For a sport that now epitomizes cutting-edge safety, Formula One’s relationship with seat belts was shockingly slow to start. It wasn’t until 1972 that the FIA mandated their use – nearly two decades after American racers had already embraced harnesses as standard gear. So how did the world’s most elite racing series lag so far behind? And who finally changed the game?

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

From the dawn of road racing, European drivers clung to a dangerous belief: in a crash, it was better to be thrown clear than strapped in. This philosophy, famously practiced by American driver Maston Gregory, saw racers leap from cockpits like fighter pilots bailing out. But the data – and the carnage – told a different story.

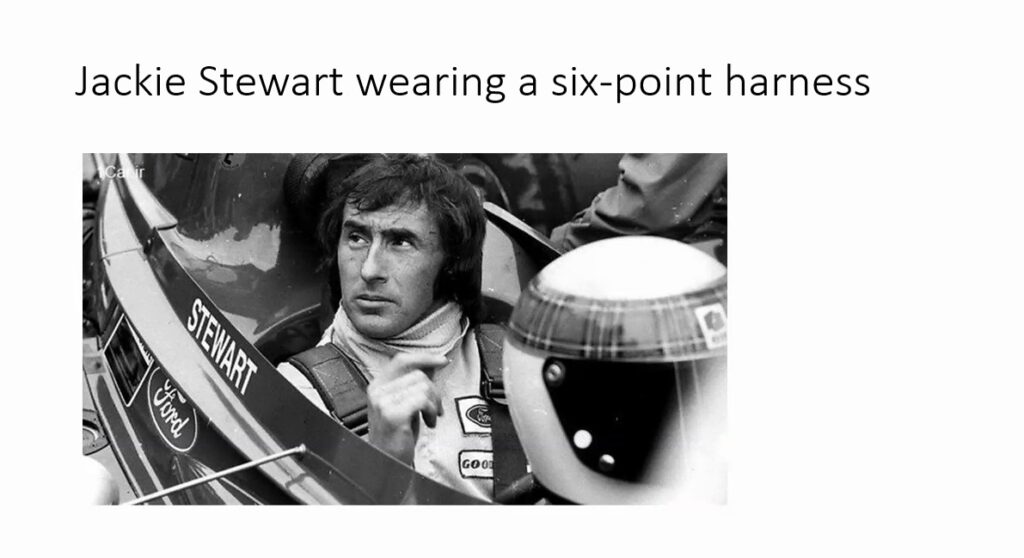

Enter Dr. Michael Henderson, a British physician with a passion for motorsport and a background in aviation medicine. In the 1960s, Henderson began applying crash science from the Royal Air Force to race cars. He fitted his own vehicles with four-point harnesses and later added an anti-submarine strap inspired by parachute rigs. His work laid the foundation for the six-point harness – a design that would eventually become the gold standard in racing safety.

Bio

Preston Lerner is a freelance writer who has covered racing for the past four decades. For many years, he was a regular contributor to Automobile Magazine and Road & Track. Lerner is also the author or co-author of six books, most recently Shelby American: The Renegades Who Built the Cars, Won the Races, and Lived the Legend. The material used in “Television Turns Its Gaze on Motorsports” is drawn from his upcoming book, The Deadliest Decade, which examines the safety, commercial and technological developments that transformed racing from 1964 to 1973.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, our History of Motorsport series, explores the delayed adoption of seat belts in Formula One racing. Preston Lerner discusses the late 1960s and early 1970s safety measures, focusing on Dr. Michael Henderson’s role in debunking the myth that escaping a crash unbelted was safer. Henderson’s innovative six-point harness design, inspired by aviation, eventually led to universal adoption despite initial resistance from top drivers like Jimmy Clark. The narrative also covers the political and technological barriers to safety improvements in racing, concluding with the tragic deaths that underscored the need for regulatory change.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

[00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsport Series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer Family

Seat Belts belatedly. Come to Formula One by Preston Lerner. For the past half century, the FIA has been the principal driver behind efforts to make racing safer. It wasn’t always so, although the SCCA required seat belts in 1957, the FIA didn’t follow suit until 1972 From the dawn of road racing, conventional wisdom held the drivers should jump out of the cockpit when a crash was imminent.

