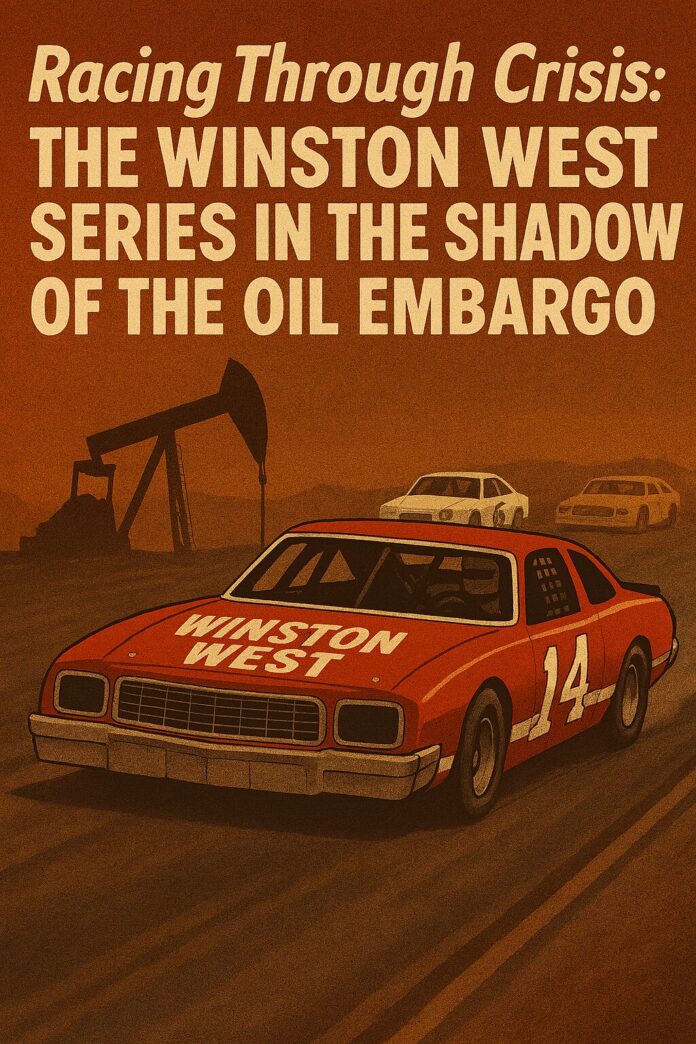

When the OPEC oil embargo struck in 1974, it rattled the foundations of American motorsport. Fuel shortages, canceled events, and shuttered tracks left fans and competitors wondering if racing itself might be banned – something not seen since World War II. Yet out of this uncertainty, resilience and reinvention defined the second half of the decade. Between 1975 and 1979, the NASCAR Winston West Series became a vivid stage for transformation, proving that regional racing could thrive even in turbulent times.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

The oil crisis forced shortened race weekends, abbreviated schedules, and permanent closures for many tracks. Environmental concerns, suburban sprawl, and noise debates added pressure. Yet, despite these challenges, regional divisions pressed forward. The Winston West Series, born from the Pacific Coast Late Model Division in the 1950s, carried the banner for West Coast stock car racing, offering fans continuity and drama when national racing seemed uncertain.

Bio

Daniel J. Simone earned his Ph.D. in American History from the University of Florida in 2009. From 2010-2015, Dr. Simone taught World History and Environmental History at Monmouth University. Curator of the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, North Carolina, and held that position through 2021. The following year, he was tabbed to assist the New York Historical Society Museum & Library, where he co-processed the Women’s Sports Foundation Collection and developed content for digital exhibition. Dr. Simone is on the editorial board of the Journal of Motorsport Culture & History and serves on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Voting Committee.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, our History of Motorsports Series, looks back at a transformative period in American motorsports during the mid-1970s to 1979, guided by Dr. Daniel J. Simone. The episode explores how the OPEC oil embargo challenged and eventually reshaped racing, focusing on the NASCAR Winston West Series. Various significant drivers, such as Ray Elder, Jimmy Insolo, and Herschel McGriff, are highlighted alongside the struggles and triumphs of west coast racing teams. The narrative also covers the impact of the environmental movement on racing and the importance of regional talents in shaping the national scene. The episode concludes with the legacies left by these drivers and the changes in racing dynamics heading into the 1980s.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

[00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports Series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer family.

On this episode of the Logbook re returned to the mid 1970s where American Motorsports faced one of its greatest challenges, the OPEC oil embargo. It had shaken the nation fueling fears that racing itself might be banned for the first time since World War II as the 1975 season, dawn competitors, fans, and industry leaders long for normalcy.

But what unfolded was anything but ordinary. By 1979, the sport had been reshaped in ways no one could have predicted new sanctioning structures, shifting venues and fresh pathways to reach audiences. The NASCAR Winston West Series captured this turbulent era with vivid fashion. A six time champion stepped away to tend the family farm.

While a lumberman who began racing in 1945 proved age was no barrier, a [00:01:00] journeyman Californian claimed his first championship at 41, then doubled down with another title. Just two years later, Canadian Stock Car Legends broke through and Riverside International Raceway became the stage for unforgettable drama, all in the fraction of a race.

Guiding us through this remarkable story is Dr. Daniel j Simone with a PhD in American history from the University of Florida. Dr. Simone has taught, curated and chronicled motorsports history at the highest levels. From his tenure as curator of the NASCAR Hall of Fame to his work with the New York Historical Society.

His scholarship and storytelling illuminate how the oil crisis and its aftermath forever altered the trajectory of racing in America. Today he brings us into the heart of an era defined by uncertainty, resilience, and transformation. Thanks again for having me. I spoke about West coast racing last year, and particularly about Ray Elder and the racing farmers and, and some of that ties into my topic for this year, mostly the Winston West Series and its history.

