Few names in motorsport carry the same weight of endurance, adaptability, and charisma as David Hobbs. Across two unique decades and 20 attempts at conquering the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Hobbs carved out a legacy that bridged eras, manufacturers, and some of the most transformative decades in sports car racing history.

Hobbs’ path to Le Mans began not with open-wheel racing, but with innovation. His father’s groundbreaking automatic transmission – featuring four gears and a friction clutch – became the unlikely catalyst for his career. Racing family cars around Britain soon gave way to a Lotus Elite, where Hobbs proved his mettle by winning 14 of 18 starts in 1961. That success earned him a call from Team Elite, and in 1962 he made his Le Mans debut alongside Frank Gardner. Against the odds, they not only finished but claimed a class win and the Index of Thermal Efficiency. Hobbs was hooked: “Le Mans seemed like a very groovy race, and I was more interested in it than Formula One.”

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

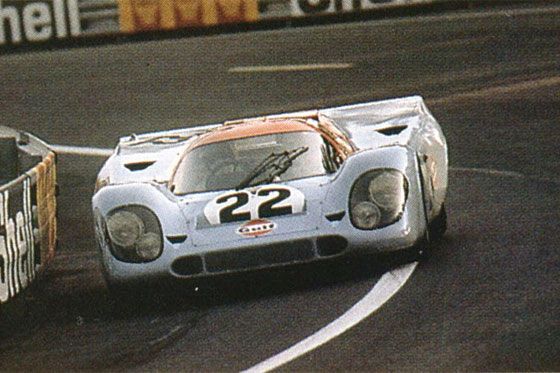

The 1960s were a whirlwind of experimentation. Hobbs drove everything from Triumph Spitfires to Aston Martins, often wrestling with underpowered or unreliable machinery. Yet his persistence paid off. In 1969, driving for John Wyer’s Ford GT40 team, Hobbs stood on the podium with a third-place overall finish – a moment both exhilarating and bittersweet, as it came during the final year of the traditional Le Mans start. Brake failures, fiery crashes, and mechanical gremlins were constant companions, but Hobbs’ resilience kept him in the fight.

Synopsis

This episode of Evening With a Legend features a detailed conversation with racing veteran David Hobbs. David recounts his extensive career, spanning over two unique decades, at the famed 24 Hours of Le Mans, providing in-depth stories and personal insights into his experiences from 1962 to 1989. From his early success with a Lotus Elite and a class win in his debut year, to his podium finishes in 1969 and 1984, Hobbs shares the challenges and triumphs of competing in various cars for major manufacturers like Ford, Porsche, and BMW. He also discusses the technological changes in motorsport, the evolution of endurance racing, and his transition to a successful broadcasting career after retiring from racing. The conversation is rich with anecdotes involving other racing legends, technological advancements, and thrilling moments from the track, making it a captivating recount of one man’s journey through the world of high-speed endurance racing.

- What initially drew you to compete at Le Mans, and how did that opportunity come about in the context of your open-wheel career? What do you remember most about your very first Le Mans race in 1962, and how did it shape your approach to endurance racing?

- You competed at Le Mans across nearly three decades—how did the cars, technology, and racing culture evolve during that time?

- What was it like racing for iconic teams such as Ford, Porsche, and John Wyer’s Gulf Mirage outfit, and how did those experiences differ?

- Can you describe the feeling of achieving a podium finish in 1969 and how that result compared to other milestones in your career?

- Which race or car stands out to you as the most memorable of your Le Mans entries, and what made it special?

- Le Mans is known for its grueling nature—what were some of the most challenging or unexpected moments you faced during the 24 hours?

- You’ve served as a color commentator for various disciplines of motorsports over the years, but what was it like to return to Le Mans and provide coverage for a race you’d participated in so many times?

- Looking back now, what does Le Mans mean to you personally, and how do you see your place in the race’s long and storied history?

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Evening With a Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to legends of the famous 24 hours of Le Mans giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

Crew Chief Eric: Tonight we have an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you sharing in the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing. And as your host, I’m delighted to introduce David Hobbs, who has enjoyed a long and diverse racing career with a 24 hours of Le Mans serving as a cornerstone of his legacy in international motorsport competing in the iconic endurance race 20 times between 1962 and [00:01:00] 1989.

He drove a wide variety of machinery, including GTS prototypes and group C cars for manufacturers such as Ford Mirage, Porsche BMW, and Jaguar. His adaptability and technical insight made him a valuable asset in multi driver lineups, and he earned several strong finishes, including a class win in 1962 at third place overall in 1969, driving for John Wire’s four GT 40 team, and then again in 1984 in a Porsche 9 56, David Hobbes’s.

Consistency, endurance, and charisma made him a fan favorite and a respected figure at Le Mans where his career spanned some of the most transformative decades in sports car racing history. And with that, I’m your host crew chief Eric from the Motoring Podcast Network, welcoming everyone to this evening with a legend.

So David, welcome to the show.

David Hobbs: Thank you very much, Jared. That’s a. A very complimentary opening statement there by yourself. Thank you very much.

Crew Chief Eric: No worries. Let’s begin at the beginning. What initially drew you to compete at Le Mans? How did that opportunity [00:02:00] present itself? What do you remember about your very first Le Mans race in 1962, and how did that shape your approach to endurance racing later?

David Hobbs: Well, actually, I hadn’t done any open wheel racing when I first went to the Mon. I was fortunate enough. I have a father who was extremely clever and had invented an automatic transmission that was way ahead of the field in as much as it had four gears instead of three, which most automatics had. And it did not have a, uh, fluid drive.

It had a friction clutch, which is automatically operated and it used very little power to run the gearbox. I had raised my mum’s my Oxford, first of all, that 1959. The 1960 IRA dad’s XK one 40, and then his company got an injection of money from an American company who could see a lot of future in his gear box, and it puts a lot of money into dad’s company and they all thought.

Of course, I helped them think that, that it would be a good idea to advertise the gearbox with racing in a small car. So they bought a Lows Elite for me. So in 1961, I raced a [00:03:00] Lows Elite, which was incredibly successful. I won 14 out of 18 starts with that car. We had some teaming troubles to start with, and then we employed a guy who came up to, I volunteer his services.

Who had been an ex Lotus employee, and he, uh, gave us a lot of tricks, how to light in the car, how to strengthen it, especially where the axles attached to the fiberglass shell. So I had a very successful year with that. In 1962, I got a call from Team Elite, which was run by Clive Hunter at the time, and he ran two or three Lotus Elites in Lotus colors.

And of course they had a stick ship. And they asked me to drive with them at Le Mans with Frank Gardner from Australia. So we dually assembled in a little village just south of Le Mans, to do the 19 62, 24 hour, and that was my first run. Now, to say that I was very pleased would be an understatement because when I’d started racing, not one of the reasons had been, to me, a big reason that I wanted to go racing was I really wanted to win.

Le Mans. Le Mans to me, seemed like a very, very groovy race, and I was slightly more [00:04:00] interested in Le Mans than I was in Formula One, actually. So, uh, I was very pleased to be able to go to Le Mans. And the team elite people were very helpful. Ron Bennett was a mechanic on our car, and Ron Bennett just died a few months ago at the age of like 94.

And Ron went on to fame, I’m not sure about Fortune, but so he went on to fame as a chief mechanic when Denny Holmes drove for the Irish to, and they had an incredibly successful career in, uh, big sports car racing, the Braham sports car, whatever it was, a BT 21. Then he bought a load of T 70 and it was all concrete in that Ron Bennett was a terrific mechanic.

Anyway, Frank and I, there was another car, John Wagstaff was driving in the other car. And anyway, we were fortunate enough to, um, last the 24 hours and it was incredibly hot, very, very hot weekend. So we didn’t have any rain, which of course was nice. And, uh, we won the class, well, we, we’d win the class, but we un won the index of Thurman efficiency as well.

And we were eight. They were all in the first British car home. All in all, it was a pretty good weekend. So I thought, well, this is a bit of [00:05:00] a battle. This race should be able to win this one of these days.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s take two steps back so we can proceed through the rest of your Le Mans career. So with that early Lotus, with the automatic transmission prototype that you were racing, most of that was done in the uk.