A technique perfected by Maston Gregory. This myth was conclusively exploded by a largely forgotten British physician by the name of Michael Henderson, who conducted crash investigations for the RAF. In 1968. Henderson, who Mood lighted as a club racer and freelance journalist wrote Motor Racing and Safety, the foundational text on this subject.

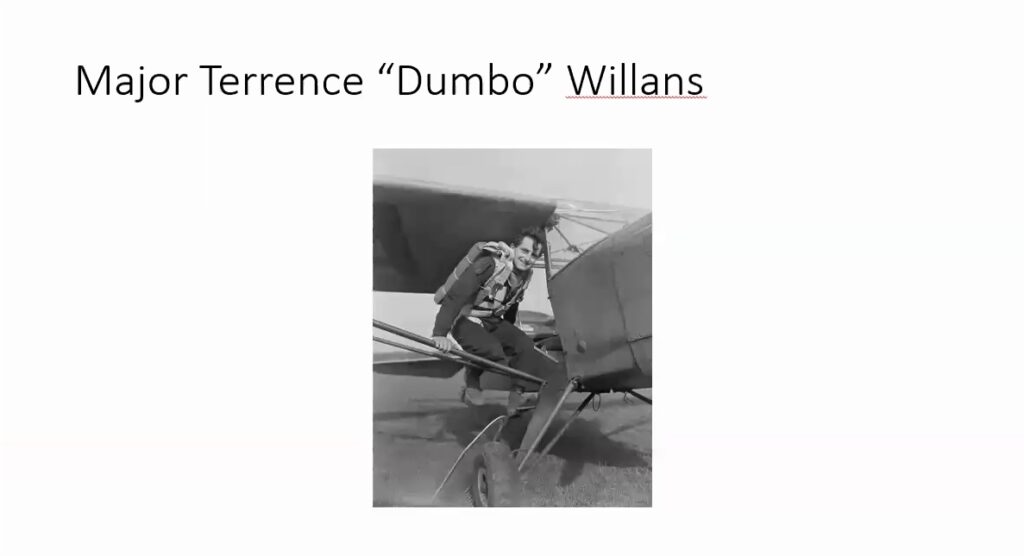

At the same time, he fitted his [00:01:00] own race cars with four point harnesses, augmented with an anti-submarine strap, inspired by a parachute design. This, put him in touch with Terrence Dumbo Willans, a record setting Parachutist, who tested ejection seats for the RAF Willans. Later went into business with another club racer, John Ning.

By 19 69, 6 point Willans harnesses were found in almost every car on the F1 grid. The battle for seat belts had been won almost before it started. Preston Lerner is a freelance writer who has covered racing and many other subjects for the past four decades. For many years, he was a regular contributor to Automobile Magazine and Road and Track.

Mr. Lerner is also the author and co-author of six books. Most recently, Shelby American, the Renegades, who built the cars, won the races and lived the legend. The material used in television turns its gaze on motor sports, is drawn from his upcoming book, the Deadliest Decade, which will examine the safety commercial and technological developments that transform racing from 1964 to 1973.

So today I will be speaking [00:02:00] about how Formula One. Finally, belatedly accepted seat belt. May find this hard to believe considering the status of Formula One these days, but seat belts were not commonplace in Formula One until late 1960s. They weren’t required until 1972. Now, this is long after they were standard equipment here in the United States.

This is a j Foyt in a Dirt Champ car in 1964. You can see pretty clearly here that he’s wearing shoulder harnesses. And in fact, in 1968, seat belts were required in all American passenger cars, yet they were not in almost any Formula One cars at the time. And there’s a strange story behind this, which I’m going to tell here today.

I think most people would agree that these days, formula One is considered the pinnacle of motor sports. It’s the most expensive form of racing. Uses the most exotic technology and it has, I think, the most enviable safety record. Since 1994, only one driver has been killed in a Formula One race, and this is largely because of the safety [00:03:00] protocols and technology that the FIA has adopted, and they deserve a lot of credit for making racing an incredibly safe sport.

This was not always the case. You go back to the fifties, sixties, and into the seventies where the one cars were among the most lethal vehicles on the planet. Ersonal once told me one time I had a one in three chance of dying. Emerson was a two time world champion, two time IndyCar champion, 9,500 winner.

