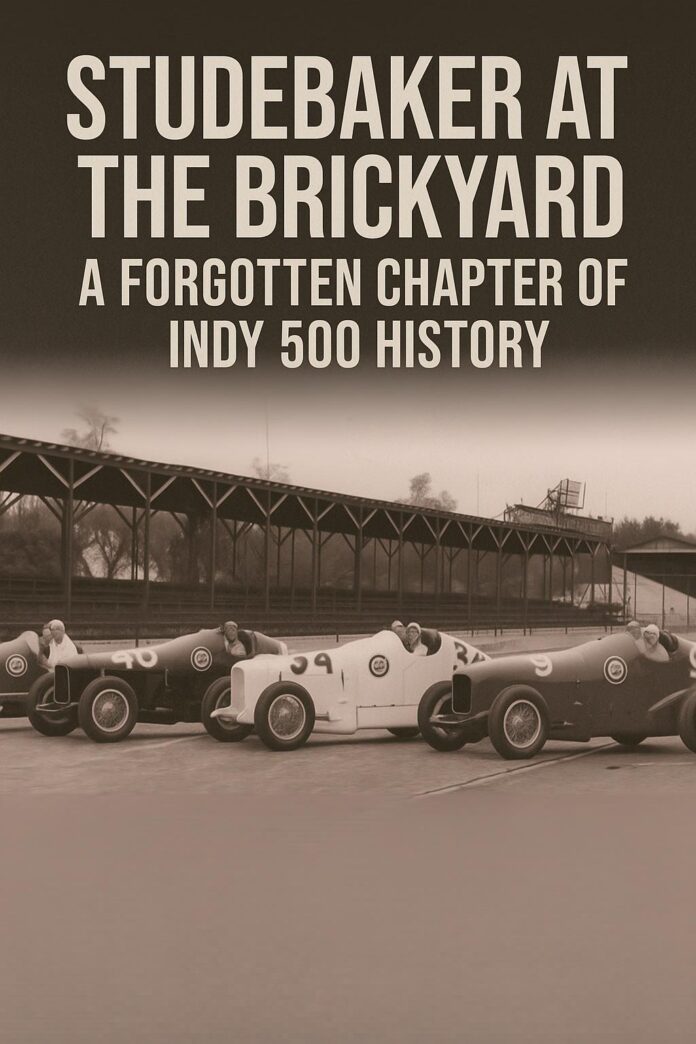

When you think of Indianapolis 500 legends, names like Duesenberg, Miller, or Offenhauser might come to mind. But tucked away in the annals of racing history is a surprising contender: Studebaker. Known more for its solid middle-market cars than for motorsports glory, Studebaker made a brief but fascinating foray into the Indy 500 during the early 1930s – an era defined by innovation, grit, and a touch of corporate bravado.

Studebaker’s founders were no strangers to speed. In 1881, the Studebaker brothers famously raced horses down Lafayette Street in South Bend, Indiana – earning a fine and a place in local lore. That spirit of competition lingered as the company transitioned from wagons to automobiles, dabbling in early racing with EMF and Flanders models before stepping back to focus on reliability and reputation.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

But by the late 1920s, Studebaker was ready to re-enter the fray. The introduction of the President 8 engine in 1928 – a robust inline eight-cylinder powerplant – marked a turning point. Studebaker began endurance testing at Amatol Speedway, logging 30,000 miles in under 19 days and proudly proclaiming, “Nothing on Earth has gone so far, so fast.”

The 1930 rule changes at Indianapolis opened the door for production-based entries. Studebaker engineers seized the opportunity, fielding the Rompthie Special and the Russell 8 – both powered by modified President engines. Though not factory-backed initially, these cars showed promise, with Snowberger’s Russell 8 finishing 8th in 1930.

By 1931, Studebaker was all in. The Hunt Special, a stealth factory project, joined the grid alongside returning entries. Snowberger stunned the field by taking pole position, proving Studebaker’s engineering chops could rival the best.

Spotlight

Andrew Beckman has been with the Studebaker National Museum since 1999 and currently serves as Archivist. He previously worked at the Sheboygan County Historical Society in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and the Wade House State Historic Site in Greenbush, Wisconsin. Mr. Beckman hails from Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and holds a BA in History from the University of Wisconsin- Green Bay. In 2004, he completed the Modern Archives Institute at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. In 2009, he earned his mid-level certificate in Collections Preservation from the Campbell Center for Historic Preservation Studies in Mount Carroll, Illinois. Mr. Beckman is the author of The Studebaker National Museum: Over a Century on Wheels, and Studebaker’s Last Dance: The Avanti, and is a columnist for the Studebaker Drivers Club magazine, Turning Wheels.

In addition to his duties at the Studebaker National Museum, Mr. Beckman is a member and Past President of the Society of Automotive Historians. He also serves as a commentator for The Henry Ford Museum’s Motor Muster and Old Car Fest.

Synopsis

This episode of The Logbook, our History of Motorsports series, explores the history of Studebaker’s involvement in the Indianapolis 500 car racing events during the early 1930s. The presentation recounts Studebaker’s brief but significant presence in motorsports. Andrew Beckman from the Studebaker National Museum delivers detailed accounts of the development and performance of Studebaker-powered race cars, focused on the company’s efforts in the 1932 and 1933 races, as well as the ongoing impact and legacy left by these vehicles. Beckman also discusses the technical development of the cars, the challenges faced by Studebaker due to economic constraints, and the eventual disposition of the race cars. The presentation is heavily informed by Studebaker’s corporate archives, museum collections, and contemporary race accounts.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

[00:00:00] Brake Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family.

Studebaker at Indianapolis. While Studebaker is rarely the first name one thinks of when discussing motorsports, the company had a strong yet brief presence at the Indianapolis 500 in the early 1930s. Studebaker laid the groundwork with the introduction of the President’s inline 8 cylinder engine in early 1928.