In the second half of the 1970s competitors, spectators, fans in the motorsports industry, from [00:02:00] the highest levels to the grassroots hoped normalcy would return to American Motor Sports at the start of the 1975 season. A year earlier, many feared automobile racing could be banned, as was the case after the American entry into World War II in 1974.

The OPEC oil embargo had a profound influence on sport, travel and recreation throughout the United States, and nearly all varieties of auto racing, American auto racing got through the first half of the season with abbreviated competition. Weekends, shortened races, canceled events, and temporary, or in some instances, permanent track closures.

To be sure the 1974 auto racing season was like no other season before since the oil embargo did force some to reconsider motor sports and its place in the environment, a growing citizen-based environmental consciousness, suburban sprawl, highway construction, noise pollution, and other factors. Put motor sports more on the defensive.

Nationwide, many track owners and operators were permanently placed under a [00:03:00] great amount of strain. The signs were rather obvious and many did not quite know their days were numbered. But from 1975 to 1979, national racing entities as well as smaller regional series and divisions pressed on despite a rough decade for the American economy.

One regional series competing under a national banner was the NASCAR Winston West Series from 1975 through 1979. The division featured robust schedules with annual visits to many of the same facilities, a deep talent pool and memorable races. Going back to its early days in 19 54, 5 years after what is now known as the NASCAR Cup series was inaugurated.

The NASCAR Pacific Coast Late Model Division began competition teams and drivers in regionally and locally sponsored stock cars, competed mostly in California with occasional events in other Western states and British Columbia, Canada. During the 1950s Pacific Coast Division drivers did occasionally Venture East to race in NASCAR Cup, or as it was known then grad national [00:04:00] events beginning in 1959.

It was not uncommon for west coasts to trek all the way east of Florida to take a stab at qualifying for the Daytona 500. However, west Coast Racers did not have to journey across America if they wanted to pit their talents behind the wheel and in the garage against the Cup Series, hoping to spoil the efforts of cup regulars.

Riverside International Raceway, which first hosted races in 1957 became Southern California’s capital of American Auto Sport in the 1960s. Riverside was located about an hour’s drive east of Los Angeles and the then sparsely populated wine growing desert community of Moreno Valley. The track accommodated all forms of motor sports and attracted domestic and foreign competition, even hosting a Formula One race in 1960 and during the 1960s, NASCAR’s Top division visited Riverside twice a year.

There were a couple occasions where the Cup Series raced there three times in the season. The NASCAR Pacific Coast Late Model Division changed names a bunch of times. It became the NASCAR Grand National West Division for the 1970 season. RJ Reynolds Tobacco [00:05:00] company entered a sport in 1971 through its Winston brand, brought money and support to the Cup Series, but also to other divisions.

For a time it was known as the NASCAR Winston Western Grand National Series and eventually in the mid seventies, was referred to by its most famous moniker, the NASCAR Winston West Series. Perhaps no better place to start. A discussion of the 1975 Winston West season is with a brief mention of who was not on the track.

Jack McCoy concluded his driving career at the close of the 1974 Winston West season. The Modesto, California driver claimed two championships, one in 1966 and another in 1973. And is best remembered for being credited with 54 series victories. His indelible impact on the growth and development of the series cannot be quantified, not to be overlooked.

There was a second major series absence in 1975. Dick Bound quit his career behind the wheel after competing in the season to opener at Riverside in January, he won 14 races in the division and was one of the most popular [00:06:00] drivers to hail from the Pacific Northwest in the first decades of the series.

McCoy and Bound left behind a talented group of series regulars and young drivers. A few had aspirations of moving on to the Winston Cub series, but most maintained a focus commitment to excellence at the regional level, ensuring the series would remain vibrant for the second half of the decade. Ray Elder, one driver who hoped to race full-time at the national level, picked up championship number five in 1974, and few were willing to bet against the pride of Tiny Caruthers California and his quest for his sixth title in 1975.

Elder was still in his early thirties. And the racing farmers, his laser focused and loyal team of family and friends were up to the challenge after McCoy and bound hung up their helmets. Elder remained as the only longtime veteran of the series to compete on a full-time basis in 1975 as he sought a full-time ride in the Winston Cup series.

Elder was no stranger to Victory Lane in NASCAR’s Elite division. He defeated all of the cup drivers winning at Riverside in [00:07:00] 1971. And then winning again in the second Riverside race in 1972 and in 1975, elder made it a half a dozen Winston West Championships. Elder’s final title would be one of his finest.

He won five races, including his ninth and final triumph on the dirt at the legendary Ascot Park just outside of Los Angeles. Elder posted 14 top fives, finished on the lead lap 12 times, and was one of four drivers who competed in all 18 points paying content. Elder moved to the top of the points after a fifth place finish at Phoenix Arizona’s Manzanita Speedway in the third race of the season.

On May 10, later that year, the West Series returned to Manzanita for a second date. It was the final time the division competed at the legendary Phoenix facility. Perhaps most famous for its rich history of Wingless spring car racing. Although the Arizona State fairgrounds in Phoenix, which was paged in the early 1960s would absolutely require inclusion in the debate.

There is no more iconic dirt track in the valley, the Sun, and in the Grand Canyon state than Manzanita. And according to one of the [00:08:00] greatest contributors of our understanding and deep knowledge of track histories in both the US and Canada was the late Allen Brown who should be in every racing hall of fame in the United States.