Very charismatic figure. When he told me this, I thought he was exaggerating, to be honest. But I went back and looked at the records and in his fourth Formula one race at Monza in 19 70, 27, drivers participated in practice. Nine of them later died in race cars. Now it’s true they didn’t all die in Formula One cars.

If you look at the years 1964 to 1973, and that’s the period that I’m studying, 10 drivers died in Formula One races in that 10 year period. So a pretty appalling safety record. Some of you may recall Peter [00:04:00] Bryant best known for designing and building Can-Am cars, but earlier in his career, he worked, this is in the mid sixties, worked on Formula One cars and worked in Indy cars.

And of that experience, he said, compared with the contemporary Indy cars. F1 cars were death traps. Bobby Unter three time Incar champion Indy 500 winner. That is, I was even more skating in his assessment based on his experience driving A BRM in the Canadian Grand Prix in 1968. He said in those days, formula One was way behind IndyCar, racing way behind.

Their technologies weren’t up with ours. Safety was, I ventured to say, 10 years behind. In those days, they used to kill drivers like popped popcorn. Uncle Bobby had a unique turn of phrase. I would say there were a couple of factors at play here. The most obvious and probably most important was technology.

1966, formula One regulations changed from a maximum of 1.5 liters to three liters. So engines doubled in size and uh, speeds went up, [00:05:00] I don’t know, 30, 40 miles an hour. This is also the period when wings and downforce first appear. There was also a, uh, tire war going on between Firestone, Goodyear, and Dunlop.

And during war, that’s when technology advances exponentially. So it was with tires. Tires became much wider. They became lower profile. They were much stickier. This is when the slick tire, the tread tire, was invented, at least for road racing. So cornering speeds went up dramatically. And corners are, of course, where the most serious accidents occur.

And you have to remember that in this period. The road courses in Europe were largely just that they were road courses, runoff areas had things like trees and telephone poles, sometimes farmhouses and barns and things you did not want to hit at high speed, and when you did hit them, the results were often fatal.

Second factor in explaining this appalling safety record was the attitudes of the era. Yes. When a driver was killed, there was naturally a period of mourning and grief, but the [00:06:00] general consensus at the time was. This came with the territory and it was sort of the cost of doing business. You have to remember that 1960s were only one generation removed from World War ii, a global conflict, and when something like 50 million people died, many of them civilians.

So when a young man who was doing something voluntarily without a gun being put to his head doing something, in fact, that a lot of the fans wish they were doing himself when he was killed in a race car. Yes, people were sad, but it didn’t spark outrage the way it would do. Now, another factor is that in those days, danger was considered part and parcel of the sport it was, or the appeal of the sport.

It was what made the sport special and distinguished it from stick and ball sports like baseball, football, and basketball. This was a philosophy that was adopted not just by fans and journalists, but by many of the drivers themselves. So, uh, you have to, that needs to be accounted for. Third factor was politics.

In those days, the hierarchy [00:07:00] of racing was very strictly delineated. At the top of the totem pole were the Blue Bloods, the aristocratic members of the Old Boy network who ran the National Sporting Clubs, these were the people who made up the directors of the CSI, which was the competition arm of the FIA back then, and they ran the put on the races that made up the Formula One schedule.

The middle class was represented by instructors and vendors. Guys like Mike Len and Colin Chapman, and they were, you know, the equivalent of the shopkeepers. The small shopkeepers are entrepreneurs of the day, clever guys to be sure, but, you know, involved in the, the grubby endeavor of making a living. The drivers were a level below them, and they were analogous, I guess, to plumbers and electricians.

They were people with special skills and they were compensated for them. In the case of superstars like Sterling Moss and Jimmy Clark, they were compensated very well. But by and large, they were considered to be interchangeable cogs in the machine. And when it came to safety, the aristocrats who ran the sport [00:08:00] didn’t see a moral case for safety.

And as a practical matter, they realized it would cost a small fortune, well, actually a, a large fortune to, to line racetracks with miles of guardrails to equip and train firefighters and to hire medical staff and outfit hospitals. I mean, this would cost a lot of money, and there wasn’t a lot of money in racing in those days.

There’s no real big time sponsorship before, uh, lucrative television contracts. So the money was gonna come out of their pockets, and they had no intention of spending it to keep a couple of drivers from getting killed. The constructor didn’t object to safety per se, but for them, as a practical matter, making course safer would take time.

