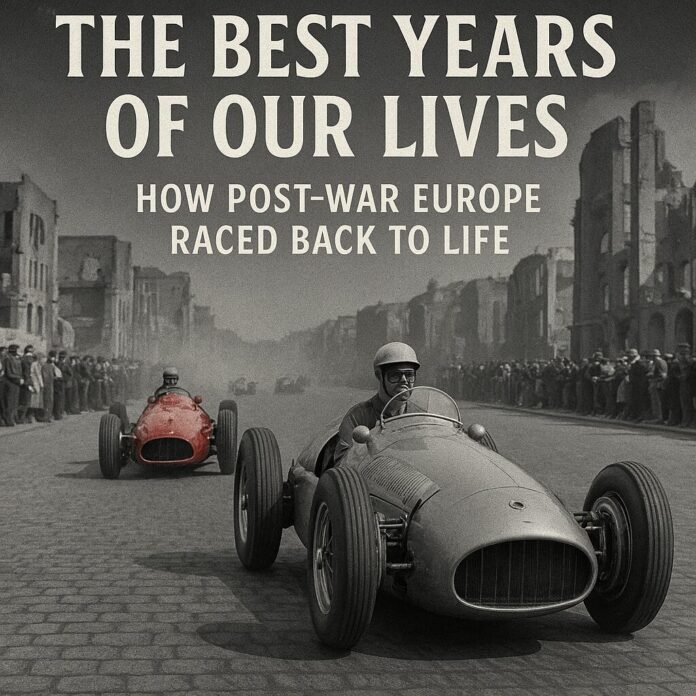

In September 1945, Europe was still reeling from the devastation of World War II. Cities lay in ruins, economies were shattered, and basic necessities were scarce. Yet, astonishingly, just weeks after the guns fell silent, the streets of Paris echoed not with the rumble of tanks, but with the roar of racing engines.

Why, in a time of hunger and hardship, did nations pour precious resources into something as seemingly frivolous as motor racing? And how did they manage it at all?