By next year, Manzanita, which originally hosted dog races. Began hosting auto races in 1951, but the development of affordable air conditioning, the interstate highway system, and a growing baby boomer population led to massive growth in many small Sunbelt cities. Beginning in the 1950s, greater Phoenix has become one of the largest metropolitans areas in the United States.

The Manita properties sold for development in 2009. Many of the tracks once on the Winston West calendar throughout the seventies suffered similar, fades in the decades to come and are long gone today. And returning from this racetrack rabbit hole, elder won his 45th career race at Man cta, and it was his final Trump of the 1975 season for Elder.

The path towards championship number six was a little easier than some of the others, primarily because three of the biggest names in Western racing at the time, Hirschel McGriff, Chuck Bound [00:09:00] and Jimmy Anslow raced in scattered events that season. None competing the full season. Herschel McGriff, an age-defying Lumberman from Portland, Oregon began racing in 1945.

In 1950, he teamed up with co-driver Ray Elliot to win the inaugural Mexican road race in a 1950 Oldsmobile. I believe that car was on display when he was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame a couple of years ago. Later that summer in 1950, McGriff Journeyed diagonally across the country to South Carolina to finish ninth at Darlington Raceway in the first Southern 500.

He then went on to win four cup races in 1954 before stepping away from the sport until the mid sixties to raise his family to develop his businesses. Looking back now, we can see that McGriff already approaching 50 in 1975. Was more or less still getting warmed up at an age where most drivers were considering retirement.

At this stage of his career, he set his sights on competing at Le Mons, and in 1976 McGriff and his son traveled to [00:10:00] France and competed in the 24 hours throughout the 1970s. He often raced at Portland Speedway, his home track, where he won five straight Winston West races in between 1971 and 1973.

Beginning in 1980, he committed to full-time Winston West Seasons and McGriff was voted Winston West’s most popular driver for 12 consecutive seasons. He won the series Championship in 1986 and claimed 34 West Series victories. His last one coming in 1989 at the age of 61. McGriff strapped himself into a West Series event in 2018 in Tucson, Arizona at the age of 90, and he was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame a couple of years ago.

McGriff is also the all time winningest racer at Riverside. As Shav Glick, a member of multiple halls of fame will covered motorsports for decades. For the Los Angeles Times reflected shortly after Riverside’s 1988 closure on a cool Saturday in January of 1969, the Perx 100 unveiled a driver who went on to win more road races than [00:11:00] anyone else would ever win There.

Herschel McGriff, almost totally unknown in Southern California. Started 41st in last, but by the sixth lap he was in second and he wound up passing Ron Grable to win. Who is this guy? The assembled media and the track officials asked, well, McGriff scored his 14th and last Riverside victory in the 1985 Pep Boys 300 at the age of 57.

He was 60 when he drove in the 1988 Budweiser 400. The final NASCAR Winston Cup race held at Riverside, where he also served as the events. Grand Marshal McGriff did not race full-time in the series from 1973 through 79. In 75, he competed in four Winston West Series events, but three were joint cup races, two at Riverside and won at Ontario.

He competed at Evergreen Raceway in Washington in his only pure Winston West contest where he finished second behind elder. So that following January 16th at the Winston West Awards banquet in early [00:12:00] 1976, Ray Elder received a $10,000 bonus for claiming the championship at the Winston West Series banquet held at Riverside.

Runner up. Sonny Easley received $6,500 for his efforts finishing second in 1975, his last full-time season on the circuit. He also finished second in 1973 easily, who began racing in 1963. Mounted a respectable career on the West Coast, including eight victories in the circuit before losing his life in a freak accident while practicing at Riverside In 1978, Douglas Grunts, one of his crew members, also perished in the accident.

Chuck Wal finished third overall and picked up $5,000 for his efforts. The Burbank driver only won his only career events that year. But it truly was a night to remember for the racing farmers race crew Chief and brother Richard Elder won the Golden Ranch Award and NASCAR representative Ken Piper honored Fred and Laura Elder with a special appreciation award for their efforts to promote racing on the West Coast for over a decade.

Fred served as car owner and family matriarch. Laura took care of the rest of the family and young grandchildren. It was a [00:13:00] sweet award ceremony, but the window was closing for El duress. The 76 season approached after failing to do so in 1975. Elder hoped he would finally score an opportunity to race full-time with the Winston Cub series at the start of the 1976 season with two children to support in the family farm to maintain a temporary relocation to where the big Winston Cup teams were based anywhere throughout the southeast.

It needed to happen soon, but an opportunity with the sports Premier Division did not materialize worse. Olympia Brewing opted to discontinue their sponsorship commitment, and the racing farmers were back on their own. The Washington based brewery shifted their marketing objectives and began focusing on their own series across Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Consequently, with no corporate cash. Elder decided not to compete for a seventh Winston West Championship in 1976 as he warned his fans the previous year unable to land sponsorship and committed to the family farm and family matters. Ray Elder pulled out of the sport for nearly all of 1976 and the racing farmers [00:14:00] seized operations.

Richard Petty would race for his seventh Cup Championship in 1976. Ray Elder would not race for his seventh West title. That 76 season opened as it often did at Riverside with a combined cup in West Race. And as always, a group of regional regulars took a stab at making the race every January and June.

During the 1970s Winston Cup drivers had to muscle their cars up and down and around an unfamiliar road course. Their crews tasked with setting up a car to turn right. Back then, it was the only road course on the schedule. Watkins Glen would not become a series staple until 1986. The Winston Cup Stars had to compete against a group of talented drivers and crews with a home track advantage.