It would cost money, probably add weight. Added weight means slower lap times, and slower Lap times is exactly what you don’t want if you’re a constructor. So as far as they were concerned, the only way they were going to implement any sort of safety upgrades into their cars is if it was required by the regulations.

The only group with a vested interest in safety were the drivers, and they were [00:09:00] the ones that had no leverage. And so nothing really happened on that front. This can be seen very clearly in the rules that the FIA promulgated regarding safety during this period. I mean, there are so measly as to be almost non-existent, a couple of red letter dates, and so 1952.

Helmets are required. Good thing. The problem is the only helmets into the sixties that is were there glorified paper mache, which had been designed originally for British colonial administrators, and then there were sort of the cork helmets that had been designed for polo players. Phil Hill once set about his helmet that he called his helmet a uh, a cardboard hat.

The point being that it really didn’t do much to protect dryer from head injuries in the case of an accident. 1961, the FIA required roll bars. What they didn’t do was require roll bars that were tall enough or robust enough to actually protect the driver in the case of a rollover accident, apocryphal stories about guys making roll bars out of wood and painting them to look like [00:10:00] metal.

And it said that Colin Chapman told his mechanics never push a car around the paddock by the roll bar. Point being that they were so flimsy as to. Really not be worth what they weighed. 1963, the FAA required fire retardant uniforms. And again, this sounds like another step in the right direction except for the inconvenient fact that Gen Nomex wasn’t yet commercially available and there was no fire retardant material out there for drivers to use.

While there was actually an aluminized, things that firefighters were aware, but this was not practical for drivers. So they were the normal cotton uniforms. And what they would do is they would soak it in a. Solution of boric acid, which supposedly added a couple of seconds of, of flame protection.

Basically, these suits were as valuable in a fire as the helmets were in the case of a crash. And in 1964, the FIA promulgated regulations governing the installation of seat belts, again, a good thing. Unfortunately, what they didn’t do is require seat belts. So as a result, nobody installed seat [00:11:00] belts, the first team to show up with seat belts.

The operation outta Southern California, this was an All American team, and the reason why they had seat belts is they drew their inspiration, not from Formula One, but from Indy, where everyone was already using seat belts. SCS looked beautiful, but they were dogs slow. And when they debuted at Monaco, they were so far off the pace that prevent.

Lo asked Sterling Moss if he would take a spin in the car and see if he could figure out what the problem was. Moss agreed and he gets over to the car, he looks in the cockpit, sees the seat belt, and what does he do? Doesn’t put ’em on. He sits on top of them and he goes down. And this was very much par for the course back in the day Formula, the one that is.

As if people didn’t understand what seat belts were. They’d been around supposedly since the middle of 19th century when they were used on gliders. And 1911, when the Wright brothers delivered one of their first airplanes to the US Army, it was equipped with a leather restraint. By 1928, all American planes had to have be equipped with seat belts.

And during World War ii, [00:12:00] all American combat pilots wore four point harnesses. So. Two lap belts, two shoulder belts. Took a little while for seat belts to get to the car. World. Nash was the first manufacturer to offer seat belts as an option. This is 1949 and in 1951, seat belts became available as an aftermarket item, but the real red letter date for seat belts is 1959, and that’s when Neils Boland, who was the chief safety engineer at Volvo, patented the three point seatbelt.

This almost immediately became the industry standard. And in 19 68, 3 point seat belts were required on all American passenger cars. Racers took a little longer to get with the program, so to speak. Supposedly Barney Oldfield put seat belts on a race car in 1922. That’s what I read. Can’t really find any confirmation of that.

And. At that point, uh, Barney would’ve been pretty old and longer than than two, so I’m not sure what sort of race car he would’ve been racing back then. But after World War ii, seat belts became commonplace. Worst surplus harnesses were available and they were [00:13:00] bought up and used by drivers in Indy cars and sprint cars.

Midgets stock cars Dragsters 1954. The SECA required seat belts in all of its cars competing in races. And that included even the Pist, sprites and Crosley Hotshots. So by the 1960s, basically every serious driver in the United States would be using a seatbelt, not so over in Europe. In fact, well, until the sixties.