The advent of the Indianapolis 500’s 1930 rule changes opened the door for production based entries, and the president’s rugged eight powered a pair of private entries. These Studebaker engine specials showed promise and led to the development of Studebaker’s corporate team. This presentation will detail the origins and evolution of Studebaker powered race cars beginning in 1930, with a special emphasis on the company’s factory backed [00:01:00] campaigns in 1932 and 1933.

Additional focus will be placed on the technical development of Studebaker race cars, as well as the post Studebaker disposition of the team cars and their present day status. Sources include Studebaker’s corporate archives and image collection at the Studebaker National Museum, plus period publications and race accounts.

Additional data is drawn from secondary sources profiling the Studebaker team, plus owner research compiled during their stewardship of the cars. Andrew Beckman has been with the Studebaker National Museum since 1999 and currently serves as archivist. He previously worked at the Sheboygan County Historical Society in Sheboygan, Wisconsin and the Wade House State Historic Site in Greenbush, Wisconsin.

Mr. Beckman hails from Manitowoc, Wisconsin and holds a BA in History from the University of Wisconsin Green Bay. In 2004, he completed the Modern Archives Institute at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D. C. In 2009, he earned his mid level certificate in Collections and Preservation from the Campbell Center for [00:02:00] Historic Preservation Studies in Mount Carolina, Illinois.

Andrew Beckman is the author of the Studebaker National Museum, Over a Century on Wheels, and Studebaker’s Last Dance, the Avanti, and is a columnist for the Studebaker Drivers Club Magazine, Turning Wheels. In addition to his duties at the Studebaker National Museum, Mr. Beckman is a member of and past president of the Society of Automotive Historians, and he serves as a commentator for the Henry Ford Museum’s Motor, Muster, and Old Car Fest.

So we will begin our final afternoon session with Andrew, who’s going to be discussing Studebaker at the Speedway, so please welcome. Andrew Beckman. Thank you for having me today. It’s my first time out here at the conference in general and also my first time to this part of New York. It’s absolutely beautiful to answer Kip’s question.

He asked me beforehand. Yes, Studebaker did race at the Indianapolis 500. So you’re gonna have to stay for the whole thing now. I’m sorry. We’re merely conducting an exacting test of our cars stated a Studebaker executive on a fine spring day in 1933. The executive was Studebaker’s [00:03:00] chief engineer, Barney Roos.

He was standing at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in front of the team of Studebaker race cars. His full quote was, as was our policy last year, Studebaker is not trying to win the Indianapolis race. We are merely conducting an exacting test of our cars. He went on to say he had a bridge to sell you in Brooklyn and he also had some land in Florida you might be interested as well.

For if anyone believes that anyone entering a race is not trying to win, well, certainly wouldn’t lend them any money. Now, Studebaker is, I realize, not the first name that comes to mind when you speak of motorsports. In fact, it’s not even the first name that comes to mind if you speak of motorsports from South Bend, Indiana.

Thank you, Ryan Newman, for that. But Studebaker, for its 114 years of vehicle manufacturing, had a very limited but very intense period of motorsports competition. Now this is somewhat of a surprise. You would think maybe the Studebaker brothers, the company’s founders, had something against motorsports. No, this was not the case.

In fact, Henry and Clemens Studebaker were avid horsemen. J. M., all the brothers, loved a fast race or so the day. In fact, in [00:04:00] 1881, J. M. had just acquired a new mount, and he felt that his horse was faster than his brother Clem’s. His brothers are wont to do. They took exception to this thesis, and they decided the only logical thing to do was to settle this on Lafayette Street in front of the Studebaker administration building in South Bend, Indiana.

Unfortunately, they passed by a local town marshal who immediately cited them for speeding and forced them to appear before the chief magistrate, who was also the mayor of South Bend. Despite a full throated defense of their actions, they were fined 2 in course costs and furthermore agreed never to do it again.

Again, if you believe that, well, I wouldn’t put too much stock in that. As Studebaker transitioned to the automobile age, the early Studebaker automobile history is not one of just building automobiles out of the Studebaker factory. They were essentially marketing cars produced by other upstart companies.

After all, Studebaker had the name recognition. They’d been around since the 1850s. They were the worldwide leader of horse drawn equipment. The new EMF models for Everett Metzger Flanders. That was the larger of the two models in the Flanders 20, given for its horsepower. Those as well as some Garford models and even one of their electrics [00:05:00] competed regularly in local contests throughout the early part of the 20th century.

The EMF in Flanders down all competing cars in the first sanctioned race meet of the season on Montgomery, Alabama’s track. And of course pointing you to where you could go out and buy one of these new race proven Flanders 20 and EMF 30 automobiles. Yet despite this early flurry of activity, Studebaker really stepped back from encouraging their cars in competition.

Studebaker was really more playing off their name, again, their reputation. You could go to your Studebaker dealer, you were going to get a solidly built car, you would pay a little more for it, they certainly weren’t competing with Henry Ford in the low price field, but you could count on getting a solid, middle priced car from Studebaker.

And indeed, their reputation spoke for itself. We have a 1919 Big Six in the collection that logged 475, 000 miles. Not as a company test vehicle, but as a privately owned automobile. And Studebaker felt this was noteworthy, hence they bought it back for inclusion in their collection. The first appearance of Studebaker at the Speedway was in 1924.

This deserves a bit of an asterisk here. The Studebaker Special No. 8, driven by Earl Cooper, actually placed second [00:06:00] that year. And I will point out the Studebaker components on this car right now. That would be the decal on the side here, and also the radiator badge. This is a Miller engine, Miller chassis body.

If you’re familiar at all with, uh, Indianapolis race cars, the rules formula for that time, these were all very specialized, high performance vehicles. And let’s face it, Studebaker’s 40 horsepower, light six engine was probably not going to cut it on the field that day. And Studebaker at this period too was in a bit of a crossroads.