And not surprisingly, the south versus west dynamic was fodder for the California sports writers who ramped up the pre-race hype in the days leading up to the. Benny Parsons who finished third at the previous Riverside Race in June, 1975. Mentioned both Elder and Jimmy Insula as two of the guys to beat in a pre-race interview.

Parsons the 73 cup champion knew he had to finish ahead of the local [00:15:00] ringers if he hoped to produce a good result to start the 1976 Winston Cup season. Well driving for a wood brothers racing. David Pearson earned his first win at Riverside after 13 tries. That same Sunday, the Pittsburgh Steelers defeated the Dallas Cowboys in Super Bowl 10 by a score of 2117 Kele Yarborough finished second in front of nearly 55,000 race fans.

This race would also mark the last time two Winston West regulars would finish in the top five at Riverside, Jimmy, and slow. Starting way back in row 13, drove all the way to a lead lap, podium finish, taking third ins. Lo bested Elder who entered the Riverside race. Hoping to again spoil as he did in 71 and 72.

Elder came from row five and battled to a fourth place result. The first driver won lap down. Elder put himself in position for Cup Series win number three at one time, racing side by side with eventual winner Pearson at one point in the race. Eventually, elder ran out of room and slid off the track going on to muscle to a fourth place result.

A lap down [00:16:00] Betty Parsons, by the way, rounded out the top five Winston West regulars once again took it to nearly all of the cup regulars. But that was just about it because good runs for West and west drivers wanes considerably over the next 10 years. At both Riverside and at Ontario. The way the 1976 season was set up, a lengthy scheduling gap, gave West Coasters plenty of time to prepare for their true season opener and the spring approach.

Both racers and fans realized there would be a first time champion in 1976. Chuck bound only 22 years old, but already a Winston West veteran had the talent, resources, connections, and personality to make a mark on a national series someday. He was Herschel McGriffs son-in-law, grew up around and raced against his dad, dick bound in many events, competing in his first series race at the age of 16 in 1970.

After two strong Winston West full seasons in 72 and 73. Chuck Bound raced a limited number of events in 74 and [00:17:00] 75, however, he consistently ran up front with the leaders posting 35 career top finishes outta 75 races. Dick Bounds Rose Auto wrecking sponsored his son Chuck’s cars through the 1975 season.

However, in 1976 bound would compete in the series. Driving a 1975 Chevy Laguna, prepared by fellow North Westerner and engine specialist Jack D. McCoy. Not to be confused with the champion driver from Modesto. With Gerald Craker serving as car owner Leaks Drywall, a local company operating out of Oregon, his primary sponsor.

With additional sponsorship and assistance extending beyond the family business bound was positioned to become the first driver other than elder or McCoy to win the championship. Since Scotty Kain did. Winning back to back titles. In 1967 and 68, on June 27th, Chuck Bound began his championship run in the Winston West regular season opener at the paved five eighth mile oval at Evergreen Speedway.

It was bounds only series win that year. The 1976 season consisted of 13 [00:18:00] races. Three of which were combined Cup events, two at Riverside in January and in June, and one in Ontario in November. Just like the Winston Cup series commitment, consistency and competing laps were again, the keys to a championship run on the Western circuit as it had been so many times before.

Stan was the only driver to compete in every race, having the funding team support, and time to do so. The 22-year-old driver never finished outside the top five the entire season. He competed every lap, but one when he finished second in the series return to Evergreen that summer. His incredible consistency made for a runaway points battle, something NASCAR and most racing sanctioning bodies have struggled with since the first champions were awarded over a century ago.

Some of course, implementing a playoff system or double points paying races in an attempt to remedy this longstanding issue. But what a difference a few years makes the drivers who won so many of the races in the first half of the 1970s were now gone. They were outta the sport or they weren’t racing in the West Series full time.

Enter [00:19:00] 41-year-old brand new champion in 1977, bill Schmidt. He established himself as a consistent tough series competitor in his 74 debut season, and picked up his first series Victory the following year, coming in the Coca-Cola one 50 at Portland Raceway. In 1976, he returned to Victory Lane, taking the Checkers at the one third mile oval at Anderson Speedway in Shasta, California, which he also owned and operated.

In 1977, schmick picked up. Three wins and 13 top fives in his number 73 Chevy, which featured old Milwaukee sponsorship in some of the races that year. Schmid competed in all the races for the first time. Only two drivers of Schmid and bound competed in all 20 scheduled races including the two joint cup events.

Schmid won the championship with a 111 point March. One of the best drivers to emerge from Northern California. Schmidt remained competitive into his fifties and wound up with four series championships. His 19th and final Winston West series win came in 1992. At the age of 56, perhaps only Herschel McGriff [00:20:00] raced against more future NASCAR Cup series regulars on the West Coast.

As often as Schmidt both often bailed it out on West Coast Bull rings with young drivers who would find their way to full-time rides in the Cup Series many years later, Chad Little. Derek Cope and four time truck series champion Ron Hode Day, Jr. Were some of the drivers that they battled against as though they were starting their careers.

Interesting combination of generations racing during that time because Schmidt also raced against Ernie Irvin, who raced in his first full-time cup season in 1988 and helped put West Coast stock car racers on the national stage for good regionalism. Persisted in American stock car racing, headed into the 1980s.

Southeastern drivers still dominated, but Irvin was one of the drivers who began to change that permanently. The second generation versatile driver from Salinas, California won the 1991 Daytona 500 and wrapped up his injury. Shortened career with 15 wins in NASCAR’s top division on all types of tracks.

Also somewhat overlooked by racing communities east of the [00:21:00] Pacific Coast, both racers and historians. Ernie’s Father Vic, for over two decades was one of the top local pilots on the West coast. Vic Irvin picked up his lone career. Winston West win at one of its most iconic and toughest tracks. Taking the Checkers at Ascot on May 30.

