In the annals of motorsport history, few machines evoke the engineering prowess and post-war resurgence of Mercedes-Benz like the W196. But what if the trajectory of Formula One had bent differently? What if a coalition of Italian and Austrian engineers had mounted a credible challenge to Stuttgart’s Silver Arrows in the early 1950s – ushering in the mid-engine revolution years ahead of its time?

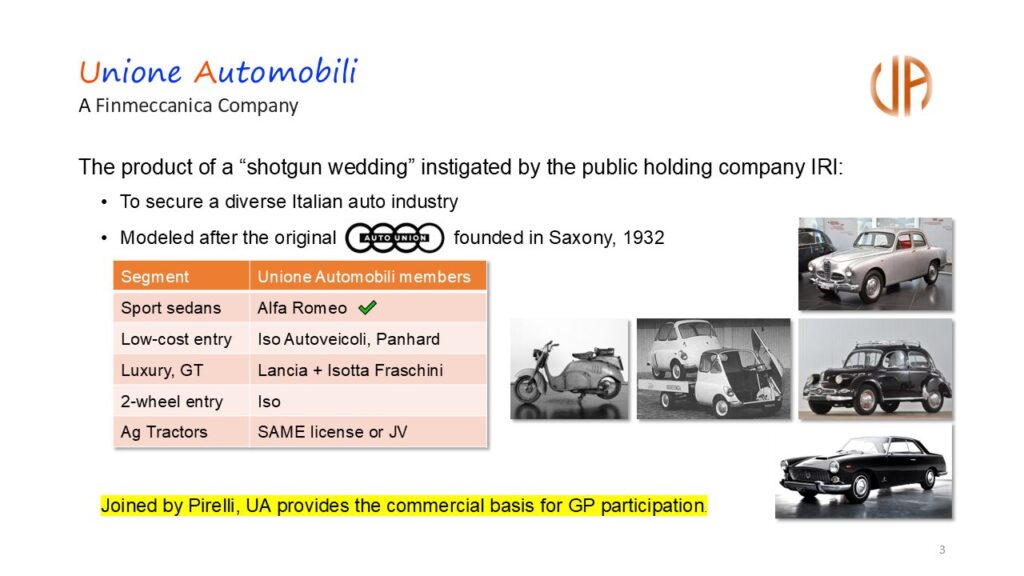

Continuing where he left off last year, Dr. Karl Heinz-Mertins, a mechanical engineer and mechatronics expert with decades of cross-disciplinary experience, invites us into an alternate history. His speculative analysis, grounded in real-world technical feasibility, imagines a scenario where a fictional Italian conglomerate – Unione Automobili (UA) – emerges as a counterforce to Mercedes-Benz, leveraging mid-engine design, aeronautical principles, and a bold engineering philosophy.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

The Historical Context: Mercedes Reawakens

By 1951, Mercedes-Benz had reemerged from the ashes of WWII, unveiling the luxurious 300 series and signaling a return to racing. Their early foray into motorsport with pre-war Silver Arrows in Argentina proved underwhelming, as two-liter Ferraris outpaced their aging three-liter machines. This embarrassment catalyzed a more methodical approach: the development of the 300SL sports car and, eventually, the W196 Formula One car.

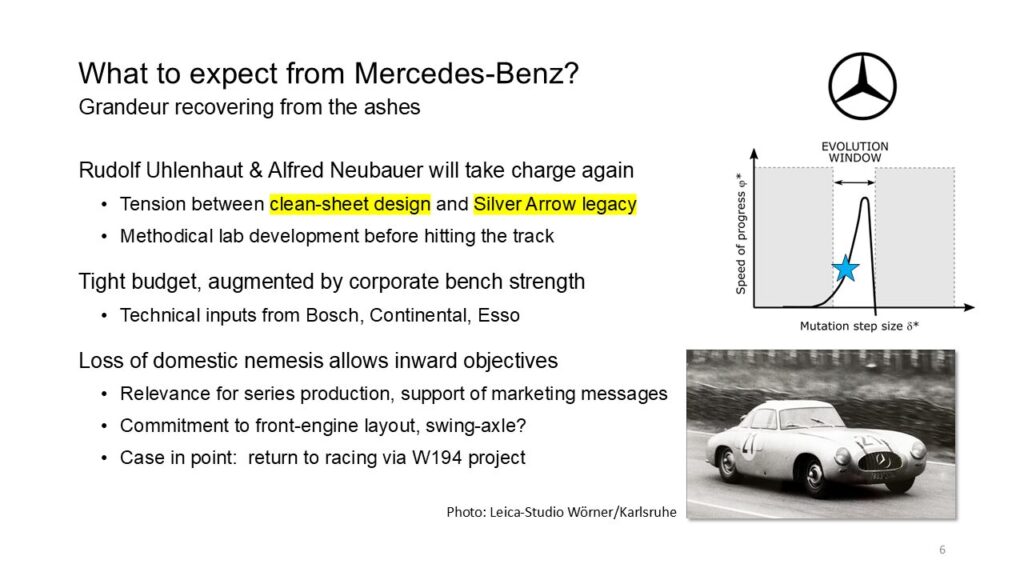

Mercedes’ engineering culture – defined by rigorous subsystem testing, conservative innovation, and component-level optimization – set a high bar. Their evolution strategy favored incremental gains over radical departures, a philosophy that would shape the W196’s front-engine layout and fuel-injected powertrain.

Spotlight

Dr. Karl-Heinz Mertins (“K-H”) holds degrees in mechanical engineering and a doctorate in mechatronics/ag engineering from the Technical University Berlin, Germany. In more than 35 years of engineering and business experience in Europe and the US, he focused on product innovation and new business incubation, applying cross-disciplinary methods with cross-cultural considerations. His work included experimental work on intelligent mobile equipment and wind energy systems in multinational corporations and start-ups. His enthusiasm for F1 goes back to the 1961 season.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, delves into an alternative history of motorsports, exploring how an imaginary Italian automobile group could have rivaled Mercedes-Benz’s W196 in the 1954 Grand Prix season. Led by engineers like Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, the team focuses on a mid-engine layout, leveraging aerodynamics and innovative engineering techniques. The narrative includes a probabilistic SWOT analysis and historical insights on post-WWII automotive development, emphasizing the importance of strategic differentiation to outperform Mercedes. Dr. Karl-Heinz Mertins, with his extensive engineering background, presents both real and hypothetical scenarios, highlighting key technological advancements and the speculative potential of an Italian conglomerate challenging the dominant Silver Arrows.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports Series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer family.

Crew Chief Eric: How to beat the Mercedes-Benz W 1 96. An alternative history accelerates the Mid-engine Revolution by Carl Heinz Mertons. The new two and a half liter formula of 1954 raised the bar for engineering excellence and cost of entry to the pinnacle of motor racing. With Mercedes-Benz, leaving the shadows of World War II and becoming an accepted participant in motor racing, again, the Grand Prix community had to anticipate a full out effort of a new generation of Silver arrows.

Indeed, new standards were set with a series of W one ninety six variants born out of vast corporate resources supported by components suppliers like Continental Bosch, and so. In this story, the imaginary Italian UNE automobile previously formed of National Legacy Manufacturers [00:01:00] other than Fiat takes on the role of Auto Union Ag of the 1930s as an antagonist of Mercedes-Benz and Promoter of the Midian layout, a probabilistic SWAT analysis reveals what it would take to beat the mighty opponent for s Stuttgart.

This is the start for a motley crew of Australian and Italian engineers led by Robert Ein Hors to create a victorious challenger. The prescribed engine configuration is a compact V six and homage to the launch of brand breaking with Italian traditions. Emphasis is put on chassis development where innovations and tires breaks, and aerodynamics will provide decisive competitive advantages.

Dr. Carl Hinz. Mertons holds degrees in mechanical engineering and a doctorate in mechatronics and engineering from the technical University of Berlin, Germany. In more than 35 years of engineering and business experience in Europe and the us, Carl has focused on product innovation and new business incubation, applying cross-disciplinary methods with cross-cultural considerations.