They had, at one time, the top engineering team in the industry with Owen Skelton, Carl Breer, and Fred Zeder. They worked for Studebaker in the late teens. They developed Studebaker’s popular Big Six model. But they had a falling out with company executive Albert Erskine. He was actually the president at the time.

And they packed their bags and headed off to Chrysler. And did very well for Mr. Chrysler and his new corporation, which debuted in 1924. Studebaker also had a problem in the early 20s of, really, one of marketing. There was a survey done of the industry at some point and it figured out Studebaker had one of the narrowest price margins in the industry.

That is, from their least expensive automobile to their most expensive automobile. Erskine realized this, [00:07:00] but he also realized Studebaker needed more capacity. They needed larger factories. So starting in the late teens up to the mid twenties, he was trying to overhaul Studebaker’s plant complex. And when that was in place, he thought about reinvigorating the model lineup.

I had mentioned the Light 6 previously and the Big 6. Their middle priced model was called the Special 6. Let’s face it, from a marketing standpoint, these are not very stimulating names. Their marketing partner got it in gear in 1927. The Big 6 became the commander and certain models became the president.

The Special 6 became the dictator. It seemed like a good idea at the time. That’s a talk for another time. The Commander, however, and particularly the Commander Roadster with the three musketeers designed Big Six engine, it was noted for being an incredibly reliable engine. In terms of its engineering style, robust would be your words.

Someone had said that Studebaker’s engineering philosophy was there’s no substitute for cast iron, and if you can’t cast a glance at one of these engines, you’d be hard pressed to dispel that. Developed a massive amount of torque. It could churn along all day, Studebaker. Actually gave it full pressure lubrication in 1924.

And with that, they saw, well, we have this [00:08:00] very rugged automobile. Let’s go out and do some testing with it. We’ll do some racing. Again, these were more private events, not necessarily sanctioned by Studebaker, but certainly not exactly discouraged by the company heads either. This is at the Amatol Speedway in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

And we see a couple of commanders right there. And of course, I wouldn’t be showing you this picture if they did not win the race. And again, the cars held together very well. You got a very rugged, a very solid automobile with the Commander Big Six. They sent three more commanders back to Atlantic City in 1928.

And the orders were to complete 25, 000 miles as quickly as possible. The commander you see right there in front, the roadster, completed that task in 23, 000 minutes. Now, 23, 000 minutes is a bit of a tricky concept to wrap your head around. Anyone good at math in here? How long is 23, 000 minutes? Put it in days.

Anyone? Anyone? I see Luke furrowing his brow. I gotta tell you, the grade schoolers I give tours to figure this out a whole lot faster than you guys do here, but, uh, it comes out to 16 days. So for 16 days, day and night, these commanders lapped, Rain or shine, through mid [00:09:00] and darkness, and it was not running time.

The clock started when they started the first mile, and it stopped when they completed the 25, 000s. It was a new record, and in fact, Studebaker proudly proclaimed, Nothing on Earth has gone so far, so fast. Now as part of Albert Erskine’s grand plans for the company, marketing the product as one end, he had to do something about expanding Studebaker’s price reach.

So with that, he acquired the Pierce Arrow Corporation in the late 1920s, I believe it was early 1928, to give Studebaker a luxury brand. He wanted to introduce a low priced model called the Erskine. Modestly named, one might say, but the Erskine VI, it had an incredibly handsome car designed by Ray Dietrich.

Unfortunately, it had that fatal flaw in the automobile industry of being both overpriced and underpowered. And the Erskine was not a success in the market, especially when this new product from Chrysler and Plymouth and Ford’s Model A came on the scene later. The Erskine really never had a chance, and unfortunately, it disappeared from the landscape just a few years later.

On the other end of the line, however, was Studer’s President 8. The President, as I mentioned, initially started as a upscale model of the Big 6 when they renamed that line. But for [00:10:00] 1928, the all new model F A President came out, and with it came a fresh engine design. 313 cubic inch inline eight cylinder engine, fresh off the drawing boards from new chief engineer Delmer G.

Barney Roos. Mr. Roos had previously done stints Marmon. He had a good engineering mind, and he was The chief engineer that Studebaker was looking for at the right time. The President 8 was really a hot performer for the day, and kind of very out of character for Studebaker’s steady yet solid reputation.

And they immediately realized they had a pretty hot car on their hands. Back they went to the Amatol Speedway with a quartet of presidents. This time the goal was 30, 000 miles, in which the roads through up front there completed in 26, 000 minutes. So that’s about 19 days. Again, Studebaker was doing things that no other automaker was equal to able.

I believe Hudson went out and did a similar test, but they counted driving time instead of actually continuous running clock last time. And you got to think Studebaker was really on to something here. Erskine, in his mind, I think he was looking at going kind of the General Motors route, a [00:11:00] car for every person purpose, really expanding into the luxury market, and expanded Studebaker’s reach and awareness, trying to really rebrand Studebaker from that old horse drawn air manufacturer to someone who’s really bringing you some exciting automobiles.

Now the Studebaker President 8 might have sounded like an ideal power plant for the Indianapolis 500, and fortunately the rules at the time were such that that engine simply did not qualify. They had a maximum displacement of 91 cubic inches. And again, we hear the names Miller and Duesenberg bandied about a lot during talk of the 500 at that time.

Thankfully, there were no restrictions on displacement for the pace cars, and Studebaker was selected to serve as the pace car for the 1929 race, and also supplied a trio of official cars as well. And here we see the Pace car, you know, festooned as one would be, so there’s no mistaking, this is most definitely the Pace car.

Anyone identify this? I know an Indianapolis figure, a name that will sound familiar, and you’ll probably go, Oh, yeah. Anyone? Well, that would be Harry Hartz. And sitting behind the wheel is, if you get this one, I’ll give you 5 right now. Miss Anita Page, a star [00:12:00] of the screen, an actress, and she was actually appeared in an Academy Award winning movie, The Broadway Melody, available on Netflix, check it out tonight back at the hotel.