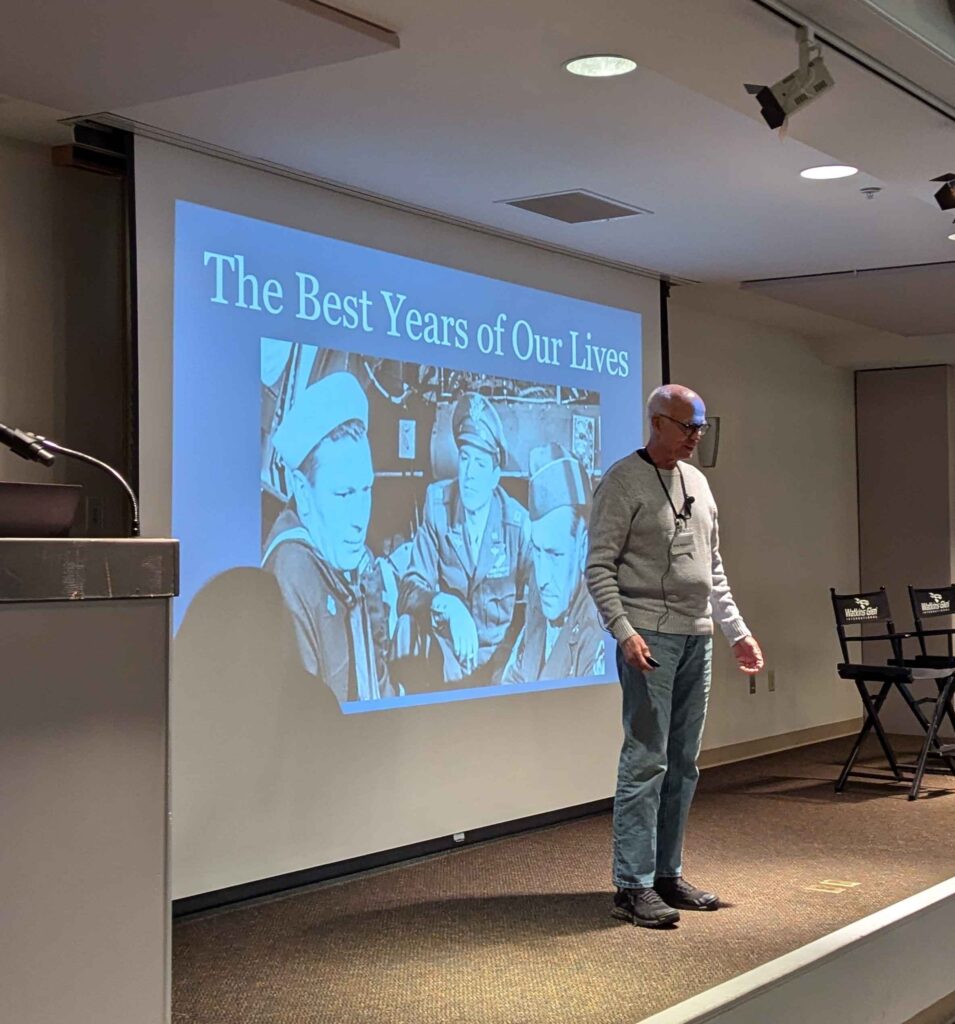

These were the questions posed by Skip McGowan, Professor Emeritus of Finance at Bucknell University, in his lecture The Best Years of Our Lives: The Rebirth of Post‑War European Motor Sports. His answer reveals a fascinating blend of economics, culture, and human psychology.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

Skip’s research into early 1950s Grand Prix racing uncovered two distinct types of constructors who built new cars after the war:

- Britain’s “gearheads in overalls” — small, entrepreneurial outfits like Cooper, Connaught, Vanwall, and BRM. These were passion projects, often run by engineers and mechanics funding their own dreams.

- The Continent’s “gearheads in suits” — corporately connected teams like Gordini, Maserati, Lancia, Mercedes, and Ferrari, backed by industrial giants or national interests, often with government ties.

Spotlight

Skip McGoun is the William H. Dunkak Emeritus Professor of Finance at Bucknell University and was a long-term Visiting Professor at the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia and at the University of Donja Gorija in Montenegro. He has presented and published on the history and culture of finance as well as automobile history and culture and served as Area Chair of the Vehicle Culture Section of the Popular Culture Association.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, supported by the International Motor Racing Research Center, explores the rapid revival of motor sports in Europe following World War II. Presented by Skip McGoun, the discussion delves into the financial and material resources, and motivations behind post-war racing. It contrasts entrepreneurial capitalism in Britain with national capitalism on the European continent, highlighting key figures and organizations in the early Grand Prix scene. The presentation also examines the psychological and cultural factors, such as the lingering wartime intensity and mechanical interest of returning soldiers, that fueled the resurgence of car racing as a means of maintaining the high-adrenaline experiences they had during the war.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports Series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer family,

Crew Chief Eric: the best years of our lives, the rebirth of post-war European Motor Sports by Skip McGowan. World War II in Europe left both victorious and vanquished countries devastated. Yet, within weeks of the end of hostilities on September 9th, 1945, an automobile race was held in Paris’s bla Deone. This presentation addresses the questions, where did the financial and material resources for an active postwar racing program come from?

And perhaps even more importantly, why were they expended in what many might regard as non-essential or perhaps even frivolous activity? Skip McGowan is the William h Cock Emeritus Professor of Finance at Bucknell University and was a longtime visiting professor at universities in Slovenia and Montenegro.

He has presented and published on the history and [00:01:00] culture of finance, as well as automobile history and culture, and served as area chair of the vehicle culture section of the Popular Culture Association.

Skip McGoun: My interest in motor sports really has been what’s under the table. You know, if you read my little bio in the brochure, what did it look like at the end of World War ii?

Okay, so we had this classic image, and yeah, it maybe looked like that for a few days, you know, maybe even a few weeks or it looked like that in New York City. But there are other places where things were very, very different. The end of World War II looked like this in Britain. It looked like that in France, Germany, Italy.

But what surprised me was that within weeks of the end of World War II, there was an automobile race in the bar de bologna. So the question I had been asking myself, maybe it’s two questions. How and why did this happen? First of all, there’s the question, how is we’re looking at a place where there was considerable.[00:02:00]

Deprivation. You know, there were shortages of food, shortages of cash, shortages of all sorts of materials. So how did they manage to put together a racing program so quickly? But the other question, of course, is why were these scarce resources devoted to motor racing? I mean, because obviously there are a lot of other things that could have been done with them at the time.