His work included experimental work on intelligent mobile equipment and wind energy systems in [00:02:00] multinational corporations and startups. His enthusiasm for F1 goes back to the 1961 season.

Karl-Heinz Mertins: Like many people in racing, I’m bending the rules a little bit here, speaking to a society of historians. I will talk a little bit about the real history, but then we are often to an alternative history and give a picture of what could have been instead of what was.

So, uh, the question is how to beat Mercedes-Benz at the time when it wasn’t quite clear. That they would enter the um, 2.5 liter formula one race season in 1954. And so the model designation of W 1 96 wasn’t known yet. So it’s kind of blanked out here in the title. Let me give you a timeline of where this all starts, and then I will talk a little bit about what happened here on the left side before we get to [00:03:00] 51 in 51.

And all this is somewhat relevant to the story that I will tell in, uh, 51 Mercedes got back out of the destruction phase into the reconstruction and started building cars again. But not just any car. They started unveiling the, uh, 300 W 180 6 as an internal code, and it was a challenge to Rolls Royce to Packard, if you want.

So they wanted to really reestablish the company as a provider of luxurious cars and, and set the standard. Shortly thereafter in this presentation happened at the, uh, Frankfurt Automobile Show in April. Shortly thereafter, the board approved that the company should go back to racing and there was a green light given for.

A sports car project. First, the 300 SL to ease into [00:04:00] motor sports again after World War ii. Now, what happened before, other was of course, the World War II and before it ended, there were plans, particularly in the us the Morgenthal plan that foresaw that, uh, Germany should really be brought back to the Middle Ages and should have no.

Industrial capabilities anymore. The facilities that had survived the World War should be dismantled or destroyed, and, uh, it should be an agrarian society that, that would go forward and not be a threat to mankind going forward. Well, that plan, fortunately, didn’t come to pass. Instead, there was of course, an activity, some of that on the table, and some of it was under the table.

There were of course some of the, uh, Mercedes engineers that formed informal networks, and they were thinking about plans of what could they do and how could they survive, and at some [00:05:00] point go back to the former glories again. That happened and that led to things like the Unimark, of course, a utility vehicle, kind of an agricultural tractor, and of course that kind of responded to the Morgan for plan.

Of focusing on agriculture and not on things like racing or luxury cars. That machine, uh, was very successful. It was developed. It was very little means and, uh, with external help and the binger brothers chipped in and there were other. People that had allocations of sheet metal out for milk cans and and so forth.

And they all contributed because at the time, in 45 when the war was lost, Germany was under military rule and the area around Stuttgart was about the American. Administration then, and so material were scars and had to be applied for and to be a good reason as to why you wanted some material and you couldn’t ask for material for race cars, for example.[00:06:00]

Wouldn’t have been a good proposition. Moves on from there. Pretty quickly, the Arkansas plan gets replaced by the Marshall Plan. Money flows into Europe and the reconstruction is pretty fast and furious. So there were some activities already at the beginning of 51. A couple of the, uh, pre-war one 60 fours.

We’re brought to, uh, Argentina to run in one Cyrus at a couple of races. And the idea was, well, we were so successful with those pre-war silver arrows, we could probably just dust them off and use them again in, uh, this new age. It turned out they were not that successful, was the, uh, moving force behind all this.

He had a, a delegation going to Argentina with these cars engineer responsible for those who, how was not in the delegation. So things were probably not perfectly set up, [00:07:00] but those cars, three liter mercedeses were beaten by two liter Ferraris. And it was kind of a shameful event from a Mercedes perspective because the DNA of the company was indeed.

You make the best cars you can make and when you go racing, you go for the win. You’re not settling for second places. They had to rethink the solar operation and scale back a little bit. Go back to building a sports car and focus only once the dust settled and it became clear how Formula One would be organized in the future, that there would be indeed a new one.

A formula that would give preference to naturally aspirated engines, and it would start in 1954. It became clear. Now, that was the new goal for Mercedes, but in the interim, they were working on a race car that they could build out of this luxury car. Kind of a clumsy way to do it, but nevertheless, it turned out to be [00:08:00] quite successful around the same time, at the end of 1951.

Alfa Romeo, who had had two very successful years with the LF Fetas, decided that that wouldn’t be a long term proposition going forward with those cars. They were at the end of their development potential, and you couldn’t increase the uh uh, compression ratios and the supercharger pressures and so on, and you couldn’t deal with the fuel consumption that increased exponentially.

So the abandoned racing. Completely. Now if, if you are a competitor in this Grand Prix racing scene and you think about, well, I have to compete with Mercedes again, they’re not doing things half baked. You have to have the financial strengths. And you have to have the intellectual strength to build a true competitor, a good car that can indeed meet and beat Mercedes-Benz.

It takes something. So here [00:09:00] is where I, we are off into La la land if you want. So during 1952, where could a group come about that would make a challenge for Mercedes, not in France? I think, you know, the CTA arsenal was. Rolling disaster and would not have yielded a real competitor in England. BRM was a, uh, bureaucratic mess, and it wasn’t really going anywhere fast, and it was also too much looking backwards to the 1930s technology wise.

So I could see that scenario in Italy. If you reconstruct something like the ion that had been very successful in Germany and had provided this competitive product to Mercedes in form of the, uh, mid-engine silver arrows that were initially designed by failure net Porsche and. Engineering office and then, uh, Nan Ho in particular [00:10:00] insourced more and more of that activity.

So I suggest something like this, and. Bil should, uh, happen in northern Italy and it would be where, you know, out in Germany was pretty much mandated by the banks that they had to support the capital in Italy, the IRI, the state holding. To which Alpha Romeo already belonged, would be a good vehicle to provide some serious competition to fiat, which totally dominated the uh, Italian auto scene volume wise and value wise, something needed to be done because frankly, I think people with some foresight knew that companies like ER and Alpha Mayo.

By themselves couldn’t survive long term. Hindsight tells us that they didn’t, but we’re back in 1951 ish, two ish. This could have happened. We could have had a conglomerate of different, uh, brands that would cover different segments [00:11:00] in the marketplace. They could even have an, um, a foreign branch in France.

ARD would be a, a good candidate. In those days, you couldn’t trade easily across country boundaries. So Fiat had sim. In France, we would have ARD and uh, we would have a luxury segment where Luncher would play a big role. Ista Fch would also be integrated, the name rights would be acquired, and you would establish the luxury and the top end of the range.

With that brand, there would be an entry also, in terms of a tubial. Vehicles and the scooter, a pretty rugged scooter from is O was available. So we have already the low cost entry brand is O auto vehicle that makes this ISTA and they also made the scooter. So we cover that. And also in addition, goes back to last year’s presentation.

We also have a branch that [00:12:00] deals with ag tractors ’cause that helps. Uh, developed the metso join region in Italy, and that’s, uh, one of the motivators why. IRI will support the sole effort. This sole effort needs also to be joined by Pelli, which has an interest in promoting their tires. And altogether, this could be a competitor or could be the financial resource, intellectual resource to provide a real competitor to Mercedes.

So we have a few individuals here that will constitute the core team. But the head would be Robert Horst, who had ample experience in mid-engine cars at Ion before the war. After the war. He was involved in the Alia 360, which also was designed and outsourced and relocated team of Porsche engineering.

Fer. Porsche was incarcerated at the time in France, but his son and some of the old [00:13:00] team members were working there. I put here Kois as kind of the project manager in place as the right hand of Iran. Horst, who was certainly the intellectual mastermind, but not necessarily involved in all the nitty gritty.

So Nico is, will take care of that. He has, um, experience at the Alfreda program and we bring in. Different generations. I think from my own professional experience, I think it’s always very helpful when you have multiple generations on a team, not just an inbred group, so to speak, of gray beards. You need some of them, but you don’t want to have the.

Whole team of them. So we recruit and those are real people. Of course, as you know, Kalo Kitty and Choto Sini, both are already at Alpha Romeo. It makes sense to rely on them a lot for chassis and for development and test and so on. They’re enthused and they come very importantly [00:14:00] from the University of Pisa.