Now, back when I was in high school, some guy tooled around town in his Chevy Monte Carlo pace car replica, and apparently, I’m not sure if it came with the jacket and the hat and, you know, everything else, or if he stopped at the pro shop on his way out, but, I mean, there was no mistake in that car driving around Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and of course, I’m sure a lot of you remember the pace car replicas from the later 60s, early 70s, uh, at our Concord and South Bend, we had one of the I think it was early 70s Oldsmobile pace car replicas.

This is not a new concept. I came to learn when I was putting this talk together. Studebaker commissioned 30 replicas of the 1929 Indianapolis 500 President Roadster powered by the 115 horsepower Studebaker President 8 motor. This car possesses the speed and endurance so strikingly demonstrated by its record breaking performance of 30, 000 miles in 26, 326 minutes.

They weren’t wasting a beat on promoting that achievement. One of these cars still survives today, believe it or not. It was found, it had been repainted [00:13:00] several times, and the seller had actually promoted, Oh, you know, this is one of the Pace cars, replicas, and the guy who bought it was like, Yeah, sure, right, you know, you’re trying to boost the price a little bit.

Then as he’s stripping the paint, he found the unique paint scheme that was only supplied. On those 30 cars, so it’s good to know one of those is still with us. Well, ahead of the 1929 race, there was an announcement for rules changes for 1930. In particular, displacement was up to 366 cubic inches. Minimum weight was established, I believe it was 1, 750 pounds.

The riding mechanic came back and a few other choices to really open the door for stock engined vehicles at the Indianapolis 500. And as you might imagine, some people were looking at Studebaker’s new President 8. They said, this might be a pretty good idea to look into this as well. Now, this period at the 500, the early, the so called junk formula period, this was very much like open mic night at the Indianapolis 500 for a couple years with all the different manufacturers.

In 1930, you had Buick, Stutz, Oakland, Chrysler, this along with a couple of Maseratis, Mercedes Benz chassis car. Literally, [00:14:00] the quote unquote junk formula where, you know, run what you brung. Looking through the pictures before putting this together, and there’s the picture of the Stutz. And it literally looks like a guy went and got a Stutz Roadster, took the fenders, the splash aprons, running boards off, and painted a number on the side, and he was able to qualify and race.

The Studebaker entries for that year, a quintet of Studebaker engineers got together, said, hey, we can build an Indianapolis 500 race car. They called it the Rompthie Special. That may sound like an odd name. Well, it was the first initial of the last names of the engineers, and they added an E on the end to make it at least pronounceable.

But we see J. C. McDonald, that’s the M in Rompthy, as the driver. And William Richards, the R in the Rompthy, as the riding mechanic. And another name, a privateer, if you will, that was Russell Snowberger in the Russell 8. And he also competed with his, Paul Rice’s riding mechanic, and they qualified for the 1930 Indianapolis 500, one of the many stock blockers there.

And here we see a Russell 8 motor. Studebaker’s present engine was given the usual massaging. You see the magneto down there, four carburetor intake, raised [00:15:00] compression ratio. The standard hot rodding features to get a little more output out of the engine. So how did they do? Well, the Rompton qualified 13th.

It finished 13th. And the Russell 8 qualified 7th and finished 8th, the top finish of the stock block entries. Billy Arnold was actually the winner that year, having the lead from start to finish. But to give you an idea of how the race was going, the first year of the junk formula, In 1929, your slowest, fastest qualifying speed was about 18 miles an hour.

18 miles an hour spread on there. But you’ll see the stock blockers are trying to figure things out as the years go on. So fast forward to 1941, we’ve got the Russell 8 coming back, the Rompsey Special has been renamed the Richards Special because William Richards bought out his partners and set out to campaign again.

And there’s a new entrant, the Hunt Special. This was really a Studebaker, if I could say Skunk Works Project, an off books project. Studebaker was kind of eyeing up the 500, but they weren’t 100 percent sure they wanted to go in and have a grand failure. Looking ahead at what Ford V8s and the Miller component there a few years later, trying to get those cars to work well.

Studebaker wanted to hedge their bets, so they [00:16:00] commissioned George Hunt, their director of testing, to create a Studebaker powered car for the 500. Instead of a home built special, they contracted Herman Ringling from Indianapolis to supply the body and chassis, and then they used the Studebaker President engine.

Which, conveniently, was up to nine main bearings for the 1931 model year. Wouldn’t they have loved to have nine main bearings in 1930? Well, they added that for 1931, and continued to raid the rest of the Studebaker parts bins for the remaining parts. The brakes came from the Studebaker Dictator and Studebaker 6 models.

The rear axle came from a 29 President. And other odds and ends, gauges and whatnot, were sourced from other parts bins. The big news? Russell 8 took the pole in 1931. Now, the Duesenberg and Miller guys didn’t just stay home that year and say, you know, we’re not going to sit there. No, they were there.

Russell 8, with his home built Studebaker President 8 engine, took the pole, finished 5th. Richards, 12th, had some problems. I believe they had a ruptured fuel tank that year and finished 20th. And the Hunt special, steady yet unspectacular, managed to finish 18th. Now Studebaker was satisfied. They were convinced that they could really make a go [00:17:00] of this.

What a go they did for 1932, the company commissioned four additional Studebaker specials. They went back to wriggling and said, we need four more what you built for us in 1931. And again, they were outfitted in the Studebaker shops. This is actually the Studebaker engineering building in South Bend, Indiana.

See, Tony GoTo will hear a little more from him. In a minute right there, as the Studebaker specials took shape. Studebaker advertised these cars as 85 percent stock. This is also Depression Era II. They were trying to say, you know, we’re being sensible with our expenditures, but this is, as Mr. Roos would say, the next year, just an engineering test of our car, for cars that we’re never going to produce for the public anyway, but you get the point, went on Sunday, sell on Monday.