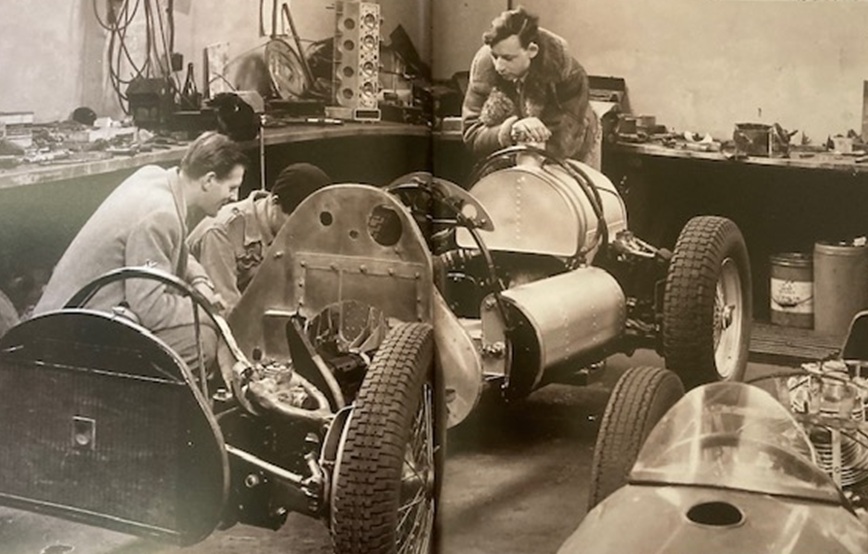

To approach this, and I cannot pretend that this is any sort of scientific approach, but I took a look early 1950s Grand Prix racing shortly after World War ii. Of course, they were racing automobiles that had existed before the war, but what I was interested in was when new vehicles started being built.

So I took a look at all the vehicles that had raced in the early to mid fifties, and I came up with a list of those that had been designed and built after. The end of the war, and that had raced in at least several races over several years, [00:03:00] not just the ones that maybe were one and done that showed up and then disappeared again, but ones that hung around for a while.

These were the major players, and the Hess represent the cash flows. I’ll get back to this a little later, but I wanted to show this down because what I wanted to focus on here were the constructors, you know, as kind of the heart of this whole process. So who were the people who built the new vehicles that participated in this very early Grand Prix racing?

And it turns out there were 10 of them, five of them were from Britain, five of them were from the continent. The five that were from Britain were largely constructed by. Businesses with mechanical interests. To kind of rephrase that a bit, they were built by gearheads in overall playing with their own money.

I don’t mean this to be pejorative because honestly, the more I read about the folks who did this, the more respect I had for them and not just respect, I liked them. These were people I would’ve liked to have known, and this is who they were. We had [00:04:00] HWM Cooper, connot Van Wall. And BRM. Now, the continent was a little different.

These were businesses that were more or less corporately connected, and I would describe them as gearheads in suits playing with someone else’s money. So they didn’t wear overalls, they wore suits, they didn’t use their own money. They were using someone else’s money. So we had Gordini Maserati. Macho Mercedes, and of course Ferrari.

Just a few observations here to begin with. The groups illustrate two different forms of industrial organizations. The British companies were really representative of what you might call entrepreneurial capitalism. Really, this applies almost across the board in the industrial structure. Britain was dealing with individuals who started their own businesses.

Maybe they grew, maybe they didn’t, but it was a very individual thing [00:05:00] versus what we saw in the continent, which you might refer to as national capitalism. The idea being that there were groups of related industries. They were associated with certain financial arrangements. They probably had close connections with the government.

So we had really smaller organizations, larger organizations, but as I say here, the motoring industry or the racing in. Was really representative of something that was much broader phenomenon. Now, I did use the term gearheads, but the idea was that regardless of the type of organization, it all involved someone that had obvious personal motivations in racing, talking about money, which was kind of how I entered into this interest.

Was construction really a real business or was it something else? Now, the more I looked at this, I realized that what went on there, and not surprisingly, [00:06:00] because we’re talking about the same era, was what we’re seeing in these early days of post-war racing seemed to me to resemble the early days of rock and roll.

You had garage bands, and in the case of Connot and HRM, these were literally garage bands. They built their cars within their garages. Cooper began as a garage band, but it’s kind of like a garage band. They got a recording contract. Okay. So they were able to kind of move upscale from their origins. We also had groups with wealthy parents, so Van Wall.

Was an interest of Tony Vanderwell who had made money with thin wall bearings. And in the case of Maserati, lots of details here. This was Ori who had a lot of other industrial interests. Okay. And Maserati was among them. So the racing activities received contributions from these other larger industrial [00:07:00] concerns within the group.