So they have at least in, in. Case and degree in aeronautical engineering, and we’ll see later on that taking license from or learning from aeronautical designs and skills and technologies makes a lot of sense when you want to build a world beat a race car. On the engine side, we lean more on the ER personnel.

There is of course Francesco Lio, who pretty much developed the V six engine at Luncher. The principles, at least the angle of 60 degrees. It goes back to him. He analyzed the dynamics of various V angles and when you look at the history of Blanche and you know, they experimented with everything from 11 degrees.

Downwards or upwards and 60 degrees is obviously the ideal, but there’s also a solution with 120 degrees later on. Dillo found [00:15:00] that already in the 1940s, so he is obviously a member of the team. Then, uh, the kina is maybe a more practical engine designer who can detail. An engine war, and he has shown that already as, as a long term launcher engineer, I couldn’t get any biographic information on him.

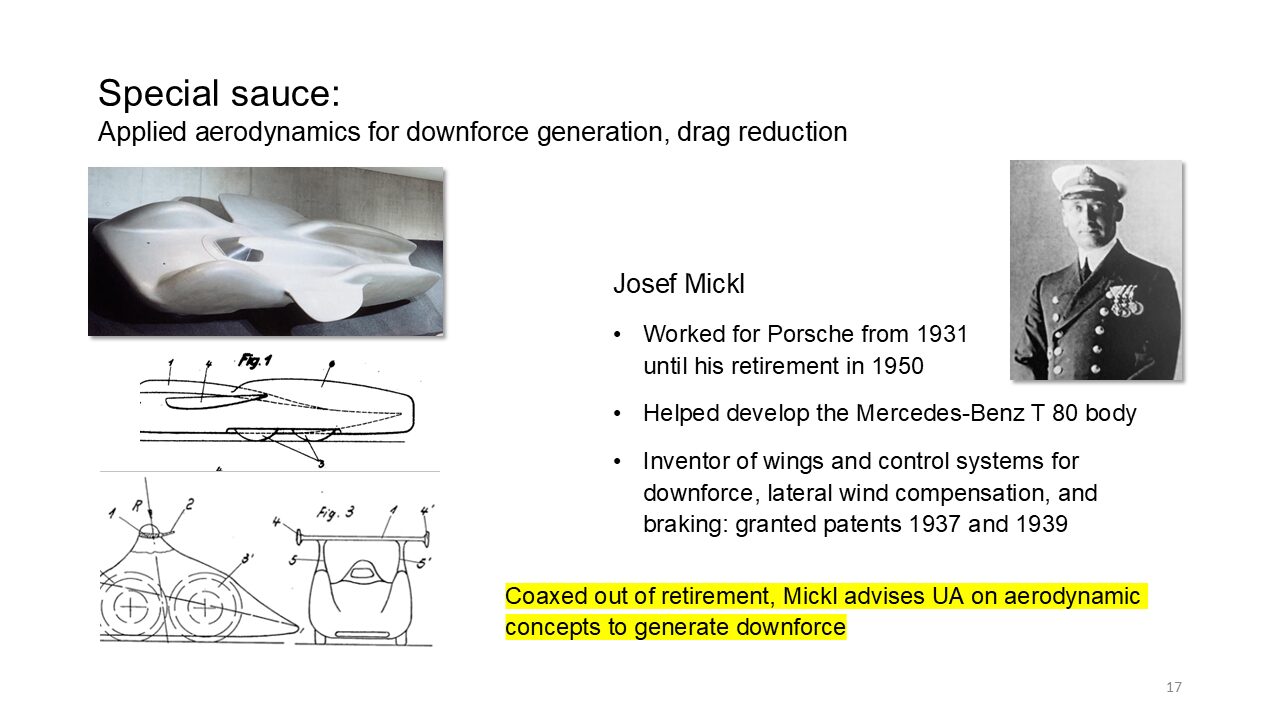

Maybe that’s where some librarians can help me in the future. And then of course, this fellow here. We’ll learn more about him. Jose Mika, who retired in 1950 from the Porsche engineering team. We’ll rehire him as a consultant because he’s a specialist in aerodynamics, and we understand aerodynamics will play a big role if we want to beat Mercedes.

And it’s also important to work very closely with the tire manufacturer. So we want to have somebody. I’m not particular about the name from Pelli, from the tire partner because suspension, layout and design [00:16:00] will have to be very closely coordinated with the tire capabilities. And so you want to have the tire people on your side.

It’s one of the lessons also from the Solar Arrow pre-World War II, where Mercedes worked very closely with Continental and that was very helpful to them. Porsche and uh, ot. We’re not quite as engaged with Continental, and it was to their detriment sometimes. So the first task of this newly formed team was before you start designing anything, you know, go by this ancient wisdom here.

If you know you’re enemy and you know yourself. You need not fear the result of a hundred battles. So find out as much as possible about Mercedes. Where are they going? What can you expect from them? Rather than focusing just on your own thoughts and say, we know best how to build the best race car.

Anticipate what your enemy or your competitor will do, and then not copy them. The goal is not to copy them. You cannot [00:17:00] out Mercedes. Mercedes, you know, if you try. It’s a losing battle. You have to do something. You have to look for unfair quote unquote advantages, and you have to do something different.

For example, mid-engine layout as opposed to what is most likely mercedes’s solution, the front engine. And then as mentioned before, aeronautics holds. A lot of nuggets of wisdom and a lot of technology pieces you want to adopt. So you won’t send out people like Ka Kitty to snoop around what’s going on in aeronautics and at the universities that still teach that there wasn’t too much actual building and designing going on after World War.

’cause of restrictions by the Allied forces. So what can you expect reasonably from Mercedes-Benz? Well, we know the company wanted and did indeed, uh, recover from the ashes. There was a lot of rebuilding going on because Mercedes had a very loyal workforce and a lot of people that had [00:18:00] survived World War II went back to remove some of the rubbles and to secure some of the machinery and repaired and to improve on it.

Uh, it’s pretty obvious that AU and Auer will stay engaged. Auer already in his sixties, you can imagine, tend to relive the old days, the glory days of thirties, and that’s why he pushed for, you know, this early engagement in Buenos iris in 51 because you thought, Hey, we have the goods still here, and why don’t we just refresh a little bit when we.

Uh, had been successful with, I think Rudolph, by his nature, was more interested in a clean sheet design and be more in the times then rather than looking backward. What you know about Mercedes is they are very methodical in their development. They’re not just going from the drawing board quickly to the foundry.

And to the machine shop and then assemble and go to the racetrack. That’s not their way of doing things. [00:19:00] They will work on components, test the components to death, assemble the components to subsystems test again in the lab, the systems and subsystems to death. When that all works out, then they have a car, and then they will also test it first on a lab with a rolling surface.

And before they ever hit the tracks, they will know a lot about the vehicle and its capabilities, and then they will go out to the track finally. And then there’s only small modific. Necessary some tuneups. And this leads to a situation, this is one of my rocking horses here that I like to think about and talk about, and that’s the evolution strategy as it applies to, uh, technical systems and developments.

The speed of progress. You can say it depends on the mutation size. How much do you change you? You start typically with some known platform, state of the art, and if you do very little, there’s [00:20:00] practically no progress. If you move on, you get onto a pretty steep curve of rapid progress. And, and there’s certain window within you can operate.

If you’re too low here with two small steps of improvement, you’re not accomplishing much. If you’re going overboard, you end up here, you end up in a alia situation or in, um, a Monaco TRS comes to mind in a freeboard design of a, uh, grand Prix car, which was basically a, an airplane without wings. You know, the, there was a, uh, a radial engine at the front.

It was. Hanging over the front exel and mass distribution was something like 70% front and 30% rear, which is a recipe for disaster. Of course, you don’t have to be a specialist in engineering to see that. So that was a design that fell somewhere into this part of the, uh, evolution window. Clearly overshot.

You want to avoid that. Mercedes was more in this conservative pioneering mode. [00:21:00] Some people have characterized the company as. Conservative pioneers, they’re going for progress. One example would be that we learn in real history later on, you know, they go from carburate to fuel injection and it’s an incremental improvement, but it’s one that’s solid and it brings some progress.