Ron Hornaday is another driver I should have mentioned who also saw success racing the series in the 1960s. Moving into 19 78, 2 big early storylines unfolded before they even took to the racetrack. Chuck Bound was gone and Ray Elder was back down, relocated to Charlotte with aspirations to land a full-time Winston Cup ride.

But opportunities did not come to fruition as he continued his racing career east of the Mississippi in 1979. He finished seventh in the Daytona 500 and later that July was credited with a sixth place in the firecracker 400 at the same track down race in roughly 50 cup events in the seventies and eighties.

And his persistence and talent would pay off. He would race four Seasons in the NASCAR North Series and two [00:22:00] more stints with the NASCAR Bush North Series in 87 and 88, and battle it out with Northeastern Regional ACEs, such as Dave Dion and Robbie Crouch. There was a lot of tough competition during this time as some New Englanders competing in the division versed on moving on to competing in the Winston Cup series.

But though it was a long journey for bound, it was certainly one mission accomplished for the West Coast, more specifically, the Northwest, when he captured the 1990 NASCAR Bush Series Championship with six wins that year to boot Elder, however, was set to run a full season in 78, the first and only of his career without the racing farmers.

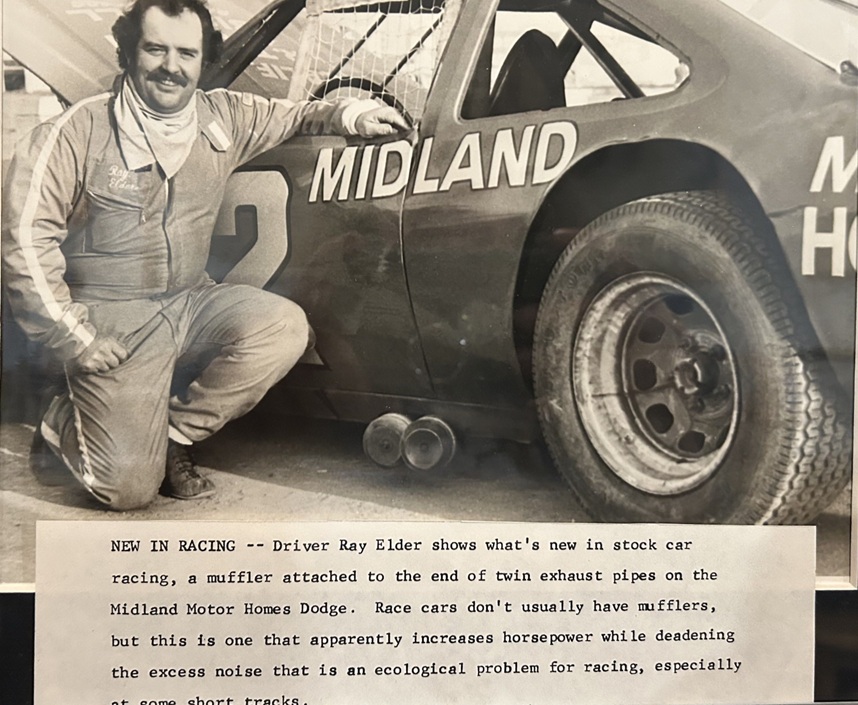

He was also driving a red and yellow number 32. Not the iconic 96 and Familiar Blue. The team was a serious championship contender with strong ownership with Dave Hill in sponsorship for Midland Homes and some former racing farmer team members providing support at Las Vegas. Later that summer. Elder won his final West Series race and won two races that year, and despite many good runs, he wrapped up the season in fourth [00:23:00] place Overall.

Not only did he add to his impressive resume, he also showed that he could win without the full racing farmer’s operation. Overall, Sik Championships 47 series wins countless heat victories and two cup wins. He was so good on all different types of tracks, but probably more than anywhere else mastered the dirt surface at Ascot Park.

The best racers adapt to nuances and compositions of different dirt surfaces. They understand racing environments and the best crews also recognize how environmental factors dictate the speed and performance of a racing machine. Ascot was unique as Glick reflected in 1990. The year of its closure.

Several things set. ASCO a park from other tracks. For one, it is 60 yards short of a half mile. So it’s exceptionally fast and being close to the ocean. The sea air rolls in during the evening and helps keep the track from drying out and becoming too slippery at Ascot. Elder perhaps best understood these factors more than any driver of his generation.

No NASCAR Hall of Fame yet for Ray Elder, it’s hard to imagine the well-informed selection [00:24:00] committee ignoring his accomplishments much longer. In 1978, elder was the only driver other than Jimmy SLO to win more than once that year. SLO had the best Winston West Series season of his career that year, originally for Mission Hills.

California INS Slow began racing at roughly the same time as Elder in the early 1960s. However, ins slow hit his stride a little bit later in his career. He made his Winston West debut in 1970, claiming his first victory the following year, coming at the Quarter miler at Craig Road Speedway on the outskirts of Las Vegas in 1972.

He finished third points, winning seven races along the way, including four in a row in a span of six days. Gentleman, Jim, as he was known for his clean driving style, was popular and respected among fans and competitors on the west coast. Insular drove the number of 38 for most of his career. It was nearly as iconic as elders 96 on the West Coast.

But his best, Winston West Seasons, however, came driving the number one car for Jerry Craker, who was one of the top owners of the decade. [00:25:00] He was the same car owner that Chuck Bound had great success with before he relocated to the East Coast in 78 in slow one nine of 22 races. The 1973 West Season finale took place on Thanksgiving weekend and INow again proved he could hang with and beat some of the best funded and seasoned Winston Cup drivers After finishing behind the King who traveled out to Arizona to race.