Had you raced anywhere else in Europe before turning laps at Le Mans?

David Hobbs: Funnily enough. In 61, we got an entry the Berg green thousand kilometers on the Norge life. And a friend of mine, bill Pinckney, was racing a Los 11 and it was very quick. So he and I went off to drive in the Nu Berg Green thousand Ks.

Now the gearbox caused a bit of a fracker because I had been told by a Lotus Elite owner the week before brand’s hatch that, why on earth would I racing car and automatic transmission? ’cause they were useless and they were absolute crap and just not worth why, why was I doing it? And I said, well, it’s the only reason I’m race is ’cause my dad’s gearbox.

Anyway, I beat him fairly soundly at Brand’s Hatch and also a guy called Graham Warner, who is the sort of [00:06:00] king of loads of elites, had a white and gray one. And, uh, I beat them both and won the race atranta. And the following week, we, the Bergy, we hadn’t been there long and I had a call, came over the Act Act Ha Hobbs, come to the office.

So I go to the office. They say Your car is one automatic Katrina. And I said, yes. It has said, well, it’s not homologated with automatic, one of your competitors has protested. So they moved me up to 1200 CC GT class to the 1600 CC sports car class, which in the end. We won. And now the Germans being very onic and very sort of precise, had a lot more money for sports cars than they did for GT cars.

And of course a lot more money still for a bigger sports car. So I ended up with about four times of money that I would’ve done if I had won a GT class. Needless to say, I still beat the aforementioned better anyway. So I had actually done one race overseas, which was the burging thousand Ks in 1961. And in fact, I went [00:07:00] again in 1962.

And this time my co-driver was Richard Outward. Of course, Richard Outward and I were both apprentices at Jaguar at that time, or had been just right up to that time. And of course, Richard went on to become the first guy to win the month for Porsche overall in 1970. So he and I drove with a berg ring as a quid pro quo.

I drove his former junior later that year at a place called Alton Park in England. And everybody thought I might come about fourth or fifth ’cause they were very seasoned former junior drivers in the race, a couple of whom were real Alton Park specialists. And I won that. So I won my very first single seater race and I won my very first international long distance race, Berg ring.

And then later that year, 1962. Clive Hunt asked me to drive with him and Frank, and we won that too. It all seemed pretty easy, but it definitely got more difficult as time went on.

Crew Chief Eric: There’s 20 attempts in your career at taking the Crown at Le Mans and [00:08:00] jokingly. When Patrick Long was here, I said the only person that’s got more attempts than Patrick is David Hobbes because Patrick’s got 16.

And so how do we summarize 20 attempts? Do we kind of take it in blocks and say what happened between the milestones 1962 and 1969? You were doing a lot of racing then. Open Wheel Le Mans, sports cars, endurance. Do you wanna talk about that period? Or we wanna just jump to the highlights?

David Hobbs: Well, as you say, I was doing a lot, well in the 62, I drove the Formula Junior then in 1963 by having won that race with Richard’s car in 62, the Midland Racing Partnership, were going to run the factory Lolas in 1963 in the Formula Junior Championship.

They asked me to drive. Which I did. So I became a Lola kind of worst driver, even though it was a private team, but they were racing under the auspices of the factory team. That was the year that the Lola March six came out, which of course was the forerunner of the GT 40. And so Richard and I drove that at Le Mans in 1963, which was an incredible [00:09:00] hassle.

It ran very late. We were down at the Bromley factory, which is where Below were in those days. Little factory in Bromley, south London. We went down there, well, they were finishing the car and they were running way behind. And then on like Monday of race week, Eric said, well, you two. I’d better go to the mom and sign on and get your medicals done and do the work stuff, and I’ll drive the car down tomorrow, which of course we did.

And, and he did. And he arrived and we were late for Cru hearing. And then of course, the French officials who weren’t very officially those days, it was a bunch of old guys who just were friends of the track. I mean, they weren’t real engineers, the technical team, they didn’t like the sloping back window.

They didn’t like the mirror, they didn’t like the trunk room for the box that gotta fit in the trunk. But we finally got practicing and started the race. It had the colos gearbox, which is a horrible box. And then the middle of the night we had problem. And of course at Le Mansr you can’t change or you couldn’t then change components.

You have to [00:10:00] fix them. So we had the gearbox apart on the pit lane, which was separated from the track then by a white line. And, uh, this was actually the corner, white House was still there. By the time you exited White House and got to the pits and the Dunlop Curve, you were back up to top speed. So in those days, the Ferraris and things were doing probably 170 parts, the pits.

And there’s old Malcolm Malone lying on the floor fitting with his kibo. Anyway, when they put it together, it only had three. We had to leave one out going later on in the evening, well about five o’clock in the morning, it was just starting to get a light. I went down into White House and it just sort of selected neutral.

I couldn’t get it into, so, you know, you go whistling to White House about 150 mile an hour. Anyway, I crashed the car and um, Eric was very disappointed in everything. Not as disappointed as I was probably, but so that’s what happened in 63 and that kinda relegated me on people’s driver list. And in 64 and five, I drove for Triumph in the Spitfire.

I drove with the Skid School specialist from Holland in 64. We [00:11:00] finished, I don’t know how well we did in the class.

Crew Chief Eric: Third in class,

David Hobbs: were we?

Crew Chief Eric: Yeah.

David Hobbs: Better than I thought.

Crew Chief Eric: Fourth, the second time.

David Hobbs: Well, the second time course, he crashed it at White House. We were four. There must have been only four cars in the class.

Crew Chief Eric: I’ve got the official records in front of me

David Hobbs: in 64. I drove for Team Lotus in there. Lotus Corina. Over here in the States a couple of times at uh, Marlborough and at Road America. Fun enough, 65. I then started to repair my credentials a bit. Colonel Ronnie Haw, who ran a Ferrari concessionaire in England and who ran some very successful race cars, asked me to drive one of his cars for a chap called Mike Salmon, who was also a very experienced driver, but we were only an adino, which he was as, it’s funny enough, I mean it’s, yeah, Richard Ford Ferrari is based around, we only lasted about an hour.

Something broke, I can’t remember what it was. And Richard at was driving for him with David Piper in a P three and that broke P Courage and Roy Pike and American Driver. [00:12:00] I think they won the GT class in, in the GTB or whatever it would’ve been in 1965. So there we, now we’ve got what, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 racers and only one class went to talk about in 66 I was racing at Lola T 70.

David Fletcher was the guy that ran it from Anso Station in Long Melford in Suffolk. That was a beautiful car. We won quite a few races in now. So John Serty was running the Aston Martin Lola project and he asked me to drive with him, but he and Aston Martin didn’t get on well and the engine was not very powerful to be truthful.

It was a big V eight and it was a bit heavy and it wasn’t as powerful as the chef, the Aston Martin people kept saying it was the car. And Eric broadly kept saying, well. It’s not the, it’s the engine. So I did quite a bit of track testing with the engine, trying various things and couldn’t really get it to go very fast.

Ironically, unbeknownst to them at the time, I was secretly testing the Jaguar [00:13:00] XJ 13 with the new Jaguar V 12 engine, which was a twin overhead cam V 12, which was extremely powerful, gave 570 horsepower, which back in 1965 was a hell of a horsepower from a normal aspirated engine. So I could, I could tell exactly which problem was in this, between the engine and the uh, and the car.

Anyway, we went to Le Mans. While we’re at Le Mans. John, who was not the easiest guy to get on with, had a big row with asin ’cause he wanted to change the sparking plug type from like Lucas or NGK or whatever it was. Champion Spark plug to some other mate. Anyway, the engine burned a piston in about four laps, so that was another one I didn’t win.

The other car went on for about an hour or two and then it faded. John said it was Aston Martin’s fault ’cause they changed the head gasket without telling him they said it was his fault ’cause he changed the spark plug. So I don’t know whoever’s fault it was. So that was 1966. In 1967, I drove, uh, what the hell did I drive in 1967.

