car in Formula One. But it was, I think, was part of the reason Leon sent an [00:39:00] American to cover the races

Crew Chief Eric: and in so much as Can-Am has this mystique unto itself, the team, the name, the brand Lotus is also shrouded in a bit of mystery, right?

There’s so many different stories and hearsay and you’re there in the middle of it, in the fray with Colin Chapman and everyone else. Can you talk about your time witnessing Lotus and what was going down?

Pete Lyons: Not from any good insider perspective. They were one of the 15 teams, let’s say, that I had to keep track of.

I had to write two stories from each race, auto, sport, and auto week. And I had to keep track of chassis numbers for odds sake, which is kind of a joke, but we won’t go into that right now. So Lotus was here, but then there was McLaren Ferrari, Heskith March problem, whole bunch of them, you know, so that my time was split.

And so I didn’t live Shea Lotus for the whole period of time. They had some marvelous cars. They were fascinatingly innovative within the rules. My favorite was the wedge-shaped Lotus 72 that Emerson Foral drove for a [00:40:00] championship. I mean, that car, I’ve written a book about it and that car is just so elegant and interesting.

It was a car unlike any other, it was almost like a spaceship compared to a, a typical Braham or Laren.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, and the reason I bring it up is because things are happening simultaneously and we tend to fixate on a single point, or a single person or a single thing. But at this point, fellow Motorsports, journalists, Jerry Cromack is chronicling the story of Lotus that later became the book Chapman and his machines.

And so I’m wondering, you know, did you rub elbows with Rom back and was he able to share anything that he was working on with

Pete Lyons: you? I did know, Ja, of course. In fact, I visited him in Paris one day and he gave me an assignment. It’s like seem to remember, I can’t tell you what it was now, but I didn’t delve into it.

I mean, it was well known that he was a Colin Chapman fan. Oh, I was a bit of a McLaren fan.

Jon Summers: You talk about you, you knew Mike Sson and were were friends with Mike. Oh, yes, yes, yes. He was my landlord for some time. I believe. Mike Sson was the journalist who developed a close [00:41:00] relationship with Sana, and then SNA felt that he liked.

Betrayed his trust and you wouldn’t speak to him anymore. And there was a whole,

Pete Lyons: I know nothing about that. That was after my time and I, I can’t say a thing about it. I didn’t know that. My thought

Jon Summers: about

Pete Lyons: that

Jon Summers: was there must have been occasions where you were told things or overheard things or learned things just by being around the pit, just by walking from the shadow garage to the McLaren garage past the Ferrari garage.

There must have been things that you heard or saw or juicy bits of news that you didn’t want to write about.

Pete Lyons: Very little, but I was told things in confidence and I promised I wouldn’t say anything, and I’m gonna hold to that. Nothing earth shaking, I mean nothing scandalous, no bodies anywhere. There is something I can talk about.

Just to satisfy you, BKI Sims, who was at Braham one day came to me and he says. Pete, what do you know about that Chaparral that had the fans on the back and it stuck to the [00:42:00] ground? I said, oh, are you thinking of doing something like that? Then Beaky, he says, oh, the governor wouldn’t want me to say, but you, do you have any photographs?

And so I went into the Autosport archives and I dug through file folders, and they came up with two or three, four pictures that I had personally taken back in 1970 and sent to Autosport. Then I got on my Norton and I wrote down to, uh, almost straight to, uh, Gordon Murray, the designer at Bra. I says, BKI tells me you’re thinking of doing a ground effects car.

Did he? That was indiscreet of him. But the end result was I took those photographs on my bike riding down to where he and his wife lived on in the, it, it actually looked like a little cottage in the woods. It a pretty, and, uh, I turned up and his wife says, oh, yes, Golden’s expecting you, but he’s, uh, he’s out in the wood at the moment on his motorbike.

And presently I heard this trial’s bike coming, PA, pa, pa, pa. And. Gordon appeared coming outta the woods and stopped me, and he looks at me, he says, you can’t think about bloody motor racing when you’re riding this. [00:43:00] So we went in and I displayed my photographs and I told him what I knew about it, the Chaperral and how it worked, and what the effects were and so on.