It’s very measurable, but they wouldn’t go completely to a rotary engine or something right off the bat. There will be a tight budget. Don’t expect any state subsidies or payments. Directly or indirectly, because Germany didn’t have much surplus to throw around. They had hardly been able to cover the basics.

But there would be technical inputs, of course, from suppliers that Mercedes had a tradition working with like Porsche Continental and then the fuel supplier. It was important too because the fuel in those days was free. Formula didn’t prescribe commercially available gasoline. You could brew your own mix, [00:22:00] which they certainly did.

And then there was of course the engineering force within the corporation. You could always ring up a colleague or meet over lunch and get some inputs and so on. So there was quite a bit of intellectual property and capability there. Now Mercedes obviously lost the uh, local nemes. Out on Yon, there was no chance that out on Yon would get back racing.

They hardly survived and they were cut into two pieces. One in East Germany and one in West Germany, or one in the Soviet zone. The other one in the American Zone. Uh, so there was no chance for that. So when they did something, it, it would have to have some benefit for their serious production side of the business.

And so it’s very likely, very probable that they would stick to the front engine because all their commercial. Products would be front engine taken a little dive via Edmund MLA in the 1920s. The, um, say this or [00:23:00] the Bens our age var, but that didn’t last very long. And so very unlikely that they would make a jump that would to them look like going.

Potentially, uh, down the drain, they would probably hang onto the swing AXLs or pendulum AXLs because that was also their bread and butter product. Now, one would expect that they would modify this thing a little bit because we know swing AXLs and we’ll get to that in a moment, are not the ca meow for Good Road ho.

So a case in point for all this, looking more toward what they have and what they want to commercialize is the uh, W 1 94 project. This 300 SL first generation, that’s an excellent model to study. If this case for this question that we have in front of us here, you see this? AU on the 300 representative car and very luxurious and expensive and a dream car.

You know, for most Germans, it was totally an Tanium, and yet [00:24:00] it showed, you know, we’re back again and that would be the basis for this sports car that would go race. So they had an engine and they had to live with this engine because unlike Italians, they didn’t jump right into making five different engines.

Very quickly, they stuck with the block and with what they had to work with rather than tooling up very quickly. I’m amazed, and some people have written with amazement and with appreciation that, for example, designed 25 engines in five years, which was nuts for a small company like that. Mercedes had this one engine.

Which was already an overhead camshaft engine. So a good start, but it was heavy, a boat anchor if you want. So it had to be augmented with other designs that were within the realm of possibility. And one was obviously aerodynamics. And that brings me to this image here, because in 1939 when the, uh, Italians, when they thought they were smart in prescribing, [00:25:00] that the uh, grand Prix of Tripoli was for water tourette.

Cars instead of regular concrete cars. They thought, well now our feas will have a good chance to win this race. Mercedes, at that time when they still had the pockets designed, the purpose built W 1 65 and sent to cars to Tripoli and, and ended up one two. But during qualification, they had to learn the better lesson that a four cylinder Maserati with a streamlined.

Body work got the pole position. It was faster than the Mercedes cars. Unexpected in a way because the engine was clearly inferior. So I think they must have gotten a bit of a lesson there that, hey, we have to look at the, uh, drag reduction and, and so on. Also, again, to, um, study subsystems and obviously roof came up with the, uh, space frame.

Concept, a very light frame to offset the high weight of the engine, but it was an unknown quantity and not many people [00:26:00] have had built these types of delicate space frames. So they built a very quick mule car to test this concept early on before they ever went too far down the pike and designed this final 300 sl.

Super light, but they did. And then to reduce the drag coefficient and to reduce the uh, frontal area, they angled or tilted the engine at about 55 degrees from horizontal to simply reduce the hood height and thereby increase there speed. And here you can see Charles Faru and Alfred Auer looking into the engine bay of that final product at the mall.

So continued lessons to be learned from this. First of all, you learn Mercedes. They don’t go full four out and design everything from scratch. On the other hand, they’re willing to stretch the envelope, you know, to design solutions. Again, somewhat dictated of course by the space for want to have a deep [00:27:00] door sill and threshold.

They came up with the first iteration of the. Following doors that just reached down to the lower edge of the window, and you had to kind of wiggle yourself into the driver’s. When it first got to the Elia in 52 with this scar, the, uh, inspectors were a little bit. Leery to accept that as doors and, and so it was a test for the subsequent LA Mall array, and I think they got into the lia was this type of door, quote unquote, later on for lamo.

They changed it to the tall wing doors as we know them today. And that was in reaction to and knowing that they would. Meet less leniency with the French authorities and with the Italian authorities. Of course, in those years we’re talking 1952, they also experimented with something that was a little bit out of the ordinary and a little bit advanced or too advanced for Mercedes.

One could say this [00:28:00] aerodynamic brake system. Some people will argue that was mostly shown during the time trials to confuse irritate competitors. It was never meant to be really used in racing. This was a little flimsy and it was taken down before the race began. But we also learned from this development that Mercedes was willing to accept imperfection.

For example, when you look at the engine compartment, it has no ventilation. There is no way to get the air out in an ordinary or in a very optimized way where you help reduce overall drag. They fix that later on by having some openings, yet the side, but not in this first generation of the, uh, 300 ssl. So that was one, and then they stuck to this somewhat questionable.

Pendulum rear suspension. Nevertheless, they were victorious in LA Mall and then particular at the car Pan Americana, which was quite an achievement for something that was built from bits and pieces [00:29:00] that were originally meant for a luxurious car. Working. On the other hand, what learned from there for the on automobile team is we prefer chassis over engine power battalions.

Typically, were interested in, for Ferrari in particular, the race car was a big engine, very powerful, and the rest was just a means to move forward. Chassis was never really his. Preference in those days, at least in this case, our team will think differently and will work with Pelli closely to introduce the radial tires, which Pelli had developed at that time.

Not for racing, but for passenger car applications. Uh, sports car applications, Chira. Let’s see, 67, and we add on a competition on version of that tire. We’ll use it for our dream car. Yeah, of course. That also means the driving style has to be adapted to that. It’s not totally easy from people [00:30:00] who grew up with cross supplied tires.