Crew Chief Eric: [00:14:00] 67 was the Lola 68. You switched to John Wire.

David Hobbs: Oh, 67 was the Lola. Yep. Well, they driving 66 then

Crew Chief Eric: 66 was the Dino, and then 64 and 65 were the drive.

David Hobbs: Yeah, right, exactly. So I haven’t missed a car out. Nope. And then of course, 68 and 69. I drove the golf cart yet.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s talk about 1969. That’s your first overall podium.

Third overall, yeah. What was that like after so many attempts trying to get the overall win, now you’re, at least you’re up on the podium. What was that like for you?

David Hobbs: Fantastic. Of course, I mean, to be on that podium, which then was shattered what they’ve got now. But still in all, you know, the crowds came out on the track and the podium was above the grandstand, which of course was very different then to what it is now.

The whole pit area changed drastically soon after that. When they rebuilt the pits, did the whole brand new pit area, but it was incredible. It was slightly tainted because it was the last year of Le Mans Star. The old Le Mans star,

Crew Chief Eric: right?

David Hobbs: We qualified fairly well down the field. I don’t know, 10th or 11th or [00:15:00] something.

Jack Ys was protesting the Le Mans star. So I ran across the road, jumped in, and then put the belt on, going down the moan Strait, did a little, all that fiddling around the belts, which is of course highly dangerous, but everybody else is doing that too. Jackie of got strolls across the track, more or less dead last away.

Unfortunately for him, although it didn’t. Last, poor old John Wolf who had decided to drive the nine 17, which he had bought from the factory and he had a factory driver to help him. And of course the factory kept saying, well let you go start and then you take over. But John said, no, no’s my car. I wanna start.

And of course, he crashed at White House and was killed. Took out two or three other cars, including Chris a Amen in the factory Ferrari. Now we’re at the end of the second lap. We’re lap a bit ahead of Jackie and we stayed there for a long time until in the middle of the night. I had a break failure going into the Ballan hairpin.

So I go down the escape road, pumping the pedal, do a U-turn, go back to pits. David York, the team manager, who was a huge, huge [00:16:00] Jackie X fan, said It’s pads. And I said, well, it’s not pads, it’s because it’s all so sudden, you know, Nope, it’s pads, you do the driving, we’ll do the engineering. ’cause in those days, pad change was very long, very complicated.

Take the body off, take the wheels off. Then you have to open the calipers with those reverse type pliers and everybody’s wearing asbestos gloves. I said, well, I can tell you it’s not just pads. Anyway, off I go. And of course, can’t stop at the end of the pit lane, nearly run the pit marsh loader, do another slow lap.

They proceed to do the whole thing again. And of course there’s a little pipe across the top of the calip, which had been clipped by a wheel weight, which had been put on the inside of the wheel, which far certain people have been told to absolutely do not put wheel weights on the inside of the rim.

’cause there’s not enough clearance anyway to chip the hole in this pipe. So then they had to bleed the brakes. So now we are behind, and that’s where we, because that was a fairly harrowing race all around because after we got the brakes done and my next stint, I’m going down the Motown Strai and there’s two nine oh eights in front of me who had passed me and they were gradually pulling [00:17:00] away.

I mean, by a second or maybe. Second and a half a lap going through the kink. Four taillights go round the kink. And then there’s this flash of brilliant white light, which is obviously headlight. And then a huge orange ball of flame erupt. So I’m breaking and slowing down like mad and whistle around the kink for the brakes.

Hard on because can’t see anything ’cause it’s all dust and smoke. I’m aware this ball of fire is a blaze stuck to the guardrail on the inside. And when I break free, there’s the cab of the 9 0 8 bouncing down the road. So I’m looking where it’s going to go to decide where to pass it, and then the driver falls out and he’s bouncing down the road as well.

So it was my in lap. So I said to Mike, gonna be all, I said, there’s a dead driver down on the middle of the road. It’s gonna be an amazingly long caution flag while they clear everything up and blah, blah, blah. Well, the driver concern was Udo CHUs. And Udo was a bit on the, uh, let’s say Porky side a little bit overweight.

Years [00:18:00] later at the Porsche S Sport at Daytona. They said, Hamar, how are you, my man? Very good to see you in a big wave. This great big soul. Udo. I said, Christ, last time I saw you again in the middle of ah, oh no, I was not. That’s all. Everything was fine, you know? And of course, ultimately the other car that he had touched was Hans Herman, who of course then went on right at the end of the race.

They had that incredible dice with Jackie Ys, which he won. But if things had just gone normally for us, we would’ve probably been quite a long way in front of them. That race would’ve been for second, instead of which we came. But it was the podium and it was a great feeling.

Crew Chief Eric: So that’s 1969, and then you stay a household name at Le Mans for the next three years, so 10 years total.

Consecutive racing back to back at the 24 hours of Le Mans through 1972, and from 69 with John wy in the GT 40. You go to a nine 17 K, then to Nat with the Ferrari five 12 M. [00:19:00] And then in 1972 with a mantra, so that first decade of racing, how would you bundle it up?

David Hobbs: Course in those days, Le Mansr was completely different to what it’s today.

Say we qualified at three minutes, whatever we were doing, 3 56 or something in those days, David York, he said, well, for the first six hours we’re gonna run it four minutes and 10 seconds. Then we were reevaluated as the race progresses. And of course you had to be very careful the brakes because the brake had changed.

It was a long, long-winded business. And of course you couldn’t use the engine too much for braking because you didn’t wanna blow the engine up. You had to be very careful with the brakes. You have to be very careful. The clutches, you had to be very careful. The engine, of course now the flag goes at four o’clock in the afternoon and three or four drivers drive absolutely balls the floor all the way through the 24 hours, absolutely flat out.

And they hardly ever break. So cars breaking in those days was very common. And I was getting a bit fed up by then with, um, driving inferior cars like the Spitfire. I [00:20:00] mean, the Triumph people absolutely loved me. They thought I was a hero and that I should be driving much faster car than theirs. I had to agree with them, but you know, I’ve got the opportunity to drive.

So I did. And then of course, the Aston Martin was incredibly disappointing, as was the Ferrari of Ronnie Hall. Could’ve been Ronnie Hall’s car. Never really, he’s always winning races. Yeah, I was a bit upset 1970. As you say, I drove the nine 17. That too was awfully disappointing because Mike and I were a very good pair and we had the third car, which had a 4.7 liter engine, and the other two cars had the five liters, which was significantly more powerful.

But in the end, they all dropped out. And Richard too had a 4.7. Me and Mike were miles ahead of Richard and Han, Herman and Mike going past the pitch. It started to rain or just before he got the pitch. Anyway, he thought I’ll just do one more lap and of course gets to the Dunlop curve and runs into a car that’s already crashed in part there.

So we were out and if he hadn’t done that with a very good chance, we would’ve won the race. But I mean, you know, would’ve coulda, should have, doesn’t count. Unfortunately, [00:21:00] the biggest disappointment was 71 in that Ferrari. Mark Donahue and I run the poll everywhere we went. Daytona Sebring, he crashed at Daytona and at Sebring, which is very unlike Mark Donahue, never crashed.

We put about 2000 yards of tape on it at Daytona, and we, uh, finally ended up third at the 24 Yard Sebring. He had a run in with his absolute pet hate Pedro Rodriguez, who he hated with a passion for some reason or another. He said that Pedro ran into him, not once, but twice, three times. He kept on banging into me.

Well, I’ve spent how cock photographer was down there and saw it all. And many years later, like in about 2018, he said, well, that’s not exactly what I saw. It looked a lot more 50 50 not, it was not, definitely not old Pedro. And anyway, so. Roger Penske. Every time the engine came from Ferra, it went straight to Al Bart in California, who actually was a charitable, a special, but he would blueprint the engine and they were absolutely bulletproof.

They were incredible, [00:22:00] and they gave more power than they did from the fact. Well, we’re at Le Mansr on bloody Friday. Oh, Roger comes to waltz into the guards that shell guards on the main road. Just before you get to the airport, he goes and says, Hey, Ferrari, you’re gonna give us a brand new engine? Well, Don Cox, who was the chief engine, hit Mark, of course, and what he would’ve do was the chief mechanic.