You had groups with what I might call gullible parents. In other words, someone was willing to. We’re able to convince someone else that racing was a good idea from a business standpoint. So supposedly launch of getting involved in racing would help sell launches. This is the one, honestly, with Mercedes that kind of baffles me because it’s like, okay, if we race, we’re gonna sell Mercedes.

And we had an unfortunate person who was abandoned by their parents. Gordini was very closely associated with sim c. But Simcock kind of cut ’em loose when the cars deviated too much on the track from the ones that he was trying to sell. You hear little bits and pieces of launch A going bankrupt and all of its.

Racing assets being transferred to Ferrari, and you see little bits and pieces suggesting that Fiat was the one that [00:08:00] orchestrated this transaction. And I can’t help but think that somehow the Italian government was involved. In preserving the presence of the country or some sort of, you know, national Italian product within racing.

This was certainly the case prior to World War ii, and I’m not sure that this industrial governmental relationship. It wasn’t still in effect after the war. VRM is a little different. Okay. We had this group of really significant British industrialists coming together to produce kind of a British automobile.

I’ve not seen anything that indicated a direct involvement with the government. But at the same time, all of these folks were plugged in, you know, and if it was necessary in some way to have the government kind of grease the skids for this project, I’m sure that they were able to arrange that it could [00:09:00] be done.

Bottom line is pretty much every one of those vehicles and every one of those constructors was depending upon some sort of handout from someone. The only one of these that I think you might argue as a business would be Cooper, but Cooper. Was probably the only one that actually turned into a success at actually selling a product that someone wanted to pay for.

They started out as a garage band, like a lot of the others. So then the question is, aside from these handouts, was there any other money flowing in. To this process that might have turned it into some sort of business. So here’s where I get back to this. So we did have two sources of cash flowing in. One was from sponsorships and the other was from the promoters.

Even those cash flows are not so easy to understand. First of all, the sponsors had to make money. So you assume that, okay, the sponsors were using this as. Kind of a marketing tool, [00:10:00] but it’s hard to value marketing. You really can’t say that, look, you know, we put this much into sponsoring racing, and we can expect to get this much in sales out of it.

You know, I did make a presentation about this last year, and there are lots of intangible benefits that companies believe they can realize from sponsorships. So it would be hard to argue that this is like a strictly business activity. Promoters had to not lose money. One of the things that I always found interesting was it looks as if these promoters of these races immediately after World War II were not money making organizations.

They were clubs, regions, just. Creating some sort of activity, and I noticed in the presentation it was mentioned that NASCAR kind of stepped in as a business because the aaa, and I forget which the other organization weren’t making a go of this. Again, it does not appear that originally this could even be referred to as a [00:11:00] business, but at least they could count the cash at the end of the.

Okay, so they could say, look, you know, we’re providing this service, we’re getting this much money in. As a result of doing that, that’s almost as close as it came to business. There had to be more going on. Obviously something else was driving this revival of racing right after World War ii. So quickly keep in mind the two questions that I posed up front were how.

And why this was happening. So the how, at least in one sense was that we’re seeing handouts in various ways to construct these vehicles. You know, we’re seeing money coming in from sponsors for something that the sponsors felt they were getting out of it, although I can’t help feeling that these almost were handouts from sponsors as well.

Yeah, sure. You can kind of sell that and say that this is a marketing expense, we’ll put this money in. But basically, and people wanted to go to the races, they wanted to [00:12:00] hang out in the pit areas and meet the drivers and those sorts of things. So, you know, hard pressed to consider that business. And a lot of the races were organized as mainly just, you know, kind of public events.

You know, the money there is pretty peculiar. There were other advantages that kind of facilitated. Racing right after World War ii. First of all, one was that a lot of the businesses in the war really had made money, so the money kind of came out of the war. Vanderwell, I imagine, made quite a bit of money selling bearings during the war.

Another thing was there was a surplus of reasonable pavement. It was not necessary to really spend a whole lot of money constructing facilities. I mean, this could be done on the old aircraft tarmax that, you know, were existing from the war. There was a lot of scrap around. It was interesting to, I mean, I may get this wrong, but you know, Cooper’s original chassis, they took the front ends from two old Fiats and cut ’em in half and put them together back to [00:13:00] back.

But of course, I think what was interesting is the fact that this could be done so inexpensively that they created kind of a market for inexpensive vehicles that other people would purchase. But yeah, there was a lot of stuff flying around that they could work with. And finally, nationalists sentiment was still running high.