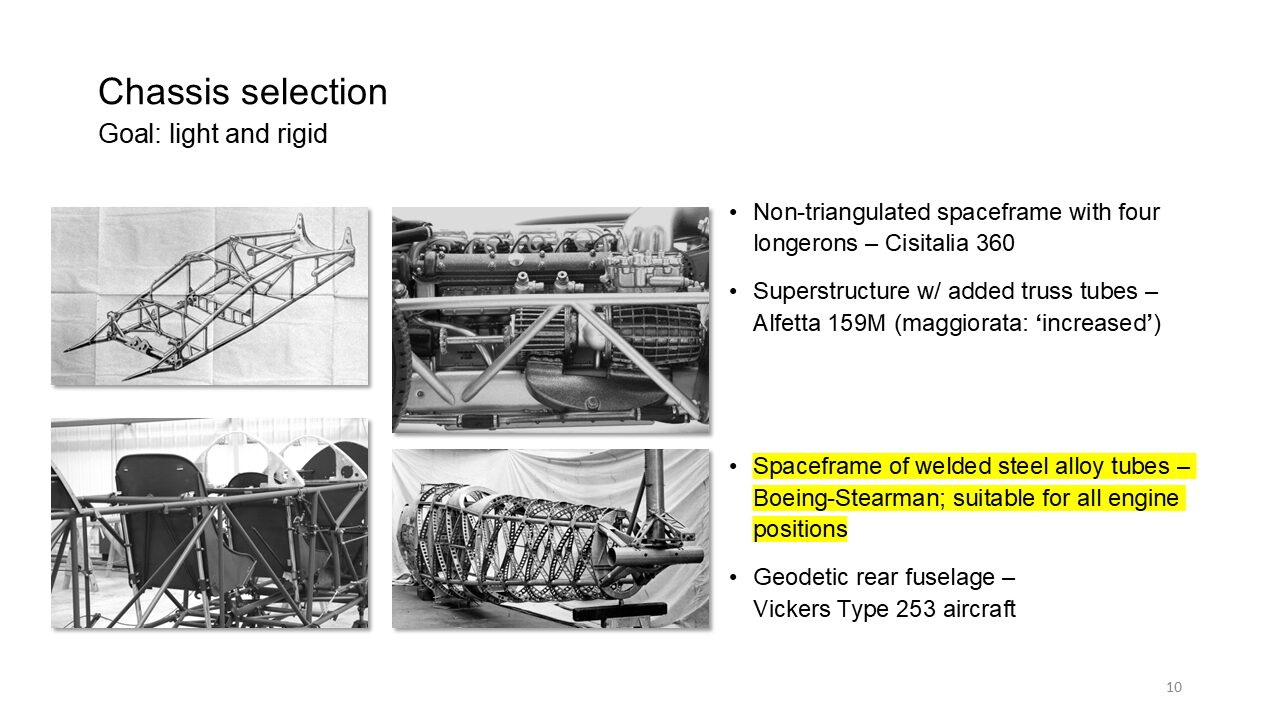

They have some difficulties and that will require also very methodical testing. Let’s look at other components that are important. The chassis frame itself is very important ’cause you want to have a very stiff chassis, and the flexibility has to be in the suspension system and not like letter frames or the frame itself was the spring system for most parts.

We have some lessons to learn from Alia, for example, but this Porsche design very strangely has this space frame, but it doesn’t make use of triangulation. You don’t see that any of these, uh, square gaps are broken up with some triangulation. Very strange. I’m not sure. What their motive was ’cause they were not under weight restrictions.

Really, to me that seems like a half-baked solution, knowing the quality of the engineers that were involved. Alpha Romeo with [00:31:00] the feta, particularly when they ran to the end of its usefulness and modified it to the uh, 1 59, which had the rear axle had also. At least some specimens had this additional framework here.

So you see the original letter frame, oval profile here, and then you can see they already made some augmentation added basically, and upper gird and did, uh, the reinforcement between the two girders quite well, but there was only a partial solution because it didn’t have any lateral connection really.

But it was better than nothing. What makes more sense is a true 3D space frame, as you can see in some of the airplanes of the time. That’s where one of our references to aviation comes in the space frame of a Boeing Stamen plane, which was a training plane. For the most part, it gives us a good idea of spatial triangulation of the frame.

Then, [00:32:00] of course, we can even go further. But this is one bridge too far. I would argue for race car designers, you could use the geodesic fuselage of British airplanes were successful in World War II and were very immune against partial destruction. They could take a lot of damage and could still go back to the base.

You see some spinal framework here that is then cla it by aluminum or fabric. Whatever the material of choice was. This is a little bit too much for race car. It’s also not as easily scaled down from the airplane size to the car size, so this is a more likely and more successful solution. This could be foreshadowing of Mono Cox structures, but again, that’s one or two bridges too far for the time.

Keep in mind, race car designers are also people and they work and concern themselves about their daily lives and their continuation of their careers. If they go too [00:33:00] far away, it goes back to that evolution function. If they veer out too far from the known. They risk that they have a big failure, and having a big failure with something that’s a traditional design is tolerable.

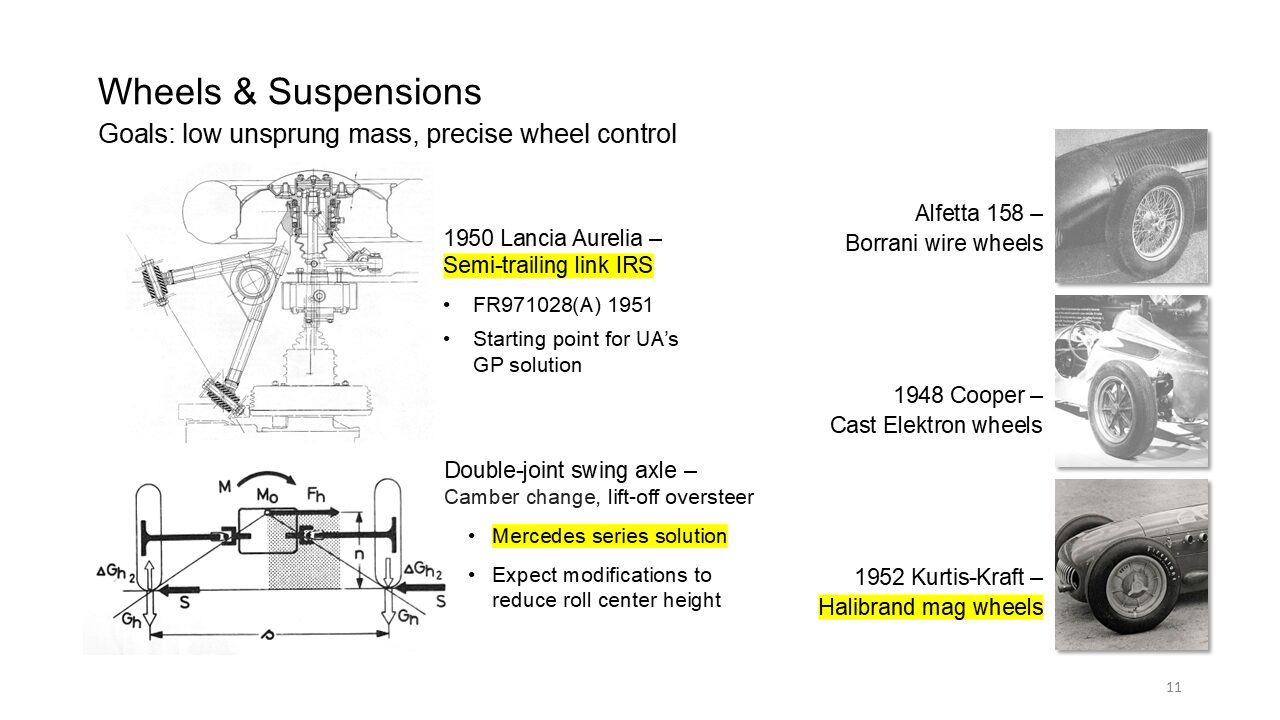

You can always say, well, everybody else did something like that. If you risk and stick out your neck too much with something that’s totally unique. And it fails everybody and their brother will say, well, you shouldn’t have done that. Right? Could be a career modifying event, but we’re talking about wheels and suspensions.

Let’s start with wheels. First state of the art were wire wheels, and particularly Bani was one of the favorite suppliers for that, but that was also a fairly flexible wheel, and it needed tuning and adjusting and maintenance. Cooper early on after World War ii. Changed over to cast electron wheels, and part of the reason was that it was easier to get aluminum mag magnesium in England after [00:34:00] World War II than steel still was rationed and a lot of aluminum was found from war efforts and equipment.

So that was one thing. And it was also good for Cooper spare part business. It was a an OEM wheel that couldn’t easily be replaced as something else. But more importantly, in the US Heli, brandand had introduced already and proven the, uh, magnesium cast wheels machined then to fit, and that won the 1952 in the 500, and it became commonplace.

So I’m wondering why people in Europe didn’t look at those. Developments and said, Hmm, there is an advantage here. We save some unsprung weight and we get a more rigid product. That is obviously proven on high speed oils. And then let’s look at suspension systems quickly. ER had already introduced with the first generation of the aurel, a semi trailing [00:35:00] independent rear suspension, uh, which you can see it.

Top view of here would be the a coil spring and the attachment points to the chassis, and it’s the drive shaft the wheel. So this would be a start, we think for. Uh, development for an optimized rear wheel suspension, independent suspension. For a race car, it has its pros and cons as well, but you can play a lot with the different angles and orientations of components.

You can do that in 3D and get some reductions in tow, in and in Canberra. Change with the, uh, spring deflection. So there’s probably something to be found. Now we assume that a Mercedes must stick with the pendulum axles, maybe in this format, but it, it’s the one that gives you the highest roll center, and that’s not very popular really for race cars.