They all said, no, no, no. What we’ve got, this engine’s fine. It’s running perfectly. There’s nothing wrong with it. Nope. No, we’ve gotta put the new engine. They overruled everybody and they put the new engine in, and at about eight 11 at night, we’re already a lap ahead of helmet. Marco and Chris Van Leonard, of course, went on to win the.

We were already a lap in front of them and the bloody engine blows up. Luckily not when I was driving. So every time the car broke, mark was driving it. The accident at Daytona was not really his fault because Vic Elford had spun when he had a tiger down at NASCAR. Three. It caused a lot of dust and everybody slowed up some twerp in nine 11 who we’d probably lapped about 40 times, ran into Mark at real [00:23:00] and his fault.

Uh, Sebring, I’m not sure. Le Mansr was definitely Roger’s fault. We shouldn’t have changed the engine. And then course we go to the box lamb with a six hour and I’ll again around the pole and leading. And the, uh, front hub broke all incredibly on Penser. So that was very disappointing. 1971. Then in 1972, the macho people asked me to drive the V 12 was Jean Pierre Yawe and we had the older car.

Our car was a year old Graham and Pess was a brand new one. Chris Aman was driving for ’em, I think had three cars in the race. Anyway, Graham and PEs were leading most of the race and of course won it. And me and old W eight were lying second for hours and, and it rained in the morning and Le Mansr in the rain is not pretty shy from the driver’s point of view.

I drove from 10 till two. I did a four hour stint from 10 in the morning till two in the afternoon, and I must have changed tires about three times. I had the most godawful. Tank slapper coming out of Arage by now, we’ve got the Porsche curves. But you know, in a car like that between [00:24:00] Arage and the Porsche, when you arrive at the Porsche curves, you’re up to about 190 by halfway there, the car just lifted off the road and I’m twiddling the wheel.

And I mean, suddenly the car, my heart went right up to my throat. I mean, that was one of the worst moments I had in the car. I just felt so completely helpless. I mean, tires weren’t touching the road ever. Floating along the top. But anyway, it hit a bit and luckily the wheels were facing the right direction.

And every time I came in I said, why don’t you let jump yeah out? What about him? No, no, no. David, you were doing fantastic. It’s fine. You keep going. You were doing wonderfully. You put another sur title. Of course, it suddenly dawned me that the reason they wanted me to go till two o’clock was so that ye could finish the Frenchmen in the car when he, when we came second, well, me and my wife Mags with about half an hour go, we set off for the, uh, club at the top of the Dunlop Curve, which used to be where they had all the celebrations at the end of the race.

So we’re about halfway then on watching the cars go through the Dunlop Curve. And I said [00:25:00] to her, hold on a sec. I don’t think our car went through, but I better just check. So we waited and then we saw everybody go through and I realized that our car wasn’t there. So I went back to the pitch and said, yeah, well poor Jean Pierre, the gearbox broke coming outta Moosa with about 20 minutes to go.

That’s another one we didn’t win. And then by then I got very involved with Formula 5,000 over here with Carl Hogan. So I missed quite a few years.

Crew Chief Eric: There’s a seven year gap where you started your. 10 year run at Le Mans. But 1979, your return to Le Mans after you took a break is really interesting because when I look at the records, not one but two Fords in the same weekend, how did you pull that off?

Driving with Derek Bell in one car and then with Vern Schoen in the other, and 79, you also went to a three man team instead of a two, two-man team.

David Hobbs: I’m not quite sure how that happened, but that was that Mirage, which had been designed and built by John Horseman for uh, what’s his name out of Phoenix?

Crew Chief Eric: Harley Clarkston.

David Hobbs: Harley Clarkston, exactly. How could I forget that name? I didn’t like the car. I think I was a [00:26:00] bit too tall for it, so my head got terribly buffeted around because it was an open car and my head got really buffeted around badly by the air and I wasn’t very happy in it. And I, I quite honestly, I wasn’t very quick.

And why they jumped me around that, I’m not quite sure. The best part of that weekend was that. It, it was my 40th birthday and Ford, France put on a hell of a party for us at the Champagne. You remember Mo Shandong had that? Mm-hmm. Club. We had a big party in there for my 40th birthday. That was a lot of fun.

That was the best part of the weekend. Unfortunately, I’m not sure that I did drive two cars. If I did, it was because somebody wasn’t feeling very well and they just shuffled the drivers around. It must have been something like that. Not quite sure what happened. Quite honestly. But I wasn’t very quick in either.

I drove with Jasso for a bit. Of course Joso Jasso was the little guy. So he was well and truly out of the buffeting and it blew me around a lot. I didn’t like that. So that was that year. In 1981, of course I drove with Eddie Irvine and the uh, M1.

Crew Chief Eric: Mm-hmm.

David Hobbs: Which was owned by the guy who was the manager of Pink Floyd.

Crew Chief Eric: Steve [00:27:00] O’Rourke. Steve O’Rourke,

David Hobbs: exactly. And Steve would ask me and Derek to drive for him at the beginning of the year. And we both drove at Silverton and we did quite well in a thousand Ks at Silverton in May. And then Porsche asked Derek to drive for them in the new 9 36, whatever it was. Yep. Off he went, of course in and won the race with X.

And so, um, I drove with Eddie. It wasn’t terribly quick. That car. The worst thing about that was it broke when I was driving down at Tat Rouge, but at about one o’clock lunchtime. So, you know, you’ve done most of the race. My rule of thumb at Le Mansr is, if you’re gonna break, break before dinner on Saturday, don’t drag all through the bloody night and the half the night day.

The one in with matcha, you know, with 20 minutes to go, oh my God. Talk about the pitch.

Crew Chief Eric: What’s interesting about this late seventies, early eighties period is you have still some of the legends of Legends. There’s you and there’s Brian Redmond and there’s Jackie Icks, and I don’t want to call you guys the old timers, but the veterans of Le Mans who had been around turning laps forever.

And then you [00:28:00] got the newcomers coming in, you’ve got the Hurley Haywoods, and you’re starting to see Bobby Raha show up from the US and all these different names all mixing together at Le Mans. What was that like with the new class coming in, competing against people like Hurley Haywood as an example?

David Hobbs: Well, of course Hurley ultimately won it a lot of time.

Uh, he was incredibly lucky he got into a couple of winning cars when they were already winning and he got popped in at the last minute. So he, he gets counted as a win even though he didn’t do much in the cars. Yeah, I mean, that didn’t really worry me or concern me too much. ’cause Le Mansr was still a much more technical race, not technical on this today, but he still had to drive carefully ’cause the cars weren’t as bulletproof.

Although the new era of cars like the 9 56 and then the 9 62, they were becoming much, much more bulletproof. Brake pads were still awkward to change. It wasn’t until the Audi came along in the two thousands and we had all this quick change where he changed the whole bloody hub, the disc, the pads, the whole damn lot.

You know, it takes you like a few seconds really. So I, I never really worried about the [00:29:00] different drivers by now. It’s becoming, I irritating to do it so many times and not win it. And that was getting a bit of an ache. So, uh, but I mean, but that’s racing. I mean, Tom Christensen president, can you believe he’s done what 14 times and he’s only been off the podium once.

When it broke, and you’ve gotta be lucky, ’cause I’ll never forget, he won one year with the German driver who was a DTM driver, whose name I can’t remember. And the following year they shuffled the teams around and Tom Christians goes and wins it again with perio or somebody. And the guy that he’d won with the year before ran the car outta gas.

He was told to come in and and kept going and ran the damn thing out of fuel. Why couldn’t that happen while he drive with Tom Christensen? He certainly would’ve happened if he’d been driving with me. So you’ve gotta be as lucky, as well as good. Obviously Tom Christensen was extremely lucky, but he was also very good.

Yeah, and it was nice when I’d been driving the BMWI didn’t drive at Le Mansr. I drove NM one, but it was not a BMW effort. I would drive A BMW over here in the states in that little BMW three 20 I, and then we had [00:30:00] the first March prototype, which was not very good. They sort of pulled out a racing for a bit and I went to drive for John Fitzpatrick and then had another resurgence in the eighties.