You know, the Italians were still interested in having a. Italy compete in some way. The British wanted to see Britain compete in some way, so you come out of the war with actually some profits from the war. You come out with some good places to race. You come out with kind of a desire still to compete.

But I think there’s more, and I think it’s a little more subtle. When I read a lot of the, uh, things that are written about this area and about the early post-war racing, a lot of times they say, well, people just wanted to get back to normal. People wanted to get back to doing the sorts of things that they had done before the war.[00:14:00]

Forget about the war. Get back to normal. Remember, this is racing. This isn’t like going bowling like I see on the billboard out there. The question is why racing? We need to consider. The people who wanted to get back to normal weren’t the same people that were normal before the war. They came back differently.

You know, I chose this image because, you know, there’s a suggestion that the original biker gangs after World War II were, you know, were made up gis. So yeah, okay, we wanna get back to normal. But the people who were getting back to normal weren’t the same people. How are they different? I don’t know how accurate some of these characterizations are.

We turned into Gearhead Nation. Everyone in the war to some extent, had to deal with something mechanical. They had to know how to take care of it. They had to know how to repair it. So we had a nation of people that were really mechanically inclined. And [00:15:00] mechanically interested and in support of that.

Now you can read this quote from Raymond Mays. And Raymond Mays was certainly noted for using hyperbole when it served his interests, but he anticipated this phenomenon when he was soliciting contributions in order to. Create BRM. Okay, so one of, one of the rationales he gave was that this would exist.

He saw all of these people coming out of the war with this mechanical aptitude in the mechanical interest. Second, people wanted it fast and loud. I’m not sure that this is anything new, but the war had been fast and loud. And people wanted to continue with the fast and loud, and this is the one I think is maybe the most subtle, but the most significant people came out of the war as adrenaline addicts.

Life was just never as exciting. You know, I [00:16:00] remember reading about the settlement of the West. You know, after the Civil War. I can’t help thinking what it was. A lot of people came out of the war saying, look, running a general store in Connecticut just didn’t have that thrill anymore. So I’m gonna go out and do something a lot more interesting.

And I happen to run into this in one of the emails that I get from the Veterans Administration, so maybe this wasn’t just a post-World War II phenomenon, someone thinks that there is still such a thing as an adrenaline addiction out there. So my underlying argument was that despite what the literature often says, people just wanna get back to normal and do normal things.

Racing was not a return to post-war normal. It was a continuation of the wartime intensity. It was a way for people to capture the best years of their lives. Now, I don’t know how many of you have seen the movie or remember the movie [00:17:00] Dana Andrews before the war had worked at a soda Fountain, comes back from the war and you know, these three guys were sharing hop back to the hometown.

Frederick Marsh had been a banker. I can’t remember what Harold Holland’s job had been before the war. I wanna focus on Dana Andrews. Okay. He was working at a soda fountain before the war. In the war. Obviously he had been a captain and he was a bombardier, and I think a beat 24. Big difference between pre-war, life and life in the Army Air Corps.

So he comes home and it turns out his wartime marriage essentially fallen apart. He shows an interest in Frederick March’s daughter Theresa Wright, which doesn’t exactly make Frederick March too happy. You know, you, you can kind of picture, this is actually a C, great movie. You can picture the situation he’s in.

Can’t go back to doing what he did. He can’t go back to normal. [00:18:00] So what happens in the movie is he ends up in an aircraft boneyard where all of the surplus equipment is being torn apart and scrapped. So he climbs into a B 24 and he sits down in the Bombardier’s position. And you kind of get the parallels there.

The aircraft was post-war surplus, but in a sense he’s kind of looking at himself as post-war surplus as well, and the foreman and the, uh, scrap art comes up to him as what, what are you doing there? And is subsequently kind, you know, sympathetic that he’s returned to the best years of his life, which was sitting in a plexiglass canopy.

Dropping bombs. Probably the only person in greater danger than he was was the tail gunner, but it was the best years of his life. It didn’t just happen in a movie. You can read this closing quotation that really [00:19:00] zeroes in on the motor racing situation. Okay. Abe Caee was one of the principals in founding HWM.

So you can see that he raced, of course, before the war, raced after the war, which was probably the closest he came to what he had done during the war, which he always regarded as the best years of his life. So the how of racing. People who had a personal interest in this in one way or another we’re able to scrape together the money and the resources to do it.