In the event, hoping to spoil the show, which he did, he claimed the pole position and won the Arizona Napa two 50 ins. Lo was second, and then there were a couple more cup drivers who came out west with their season having been completed. Bobby Allison finished second Yil bonnet took third. The race was held the week following the conclusion of the 78 cup season and proved to be a much needed confidence boost.

To wrap up Richard Petty’s season, petty Enterprises struggled to get the Dodge Magnum up to speed during most of the year, and the king went windless in 1978 for the first time ever, and also finished sixth and points. It was the worst he had finished in his standings, not including his abbreviated season in 1965.

[00:26:00] Since placing eighth in the points in 1962. It’s a little foreshadowing here as we move into the final year of my, of my study, of my presentation, 1979, we can get into all, everything that took place in February at the Daytona 500, the Great American race. We can never assume that everybody in the audience knows some of the commonly known racing facts that we talk about, but I think goes out.

Say that most of us know that the 79 Daytona 500, the fight between Donnie, Bobby, and Kale. Was a pretty big deal, and it snowed that weekend and people were stuck inside and they had nothing else to watch on television. Football season had ended, and you cannot argue against how much of a benchmark event that was for stock car racing, particularly for nascar, but it was also one of the most important seasons for NASCAR as well.

But NASCAR’s aside for a moment, 1979 was tough for many Americans marked by a struggling economy and yet another gas crisis. 79 was also a benchmark year for racing, and many people in this room over the years discussed some of the [00:27:00] developments from 1979 in previous presentations. The cart USAC split being perhaps the most memorable and significant, and that it permanently altered the trajectory of American Open Wheel Championship racing.

But there were a lot of different things that took place in 79 that really directed racing’s direction headed into a new decade. What about the Winston West Series? A few up and comers began making noise in the series. The season featured more drivers than usual, competing in the entire schedule, and an exciting points battle unfolded.

The most promising newcomer was Tim Williamson from Seaside, California, which is not too far from Monterey. Williamson began competing in go-karts as a high schooler before making the jump to race cars in 1974. He spent a few seasons developing his skills at Merced and Watsonville, and in 1978 he won his first Winston West race in his very first attempt leading 99 of a hundred laps in a 1976 Chevy at Stockton, 99 Speedway.

In the fifth event on the series calendar, he competed in five races in 1978 and also took pole position at the [00:28:00] Sears Point Road course winding up six. He was only 22 at the time. Williams, I got off to a hot start at the outset of the 1979 racing season in January. He won the 300 kilometer NASCAR Grand American Race at Riverside ahead of Bobby Allison and Herschel McGriff.

He finished ninth at the season opening NASCAR Cup series event at Riverside in his old mobile. And then he won again in June when the Grand American Division returned to Riverside, the end of the decade Also saw the emergence of one of the greatest Canadian stock car racers of all time racing. Roy, the Stock Car Boy Smith won his first career race in 1979.

He began competing in the series in the seventies and began a full-time racer in the eighties. Claiming back to back to back championships from 19 83 82, the first driver to three-peat since Elder did it, Smith won another in 1988. He finished 10th in the Stans in 1979. Having competed in just over half of the series schedule that year, Sharon Bishop became the first woman to run full-time in the series.

The Washington based driver was somewhat of the Janet Guthrie of the West Series. Who raced from [00:29:00] 1975 through 1980 in NASCAR competition, paving the way for regional racers such as Bishop with her husband, serving as crew. Chief Bishop raced in three seasons, never competing a full schedule, but regularly mixing it up with the best drivers in the series and putting together some good runs along the way and.

In 1979, Bishop wound up ninth overall in the Winston West standings. The 79 season was tight all the way to the finish, much closer than the previous season. Five drivers competed in all 16 events and that same content finished in the top five, but only separated by 105 points. Williamson maintained the points lead throughout most of the fall and a season worth of racing came down to the final event.

Schmidt and Williamson led the championship battle into the season finale in the Napa, Arizona two 50. At Phoenix, though Jimmy Anslow and Richard White were also still mathematically in the mix. Schmid finished 11th, five laps down while Williamson took fourth one lap down. Schmidt earned that finish after crashing in an oil spill on the track left behind.

[00:30:00] After Jimmy Insula blew his engine on the second lap. Schmid crashed hard into the wall and returned to the race. He nursed his car around the one mile flat oval, and every lap he completed and every car he passed was critical. At the end of the 156 lap race, only five points separated. Schmidt, the championship veteran, and Williamson, the emerging superstar.

Williamson had an average finish of 7.8. Schmitz was 9.1. Williamson had one victory. Schmid had four. Schmidt had nine top fives. Williamson had eight. But Schmidt had 10 top tens to Williamson’s 13 when Waltrip was getting better and better and making a lot of noise. It was just a matter of time before he was gonna win a Cup championship and there was a real good chance it was gonna come in 79.

’cause at the time it was the closest championship chase in history. It was a season long neck to neck battle between Petty and Darryl Waltrip. And the championship would be decided at the final race. At the Indianapolis of the West, the 2.5 mile oval at Ontario. Petty finished fifth on the lead lap while DW came home.

Eighth one lap down. [00:31:00] Both received five crucial bonus points for leading a lap. I missed that old NASCAR point system. It was finishing with one through 10. I think you received five points and it was down to four points, then down to three points. I think that ended right about when Winston. Got outta the sport and Nextel came in and, and the playoff system was put in, but I still miss that.