Crew Chief Eric: And that begins your long stretch of Porsche? Porsche. Porsche. Porsche, yeah. From then until the end,

David Hobbs: yeah. John and I were driving that whale tail 9 35 from Kramer, and that car arrived at Le Mans from the factory by Tuesday. It had never turned the wheel, put it together and finish it off and did race prep and it, it ran fless asleep for the 24 hours.

And it was a very quick car. There was a nice car to drive. Very good, very fast. And the factory were running the 3 9 56 ERs, the Rothmans cars, and they were all brand new. And we just thought one of these cars is absolutely bound to drop out. At least would come third. But they’ll finish 1, 2, 3. We finished fourth overall and won the GT class pretty comfortably.

I believe that was a good feeling to, to win the class of that car.

Crew Chief Eric: So right there, 9 35 into the nine 50 sixes, big transition, 9 56 [00:31:00] Single turbo versus Twin Turbo, and then the 9 62 being the longer version of the 9 56 versus safety reasons and whatnot. It brings us into the middle eighties, 1984. Your next podium.

It’s been a lot of years since your last podium. What were you thinking taking home that third place in 84?

David Hobbs: It was very good. So, so that sort of restarted my, uh, kindle of my interest in Le Mansr again. It was a good result. We couldn’t have done better, really. I mean, it was the best we could do with that car.

Then the following year he bought a 9 56. Skull band colors and I’m halfway between Mulan and Porsche Curves late evening I think, and the engine engine just stopped. I did what all good drivers did. I got out and I took the back of the bloody body off. Somehow I got the back off on my own. God knows how.

And of course I look in there. Well, the fell good. It is me looking at the engine. What am I gonna do with it? You know, what had happened was the fuel pump, it wasn’t like I blown the thing up. The fuel pump drive had broken, killed from factory. Um, he said to me, that’s the first time we have ever seen [00:32:00] break.

I said, well, you’ve seen one break now, mate. It was very frustrating. I mean, such a funny thing to break a bloody fuel pump drive. I mean, that’s sort of thing, it kind of runs for a hundred thousand miles. It’s not under any strain at all. It’s not like a, it may be a racing engine, but the fuel pump drive is not under any sort of strain at all.

So that was damn irritating. Philippe was a bit of a whinger ’cause he was a Formula One driver.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, so were you.

David Hobbs: Yeah. But a real Formula one driver. Yeah. When I talk about luck race morning is the warmup, right?

Crew Chief Eric: Mm-hmm.

David Hobbs: Changed the end on Friday like everybody else did. He had very good engine men, terrific guys.

All very good, very thorough. Finally ended up Saturday morning, I drive out the pits on the warmup lap, accelerate up the hills of the Donald Curve and the throttle stick wide open. So I do a whole lap on the key just slowing down. Turn the engine off, put it on, turn it off, put it on. They take the plenum chamber off and there’s a piece of rag down at one of the inlands.

They had left a paper towel in the plenum [00:33:00] chamber. About six o’clock in the morning we’d been duking it out with yo, so we finally took a fairly substantial lead. We thought this could be it now as sooner are we in the lead. Then it goes on to five cylinders. So I come in and I don’t understand any, everything working the right air go off again, uh, coming again.

Uh, they eventually took out the plug and disconnected the fuel. We drove ly flat out from like seven o’clock in the morning till four o’clock in the afternoon on five cylinders. So the thing was vibrating like hell. It’s a miracle. It all stayed together because we came third. Even with all that in and out, in and out stuff, it had burnt a valve, which of course, I suppose it happened with the rag just didn’t have enough fuel or whatever.

But that vital bloody warmup lap, it obviously started to burn the valve, which then eventually gave up the ghost. And, but

Crew Chief Eric: what I love about your stories is that it overlaps with so many other legends that we’ve had on the show so far. And what’s really fun about [00:34:00] 1984, it was sort of a catastrophic year for everybody.

Rick Nup told a story about being in the Lola Mazda with Jim Busby, and they’re having complications and issues with that car. You’re having issues, but still manage the podium. And Margie Smith Haas, who’s in the audience with us, talked about the big wreck that happened in 84 that she witnessed while she was driving her Porsche.

So a lot of things happen in a single race, but all of you there at the same time. It’s pretty cool.

David Hobbs: Yeah. I didn’t know what this other mayhem was going on around me, and he goes. I’m not interested in Rick Masden mis firing or whatever was, but I mean, I couldn’t believe it. John’s cars were very well prepared and I mean that starting throttle sticks open on the very opening lap.

I mean, I just couldn’t bloody believe it. It was just pathetic. And there we are. That was 84? Yep. 84. Was I driving? 85.

Crew Chief Eric: 85. You were still with Fitzpatrick in the 9 56 with Guy Edwards and Joe Gartner.

David Hobbs: Okay. We came like fifth, right?

Crew Chief Eric: Fourth.

David Hobbs: Yeah. Just off the podium because the following airport, old Joe was killed, wouldn’t he?

[00:35:00] On the Mosan Street

Crew Chief Eric: then it seems like if you can’t beat him, join him. So you went to Yost?

David Hobbs: Yeah. Well, John by then had lost a large sponsorship ’cause he lost Jay David when he went to jail for 20 years. A chief sponsor. So I drive around. Yeah, exactly. And we, Ryan, or Yes, there’s one more LA amount that you can shake.

A sticker I drive with Sol, he was a bit bigger than me, actually. He’s about six foot two or three. So we were pretty evenly matched on sides. One of the trouble with driving those little guys as you gotta change the seat every time he ever pitched up. But I drove a Sol and we were absolutely the favorites to win.

Best driver team, best car, best team. Well that was a year when they had dodgy fuel from the main supply there. Something got into the fuel or it wasn’t up to scratch. And for some reason that Raul and his crew who are absolutely bloody bulletproof, didn’t adjust accordingly. So Sorl starts to race and in about five laps he’s in with a burnt [00:36:00] piston and the the factory guys.

Immediately came in, made adjustments to the fuel float or changed the chip. ’cause by now, you know you’ve got the electronic, in the old days it was change the jets or change the float shower, do this or do, now it’s, you gotta change the chip and anyway, the bloody thing burnt out. I, I’m here, I’m riding R Old Bloody Yost and the engine breaks and we are the first engine to break.

Oh. Oh Christ. I couldn’t believe it. So that’s what I mean about you gotta be a bit lucky as well. Whichever way you look at it. It’s not all my fault. And I didn’t win. And then my last Le Mansr,

Crew Chief Eric: 1989 and a 9 62 GT one with Damon Hill and Steven Ankar.

David Hobbs: Right. Another cracking driver lineup. But Richard Lloyd had had that designer who worked with him a lot.

Little guy, English guy. Who had redesigned the 9 62, which he said had a lot more down force and no more drag. Well, we [00:37:00] were nearly 20 miles an hour slow on the straight, which at Le Mans, the kiss of death if you three miles an hour slow on the straight is bad. We all struggled on eventually, and of course the awful thing was that the entry was Porsche cars, great Britain.

They had about a hundred dealers there all there, and a great big camp and a big tent and a dining hall and crushes. What else? I mean, it was a very, very, very big deal. All these dealers. I mean we did, and it broke. I mean, it finally gave up the ghost, which actually we didn’t mind at all. ’cause we were floundering around.

I mean, you know, when I say 20 mile an hour, it might’ve been 15, but it was a massive amount slower down the street. And yet when you got to Porsche Curves, which was where it was, I was gonna be so fast as the Porsche curves, it wasn’t any faster than anything anybody else either. So A didn’t have any more downfalls, and B, it obviously had add a lot more drag.

Crew Chief Eric: When we look back over your 20 attempts at Le Mans, the good, the bad, and the unlucky. Yeah. As it [00:38:00] seems. What would you say was your favorite car out of all the cars you drove?

David Hobbs: I drove so many cars over the years. Course the track by then completely different than what it was when I went there in 1962. You know, Mulan was straight down to the Headin and dead righthander with all that sand on the outside.