And then I said, I won’t say a word about this until you’re actually ready to announce it. If you go ahead and do it, I want an exclusive on the story. And that was the deal. But the car actually came out after I had left Formula One, so I never wrote about it and it was many years before I wrote about it.

But that’s the kind of thing that you can get into, particularly if you’re accepted and trusted to a degree, they will tell you things, but on the understanding, you both understand that you’re going to keep it to yourself. People would say that Lotus is, were built a little too light. Well, unfortunately that probably was accurate.

Lotus did have a number of nasty failures that caused accidents. A team like McLaren was probably on the other side that, you know, they were conservative, which is why they finished races. I used to keep statistics and at the end of one year I figured out that the team with the [00:44:00] best reliability, the best finishing record was McLaren by quite a long bit, like something like 84% of the races.

Whereas other teams were down in the 50% range, they broke that often.

Jon Summers: Why were you able to perceive a difference

Pete Lyons: in the approach? Yes. McLaren, for instance, was much more conservative. They didn’t fly out and try to do something novel just because it was novel. They had plenty of ideas of their own. They made the interesting developments of their car, but they didn’t suddenly decided they needed to take a hundred pounds off the weight to the car.

You know, the idea is to finish the race, and they built cars to finish the race. My perception of it, they might say to something else, but at the same time they were qualifying on pole. They were doing fastest laps. They were making world champions. So you can’t say they were slow, but they were built in a kind of robust, logical, solid way, and they lasted through races.

Whereas Lotus’s tended to be a bit fragile.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s turn the page and talk about another team [00:45:00] that I think many people have probably spent time on unpacking. And that’s Tyrell.

Pete Lyons: Oh yes. I used to hear the story that they were built in a timber yard. A woodyard, I thought, oh yeah, sure, sure, sure. And it turns out to be absolutely true.

So stupid. I never went there. I mean, it was a matter of 45 minutes drive from where I was living in those days. I could have gone to Terrell, I could have gone to Lotus. I did go to McLaren. I went to a couple of other places, but I never went to some of the ones that, in hindsight I wish I had, in which case I would have walked into this timber yard.

Ken Carroll was, he sold a lumber and it would’ve been a, a woodyard piled with timber and sheds. And one of the sheds that you might not have looked twice at, if you open the door, there was the Formula One racing shop in it. So it’s true that they were building a in a timber yard.

Jon Summers: Ferrari’s Garage, east Easter Jaw.

He had some truth to it.

Pete Lyons: Oh. Oh, he called them the Galler East. That’s right, yes, that’s right. It was thanks to first the Coventry climax engine from Britain and then the Cosworth DFE engine that Keith Duckworth designed. [00:46:00] Those were the ones that were available publicly so that so many could participate in Formula One.

In those days, you did have Ferrari that built their own engines and gearboxes as well as chassis. And you also had BRM that did the same thing in England, and occasionally you had somebody like Al Romeo or at TS or Mara did that, but list all the cars on the grid. You had the Lotus’s that McLaren’s the Tyrells, the Brahams marches, uh, keep going.

They were all built around the Ford Cosworth DFVV eight engine. Yes. To the extent they were hot Rods garage East, perhaps some of them were actually built in garages like the Terrell’s were. But I know that the, the first shadow was started construction in the guy’s garage, literally his home garage. He pushed his wife’s car out and put the bare metal that they were putting together for the first shadow before they got their actual factory.

So yes, it garage east is accurate. But, excuse me, sir, that Mr. Uh, crime back, they were winning races.

Jon Summers: [00:47:00] It’s astonishing for me that this one engine packet, were they different or when you walked down the pit lane and stood close to them, was the construction similar, even though the livery and the wings were different?

Pete Lyons: Very similar because, let’s face it, they were all built by the same basic people. A lot of the chassis were actually farmed out to, uh, specialist that built things like that. So they were similar. They were built to the individual design, but they were riveted and glued together, and that probably the thickness of the metal was the same.

And all the tools and the, the workmanship was the same. Not all of them, but they used the same suppliers for brakes, for wheels and tires, suspension springs, gearboxes, almost all used a specific gearbox. So there was a lot of commonality. On the other hand, at the same time, you could see that the designers were trying different things, but it, it wasn’t major.