You can really get to the point where you check up the one wheel and it leads to [00:36:00] instabilities. You have pretty steep kember angle changes. It’s not the best thing for a race car, so we assume that it as well modify that you try to make the, uh, pendulum lengths as long as possible. So you could do something that goes underneath, uh, could even to the opposite side, and you could crisscross the links there.

So I would expect they’re putting myself into it. 1952 that it would work on some of this stuff. And what we see here is an interesting car from New Zealand and it dovetails quite well with people that came back from World War ii, had aircraft experience where aircraft mechanics, a couple of folks in New Zealand built their own car.

They had studied and read about the Aon. Mid-engine configuration and they said we can build that too, and we can go to the scrap yard or to the, um, auction places where you can buy cheaply. The surplus [00:37:00] from the army and from the air Force, and that’s what they did. So they built their own interesting car and it had a very low pivot swing axle arrangement, which is shown here in a, in a picture of the renovated or restored version of this car here.

This is, looks almost like it’s over restored, but it’s interesting. You see very long arms of this swing axle. They almost merged to, to a single axis of rotation down here, very low. And they also pilfered some Lio struts from airplanes and used them as spring and damper. Very innovative and very interesting.

Car. Not too much is known about this. RA four vineyard, which worked with a four cylinder standard Vanguard engine, slightly supercharged, and it had 2088. C. So it was a formula Lire car and didn’t qualify for a Grand Prix, but it was pretty much [00:38:00] only raised in New Zealand, but it has been restored in England and it will come to a couple of events in Florida.

One is uh, Moda Miami and the other is Amelia. So you will see if you get there, you will see the sky in real life. And can see more than from these pictures, but an interesting way that tinkerers worked on something that made a lot of sense and they had a lot of fun with it. One of the mechanics was then the driver, and he managed to participate at Lady Wig Ram Trophy runs for several years was modest success.

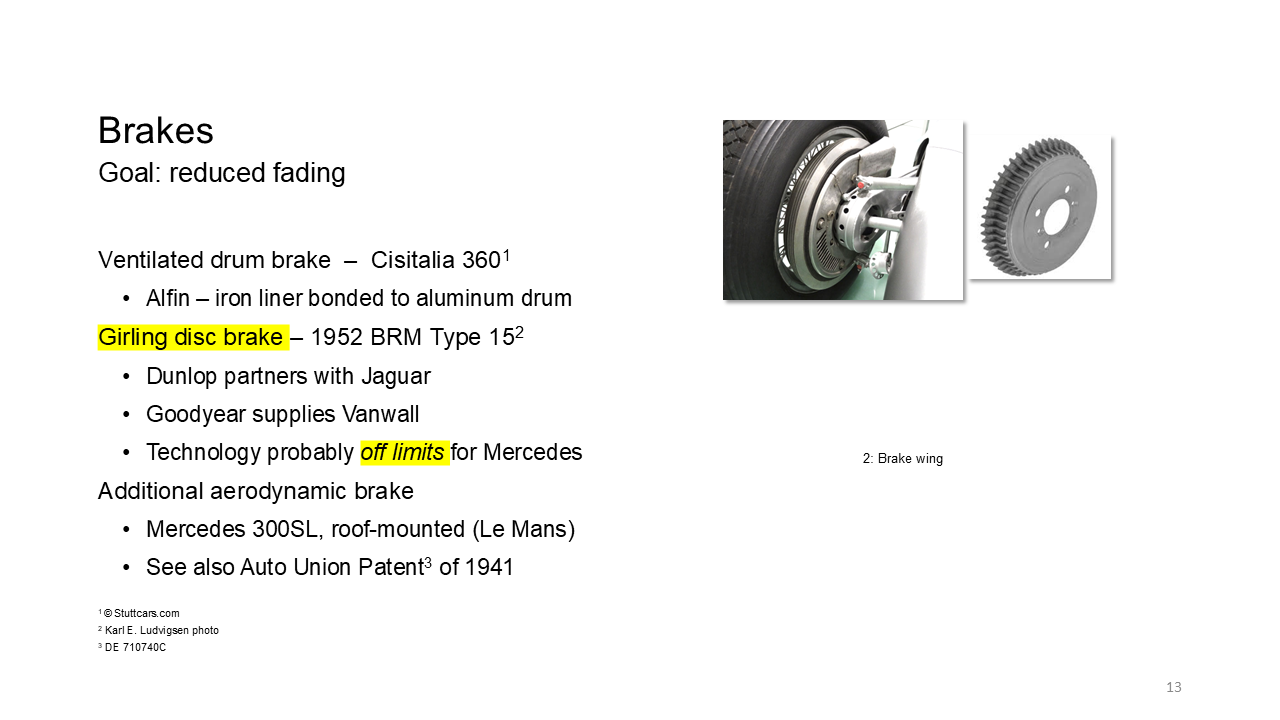

Brakes of course are important for the race car. What can you do there? Obviously, ventilated drum brakes were the industry standard fin processes were often used to bond strongly and have a low thermal resistance between the iron liners and the aluminum body. With fins, different shapes of fins. [00:39:00] But by 1952, disc brakes became already a possibility for race cars.

And again, that’s a technology that comes from airplanes. Yeah. During World War ii, a lot of airplanes, British American used already a form of. Disc brakes and there were several manufacturers. Dunlop was one of them. Dunlop worked with Jaguar on, on sports cars and growing with BRM and got that to science already.

And then, uh, Tony Derval, who had already started his own activities with the thin wall specials that I want also to have the latest technology in brakes. And he worked with Goodyear and got some disc brake systems there. But we can assume that that technology was off limits for Mercedes. I cannot imagine that any of these companies, particularly Dunlop, that helped Jaguar, would also help Mercedes to beat the snot of Jaguar.

I think that was off limits, and I think Mercedes understood that. And so they were. [00:40:00] Working with these aerodynamic breaks that we saw already, this roof mounted effort. And there’s also a, uh, patent that was issued to Auto Neon in 1941. Fortunately, that image didn’t make it, but it’s a German patent that was issued, and that shows an aerodynamic break, basically a wing that you can flip up with.

Server power from the engine and assist in braking, probably tailored to those records trips that people made on the auto barn, but it could be used in Grand Prix racing as well. There was nothing. That would prohibit that Anyway, that would be one way to get around the, this great embargo that I would think was prevalent.

The other thing is driver position is one thing, particularly with the front engine car, the typical bomber seat, you know where you sit pretty upright, like in an arm chair or the chairs you’re sitting on, the driver. Sits very upright and provides quite [00:41:00] an obstacle to the aerodynamic profile. And fortunately, this picture came across here and that is in, uh, what is called Zenger.

He erased this thing that was. Based on the Volkswagen 64 or Porsche 64 project, got one. You know, he was an Austrian, so he was close to the Austrian Porsche office at the time. So he got one of these, uh, 60 fours, which they were intended for the, uh, Berlin, Rome long distance arrays. That never happened, if I recall that correctly.

So he got that and you have to consider and had a, a pretty severe motorcycle accident. So his right arm was not useful to him and he needed to be able to lean on the steering wheel when he changed gears. So he had a shifter on left hand side. And he leaned forward on the steering wheel to shift gears.

So it was a bit of an aberration. He needed that kind of seating position. But you can see [00:42:00] here it’s unfortunate. It’s, uh, not the optimum solution when you have a rear engine or mid engine. In our case. On the other hand, what we learned from aeronautics, and particularly from glider planes or sail planes, there was a development going on at the, uh, polytechnic in terrain in, uh, 1953 in particular, there was a new Chro d Olo Avela that was founded, and it was kind of an operation in the corner of a lab first.

But the, uh, team there wanted to change the whole composition of sail planes. ’cause in sail planes, they have no engine. Obviously you need to have a very low frontal profile. You need to have very low drag coefficient. And what they introduced was a leaned backwards position of the pilot. It’s almost a position like you find in or found then in the, uh, say the low grand Prix cars, particularly the [00:43:00] monocoque versions, you know, and they could also beef that up with, uh, some scientific investigations.