Catch the UN wary in there. The GT 40 of wires were a beautiful long distance car. They had a wonderful gearbox out the Zf ZF as I call it, which had a beautiful shift. The only thing is you couldn’t change the individual ratios, so if you’re a bit short, you have to change the final ratio. Otherwise you could, that’s the only thing you could change.

You couldn’t change the individual ratios, so you couldn’t adjust to gearbox. But that was a great long distance car ’cause it had good visibility. It didn’t get too hot. Great gearbox, lots of room, and it had no vices. I mean, it didn’t push or over steer or do any nasty snap over steer. I mean, it was a really easy car to drive fast.

You just have to be careful the brakes. But in those days, be careful with everything. Then I guess [00:39:00] the next best car I drove would be the 9 62 of Fitzpatrick’s. That was a great long distance car. John Bishop of didn’t like them ’cause they were so expensive. He wanted people to use domestic engines like the shes and the Fords and the Dodgers and put them in chais like Lolas in March.

They never, ever got the job done because in those days, those American v eights were a bit prone to break. And the thing about the Porsche, it was absolutely bulletproof. You know, the only thing I didn’t like about it was it had a synchronous gearbox and over the years using the uh, human box, the LG and the Can-Am Cars and the DG and the Formula car.

Brakes were so good in those days that you could break right into the apex and then put it in the gear you wanted to go out of the corner. I didn’t do all that, you know, because I just thought that put more strain on the engine wasn’t worth all that bloody bother changing gear about a million times.

You just break like hell put it in the gear you want and then go, well, obviously with a synchronized gearbox you couldn’t do that, you had to go down to the box. But other than that, I couldn’t for fault. But of course the [00:40:00] other big difference with that is I had been driving cars with wings for some time.

You know, the first wing car drove, we put a wing on my load at four, 5,000, I mean, on the McLaren, but that suddenly, because the 9 62 had the tunnels, so it had a lot of ground effects. So it gripped, I mean it stuck and that took a bit of getting used to, I mean, not too much, but a bit. It was a great cut.

And of course it was so reliable. We didn’t have a cane or anything like that. But I mean, it was very good and it, it didn’t get too hot either. And. It had enough room inside. That was, that was a good car. A nice car to drive.

Crew Chief Eric: So you mentioned when we started this journey that Le Mans came to you very early in your career and as we know, first impressions or lasting impressions, but with your entire career when you factor in Can-Am and Formula One and Endurance racing and Le Mans, everything, did Le Mans keep itself at the top of the list for you?

Has it always been at the pinnacle?

David Hobbs: Yeah, I’ve always liked Le Mansr. I then of course, went on to do about another 10 from the TV booth with Sam Pose and Bob Vacher and a whole [00:41:00] bunch of guys. Well, we PN first and then Speed Beach. I don’t know. There’s something about Le Mansr. I went there for the hundredth anniversary two years ago.

I took my two grown grandsons. We went and stayed in a little hotel near, and we went to the, uh, PLO Onsen suite, which is in the old Goodyear grandstand, dead opposite the, uh, exit. So it’s a good spot. But boy oh boy, the walking, oh, Christ sake. We we’re about a mile, uh, just walk. And at my age, I don’t mind doing a bit of walking.

Oh, sure. I wanna walk a mile each way. And then of course to get around the pit. Don’t forget it, because you gotta walk back to get under the tunnel. And then, oh, if I go again, I want to be right inside and I wanna be able to take my car inside and do it properly. But Le Mansr to me, is a great track to drive onto, like the Daytona 24 hour.

It’s a bit of a Mickey Mouse track. Whichever way you look at it, you’re doing ridiculous speeds around that. Banking not quite so bad. Now they’ve got the chicane in, you know, the bus stop. But I mean, mark went there with, with the Ferrari, with Mark in 1971. I mean, we were doing like 210 into the banking, you know, and of course you [00:42:00] can’t see Dly squat around the banking.

’cause the car, once the car drops over, you can’t see out the top of the windshield. If you put any sort of sign across the windshield, you know, it’s a Sunoco and it’s, it’s a sunshield. I mean, you can’t see anything and you wanna be able to see, well, around the banking. You don’t wanna be to see what’s under your nose.

Then of course the infield is also tight except for the left sweeper in the middle. Now, of course, the bloody things flood it all night, so no point really. It sort of takes away from a proper 24 hour race, which includes darkness. But Le Mansr’s got such great curves and beautiful long. Yeah, I mean, even with the Chica, I never drove it with the Chicanes.

’cause 89 was my last year, and of course it wasn’t till 90 that they put Chicanes. They’re streets now. I mean, the Porsche curves were already there. Indianapolis has been moved back. A lot of stuff’s been moved back, so it’s a lot safer than it was in some ways, a lot safer. To me, Le Mansr is just a terrific race.

’cause if you’re gonna breathe for 24 hours, you wanna be on a long track like you’re going somewhere.

Crew Chief Eric: I’m glad you brought it up before because I think a lot of people may or may not realize that you were [00:43:00] commentating on Motorsport events while you were still driving for quite a long time. Yeah. And so to come back to Le Mansr and be a commentator, what was that like?

Did it give you a sense of maybe nostalgia you wanted to be back on the track? Or were you happy being in the booth?

David Hobbs: Well, I dunno. I was happy to be in the booth, but it was good to be back. And of course a lot of the people were still racing who were racing when I last did it. Can’t remember what my first year in the booth was.

It was probably about 1990. All the people I’d been racing with the year before were back in the race. That point of view. I knew a lot of the contest and they knew me too, so they would talk to me and I was with my son. Guy was also helping in those days. And then we had Lan, who was obviously very well known, was his efforts.

There was a great TV guy and a great storyteller, so I enjoyed those Le Mansrs with the tv I did quite a few of them. As I said, certainly to start with, for the first few years, everybody knew exactly who I was. I mean, if I went to do it now, no one have a clue. I was, but well, everybody’s about 15. [00:44:00] Well, they look it,

Crew Chief Eric: I know you talk about it in your book.

How did you make the transition from pro driver to commentator?

David Hobbs: I first started doing TV in 1976 because Ken Squire, who had interviewed me a few times was the lead announcer for CVS Force. And he said to me, I think it’d be good if you could come on board with me, because Graham Hill was gonna be his color commentator until he got killed in that plane crash.

So they said, we need somebody. He said, I think you could do a good job. So I go for an interview at CVS, which is an absolute unmitigated disaster. I go all dolled up gum, a blade and tie and all that kid on. ’cause the guy I’m being interviewed by, whose name was Clarence Cross, was the vice president of sport who knew absolutely nothing about racing.

Well of course I won the formula 5,000 check. What’s four, 5,000? Well it’s like Formula One car, but it’s got a production engine and Oh, so it’s not a Formula One there? No, it’s formula. Oh, okay. Anyway, I could tell I was on a losing wicked with this guy finally. I mean, the sweats running down my [00:45:00] back and you know, top lips all covered in sweat.

Horrible, horrible interview. So when he shook me by the hand, I mean if ever there was, don’t call us, we’ll call you. That was it. Well, as luck without it, I was a bit lucky. Oh, now here I was very lucky. That was 1975 in October, and I got a drive for BMW in the three CSL in the 24 hour, 1976, and I got a friend of mine that got me a deal with Coca-Cola.

We also did a deal with Benny Parsons, so he was gonna drive with me in the CSL in the 24 hour, and I would drive his backup car and the 500, both of which would have Coca-Cola sponsorship. So I’d stay over between the 24 hour and the 500. Now, Ken Squire has been working on CBS for. Saying you don’t wanna bother indie stuff and Formula and NASCAR’s where it’s at.

NASCAR’s where it’s at, NASCAR’s where it’s at. So finally, I guess to get him off their back, they send clients cross down to watch the Daytona 500 in 1976 being [00:46:00] late January, early February in the winter. And he lives in New York. So he and his wife came down and have a few days R an hour before the race, and Ken Squire had a radio show from the Hawaiian N one night.