You know, they would change little shapes here and there and different suspension geometries and put their radiators in different places and try different body profiles and different wing [00:48:00] shapes and positions. So there was some difference, but it was variations on a theme, let’s say. Whereas in Kda, you know, the Chaparral had very little resemblance to a McLaren, to a Lola, to a shadow, to a Bryant, yes.

They tended to have big block Chevy engines and Hu and transmissions. Okay. And this, at the same time, they did have the same kinds of brakes and shocks and so on. And the tires all came from the, the supplier, Goodyear, I think, and Firestone for a while. So from that standpoint, they were the same. And yet the fact that.

You could do a different chassis. In the earlier Chaparrals, they had these aerodynamic changes that other people didn’t have. Even though they were using many of the same components, it’s still, they were, I think there was more variety in k and m than there was in Formula One.

Jon Summers: Formula One had more rules.

My perception is certainly that there was more variety in Can-Am and there was in Formula One, and I wonder how much the, you know, similar components and all of that led to Formula One being, I’m not sure if competitive’s the right word, but [00:49:00] certainly its popular appeal grew right the way through the seventies and its appeal to sponsors grew out the way through the seventies.

And I wondered how much of that was due to the fact that the cars were. Relatively similar. So you didn’t have the situation where Porsche came along and kind of won everything.

Pete Lyons: I’m sure you’re right. Yeah. The days of Mercedes having the dominant car and then Ferrari having the dominant car, it’s still an interesting spectacle to watch, but it’s much more exciting if you have different cars and different drivers doing different things on different tracks.

You know, in one track, certain car is good, the next track you go to, the other one has an edge, and sometimes the races are just dreadful, boring processions, but other times they’re just wheel to wheel and oh my God. Did you see that? So it’s Vila di.

Crew Chief Eric: I’m sure we could talk about Formula One and Canda all night, but let’s not give away all the details in your book.

So let’s switch gears into our final segment and talk more about your book and let’s talk about the journey of what I call 80,000 words and setting off. And you’ve written books before, but [00:50:00] let’s talk about. Why this book? Why now? Why put this compilation together? What inspired you to write basically your life story?

Pete Lyons: I’m going to turn 85 in a few weeks, and the morning of my 80th birthday, almost five years ago, I woke up thinking, ha, 80 years old. Who would’ve thunk it? I’ve had one hell of a life, and I think that was the germ. I, I can remember taking a piece of paper. Well, before I got outta bed, I, and I started writing down some thoughts, which over time sort of turned into the book.

I think it was just an idea until one day my wife said to me, her name is Lorna. She said, Peter, you should write your own life story now. Okay. You know, my wife isn’t giving me instructions. I can do that. And then totally serendipitously the publisher in England, Evro Publishing, Mark Hughes is the editor there, and he’s a wonderful person to work with.

I had done a couple of books with him before Lotus and Shadow and so on. We were talking one day and he says, Peter, have you ever thought of doing a book about your life? And [00:51:00] I said on, you should mention that, mark. So I sent him some samples of what I’d been kind of noodling up and he says, yes, yes, we’d like to see more of this.

So what really pushed it over the edge was the photos I could bring to it. The words are one thing, but I was blessed with having such a huge photo archive. Not only my own, but of my father’s before me and including childhood photos, and even back when he was a, a young man dating my mother. You know, he’s got photos and a lot of those are in the book.

And when Mark saw the wealth of photography I could offer, they got quite excited. And I thought, this makes a good book.

Jon Summers: With a normal biography, there’s maybe one or two childhood pictures, but I get the impression because your father was into photography. Those early chapters give a really complete picture of your childhood and sort of set the scene for the person that you become in later chapters.

It’s, it’s really an enjoyable experience. Those early chapters.

Pete Lyons: John, you make my heart soar. That’s exactly what I hope to come across. Thank you, sir.

Crew Chief Eric: How did you find it? Writing about [00:52:00] yourself and not writing for someone else. You had such a long illustrious career as a journalist, writing about other things, and you’re always that omniscient third party looking in and then, you know, reporting the story to us, the audience.

But now you’re reporting your life story to us, the audience. You maintain a sense of your journalistic style in your writing in the book, but did you find it to be a whole new challenge, really writing about yourself?