The key though is why did they do it? And to me, I think this provides one of the best explanations of why they did it. They just weren’t the same people they were during the war and racing might have been an activity that was as close to recapturing that emotion as anything else they could do. Thanks very much.[00:20:00]

Kip Zeiter: Thanks. That was great. Do we have any questions or comments on that?

Alana Roberts: So I have a, I guess a sort of a, maybe a similar analogy to your thesis here is, uh, a while back I watched Peter Jackson’s, they shall never grow old. It’s a fabulous World War I documentary. And I wonder if there’s a connection between the lost generation, right?

These men that were just killed in mass numbers and early racing where they almost became sort of desensitized to death.

Skip McGoun: You’re referring to the post World War I?

Alana Roberts: Yes. Yeah.

Skip McGoun: Uh, yeah. Actually, I had studied the history of Bentley and how Bentley got started. Bentley was building cars for World War I aviators.

Okay, because they were the people from the gentleman sportsman segment at the time. He was building cars for them and they were engaged in as closely as they could to what they felt during World War I. Although it turned out, of course, a lot of people ended up [00:21:00] putting really heavy his Dan bodies on his automobile.

So kind of created like a, like a. Puzzle in terms of what a Bentley really was, but this was who Bentley was building vehicles for. It was it. You’re right. It was the same thing was the racing.

Audience Q&A: You mentioned nationalism, the desire for people in England, France, Germany, to have a car they could take pride in.

So with that in mind, wouldn’t the governments, even though their resources were stretched and limited, and especially when you look at your opening pictures of people in despair, wouldn’t those governments wanna fund events that would give them hope and excitement and a reason to be excited instead of just living in a pile of rubble?

Skip McGoun: I don’t know enough about the original situations in each of those countries, but I agree with you a lot of. Research can be done on the direct and indirect support. I tend to think at the time, and this is just [00:22:00] off the top of my head, governments didn’t have a lot of resources. They had run up considerable debts during the war.

Sure. It was tough. It was maybe, I suppose, moral support in a way. If they could ease up on regulations or maybe make sure that supplies one thing, were available for something else, whatever they could do that didn’t

Audience Q&A: cost anything. Even if they could clear the streets to a lap race to go through a particular,

Skip McGoun: but I suspect that this was definitely happening in Italy and there were only hints.

Of it happening in Britain of a governmental connection? Well, as and Zo Ferrari said, so much of this stuff is under the table and it’s really, really difficult to find information as to what really went on from this political and and economic standpoint. I think it’d be a great opportunity for someone in scholarship and people are kind of, it’s just nibbling around the edges.

Crew Chief Eric: Anyone else have any questions? There’s a comment from John Summers dovetailing off what you said. [00:23:00] He said, Sterling Moss’s success was in part reverence in Britain is down to the idea of Britain winning abroad and then taking your mind off of the reign and the poverty and everything that was going on at home.

So I guess to your point about nationalization and patriotism and all those things, so he just wanted to throw that out there to be in concert with what you’re saying.

Skip McGoun: Well that, and I know that the British automobile industry after World War II was highly expert oriented to earn foreign exchange. You know, the government was encouraging companies to produce the automobiles that could be sold in the United States to earn money.

Luke Chennell: I wanted to ask a question about your concept of entrepreneurial capitalism versus national capitalism, and in particular, I’m interested, I think, in how that manifests in the United States. And if you’ve thought through the post-war dimensions of construction of special automobiles in the United States and how that differs or is similar to the British perspective, the

Skip McGoun: literature on that subject is like massive because it’s, this is not just automobiles.

[00:24:00] This is. Pretty much across the board. A lot of it had to do with the way capital is allocated in the different areas. And in Britain and the United States, companies would raise money, presumably at arms length from capital markets, which is today. We still see that stock ownership being much more common in the United States and Britain, whereas.

On the continent, financing generally went through banks with close relationships to industrial combines. Just for one example, in Germany, they’re doing everything they can to try to get people used to the idea of investing in stocks and having a better investor connection with the companies as opposed to the companies being connected to the larger banks.

In fact, they designed the stock exchange to make it look exciting. If you ever get a chance to go to Frankfurt and go to the stock exchange, well worth the visit all for show, but that’s the reason behind it. [00:25:00]

Audience Q&A: This may be related, it’s somehow connected to what you’re talking about, but I had read somewhere along the line that one of the reasons death was tolerated so much in auto racing was that.