Most road races thought in Europe, thought that seat belts were dangerous rather than a benefit. Conventional wisdom was that given the opportunity you were supposed to jump outta the cockpit before an accident, more or less like a, uh, a pilot bailing out of a stricken airplane. Richard Atwood, who won Lamont 1971 and a P nine 17, told me we all knew the cars were deformed in the case of a crash.

That’s why belts weren’t really thought of as being a particularly good idea, especially if the car caught fire. The most accomplished practitioner of bailing out of a race car before an accident was American [00:14:00] Maed Gregory, who famously leapt out of a lister jag at Silverstone in 58, and then he did it again at Goodwood the next year in a, um, Turro Jaguar.

Peter Bryant tells a funny story about Gregory a couple of years later, before the Tasman series, he was doing a seat fitting with Masterton Gregory. So they’re in the garage and Gregory’s in the cockpit. Everything’s kinda low key, and then all of a sudden Gregory jumps up. Pulls himself outta the cockpit, onto the floor of the garage, and Brian thinks something’s wrong.

Maybe the car’s on fire. And he goes, what’s going on? Gregory calmly stuck a stick of red licorice in his mouth. And don’t worry, I always check out the escape route when I drive a different car. As you might imagine, a lot of unbelted drivers flew out of their cars unintentionally over in Europe.

Probably the most famous incident. You may have seen this photo, a pretty well known photo of Hans Herman watching his BRM Bavel roll at ous after he’s been ejected from the cockpit. Now, fortunately, Herman wasn’t hurt in this accident, but this was very much the exception rather than the rule. Mos learned this [00:15:00] lesson the hard way a.

At Monaco was thrown out of cockpit of his Lotus at SPA Grievously. Injured at RAN in 1964. Team Lotus Driver Peter run’s career ended when he was thrown outta the cockpit. Jean Pierre s for permanent injuries to his left arm, 1965. John Serty motorcycle champion broke his pelvis and several other bones when he was half thrown out of the cockpit of his Lola T 70 of most sport.

He wasn’t wearing a seatbelt and Lucky Kassner wasn’t wearing a seatbelt, was killed. A couple months later during the LAMA test, Kassner was actually driving a Maserati coup, so he was thrown out of the cockpit of a a closed cockpit car, which gives you some idea of the forces that were involved in these crashes.

The stories of how seat belts finally came to Formula One has rarely been told, and it stars a, an unlikely and largely unknown hero In the name of a young British physician, Dr. Michael Henderson, he was a hardcore racing fan While he was in medical school, he worked as a track [00:16:00] announcer and he wrote freelance articles for car magazines 1960, he managed to, uh, go club racing in a Lotus seven that he caged at a Colin Chapman.

When he, uh, earned his medical degree, he went to work for the Royal Air Force Study in Aviation medicine area. And when he started doing that, he, he made a surprising discovery. He realized that the aviation industry had been studying high speed accidents for decades, and in fact, they had a whole all sorts of protocols for how to minimize accidents that resulted from high speed crashes.

And as he told me. I began to understand that there was a science of vehicle safety out there that we didn’t have to ignore the fact that people are getting injured in racing accidents any more than you would ignore any other kind of melody realms. The aviation medicine textbook that we were using at the time was about three inches thick.

It was a major book, and yet nothing had been done to adopt any of this material. Psychological, physiological impact, resistance, anything to motor racing. Henderson was no dummy, so he decided to [00:17:00] apply some of what he learned to his own racing. Uh, when he went, ran a touring car at the, at the Berg ring, he fitted it with a three point belt and he said, did the same thing with his street car, which was a Jaar XK 1 20 19 66.

He bought a Malick U2 Clubman and his plan was to put in a four point harness, like the ones he used by RAF pilots he worked with. But he realized pretty quickly that the lay down seating position, which is very similar to a a formula car. Meant that in the case of a funnel collision, he would slide under the belts as a submarine under them and he could be grievously injured.

So his state, what happened, he had trained as a parachute, and it struck him that the crotch restraints in a military parachute might be able to be adapted to a four point harness to provide anti-submarine protection. So he went to a company called Britax, which was then in the seatbelt business. It’s now in the car seat business, and he convinced them to build a harness to his specifications, perhaps looped around his thighs.