He says to me, do you wanna be on the show? Yep, sure. So I walked down there from the Hilton and there is Clarence Cross with his wife. I’m sitting at their table. Then Ken asked me up, he does, people like Kale, Yarborough, and you know, Richard Petty’s there. They’re all there. All the, all the drivers are there.

So I go up and I had about three or four gin and tonics. So I right on top of the cam, I haven’t actually slid down the back yet. So he and I had a hysterically funny five or 10 minutes and all these NASCAR drivers all rolling around laughing like Helen. So when I go back to sit down, Mrs. Cross says to me, you shouldn’t be driving race cars.

You should be on the stage. So I said, well, don’t tell me, tell him, you know. He said, well, I see a different side of you now what I saw in the interview and then blah blah. So yeah, we’ll try and find something for you very much later on in the year, the Pocono 500, it was a champ [00:47:00] car race in the car car.

They wanted a driver who instead said he wanted to drive in the race, so I already pushed it and they put me on the 500 with Ken for Pocono. Anyway, it’s cut a long story short. I never missed a motor race with CBS from then until 1996 when I left to join Speed Bridge and of course was part of the team that did the 1979 Daytona 500, which of course would just beyond all expectation because it snowed up north, half the football games were canceled and they had an audience about six or 7 million.

They thought they were gonna get about 300,000. And of course, kale Yarborough and Donny Allison are duke it out for the lead and on the last lap they crash it, turn three and they hide up the wall. And then they both get out and start fighting and we both going crazy in the booth. Richard Petty goes on from a distant third to win.

He is 900th date on 500. And Bob Allison, who was second goes, goes around and he gets to the fight. So he stops and gets out of his car to help his brother. [00:48:00] You know, you just couldn’t have written a better script. And anyway, uh, so,

Crew Chief Eric: so speaking of scripts, and this is a question I’m planned to ask Bob Varsha as well when he comes on.

Yeah. Because I’ve been thinking about this, you know, you watch Formula One and David Thar is up there and he’s talking about this is what Ptri is thinking right now. And it makes me wonder as a commentator, how much of the stuff that you guys say when you’re on air is, okay, I get what they’re doing, or I empathize with the driver.

Or do you just flat out make it up? Oh,

David Hobbs: no, no, no, no. I mean, I’m the color guy, so I don’t have to do anything. It’s up to the Bob VAs and the lead difference to do all the difficult stuff. Remember whose birthday it is and who’s, how many races they’ve done and what they, you know, my job to say what’s going on on the track.

Sometimes I exaggerate a little bit, but generally speaking, I, I call a spade a spade. I mean, I don’t sort of pushy foot around. ’cause you have to be very careful with people like Bernie. You, you have to be very careful. Otherwise, the next thing you’d have me off the air, it was the same with nascar, the France family rule.

Like, you know, I mean it’s their domain and that [00:49:00] reminded me at 19 it’d be about 83 or four driver Fitz pass at the mall. ’cause I mean, I put my uniform on at three o’clock in the afternoon on Saturday. I didn’t take it off until these days. They all have showers and air conditioned silence rooms and they’ve got clean air rules and.

People washing their O overalls and their underwear and they have new gloves every stint and new helmets and all that stuff. We just had the old same stuff. So in the 500 that year, they had the yellow flag rule, which in those days you could race to the flag even though there was a yellow flag out, you might actually race past where the yellow flag was.

So I said, I just think this is a crazy rule. You know, someone’s gonna get killed on these days. It’s just absolute madness to race the flag when you got a yellow caution flag. I go to Le Mansr in June. This, the race is like 1st of February. I get outta the car between stints and I’m sweating like hell soaking when I’m walking back to what was our motor home, which was a little tiny two wheel caravan, you know?[00:50:00]

And Bill France is there coming to the race with Alan Berto and this limousine is pulling through the paddock area. And Bill Florence gets out of the car near am I what? And not so much as a, Hey, hey, hey Dave, how you doing? How’s the race going? Blah, blah. He gets, he says, there’s the boy that don’t like our rules.

I mean, I thought, good God, talk about a memory like a bloody elephant for the wrong thing. Not so much as a, if I’d been thinking, Carter said, yeah, and good evening to you too, bill. But yeah, you gotta, there’s the boy that don’t like our rule. I went, well that’s the best you could do. So, um, yeah, that

Crew Chief Eric: was funny.

Well David, before we switch to our very final set of questions, I got two from the crowd Uhhuh. People are dying to know the answer so I’m gonna do them in reverse order. Paul Robinson writes, please ask David how the group seven Can-Am compared to the cars at Le Mans. I lived near MidOhio and watched David and Denny Hume, Peter Revson, mark Donahue, all the races.

Paul is a huge Can-Am fan. So talk a little bit about the Can-Am days.

David Hobbs: Well, [00:51:00] I mean, the Can-Am was a really a part of the racing history in the United States that people absolutely love and like a lot of nostalgia things. Everybody thinks it was absolutely amazing and it was, the cars were great. One shoe mark was winning Formula One races, one after the other.

And then when Betel winning race, everybody, oh, show that Formula One. It’s the same guy wins the races. Well, for God’s sake, Canam 1967 to 1971, Denny and Bruce or then, and Bruce and Peter Revson came first and second in battle. Every race, Jackie Stewart won a couple. Peter rep might have won one in a, in a, I mean it was incredibly one-sided, but those were exciting cars.

The Le Mans cars, obviously when I first did Le Mans were, obviously the Canam cars were much bigger and faster. But towards the end, when those turbocharged engines, although they were smaller displacement, they had the same sort of horsepower, even more torque when those big V eights. But one of the nicest cars I ever drove was for Roy Woods in 1973, he bought Peter Revson, the [00:52:00] M 20, which was the last maclan, and we raced in, uh, Carl and black label colors, and one of the best racers I ever had.

Was I came second to Mark Donahue at Watkins Glen in 1973. He was in the 9 17 30, which was absolutely just ridiculously fast. I beat all the other nine 1710s, which had won the championship the year before. ’cause that McLaren, I could see why Bruce, well then Danny had won so many races because the car was just so incredibly good to drive.

Obviously huge horse of horsepower. Unfortunately Roy and his engine guy kept trying to get more and more horsepower out of it by making the engine bigger and bigger. You know, we’re up to 800 cubic inches. But the trouble is because they became totally unreliable. And, uh, we had quite a few engine failures, but that was one of my best ever races and that was a beautiful car to drive.

It was very sensitive. Change the rollbar a bit or change the spring. Change the ride height eight of an inch or quarter of an inch and you, you could really feel the difference. So it was, it was a great car. [00:53:00] So I liked those Canam cars, but of course in the end, the rules were you can run what you’d run.

And of course Porsche brung and I, the nine 17 and of course complains, oh, Porsche have ruined the sport. Well, Porsche done exactly what the rules said all along. So, I mean, tough shit. I mean, that’s, that’s the way, that’s the way it didn’t go. They came with a better machine.

Crew Chief Eric: Alright, take us back again to 1964 because Scott writes, can you please share the story about your commute to the thousand kilometers of the berg ring with sterling Moss?

David Hobbs: God Sterling had that terrible crash in 1962. And then I think prematurely retired. He went to drive and he just didn’t think he was up to scratch. But then many years later he said, I should have just stuck it out, he said, because I think I could have still done very well and I think he would’ve done.

And so Sterling has me drive, I think it’s a nine 14. Scott just tells me it was a 9 0 4. I was driving not a nine 14, so he’s probably right. Well, I’m sure he’s right, but I’m driving a guy called Lucky Kaner who won it the year [00:54:00] before in a Birdcage Maserati. Overall, he won it with, I think, driving with Dan Gurney.

So we were driving nine 14, I can’t remember where we were staying, but we were staying still of about 20 miles from the track. Berg green. Thousand kilometers in those days attracted about 120, 130,000 people. ’cause obviously 14 mile track, there’s plenty of room for them. But the roads weren’t really up.

John went Sterling in whatever he was in Sterling and Susan were. In the front. I’m sitting in the back and Sterling’s driving. He come to the back of this tail of traffic that’s about 10 miles long. Oh, Sterling just proceeds to overtake everybody going down the outside. Then they, then they move over and then somebody see him coming to the mirror and they’d move out.