I have the source given here that there are optimum angles for body parts. And they’re not 90 degrees. And so the upright sitting position is not necessarily the best, particularly if you don’t have to have high steering forces to work with, which was one of the reasons why people set so upright or why NASCAR drivers also hang on close to the steering wheel, at least the past.

But in the case of a front, well of a, um, car with mid-engine, there’s not much load on the front ax. Excellence of the steering effort, it’s much lower. So you can get by with this more relaxed. Leaned back sitting position and it’s now a standard practice of course in sail planes. But in 53 that was something that was, was pretty new, in fact it was unheard of.

And people were wondering, can the pilots do that? And they had some test flights and they felt, Hey, this is great actually. And so, [00:44:00] uh, we sent of course Kalo Kitty around different universities. Naturally he has to go to, to and to Milan and understand what’s going on there. And so he comes across this and the innovator and the young man who wants to make his place in the history comes across this and says, Hey, why don’t we experiment with that and reduce the frontal area of foreign Grand Prix.

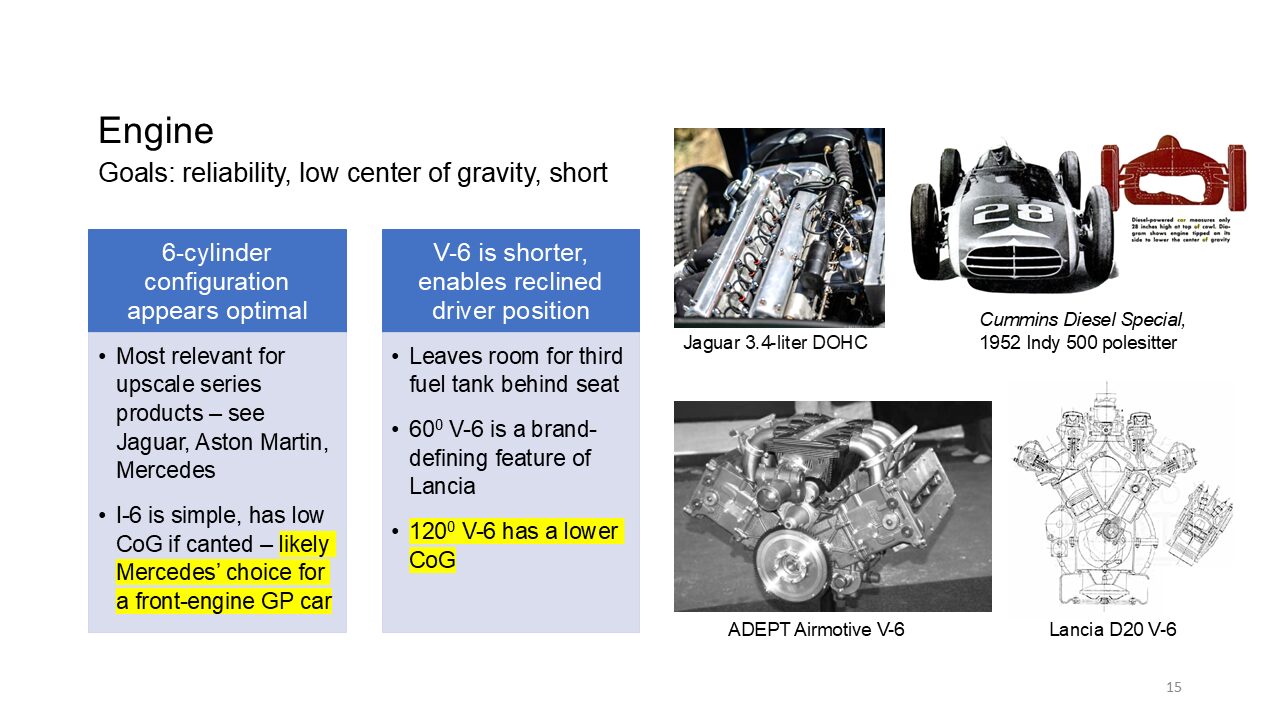

And that goes on with, with engines also quickly talking about different engine choices. It seems quite reasonable for the two and a half liter formula, first of all, that it shows the, uh, naturally aspirated one and the, uh, supercharged version that was allowed at 750 cc. The penalty for supercharging was just too high.

So you look at the 2.5 liter engine and you ask yourself, how many cylinders do you really need? You need 16 cylinders or 24 or or four, maybe six is a good compromise. Very likely [00:45:00] because you can see Jaguar was very successful. Was there six cylinders? Mercedes had just proven, uh, with the, uh, 1 94 project that, hey.

We can win the races and championships with six cylinder engines. And of course, they had slammed it at Mercedes, their engine. That was brought to an even more dramatic fact in the Cummins Diesels special of 1952 that participated in the Indy 500, and there was Freddie Cummins desire to prove that diesel engines could be very successful in any application, including race cars.

So you built this special. Car with the Watson chassis, elongated and modified in many ways, but he chose to tilt the engine practically by 90 degrees. So the crankshaft is about here, and this is the cylinder head. Now this was, uh, overhead valve engine, as I understand it was turbocharged and it was, was tilted for minimum front area.

So you could think Mercedes should think [00:46:00] about those lines as well. In our case here for mobility, we say, well, Landa is really our flagship brand and it relies on V six engines to a great extent. Why don’t we also make our racing engine just like, say that D 20 V six lunch here that they had already at a 60 degree cylinder angle.

Makes good sense. It’s a short engine. It allows more space for the reclined driver position. So let’s do that. But maybe we should change the angle as. The Vergilio had proposed you can do that 220 degrees to make a shallower engine. So I put in this image here, which to be honest is not from the time we’re talking about this, uh, a more recent South African aircraft engine, and it’s a 120.

Degree V six cylinder engine, just to show you what the, the form factor would look like. I think that would give a pretty optimal [00:47:00] configuration for a, uh, mid engine configuration that minimizes the frontal area and the, uh, a drag coefficient. That’s it. So we assume that Mercedes will do this and, and use an inline six system, which we can’t know at the time that that was the wrong assumption.