To provide the anti submarine protection. And this created the first six point harness used in road racing competition. [00:18:00] Angels should have been singing and, uh, trumpets blaring. Instead, there was silence. So to draw up some publicity, Henderson wrote a couple of articles and these generated nothing more than, uh, polite indifference.

So he now embarked on plan C, and he contacted various British racing organizations and he persuaded them. To agree to send him information about all the accidents that occurred in the upcoming season. His idea was to collect all this data, kind of crunch it, and then, um, write a book about his findings.

That’s exactly what he did. Wrote the book in 67, published it in 1968. Motor Racing and Safety is the foundational text of the Motorsport Safety Movement. Drawing on his analysis of more than 200 accidents, Henderson comprehensively demolished the myth. It made sense to jump out of a moving race car and he made the affirmative case for wearing a seat belt dad gravitas to his thesis and also to get more people to buy his book.

He decided to get a luminary, someone luminary in the [00:19:00] motor sports world to write the forward, and he approached Lewis Stanley who ran the Formula One team. And Stanley was a somewhat controversial figure, always dressed in blue blazers and gray flannel sax. He was somewhat pompous, could be a bit pretentious.

Critics considered him the Colonel Blimp. The motorsports world. On the other hand, he was just about the only member of the aristocrats who ran racing, who believed in safety, and he’d almost single-handedly created the international ground pre-medical service, which provided a well-equipped mobile hospital that, uh, went from track to track Henderson pitches.

Stanley Stanley invites him to come to his estate. New Cambridge Henderson shows up, gives him a spiel about seat belts, and when he gets finished, suddenly goes right. I agree. I’ll put belts in Jackie Stewart’s car. By this time, Henderson was dissatisfied with the locking mechanism that Britax was using for the six point harness as fate would have it.

He was working on a program at the time to upgrade the seat belts and the F four phantoms that the RAF was buying from McDonald Douglas. This had put him in touch with the GQ [00:20:00] Parachute company, which had provided all the parachutes used by the RA during the Second World War. Henderson asked GQ if they might create a six point harness for him, and they advised him to get in touch with their chief consultant.

Major Terrence Willens. Now Willens is one truly remarkable, remarkable character. Not so much for his racing stuff, but just for his entire career. Orphaned at 13, he worked as a Bronco buster, as a teenager, while he was still in his teens. When, uh, world War II erupted, he volunteered for the British Calvary and trained as a paratrooper.

Before his first jump, his instructor yelled, uncurl, your ears Dumbo and fly. Willens he was for the rest of his life. He served as a so-called Pathfinder during the war landing behind enemy lines in France, Greece, and Italy. After the war, he performed a series of incredibly risky high altitude tests and eventually became known as the father of British Sport Para.

He performed the first live fire ejection seat tests of the fallen net jet fighter. He wing walked without a parachute of ear [00:21:00] shows, and he also worked as a motion pitcher, stuntman. So Willans and Henderson collaborated to create the six point harness that GQ and manufactured and made available to Formula One drivers at the start of the 68 season.

Several of them had read Henderson’s book and they were what, I guess you’d call seatbelt curious. The major holdout, unfortunately, was the best known driver in Formula One. That was Jimmy Clark, two ton world champion. Jimmy absolutely refused to wear a belt. Henderson recalls, and this is kind of weird, I don’t really understand this, because when Clark raced in Indy 500, he had to wear a belt.

It was required. By usac, and so he was wearing seat belts when he won the 500 in 1965, but he refused to put them in his Formula One car, and he wasn’t wearing them in the Formula two car. He was racing in Hockenheim on April 7th, 1968. This was a dreadful, dreary weekend. It was rainy Clark’s cars. Lotus had a misfire.

He was running mid-pack early in the race tire deflated. Got into a terrible tank. Slapper couldn’t control [00:22:00] it. Car hit the tree at high speed. He was thrown outta the cockpit and his head slammed against the trunk of the tree. About 10 to 12 feet up, killed instantly. This was pretty much a come to Jesus moment for Clark’s colleagues.

Chris Aon, who was uh, the number one driver in the Ferrari team said, speaking for many of his colleagues. Jimmy’s death was the most profound thing that had happened to me in my recent career because I felt if it could happen to him, what chance did the rest of us have had to confess? I don’t think seat belts would’ve saved.