Pete Lyons: I’m not sure challenge is the right word, because it seemed to flow. You’re right, it’s different and the whole period of time, and I’m still feeling it is.

What bloody cheek to write about yourself, who cares? But I’m getting a lot of people that seem to like what I did, so that’s very gratifying. It’s sort of narcissistic to do a thing like this. If people wanna read it, I’m perfectly happy to do that. But it is different. You’re right.

Crew Chief Eric: So when you look back over your chronology with wiser eyes and maybe rose colored glasses in some ways, do you have a sense that your journalism, or even journalism in general in motor sports has evolved over this [00:53:00] time and putting together all of your memories and your memoirs?

Pete Lyons: Before I ever even thought of becoming a writer on that trip to Europe, the two and a half years I spent in Europe, I was keeping journals all the time. Diaries, I guess we call them in those days. I filled several notebooks or you know, composition books with, I’d have a few hours of motorcycle ride and then I’d stop at I’d sidewalk cafe for light lunch or something, and I’d pull out the notebook and I’d write down some of the things I’d seen in my sleeping bag that night in the campsite.

I’d write some more. And so I got used to writing what I had seen during the day, not necessarily anything to do with motor racing. I’m talking about the Alpine Pass that I just crossed earlier that day, and now I’m sitting at a gustof and I’m having a beer and a wienerschnitzel, and I pull it on. I talk about riding that my Norton across the A.

That was fantastic. That’s the kind of thing that set me up for doing what I did later and professionally.

Crew Chief Eric: And we’ve had other writers on the show, and they’ve talked about the editing process being one of the biggest hurdles, you know, getting their story told the way they want it to [00:54:00] be, because some editors said, well, you should take that out.

Yeah, that makes sense when you’re telling a story again from that third party view because you’re like, well, maybe we can take out that paragraph or two, because it doesn’t really add any value. But here again, you’re writing about yourself and what do you say to your editor when they go, oh, come on Pete.

We really wanna talk. You wanna talk about this? And you’re like, yeah. Right. It’s my story. I wanna tell it the way I wanna tell it. So what was the editing process like for an autobiography?

Pete Lyons: Well, particularly with Mark Hughes, it was marvelous. It was a delightful experience, but as you say, there are things that they want to take out, and I was able to dissuade him on occasion.

He accepted my reason for wanting to leave something in, but thick as this book is 550 pages. It would’ve been like 700 had they printed everything I sent them to begin with. So there had to be a really painful chopping off your left arm kind of thing.

Crew Chief Eric: There’s a value in that storytelling. I mean, obviously you have those 200 extra pages somewhere, but do you feel like part of your story is left untold by not [00:55:00] having that information published?

Pete Lyons: No. No. Honestly, I think Mark’s expertise, his vision, his view of it, his perspective is superior to mine. I really actually enjoy writing. I like to watch thoughts appear on the screen, and just because I’ve had the thought, it doesn’t mean it needs to be in the book. Just as an example, riding across France, I stopped for supper one night.

I had a experience in the restaurant that I wrote about for the book, but Mark thought, well, it doesn’t actually advance the story much. It was a matter of my first French restaurant meal. So I thought, oh, this is, I’ve heard about French dining. Let’s see what it is. So I ordered a salad and something else.

Presently the salad appeared and it was a very good salad, and I ate some of it. Then I put it aside to enjoy the rest of it with my meal, and I sat there and no meal. I sat there some more, no meal. Started crossing my arms like this and looking around. There was nobody else in the restaurant. I was alone.

Looked around and finally outta the corner of my eye, I saw the face of the waiter stick his [00:56:00] head out of the kitchen and he looked back and got back. And the third time he did it, I was ready. And I said, where’s my supper? And he came over and he carried a dish out and there was something about his posture and his movements, his deliberate motion.

He was telling me something like, and he put it down in front of me. Then he moved to take the half eaten and salad. I said, no, no, I want to have that. And he put it back and he just gave me this weird look and he walked away. Then I remembered that I’d heard that in France, they eat meals and courses. We eat everything.

I mean, I eat everything together. I’ll take some meat and then some potatoes, and then some salad and vice versa. In France, apparently you’re supposed to finish the salad and then that goes away, and then you have the main course. And I told that story. It was part of the adventure of cruising through Europe and getting to know what was going on there.