It rewarded consistency. That old system by the numbers. Petty won five races. Waltrip claimed seven victories. The King’s average finish was 6.4. Waltrip was 7.0. Petty had 23 top fives. DW had 19, petty had 27 top tens. Waltrip had 22. Petty won a single poll. Waltrip was credited with five. But it’s the littlest of little things that really were part of the title of my presentation comes from.

Yes, in many instances, luck factors into a season just as hard work, hard driving, brilliant strategy and precise pit work factors into championships just as often down to individual races. Then there are those moments that are little known at the time to have massive implications down the road. A lot of you, or some of you have probably heard this story before.

It shows [00:32:00] how sometimes statistics and numbers are only part of the equation, whereas impact is sometimes unquantifiable reenter Jimmy and slo. By the time the NASCAR Cup series returned to Riverside for its second date in June, 1979, INS had clearly made his mark with the Cup Series drivers. He had already posted eight top tens, four of which were top fives in cup events from 73 through 78.

Seeing success at Riverside in Ontario too. So he was good on the road course and he was able to run to run fast at Ontario. He was also on his way to another excellent Winston West season. Although he didn’t repeat his champion, he was locked up in the points battle all season long, ultimately placing third in the championship.

He won two races, won in Sears Point. Another one became Washington and Ins slow, started the June Riverside. Then on the front row after qualifying second. He set the track record in 1978 in the 1977 Camaro for a Grand American stock car race with a lap of one 17.585. So it was no surprise he would qualify outside the front row.

By the way, next to rookie Dale [00:33:00] Earnhardt for the 1979 Summer Cup race at Riverside. In fact, the 79 cup season featured the emergence of Earnhardt. He won his first race that year and took rookie of the year honors. In the final race of 1978, insular started the Ontario race for Earnhardt. This allowed the young contender to hold onto his rookie status for the 1979 season.

As per NASCAR rules, insular earned the seven place finish. Earnhardt came home with insular, was running in the top five at Riverside until blowing his engine on lap 45. His day came to an early end. He cooled off and changed into his street clothes. The race took place on a hotter than normal day, and the drivers still competing in the race.

Had to contest a difficult racetrack under exceptionally uncomfortable weather conditions. Meanwhile, Richard Petty, who is as tough as they come, was struggling behind the wheel of his famous 43 to make matters worse for Petty. He was already not feeling well on race day, and he was wrestling with mechanical issues with his Dodge crew, chief Dale Inman and Engine Builder.

Maurice Petty knew Richard would need to [00:34:00] vacate the car at some point. And there’s a great account of this story and I, I just wanted to give a shout out by former Reer Rick Crow, who did a podcast with Jimmy Slo. I mean, you can find it on YouTube. It’s a 90 minute discussion with INS slow. It’s entertaining and it’s insightful, and Jimmy really does a great job talking about some of the other side stories involved with that race at Riverside.

Maury filled in for the king. He was asked to drive in relief for Petty with 20 laps left in the event. The 43 rejoined the race in fourth place with insular. Now behind the wheel, he passed kale and finished third NASCAR as it always had awards. The points in finishing position to the driver that takes the opening green flag and that car’s number.

There have been some notable relief drivers taking the checkered first and not officially credited with a victory. NASCAR is not alone. Ray Harun had a relief driver in the first Indy 500, but few remember his relief driver, Cyrus Paki. As Mike Hembry, longtime Motorsport journalist pointed out a few years ago, a rear view mirror of that [00:35:00] 1979 season, which showed numerous places in which the tide ebbed and flowed, but insulars, smooth and steady finish kept petty in the top five with a few minor slipups.

The king may not have had seven championships, and Dale Edmond may not have claimed eight career championships as a crew chief. He had seven with Patty and one came later as crew chief for Terry Leni in 1984. And that’s where my disrupting history reference kind of comes in the most for this presentation.

Sometimes it’s the smallest mid-season matter of a few laps that can have a great effect on a championship and on legacies. Nearly all Winston West drivers remained regional racing stars. And heading into the 1980s, Westerners continued making their biggest impact on the Cup Series as owners, innovators, crew chiefs, administrators, and mechanics.

But just like in baseball’s early days, there were stars who never made it east. It wasn’t that long ago when the furthest west that Major League baseball extended was Chicago and St. Louis. In the 1970s, national corporations were mostly [00:36:00] disinterested in signing Western talent to their sports marketing platforms.

The few mid to large-sized businesses in the Winston West Series were regionally focused companies with a limited national outreach. But it’s still hard to not wonder what if from time to time in 1980 the West Coast lost its rising young star. Tim Williamson died in the crash while qualifying for a Grand American Series event at Riverside.

A day before his 24th birthday. Williamson had the talent funding crew and support, but we’ll never know. Ken Clap, founder of the West Coast Stock Car Racing Hall of Fame and a longtime NASCAR West Coast executive for decades. Mentions in his autobiography that Williamson likely had a cup ride for the 1980 Daytona 500 with car owner JD Stacey, and K Clap put it very, very simply.

He believed, quote. Williamson could go all the way. Still as the Winston West Series enjoyed sustained commitment from nascar. It remained a regional, minor league series with a driver talent pool capable of making the jump. If the major leagues came calling. Finding a job is a job. [00:37:00] Therefore, the only route to a cup ride at this time in the sports history meant a driver was willing to move East.

And commit to a full-time search, lacking the necessary resources and commitment needed for this level of outreach. West Coast drivers and their efforts to garner sponsorship and interest from established cup teams remained mostly fruitless throughout the 1970s. Ray Elder with a family and farm to take care of, not take that chance.

Chuck Bound, who was much younger, did relocate East, and although he enjoyed local and regional success in the 1990 Bush Series Championship, the full-time ride remained elusive until the age of 40. In 1994, he linked up with car owner Bobby Allison. And Jimmy Fenning as his crew chief. Unfortunately, that season and his career was cut short by a horrible crash.