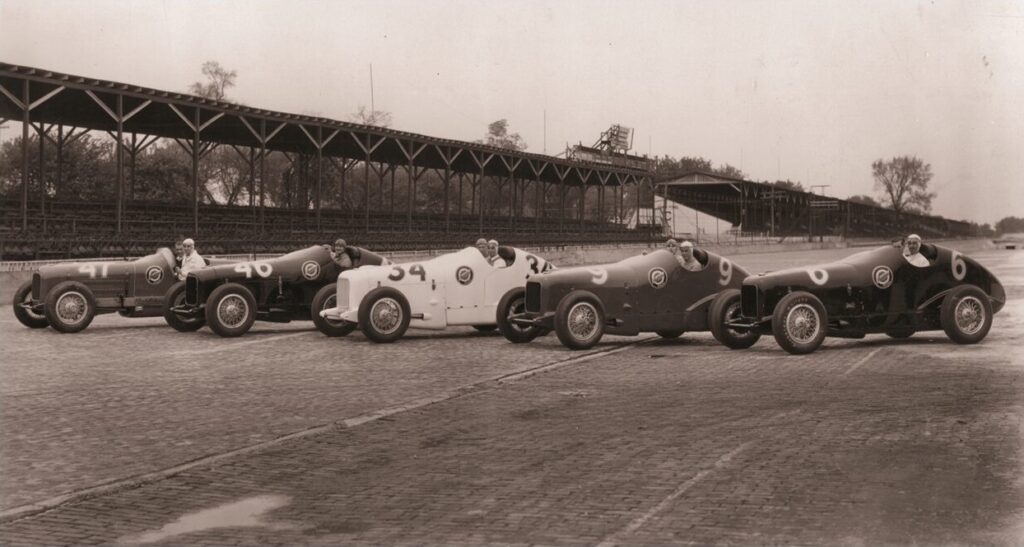

Certainly that was playing into their thinking as well. Here we see the Studebaker team at the 1932 Indianapolis 500. And for drivers, they had quite an impressive roster. Of course, we mentioned Tony Gulotta. We see him right there in the 25 car. Other drivers included Luther Johnson, another Studebaker test driver.

Cliff Berger, who was a Hollywood stuntman and also was an available free [00:18:00] agent. Peter Kreese was a building contractor by trade who also, as I said, he took a month off each year so he could go racing at Indianapolis. As one does, apparently. Most of my friends who are building contractors, they go out on their boat on the lake in northern Wisconsin.

Routing out the quintet was Zeke Meyer, who had experience as an airline mechanic and had been dabbling in racing, I believe he started racing in Indianapolis in 1926. Just from a visual standpoint, you know, you’re from Indiana, home of Studebaker, you buy your ticket to go sit down at the Grandstand, the 500, and you see Studebaker Special, Studebaker Special, Studebaker Special, Studebaker Special, who’s that?

Oh, Duesenberg, and someone else. Number 18 car sitting in the pits here and one of my coworkers was looking at this picture and they said, What’s that? And I said, Well, that looks to be the men’s room. My coworker, Joe McCoy, our assistant director said, Where’s the ladies room? I did not have a good answer for that because I could not find it anywhere.

So at the start of the race, Studebaker drivers were really stressed. It’s important to finish the race. Again, they’re not gonna just pull over and do leisurely drives around the track. There’s definitely competition going on. But they were instructed, try and finish the race. There’s [00:19:00] much more value in that.

So, with a very moderate, aggressive standpoint, and they knew that the Studebakers would hold together, whereas let the other cars break themselves. Ultimately, this strategy proved to be successful. Studebaker did not win the Indianapolis 500 in any of the years they competed, I’m sorry to say. However, they did finish 3rd in 1932, which year started 10th, 3rd, and the other teams shook out.

1315, solid showings and all, and also a rather lucrative year for Studebaker. 1932, they netted 11, 435 in prize money. So for not spending a lot on their specials, was it a profitable event? Is any race unprofitable for the company? But still, I thought that was a fairly impressive return. They could have gotten very little, had things gone poorly for them.

So what do you have in store for 1933? Well, if you aren’t changing something, if someone else will and they’re going to catch you, and Studebaker definitely had it on their minds that they needed to up their game for 1933. What that brought was new streamlined bodies. They used scale models just like these, actually with the aid of the University of Michigan’s wind tunnel, to determine what could be a more aerodynamic shape.

And this is [00:20:00] where you can tell the competitorship is starting to show a little bit with the Studebaker engineers. Even though they said their cars were 85 percent stock and, oh, everything’s the same as last year, they just upped it, no. No, they didn’t. Because we have in Studebaker’s part number list here, 92 in Studebaker language means the 1933 Speedway President.

Notice the name they applied to their grandmother, the Speedway President. In 1931, they had a Speedway package for the President Roadster with a little higher output. Certainly making the most they could on this campaign. These entries, 92 race, these are the race only parts for the 1933 model year. And you come down here, cylinder, part number 180607.

Those were the race only blocks for the 1933 race. They had a few modifications. They also had special heads, special camshafts. And these were only used in the 1933 model year. Indianapolis race cars. This did not cross over to any production model. If anyone sees a Studebaker straight 8 block that has a casting number, please call me day or night.

Feel free to stop by the house. I’ll give you the address. The dog will bark a little bit. Don’t worry about that. He’s friendly. But there are only two of [00:21:00] these blocks known to exist. And we see the new streamlined bodies here on the Studebaker mounts. You notice only four or five cars got the new body.

Studebaker had chosen to sell one of the cars, the 47 car, and it was actually technically owned by Ab Jenkins. Another noted racing driver who had actually done many campaigns for Studebaker, particularly for endurance racing. And he was actually slated to be one of the drivers for the 1932 Indianapolis 500.

Unfortunately, he found closed course driving was not really to his strengths. He much preferred endurance driving, so eventually he relented the driver’s seat to someone else. But as such, because Studebaker did not own the car, they weren’t paying for a free body for Mr. Jenkins, so only the four cars here got the new coachwork.