So that’s one of the stories that got put on the cutting room floor. Thank you for letting me tell it. Now,

Crew Chief Eric: inside of that anecdote is. Moral for younger writers who are looking for some inspiration from you. And, and I, I wanna expand upon [00:57:00] that to ask any advice for someone who’s sitting down and maybe considering writing their autobiography.

Not to mention writing an a novel or a biography or another type of book, but if you’re considering writing an autobiography, do you have any words of wisdom that you can pass on or, or lessons learned from your experience?

Pete Lyons: I won’t call anything I say is wisdom. No way. I often get asked when people know that I’ve been writing my biography, they say, oh, I’ve always wanted to do that.

I said, well, what’s stopping you? Oh, I know I don’t have time, or I don’t know how to write or anything. So I say, start simple. You know, just think of something that happened in your life. It could have been this morning, it could have been when you’re more five years old. Just put some words down on paper and I don’t know any other advice to give somebody.

It’s just to start developing it. The people so far that I’ve talked to that I’ve told them that to, I asked them a few weeks later, well, how’s the biography coming? Oh, well, I haven’t, haven’t actually done that. You know, so I haven’t helped anybody is the answer. I, I would seriously advise anybody to just keep a diary.[00:58:00]

Also do photographs. And I don’t mean just put them up on the cloud from your cell phone, keep them somewhere, get an office like uh, John has of your own photos. But the fact that my dad had this archive and I had an archive helped a lot with the book. But even if you don’t have that, but what you need to do is make writing a practiced thing that you do.

I’m not sure that the skill is the right word either, but if you just write and write and write and think about what you write, am I expressing what I felt like? What happened to me going to work today? What did I see that was different and what do I think about it? Stop and scribble down something.

Things like that. And eventually you’ll build up something and you’ll find that, you know, this reminds me of something happened when I was four years old and I see a relationship. This kind of thing has happened to me. So I, I think it’s a voyage of self-discovery, but you’ve got to actually do it. Keep rolling the boat.

Crew Chief Eric: Pete, at nearly 85 years young, it took you almost five years to complete this project. Yes. What’s [00:59:00] next? Is there something else on the horizon?

Pete Lyons: Well, I, I am in fact working with another guy on a book. I don’t think he’s ready for me to tell the world what he’s working on, but he’s a person who has a fascinating life story to tell, and I’m helping him tell it.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, Pete, we’ve reached that point of the episode where I like to invite our guests to share any shout outs, promotions, thank yous, or anything else that we haven’t covered thus far.

Pete Lyons: Let’s not forget this. This is available@petelyons.com. Lorna and I sell it. You’re all invited to go to pete lyons.com and uh, look for it.

And if you like what you see, there’s other places you can get it, but you get it. My, with my autograph here.

Crew Chief Eric: And folks, that’s a wrap on this incredible conversation with a motor sports author and historian Pete Lyons. From the Thunders Days of Canam to the drama of Formula One, Pete’s storytelling continues to bring racing history roaring back to life.

His passion, insight, and firsthand experiences remind us why motorsports isn’t just about speed. It’s about the people, the machines, and the moments that define them. Whether you’re a [01:00:00] longtime reader of Pete’s books or just discovering his work now for the first time, we hope today’s episode inspired you to dig deeper into the archives and relive some of racing’s most iconic eras.

So be sure to check out his website, www.petelyons.com to learn more and pick up a personally autographed copy of his latest book. My Travels on Racer Road, Canam and Formula One in the Golden Age from his website. And with that, Pete, I can’t thank you enough for coming on Break Fix and sharing your stories with us.

This has been a beautiful experience, reliving the past, an epic past in one of the best periods of motorsports through your words, and it’s been an absolute privilege to share your stories. So thank you for doing this. Thank you for writing the book, and we hope to hear more from you soon. Thank you to both of you.

It’s been a

Pete Lyons: great

Crew Chief Eric: fun day. And John, thank you again for coming on and sharing this journey with me.

Jon Summers: Thank you, Eric. Thank you very much. And thanks, Pete. Thank you.