Jimmy Clark Chenbo accident was just too violent. On the other hand, drivers didn’t have access to any other sort of driver equipment. I mean, it was either seat belts or was nothing. So during the course of the 68 season, many drivers, most drivers, adopted and started wearing seat belts. As Henderson told me, it confirmed my belief that human beings are sentient creatures if given the right information.

They understand that there are reasonable things to do anyway. Interest in seat belts naturally filtered down to less exalted forms of racing. John Finning was an early convert. He had been one of the more successful [00:23:00] British Formula three drivers early in the sixties before retiring. 19 60, 80, he wanted to get back into racing on an amateur basis, do some hill climbing.

And his wife agreed to allow him to do so, only if he invested in the latest in safety gear. So he bought a, um, a Nomex suit, which was available at then end. He bought a, uh, full face helmet, which was available by then, and he wanted to buy some seat belts. But it wasn’t like you could go to Pegasus or your local race shop and pick up a pair of, uh, racing belts.

They, they weren’t available. So. The only guy he knew who was wearing seat belts was his old F three rival Jackie Stewart. So Fing called BRM, found whose supplier was they put him in touch with GQ and GQ put him in touch with Dumbo Wills. Willin met with fending when he was in the area, performing some ejection seat tests.

Fending bought a four point harness and installed it in his hill climb car. Fending had a race shop, that’s what he did for a living. And so people would come over and they would look at his car and they’d, uh, look inside the cockpit and go, Hey, what’s that stuff there? Seat belts. And a couple of people said, well, that sounds like a pretty good idea.

I mean, we should, maybe I should be wearing seat belts. So [00:24:00] fitting, started selling seat belts and after about six months. He went to Willans and said, Dumbo, did you ever think of doing this professionally and stop trying to kill yourself? Jumping out airplanes I him into forming a company. He was the brains and I was the salesman manufacturing.

Became the first major player in the racing market and its signature. Royal Blue Belts could be seen in virtually every F1 car of the Euro. You can still see a lot. I mean, will is still in business and you can still see a lot of them today. It’s their favorites in uh, uh, restored F1 cars that are vintage racing, especially cars of the DFE era.

Very, very popular and very good. By this time, ironically, Dr. Henderson had sort of gotten out of the seatbelt business. Well, he was never really in the business, but he sort of got outta that world. He moved to Australia and embarked on a new and fruitful career in road car safety, and he eventually served as director of Traffic Safety in New South Wales.

But he kept in touch with his old racing pals. And so in, uh, January 69 Formula, the one drivers, several of them came over to race in at Taman series in Australia. He had dinner with Jochen rent. [00:25:00] Was a hard nosed Austrian who’d more or less taken Clark’s place as the number one driver on the Lotus team.

And after Jimmy Clark, he was probably the most vocal advocate for safety. During this era, he was a big believer in what Henderson preaching and he told Henderson, I’ve read your book and I agree with everything you say, but you will never get me wearing crotch belts believe that in the case of an accident, the thigh belts, the crotch belts would crush his private parts, which would be very painful if in fact that was the case.

But Henderson explained that’s not what the way they worked. But, uh, Ridge couldn’t be convinced and so he continued to race with a four point harness, did not have the crash builds with anti-submarine protection. To September 5th, 1970 practice for the Italian Grand Prix Monza rent coming off four consecutive victories in the summer in the groundbreaking Lotus 72 there Monza in practice, he had just blown past any human, about 190 miles an hour, and in the brake zone for the parabolic at his car, suddenly viewed to the left and ran it to a guardrail.

Had the [00:26:00] guardrail been stored properly, it wouldn’t have been a terrible accident. Well, it might have been a bad accident, but it wouldn’t have been a fatal accident. That’s for sure. Uh, unfortunately, the guardrail was not installed properly. The bottom strand gave way. The wedge nose of the Lotus 72 dug in underneath it and it came to an immediate stop.

Rin was thrust forward in the cockpit, and since he wasn’t wearing a submarine belt, he slid forward and the belt buckle severed his jugular vein. He was dead before medical attention could. Later that year, rent became the first driver ever. World driving champion. Despite. The FIA didn’t take action to require six point harnesses.