So how effective was this? Well, the Studebaker bodies and the extra engine components bought them an extra three to five miles an hour of qualifying speed, which was fairly significant. As I mentioned before, the rest of the field was upping their game. Spread from 1931, 16 miles an hour from fastest to slowest.

For 1932, it was six miles an hour. For 1933, it was nine miles an hour. Now, compare this to the last year of [00:22:00] the very exclusive 91 cubic inch formula. That was about a, uh, 18 mile an hour top to bottom speed. So you were seeing a lot more competitive racing from the junk formula, really achieving what they had hoped for.

And this shot, of course, in front of Indy’s iconic Gota. And representation of the Pierce Aero connection here, too. We see in the back one of the Pierce Aero silver Aero show cars. Piercero built these for the 1933 Auto Show Circuit. They only built five. These were actually built in Studebaker’s Experimental Body Shop in South Bend, and, uh, one made it down to the Speedway for publicity purchases at that time.

So, the start of the race again. Studebaker was going through a cautious race, but there were also some additional entrants at the Studebaker Contingent that year. A number of privateers joined the fray. We’ll talk about them in a minute. Pictures you see, I’ve seen many of these, and I always assume the numbers on the grill were just airbrushed in by the photographers after the fact for identification purposes.

It’s like, oh no, they put those on the day of, and he had, here, look at this picture, and it was a picture of the number 34 car, and yeah, it must have been placed on hastily with tape or paint or something like that. They literally painted the number on the front of the car. So here we go for [00:23:00] 1933. This is the Studebaker roster right here.

We see the wriggling chassis cars. You get the Studebaker Special, the factory teams. Russell Snowberger was back with a new chassis, Russell 8. And you had some other, uh, interesting cars in here as well. The Art Rose Special, driven by Dave Evans. That was a front wheel drive automobile. And it was actually powered by Studebaker’s smaller straight eight engine, the 250 cubic inch unit that was used in the 1929 Commander and up through the 1942 President line.

I gotta call out this one here. Yes, this was a Duesenberg chassised race car with a Studebaker engine, which is not something I ever thought I’d say in my life, and I’m gonna say it again. The chassis was Duesenberg, the engine was Studebaker. Doc McKenzie piloted that to an 18th place finish after 192 laps.

And we had three guys who were unable to qualify, Brady and Nardi, Allegheny Metal, and the Snell brothers. And I felt bad for Mr. Speed Gardner, because he has an awesome racing nickname, and he failed to qualify two years in the Studebaker cars. So, I don’t know if he went back to his given name after that or not.

The team best finisher for the Studebaker team was the [00:24:00] number 34 Studebaker Special. It came in 7th. We saw one of the privateers actually came in 6th. And you look at the finish here, we had 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 were all Studebaker powered. From the starting standpoint, just over 20 percent of the Studebaker powered from the factory teams and the privateers.

The bodies were great. There was a minor flaw, however. The streamlining was so good, the cockpits were like Dutch ovens. And the drivers were coming in saying, I can’t go on anymore, it’s too hot. And supposedly, one story circulated that they used a fire axe to actually chop holes into the car to get some ventilation into the cockpit.

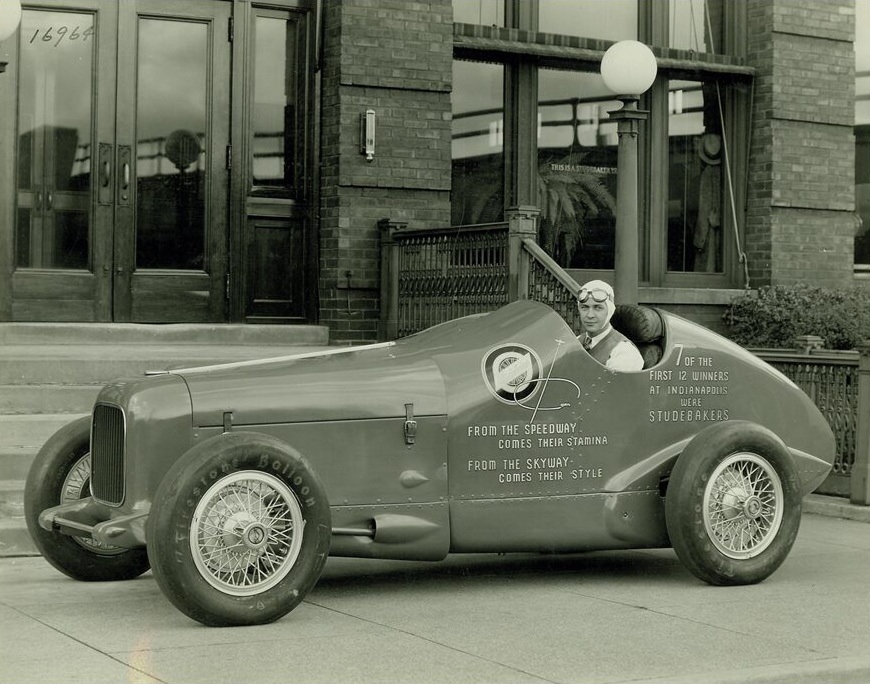

That was not the case. As you can see here, I don’t see any evidence of axe trauma anywhere on the car. And this was rebunked later by some of the other engineers saying, I No, no, we use more conventional methods to keep the drivers cool. Studebaker, of course, wasted no problems advertising their success.

From the Speedway comes the stamina. From the Skyway comes their style. They created this wonderful logo of the circling car on the racetrack and an airplane flying. Seven of the first twelve winners at Indianapolis were Studebakers. How [00:25:00] did you have seven winners at a race? No, you won third place. You won seventh place.

You won twelfth place. It’s all in the copywriting, really. Studebaker promoted that far and wide that their cars had been so successful that Indianapolis and U2 could buy a Studebaker with that racing predigreed engine. Unfortunately, Studebaker had entered receivership in March of 1933. The company was broke, plain and simple.