People were looking to replace their World War II heroes, which often were killed in plane crashes and fighter pilots and so forth. That auto racing became that outlet for a hero. And yes, it was high risk and it often included death, but it was accepted. But that. How those heroes were formed and are made,

Skip McGoun: and it was the vicarious thrill of imagining that was you.

I’d

Crew Chief Brad: have to disagree with that. I don’t think anyone goes to the fact to see people fail in,

Skip McGoun: oh, no. Uhuh. No, I’m not saying that. It’s just the idea of going to the track to feel as if you’re the hero. You’re driving fast. Being on the edge. Yes. Yeah, that’s that part.

Audience Q&A: There were so many drivers killed.

Skip McGoun: Oh no.

I started, [00:26:00] no, I completely agree with you on that, that that was not, the

Audience Q&A: tolerance was there for period, and I’m not suggesting that either, but I just was an interesting concept that I read and I just think, yeah, sometimes still. Yeah. Is that possible?

Lyn St. James: I’m just gonna question your flow chart. Yeah, all, all of the arrows went, the money went to the drivers and I don’t think that was true.

Pardon? I said the flow chart that you put up, all of the arrows went to the drivers. Like they were the ones getting the money. And I don’t think that’s true.

Skip McGoun: The air, no. The arrow simply means they got something.

Lyn St. James: Yeah. Maybe, you know, I’ve talked to even the ones that did survive, they might

Skip McGoun: have gotten something, although, you know.

That did change over time. Yeah.

Lyn St. James: Well, and many times they were, they were the sources many times as well. When you go back, even in post World War ii, the, the wealthy, you know, sporting gentlemen were the sources of some that money. But anyway, I just was commenting ’cause it was like, no, that’s not true. [00:27:00] Not a whole lot.

Well, and the other thing I’m just as a personal experience that when I went to Bonneville in 2017, I was just really amazed at the bottle of Salt Flats. That, and, and of course this is. Will passed post World War, but how many of the people that run and build cars and run at Bonneville were ex-military?

I mean, they almost all talked about that. And I mean, it was a real act, you know, an activity that the military was a, this was a place for them to go racing and, and to use their skills and have fun and, and camaraderie and all of that. So it was a culture that really attracted, uh, military people. Mm-hmm.

Just share that

Kip Zeiter: actually, a lot of the Bonneville cars were, yeah. Great analogy. Anyone else have any other questions? Thank you, skip. That was great.

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports [00:28:00] spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers. Race series and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding [00:29:00] of motorized wheeled land transportation.

Through the modern age and into the future. For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.[00:30:00]

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Post-War Racing Revival

- 01:18 The State of Europe Post-WWII; Early Post-War Races

- 03:28 The Constructors: Britain vs. The Continent

- 05:29 Financial and Material Resources

- 13:14 The Influence of Nationalism and Sentiment

- 15:34 Adrenaline and the Need for Speed

- 18:53 Conclusion, Reflections and Q&A Session

- 27:48 Closing Remarks and Credits

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

Post‑war racing wasn’t exactly a thriving business. Most teams relied on Handouts from wealthy patrons, industrial backers, or sympathetic corporations. Sponsorships that were as much about goodwill and prestige as measurable marketing returns. Promoters – often clubs or regional organizations — who staged events more for community spirit than profit.

Material shortages were eased by wartime leftovers: surplus airfields became racetracks, scrap metal became chassis, and mechanical know‑how was abundant thanks to military service.

So why Race at all?

The “how” of post‑war racing is intriguing, but the “why” is even more revealing. Skip argues that racing wasn’t about returning to normal — it was about continuing the intensity of wartime life. War had created a mechanically skilled population – veterans who could build, fix, and innovate with “a taste for speed and noise“ (the fast and loud thrill of combat). And as he puts it, an “Adrenaline addiction“ – a craving for danger and excitement that peacetime jobs couldn’t satisfy.

Nationalism also played a role. Italy wanted Ferraris on the grid. Britain wanted to see Union Jacks in the winner’s circle. Even cash‑strapped governments found ways – sometimes quietly – to support racing as a symbol of resilience and prestige.

For many, racing was the closest they could get to the camaraderie, risk, and purpose they’d known in uniform. It was, in Skip’s words, a way to relive “the best years of their lives.” In the end, post‑war racing wasn’t just about cars. It was about identity, belonging, and the human need to chase something bigger – and faster – than ourselves.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)