Regionalism persisted in American stock racing, and getting into the 1980s, Southeastern drivers still dominated. Eventually West Coast drivers found national success as many of the tracks they competed on, disappeared, replaced by strip malls, neighborhoods. And rarely with open park space in the second half of the 1970s, auto racing forever became a much [00:38:00] larger component of debates over place and space.

Although the Federal Noise Abatement Act of 1972 granted auto racing exemption from noise statutes and motorsports survived the 73 and 74 OPEC oil embargo. Nearly every week from 1975 through 1979, national Speed Sport News and illustrated Speedway News included at least one article updating the status of a battle between a racetrack operator and his or her neighbors forced to address civilian noise complaints.

Promoters attended workshops to gather tips regarding noise abatement and to develop public friendly policies. Basically, the survival of a racetrack depended on an owner’s willingness to cooperate with citizens and government officials, not drivers and fans. Regardless of a track operator’s vain attempt to silence cars and work with surrounding community sprawl and a growing demand for quiet, it still killed countless speedways.

However, states and communities enacted their own ordinances. Which led to curfews and muffler equipped race cars, and that’s why I’m closing with this photo of elder in 1978. I love the, he’s got [00:39:00] the, the stash going, which is outstanding opposing next to his new ride, the Midland ride from 78. The caption isn’t about going for his six championship and having 43 career wins at the time and, and all of his success on the track.

It’s about the muffler and that just kind of shows that, you know, racing was, I mean, part of a bigger. Environmental conversation after the OPEC Oil embargo. Nearly all of the racetracks were Jack McCoy won two Winston West Championships and Chuck Baum, Jimmy Anslow and Herschel McGriff won. Their series Championships are long gone.

It was clearly a back in the good old days era for motor sports on the West coast. But now looking back 50 years since Ray Elder’s sixth to the final championship in 1975, we can see that changes were underway, particularly in the business of racing, the politics of racing and criticism of autosport.

With an increasing awareness of the place of motorsport within the environment. The racing green initiatives we see today are rooted in the American environmental movement during the 1970s. Thanks everyone.[00:40:00]

Thanks, Dan.

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This [00:41:00] episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation.

Through the modern age and into the future. For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org. We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. [00:42:00] We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, mini SOS and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 NASCAR Winston West Series: A Turbulent Era

- 01:55 The 1975 Racing Season: Challenges and Changes

- 03:31 NASCAR Pacific Coast Late Model Division: Early Days

- 04:18 Riverside International Raceway: A Hub of Motorsports

- 04:50 The Evolution of NASCAR Winston West Series

- 05:26 Key Drivers and Their Legacies

- 06:19 Ray Elder: A Racing Legend

- 09:05 Herschel McGriff: The Age-Defying Lumberman

- 13:03 The 1976 Season: New Challenges and Opportunities

- 16:32 The Rise of New Champions

- 26:02 The 1979 Season: A Benchmark Year

- 35:32 The Legacy of the Winston West Series

- 39:57 Conclusion and Acknowledgements

Livestream

Learn More

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

The 1975 season opened with notable absences. Jack McCoy, a two-time champion with 54 victories, stepped away. Dick Bown, a fan favorite from the Pacific Northwest, also retired. Their departures left Ray Elder – the pride of Caruthers, California – as the veteran standard-bearer. Elder seized his sixth championship that year, cementing his legacy with victories on dirt at Ascot Park and consistency across 18 races.

Meanwhile, Hershel McGriff, the lumberman who began racing in 1945, defied age and expectations. Though he raced part-time, his performances at Riverside and Evergreen reminded fans that passion could outlast decades. McGriff’s career stretched astonishingly into the 1980s and beyond, culminating in a Winston West title in 1986 and a Hall of Fame induction.

By 1976, the series saw generational change. Chuck Bown, just 22, captured his first championship with remarkable consistency, never finishing outside the top five. His journey eastward eventually led to a Busch Series title in 1990, proving that West Coast talent could succeed nationally.

Bill Schmitt followed, claiming his first championship in 1977 at age 41. Known for his grit and longevity, Schmitt would go on to win four titles, racing well into his fifties. His battles against future Cup stars like Chad Little, Derek Cope, and Ernie Irvan showcased the series as a proving ground for national contenders.

No venue embodied the Winston West spirit more than Riverside International Raceway. Hosting Cup and West events alike, Riverside became the crucible where local heroes challenged national champions. Elder’s victories over Cup regulars in 1971 and 1972, and McGriff’s dominance on its road course, underscored the West’s competitive fire. Even as Riverside closed in 1988, its legacy as a battleground for regional pride endured.

By 1978 and 1979, the series welcomed new names like Jimmy Insolo and Tim Williamson. Insolo, nicknamed “Gentleman Jim,” delivered his best season in 1978, while Williamson’s breakout in 1979 hinted at a new generation ready to carry the torch. These years coincided with broader upheavals in motorsport – the CART/USAC split, another gas crisis, and the nationally televised 1979 Daytona 500 that catapulted NASCAR into mainstream culture.

The Winston West Series of the late 1970s was more than a regional competition; it was a testament to motorsport’s ability to adapt. Amid economic strain and cultural shifts, drivers, crews, and fans kept the spirit alive. Their stories – of farmers turned champions, lumbermen defying age, and journeymen seizing opportunity – reflect the resilience of racing itself.

Today, as historians and enthusiasts revisit this era, the Winston West Series stands as proof that even in the shadow of crisis, motorsport found ways to endure, evolve, and inspire.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)