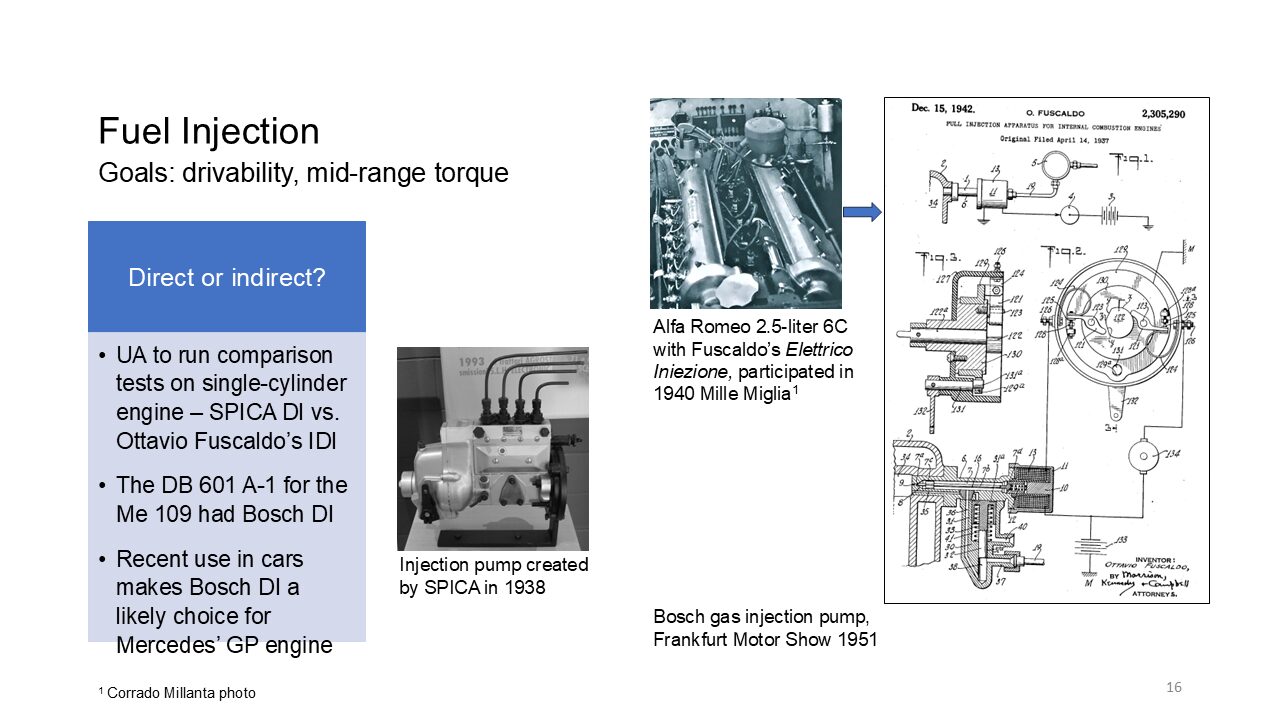

Uh, I can live with that. And fuel injection is almost inevitable. And the, um, question is, can you even go as far as direct injection into the combustion chamber, or do you allow for an indirect injection ahead of the, uh. Inlet valves. Mercedes obviously had some experience in the, uh, DB 601 aircraft engine of World War II with direct injection, and we know that Schonberg, who was the engineer involved, was parked at the time, still at a small company.

Mm-hmm. Called Good Broad until he got through his deification process and then could join Mercedes again. [00:48:00] Very likely that he would push for an adaptation of this kind of injection. On the other hand, Italy had quite a lot to offer in terms of indirect uh, injection. Fellow Avi Fudo had patented the application in in 1937, a solution for.

A very smart electrical injection. Very much like most cars that we drive today have their injection system and no electronics obviously. ’cause that wasn’t invented yet, but the basic makings were already there. And this thing raised in the, uh, Elia of, uh, 1940. There was an alpha Romeo, two and a half liter six C equipped with this type of injection system.

And it ran on a mix of palm oil. I understand. And some other non-conventional fuel component. ’cause that was when Italy was in this archy. Mode and couldn’t import a lot of [00:49:00] mineral oil. And so it was a, a theme that fit into the landscape and it, it demonstrated and also in a gera motorbike, as I understand that the system worked quite well.

It got forgotten for quite some time, but you could see electromagnetic injection valves here, actuated and timed by a distributor system. Very much like your time, the ignition. So it was not a continuous injection. Like say the Hillborn system in the US would’ve been. So that’s basically what we decide, or we leave it to the engineering team.

Do they want to go with a speaker direct injection that they also have at their disposal within for Mayo, or when they go with something like this indirect injection. So then we say our, our special source will be the emphasis on aerodynamics and we want to create downforce. And we saw this picture of the TAD yesterday that was explained to us.

You can see the fellow who was behind it was a, uh, who was behind [00:50:00] the patent that you see figures from here. And you can see that he not only had side wings, but he also had an elevated wing with end caps and all the makings of a modern aerodynamic concept. So we put all this together into a final product and we think we can beat Mercedes.

On a good day, not always, but on a good day.

Thank you, Carl. I think we have some questions.

Don Capps: My thing that strikes me always when you have these discussions, why wasn’t this sort of analysis carried out then? It’s very capable. Everything’s there. Mm-hmm. So why was the contemporary thinking not along these lines? Because it’s, I know it is just retroactively.

Yeah. But all that was available then.

Karl-Heinz Mertins: Yeah. And I limit myself particularly to the availability of technology bits and pieces. [00:51:00] In hindsight, it’s very easy to throw in electronics, for example, which wasn’t available then. But a good answer of that is. I think I mentioned it briefly, people want to survive in their organizations, right?

And for example, if you’re in it, at least in the time when computers first came up, if you specified IBM computers, you were home free. It didn’t matter that they were not as functional performance wise. They may have had bad service whatsoever, but it was IBM. And so if you were issuing the purchase order for IBM computers.

You survived easily, even if things fell by the wayside, if you would’ve specified some more exotic, more powerful computer and it would’ve given you difficulties. Everybody points at you and says, you, why did you do that? You know, how could you do that? So it’s always safer to stay with the incumbent solutions, and it takes [00:52:00] risk.

It takes the right personalities to venture out a little bit. And with this. Evolution window, you have to be really careful not to go too far out and and fail. So I think there’s more incentive for playing it safe than being too daring. And there’s a herd mentality. So if everybody uses Webber Carburetors in rating, why should I do something different?

Right? But if you want to beat the other guy, as I mentioned, you cannot out Mercedes. Mercedes, don’t even try it. You have to do something different and you have to take the risk and to be willing to risk. I think Iran Horst had demonstrated it throughout his career that he was willing to do that. Thank you, Carl.

Thank you.

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research [00:53:00] Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports. Spanning Continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike. To share stories of race drivers race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records. [00:54:00] Print ephemera and images to safeguard as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org.

We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, [00:55:00] additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 The Challenge of Beating Mercedes-Benz

- 03:01 Mercedes-Benz’s Post-War Comeback; The 300 SL and the Marshall Plan

- 08:59 The Shift to Mid-Engine Layout

- 12:28 The Italian Engineering Dream Team

- 18:45 Mercedes-Benz’s Methodical Development

- 26:43 Lessons from the 300 SL

- 29:04 Chassis Design, Radial Tires, Space Frame and Aviation Influence

- 33:26 Innovative Suspension Systems

- 38:39 Brakes and Aerodynamic Innovations

- 40:43 Driver Position and Engine Choices

- 47:20 Fuel Injection and Aerodynamics

- 50:29 Concluding Thoughts and Acknowledgements

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

Enter UNE Automobili: A Fictional Challenger with Real Engineering

Karl’s imagined Unione Automobili draws inspiration from Auto Union’s pre-war mid-engine designs and Italy’s fragmented post-war automotive landscape. The proposed conglomerate includes storied marques like Lancia, Alfa Romeo, and Iso, unified under an Italian-state holding company. The goal: to create a technically superior, mid-engine Formula One car capable of challenging Mercedes on merit.

Engineering the Advantage: Chassis, Suspension, and Tires

Unione Automobili’s (UA) strategy hinges on exploiting Mercedes’ likely adherence to front-engine architecture and swing-axle rear suspension. Instead, they opts for:

- Mid-engine layout for optimal weight distribution

- Radial tires from Pirelli, offering superior grip and reduced rolling resistance

- Space-frame chassis inspired by aviation triangulation, enhancing rigidity without weight penalties

- Semi-trailing arm rear suspension, allowing fine-tuned camber and toe control

Aerodynamic downforce also takes center stage. Inspired by wartime aircraft and early patents, UA explores elevated wings with endplates and integrated airflow management—decades ahead of their mainstream adoption in F1. Drawing from glider design and sailplane ergonomics, the engineers propose a reclined driver position to reduce frontal area and aerodynamic drag. This innovation, borrowed from the Polytechnic of Turin’s 1953 sailplane experiments, anticipates the low-slung cockpits of future monocoque racers.

While Mercedes likely sticks with a heavy inline-six, UA embraces a compact 60° V6, honoring Lancia’s engineering legacy. The team even considers a 120° V6 layout for reduced engine height and improved packaging. Fuel injection – either direct or indirect – is a given, with Italian patents from the 1930s offering viable solutions.

Strategic Engineering: Know Thy Enemy

Unione Automobili’s approach is not just technical – it’s philosophical. Quoting Sun Tzu, Karl emphasizes in his lecture, the importance of understanding Mercedes’ methods to anticipate and counter them. Rather than mimic Stuttgart’s strengths, UA seeks “unfair advantages” through differentiation, they key being: mid-engine layout, advanced suspension, and aerodynamic innovation.

While this alternative history remains speculative, Karl’s is grounded in real engineering principles and historical context, and he challenges us to think critically about innovation, risk, and the evolution of motorsport technology. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the best way to win isn’t to follow the leader – but to redefine the race.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)