The only reason they continued at the Indianapolis race was they were able to convince the creditors this is essentially bought and paid for. Whatever our plans were, this will be good publicity that we’re still trying to go on. But when Studebaker entered receivership, that meant the end of the factory backed racing program.

The cars were sold off. Company memo, this was issued on August 28th of 1933. Serial numbers 50 were sold off at 1, 000 a piece. And verified with, these is actually from the 34 car, the engine number and the serial number that correspond with memo. But Sudebaker was still not done racing. They were happy to enter the power plant business.

The smaller Commander 8, used in the Art Rose Special, they were willing to supply those to racers at the mere [00:26:00] cost of 750 a piece. And with that, you got A fully dressed race engine ready to go. See, when I say fully dressed, you’ve got the carburetors. Four carburetor intake, the magnetos. By the way, these are the same magnetos that some Bugatti race cars use.

Which, amazingly, the interchangeability has not brought down their price at all, on the current market. Since we’re back in 34, and it was all privateers from here on out. As I mentioned, the Art Rose Special with his front wheel drive, that’s the Schrader Special for 1934. The Russell 8, again, Russell Snowberger really had the secret sauce for getting performance.

He actually finished far better than any of the Studebaker team drivers. Luke and I were talking about this before. We never figured out why he didn’t hook on a team. Well, maybe he was just making more money being by himself than he was actually under the employ of the Studebaker Corporation.

Studebaker power continued in 1935 and 1936. But by 1935, a new name was starting to appear in the Indianapolis 500 leaderboard, and that was Offenhauser. And you can wonder, what would have happened had Studebaker not entered receivership? Well, I think the, how the racing was going, I don’t know how much longer they could have been a player.

I mean, even without [00:27:00] factory support, they continued to go as long as, we’ll see, 1939. I’m in here, but this is 1937. This is actually the original 22 car from 1933 that had been sold off. It was a Sobonite plastic special in 1937, and the last of the Studebaker cars to campaign at the 500. Another privateer, Joel Thorne Special.

This was Schrader Special we just saw previously. Unfortunately was out of the mix after an accident during qualifying. This car still survives today. Unfortunately still with the damage to the front wheel drive componentry which we found out does not interchange with an L29 cord. So he’s figuring out how to repair that.

The Greenfield Service Special. In 1937, this started life as the American Twist Drill Special. And this was a Perseverance Award. He tried to qualify three, four years in a row, did not make it. Finally was able to punch through and has the distinction of being the last Studebaker powered entry to run at the 500 in 1939, finished 24th.

But not the last attempt at Indianapolis to qualify. The Kiel Osborne Special of 1947. This was put together by two Studebaker engineers. The body was designed [00:28:00] by Virgil Exner, who at that time was in Studebaker styling. And again, went back to the 250 cubic inch President, now the Studebaker President, engine to power the car.

Unfortunately, the car did not qualify, despite two years of attempts. They just did not have enough development time and resources to proceed and make it successful. As for the Sobonite Plastic Special, we just saw Virgil Exner. Bought this car from Studebaker, turned it into a sports car. Virgil Exner Jr.

is still with us and lives in South Bend, Indiana. He remembers going out to meets all across East Side. We were driving an absurd amount of speed on the new Pennsylvania Turnpike with this car. People were amazed that we got from one side of the Turnpike to the other as fast as we could. The SCCA guys did not want to let them in because they said that’s a race car, that’s not a sports car.

Eventually they relented, probably pointing out they’d driven all the way from South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker bought this car back on at least two or three occasions because it appeared at the 1952 Indianapolis 500 when Studebaker paced the event, and we’ll have more on the disposition of that car in a moment.

And here we see Studebaker in 1962, they bought the [00:29:00] 22 car back, as I mentioned, for the second or third time with orders to restore it and also have it functional at its Racing capable speeds from 1932, so they could show off that at the Indianapolis 500. Joining him was the freshly restored 34 Special from the Brooks Stevens Collection.

As Studebaker was showing off their brand new sports model. They did have some difficulty getting the 22 car back together because as strange as this may sound, when they went to rebuild the engine, no one had any bearings for the big President 8. This was the Studebaker factory. They took to sending telegrams to dealers all over the United States.

Does anyone have a set of bearings for a 33 President engine? They eventually found that because the Pierce Arrow Straight 8 was also designed by Barney Roos and is identical in many formats with critical measurements of Studebaker, that engine was used in fire trucks until, I think, right around World War II.

They actually found they were able to adapt some Pierce engine bearings and be able to get the car going again. The Hunt Special, 37 car. And here we get into the nebulous part of what constitutes a car. The running joke with the Studebaker Specials is, of the five were built, eight remain. We’ll get to that in a minute here.

The Hunt Special, [00:30:00] 37 car. This is currently out at the Price Museum of Speed in Salt Lake City, Utah. Number 34, Studebaker special. It, too, suffered the indignity of a roadster body applied to it. The original body sat outside a garage in Chicago for many years. It was actually advertised, I believe it was in Car Classics magazine.

And the 34 car was acquired by Brooks Stevens in the late 1950s. It was sitting on a used car lot in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Brooks knew what they had, so he got it and commissioned a restoration. He actually had the back section of the body rebuilt from scratch, just from photographs. And they were nearly done, and someone calls and says, Hey, we have the original body.

Do you want it? How much? I heard that I think it was 25. Nope. Don’t want it. Don’t need it. That body is actually out in California as part of another Studebaker Tribute Racer. Or is it not a Tribute Racer because it has part of the original body? That’s a debate for another time. The 22 car is down at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, currently on loan to us at Studebaker National Museum.

Now here’s where it gets a little foggy. The 18 car, still with us, you see it right here, this is actually out from the [00:31:00] vintage races in California. The body, grill, and some aftermarket frame rails were found in a garage in Chicago. The story is, it was the most crowded garage you ever saw, but there was the Studebaker body.