So we’d just chop and chin, go down the grass road and then go past and it, it just scared the shit of me. I mean, we just, how we weren’t killed on that drive in. I have no idea. I mean, it was the most hair raising part of the whole bloody weekend. I mean, it made the race look like bloody time. It was hair raising.

We were running late because we had to get there. So [00:55:00] yeah, that was a very exciting drive. It was the most dangerous spot the whole weekend.

Crew Chief Eric: You mentioned to me the last time we spoke that Le Mans is one of your favorites, but also one of your biggest regrets. So when you look back over all your attempts at Le Mans, put it in perspective for everybody as a pro driver who always wanted to win the crown but never got it.

David Hobbs: Well, as you get older, you know, all this stuff sort of fades and it’s no good holding a grudge forever because I just didn’t like Jackie Icks because David York was infatuated with Jackie Icks. I’m sure that he saw a great opportunity at Le Mansr to slow me down by doing that bloody break pad change. He didn’t need it.

That’s one thing. And he also, we were leading at Watkins land. Me and uh, Paul Hawkins had a lap lead over Jackie Itch. And David, you, when I came into the pitch, he said, I want you to slow down ’cause I want Jackie itch to win the race. Which of course I did. But I mean now, I mean, Jackie and I like a couple of old brother, you know, Hey David, how you doing David?

He’s lovely to see you. And I think, yeah, Jackie, he said, you didn’t like me, did you? I said, no, I [00:56:00] didn’t like you at all. That’s racing. You gotta take the rough with it. Smooth. I didn’t win it. And of course Brian Re’s big regret. He never won them all. Bob Wallet. Neville won it and he won everything else.

They, both, him and Redmond won everything but they didn’t win Le Mansr and it’s like so many IndyCar drivers that they don’t win any 500. They don’t think they’ve had a career. The fact that I didn’t win it is regretful, but it was all 40 years ago. So see, love you. As the French would say,

Crew Chief Eric: well you’re still very active in the motor sports community as a whole.

What’s next for you, David? Anything?

David Hobbs: Nothing. This year I’ve, I went to concourse in Lakeland last week. Lovely affair, big crowd, lot of cars. I think my next motor racing thing is gonna be probably the Daytona 24 hours probably go there, so not much

Crew Chief Eric: on that. Before we wrap out, I want to pass the torch to our a CO representative David Lowe, for some final thoughts.

David.

David Lowe: On behalf of the a CO and Endurance racing fans around the world. I just wanna thank you for an incredible evening. Thank you so much.

David Hobbs: Well, thank you David. I appreciate it. I, I enjoyed being asked to be on it. And, uh, so, uh, yeah, [00:57:00] a lot of good fun, lot of good questions.

David Lowe: I look forward to catching up with you in the near future.

Thank you again so much.

David Hobbs: Alright. Thank you David.

Crew Chief Eric: And that concludes this evening with a legend where we had the pleasure of diving into the remarkable Le Mans’s journey of David Hobbs, a man whose racing career spans over two transformative decades at the Circuit de Losar from his class win in the early 1960s to driving some of the most iconic endurance machines for legendary teens.

David brought a rare combination of skill, consistency, and wit to the world’s most grueling endurance race. His stories remind us why Le Manss isn’t just a race. It’s a test of time, talent, and tenacity. If you wanna hear more from David Hobbes, be sure to check out his book, HaBO Motor Racer Motor Mouth, and follow him on social media at Mr.

David Dot Hobbs on Facebook. And Mr. David Hobbs on Twitter. We hope you enjoyed this presentation to look forward to more evening with legend throughout the season. And on behalf of everyone here and those listening at home, thank you David for sharing your stories with us.

David Hobbs: Thank you very much, Jack.

Enjoyed it.

Crew Chief Eric: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure getting to know [00:58:00] you and hearing your stories, so thank you again.

David Hobbs: Thank you very much.

Crew Chief Eric: This episode has been brought to you by the Automobile Club of the West and the A-C-O-U-S-A from the awe-inspiring speed demons that have graced the track to the courageous drivers who have pushed the limits of endurance. The 24 hours of Le Mans is an automotive spectacle like no other for over a century.

The 24 hours Le Mans has urged manufacturers to innovate for the benefit of future motorists, and it’s a celebration of the relentless pursuit of speed and excellence in the world of motorsports. To learn more about or to become a member of the A-C-O-U-S-A look no further than www do Le Mansn.org, click on English in the upper right corner and then click on the ACO members tab for club offers.

Once you’ve become a member, you can follow all the action on the Facebook group, A-C-O-U-S-A Members Club, and become part of the [00:59:00] Legend with Future Evening with the legend meetups.

This episode has been brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports as part of our Motoring Podcast network. For more episodes like this, tune in each week for more exciting and educational content from organizations like The Exotic Car Marketplace, the Motoring Historian, break Fix, and many others. If you’d like to support Grand Touring Motorsport and the Motoring Podcast Network, sign up for one of our many sponsorship tiers at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports.

Please note that the content, opinions and materials presented and expressed in this episode are those of its creator, and this episode has been published with their consent. If you have any inquiries about this program, please contact the creators of this episode via email or social media as mentioned in the [01:00:00] episode.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 David Hobbs’ Early Racing Career

- 03:37 First Le Mans Experience in 1962

- 07:54 Challenges and Triumphs in the 1960s

- 14:17 The 1969 Podium Finish

- 18:40 Racing Through the 1970s

- 25:29 Return to Le Mans in 1979

- 30:09 The 1980s and Porsche Era

- 31:16 Reviving the Passion for Le Mans

- 31:27 Unexpected Mechanical Failures; Race Day Challenges and Triumphs

- 33:50 Reflecting on the 1984 Le Mans

- 34:59 Transitioning to Joest Racing

- 36:34 The Final Le Mans Attempt

- 38:00 Favorite Cars and Memorable Races

- 42:54 Commentating on Motorsport

- 50:33 Audience Questions

- 55:03 Final Thoughts and Reflections

Bonus Content

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

Learn More

Evening With A Legend

We hope you enjoyed this presentation and look forward to more Evening With A Legend throughout this season. Sign up for the next EWAL TODAY!

Evening With A Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to Legends of the famous 24 Hours of Le Mans giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

The 1970s brought Hobbs into the cockpit of some of the most iconic cars in endurance racing. He piloted Porsche’s mighty 917, Ferrari’s 512M, and Matra’s V12 prototypes. Each campaign carried promise – and heartbreak. A blown engine in 1971 while leading with Mark Donohue, a gearbox failure in 1972 with Jean-Pierre Jaussaud, and countless near-misses underscored the brutal nature of Le Mans. Yet Hobbs’ ability to adapt across manufacturers and disciplines cemented his reputation as a driver teams could trust in the most grueling conditions.

Return, Reflection and a Legacy of Endurance

After a seven-year hiatus, Hobbs returned in 1979, driving Ford-powered Mirages and later BMW’s M1 under the stewardship of Pink Floyd’s manager, Steve O’Rourke, followed by a string of Porsches through 1989. By then, Hobbs was a seasoned veteran, balancing the demands of endurance racing with a growing career in broadcasting. His longevity at Le Mans – spanning from the early 1960s to the late 1980s – offered fans a living link across generations of racing.

David Hobbs never claimed the outright victory at Le Mans, but his career is a testament to the spirit of endurance racing. Class wins, podiums, and countless stories of mechanical battles and human resilience define his journey. More importantly, Hobbs brought humor, humility, and charisma to the paddock, making him a fan favorite and a respected figure among peers.

Le Mans is not only about winners – it’s about legends. And David Hobbs, with 20 attempts and a lifetime of stories, is indelibly part of its fabric.

ACO USA

To learn more about or to become a member of the ACO USA, look no further than www.lemans.org, Click on English in the upper right corner and then click on the ACO members tab for Club Offers. Once you become a Member you can follow all the action on the Facebook group ACOUSAMembersClub; and become part of the Legend with future Evening With A Legend meet ups.