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in [01:01:00] part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation [01:02:00] and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more [01:03:00] behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop Minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators fed on their strict diet of Fig Newton’s, Gumby Bears, and Monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you. None of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Welcoming Motorsport Journalist Pete Lyons

- 01:32 Pete Lyons’ Early Life and Passion for Cars

- 03:05 Backpacking and European Adventures

- 08:26 Transition to Motorsport Journalism

- 12:02 The Dangerous Era of Motorsport

- 15:31 Exploring the Can-Am Racing Series

- 31:12 Exploring Iconic Race Tracks

- 36:59 The Decline of Can-Am Racing

- 38:29 Covering Formula One in the ’70s

- 38:57 The Mystique of Lotus, the Reliability of McLaren and the Unique Story of Tyrell

- 49:49 Writing My Life Story and Advice for Aspiring Writers

- 59:13 Final Thoughts and Promotions

Bonus Content

There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.

Learn More

Get a copy of Pete’s latest book!

Whether you’re a longtime reader of Pete’s books or just discovering his work, we hope today’s episode inspired you to dig deeper into the archives and relive some of racing’s most iconic eras. So be sure to check out his website www.petelyons.com to learn more, and pick a personally autographed copy of his latest book My Travels On Racer Road: Can-Am and Formula 1 in their golden age from his website.

As Sir Jackie Stewart states in the book’s Foreword, “Pete Lyons was one of the best journalists in Formula 1 at the time I was racing.” Lyons himself writes that when he became obsessed with motor racing, “It felt like my true road.” He witnessed Chaparral, Lola, McLaren and Porsche create ever-more-monstrous Can-Am beasts to be tamed by the likes of Jim Hall, John Surtees, Bruce McLaren, Denny Hulme, Mario Andretti and Mark Donohue. His cameras, notebooks and typewriter also were there when Tyrrell, Lotus, McLaren and Ferrari were the dominant forces in Formula 1, with Jackie Stewart, Emerson Fittipaldi, Niki Lauda and James Hunt the World Champion drivers.

Immersed in this golden age of racing, Lyons brought a unique blend of evocative description and fastidious factual detail to his craft, putting his devoted readers at the heart of the action. This captivating memoir will transport the reader back to those times with key content like:

- Early travels, including criss-crossing the USA in his family’s pre-war Rolls-Royce and by Vincent motorcycle in the late 1950s, then discovering Europe’s racing scene as an impecunious wanderer in the early 1960s.

- Breaking into professional reporting from 1964 for the UK’s Autosport alongside his father Ozzie Lyons, with assignments embracing IndyCar, endurance sports cars, Formula 1 and more, and getting to know the great names in these worlds.

- Falling in love with the Can-Am upon its inception in 1966 and following this “big-banger” racing closely for seven seasons, during which “Riding with Revvie” — laps with 1971 series champion Peter Revson in a McLaren M8F — was among the highlights. Lyons’s travels “on racer road” took him all over North America by Volvo station wagon, Ford van and Honda CB750 motorcycle.

- Embarking in 1973 upon four seasons of global travels with the Formula 1 “circus’ and all the diversions that came with that, including time spent with Emerson Fittipaldi at his home in Brazil and a British rallying odyssey as Denny Hulme’s navigator.

- Around Europe, Lyons’s means of travel included his Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, a VW camper van that doubled as mobile office and hotel, and rented private aircraft that he flew to races himself.

- In his post-nomadic life, Lyons has been plying his trade ever since as a writer, photographer and editor.

“My Travels On Racer Road: Can-Am and Formula 1 in their golden age” is available in the U.S. from specialist and online booksellers, as well as on evropublishing.com. Pete Lyons’s new memoir is also available directly from the author, complete with his personalized signature, at his website: https://www.petelyons.com/my-books.

Evro Publishing books are distributed in North America by Quarto Publishing Group USA. Books can be ordered from Quarto by email: sales@quarto.com; phone number: 800-328-0590; or website: www.quartoknows.com Please use the relevant ISBN number when ordering.

Pete’s memories of Le Mans are vivid and poetic. He recalls the haunting beauty of night racing: glowing brake rotors, flaming exhausts, and the raspy growl of engines pushed to their limits. He describes the transformation of cars over 24 hours – from pristine machines to filth-streaked survivors. His writing captures the magic for those who couldn’t be there, making readers feel the grit and grandeur of endurance racing.