In fact, they didn’t require seat belts at all, which is a dereliction of duty. That’s a little hard to understand. I mean, you didn’t have to be a safety advocate to understand seat belts made a lot of sense. 1969, British privateer, John Wolf was killed on the first lap of the 24 hours of LAMA when he crashed without wearing seat belts in his Porsche.

Nine 17 a week before [00:27:00] rent was killed at Mona British Amateur, Chris Summers. Who wore street clothes when he raced and refused to wear a harness, died when he was thrown from the cockpit of his Lola T 1 72, in a formula of 5,000 race at Ston. Almost exactly a year later, his friend and fellow 5,000 racer Peter Houghton, who likewise wore street clothes when he raced and didn’t wear seat belts, died when he was ejected from the cockpit of his Cooper T 90 at Ton Park.

It wasn’t until 19 72, 19 72 that the f. Belatedly mandated six point harnesses long after the vast majority of formula cars were already out with them. How many drivers have been badly hurt or killed needlessly before action was taken too many. The lesson to be learned from the history of seat belt is clear.

If racing was to be made safer, the changes wouldn’t come from the top down. They would be forced on the sport from the bottom up by the people whose lives were at risk, which made sense. After all, revolutions are won on the battlefield, not in the boardroom. [00:28:00] Thanks for tuning in. Really appreciate it.

Thanks also to Duke Inger, Bob Barr and the rest of the crew who put on this symposium. Tremendous amount of work goes into a project like this, and they deserve a huge pat on the back. Anyway, thank you very much. Take care.

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special [00:29:00] events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org. We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more [00:30:00] about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 The Early Days of Racing Safety

- 00:41 The Myth of Escaping the Cockpit

- 00:51 Michael Henderson’s Contributions

- 01:58 The Adoption of Seat Belts in Racing

- 02:39 Formula One’s Safety Evolution

- 04:50 Technological Advances and Safety

- 06:55 The Role of Politics in Racing Safety

- 21:44 The Tragic Deaths and Their Impact

- 28:00 Conclusion and Acknowledgements

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

Between 1964 and 1973, Formula One was a bloodbath. Ten drivers died in F1 races alone, and many more perished in other series. Emerson Fittipaldi once estimated a one-in-three chance of dying on track – a claim backed by grim statistics from his early races.

Technological leaps made cars faster but not safer. Engines doubled in size, tire wars pushed cornering speeds higher, and tracks remained lined with trees, poles, and buildings. Meanwhile, the sport’s aristocratic leadership balked at the cost of safety upgrades, and constructors resisted changes that added weight or complexity. Drivers – the ones with the most to lose – had the least power to demand change.

A Doctor, a Parachutist, and a Revolution

Henderson’s breakthrough came not just from science, but from collaboration. He teamed up with Major Terrence “Dumbo” Willans, a decorated paratrooper and stuntman who had tested ejection seats and pioneered British sport parachuting. Together, they developed a six-point harness that offered true anti-submarine protection.

Still, adoption was slow. Even racing legend Jim Clark refused to wear belts in his Formula One car, despite using them at the Indy 500. Tragically, Clark was killed in a Formula Two crash in 1968 – thrown from his car and fatally injured. His death shook the paddock. As Ferrari’s Chris Amon put it, “If it could happen to him, what chance did the rest of us have?” By the end of 1968, most F1 drivers had adopted seat belts voluntarily. But the FIA still didn’t require them.

From Tragedy to Transformation

The final turning point came in 1970, when Jochen Rindt – Clark’s successor at Lotus and a vocal safety advocate – died in a crash at Monza. His car submarined under a poorly installed guardrail, and the belt buckle severed his jugular vein. Rindt had refused to wear crotch straps, fearing injury to his groin. He became Formula One’s first posthumous world champion. Even then, the FIA delayed. It wasn’t until 1972 that six-point harnesses became mandatory.

Meanwhile, Henderson’s work inspired a grassroots movement. British club racer John Fennings, seeking safer gear for hill climbs, tracked down Willans and began selling belts from his race shop. The two eventually founded Willans Harnesses, whose royal blue belts became ubiquitous in F1 – and remain popular in vintage racing today.

Henderson moved to Australia and shifted focus to road safety, but his legacy in motorsport endures. His book, Motor Racing and Safety, remains a seminal text. And his belief – that informed people will choose safety – proved true, even in the high-octane world of Formula One.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)