Collector Mike Cleary from California acquired the body with aid of a Studebaker President Parts car and a lot of fabrication skills. Mike is a very skilled engineer. They were able to create the new No. 18 car. As for the original chassis of No. 18, that car went down to South Africa. And it was actually raced up into the 1950s, at which point it was disassembled, broken down, and used for spares.

The story I heard was the engine was actually used to power a Studebaker President Hearst from the early 1920s after that. And we have boots on the ground in South Africa. They’re still trying to track down any remnants of this car, but I’m afraid that one is lost to the mists of time. And lastly, the Kill Osborne Special, it was sat in a garage in South Bend, Indiana for a number of years until the guys who had it said, you know, this isn’t really practical as a race car.

We’re going to make a home built roadster out of it using 1950 ish Studebaker parts. The car still survives [00:32:00] today. No one really knows where it is. We suspect it might be in the South Bend area, but we’ll save that for talk some other time. And with that, I will be happy to field any questions. That logo that was from the Skyway comes the style?

From the Speedway comes their stamina, from the Skyway comes their style. Is that a Chicago Skyway bridge reference? No, it was referring to aviation, just the byways and skyways of America. Oh, so it’s an aviation reference. Yeah, because they actually had the little, uh, airplane going up. And that was really, Studebaker was hung up on the whole Skyway moniker.

In fact, they introduced a trim level in 1941, the Skyway series of cars. They really, uh, Really? We’re pushing that hard. Oh, very good. Thank you. The mantra for a long time, since the thirties actually was went on Sunday, sell on Monday, did Studebaker get in to racing in order to help sell production cars and if so, and, and obviously they were in it for a fair length of time, but they went into receivership.

So. It didn’t really seem to help, but it was a very ambitious effort. I’m just wondering if it correlated to trying to sell production cars. I feel bad that I didn’t include [00:33:00] graphs in here, because it would actually be very depressing. Did the success in 1932 with the third place finish help the president model for 1933?

Nope. 33 was the worst sales year and the depression had a lot to do with that, trying to sell their luxury model. Did it help them buy time with the receivership to show their viability? You can’t really measure that, but the fact that there was interest, there was helpability. The sales were one part of it.

Studebaker President Albert Erskine also, his business practices had a lot to do with receivership. You know what happens to your capital reserves when you pay out a dividend and yours you don’t show profit? They go away very quickly. In 1932 or 33, he paid out 506 percent of net profits in dividends.

And that’s what happens when you pay out dividends when you show a loss. He was convinced prosperity was just around the corner. It’s not. And Studebaker suffered the consequences. And it’s really, Studebaker could have folded up the tent in 1933. That could have happened very easily, but they managed to convince the bankruptcy judge that their best course of action to satisfying their creditors was And they hung on for another 20, 30 years.

Do you know what the [00:34:00] last race car to be powered by a Studebaker was? We’ll have to define your terms a little bit here, but go ahead. Okay, in 1965, the Canadian Grand Prix, for the most part, David Hobbs drove a Lola T70 powered by a Studebaker. He qualified second. It was entered by, uh, Harold Young Racing, I believe, the Canadian team.

I did not know that. Mr. Hobbs was just down at the Chattanooga Concours. I wish I could have discussed that with you. No, no. So you went through years rapidly there. Which year did they take the pole? 1931. Alright, 31. Then was it the following year they had multiple cars, but nothing more than 7th or 8th position?

In 31, Russell Snowberger took the pole. He was a privateer. He did not work for Studebaker, but it was the Russell 8 with the present engine. The team in 32, they had their best finish 3rd, the number 22 car, I believe. Cliff Ger was behind the wheel of that car and in 33 they were moving a little back in the qualifying, but they also, they hung in 33 was one of the most traumatic races the Speedway ever saw, just with the carnage.

And I wanna say there was [00:35:00] only 14 or 16 cars running at the end of the race, but all the Studebaker team was able to finish race. They never really had any terrible mechanical difficulties. But yeah, when that’s, when they say seven places, actually six through 12 in 1933 were all Studebaker power. So why the drop off?

Because of the carnage of the race? I mean, they Well, I mean, racing If I remember the qualifying speeds or whatever, they seem to suddenly drop down. The qualifying, they actually picked up a couple miles an hour qualifying from 30 to 33 with the new bodies and the new engines. But relative to the competition?

Relative to the competition, yeah. You started to see some of the more specialized You know, the Miller Duesenberg engine cars of that ilk were starting to spread the gap. And, like I said, when the Offenhauser came online in 35, you could really see the handwriting on the wall for the stock locks. That was fascinating.

Thanks, Hender. Appreciate it. Yes, they did race at Indy, Kip. Yes, they did, I guess. This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and [00:36:00] preserve the history of motorsports, spanning continents, eras, and race series. The center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives.

org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.[00:37:00]

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of Fig Newtons, Gumby Bears, and Monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT Motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be [00:38:00] possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Studebaker’s Early Motorsports Involvement

- 01:27 Andrew Beckman’s Background

- 02:51 Studebaker’s Racing Philosophy

- 04:32 Studebaker’s Early Racing History

- 09:50 The President 8 and Racing Innovations

- 13:19 Studebaker at the Indianapolis 500

- 17:00 The 1932 and 1933 Racing Campaigns

- 20:50 The Elusive Studebaker Straight 8 Block

- 21:01 Studebaker’s Racing Legacy

- 22:29 The 1933 Indianapolis 500

- 23:14 Privateers and Unique Entries

- 25:14 Studebaker’s Financial Struggles

- 25:30 The End of Factory-Backed Racing

- 26:16 Studebaker’s Continued Influence

- 27:03 The Last of the Studebaker Racers

- 28:55 Restoration and Legacy

- 32:05 Q&A Session

- 35:54 Sponsors and Closing Remarks

Livestream

Bonus Content

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

Learn More

Visiting the Studebaker National Museum

The Studebaker National Museum is housed in a state-of-the-art, 55,000-square-foot facility that opened in October 2005. The building has three levels and features fully climate-controlled galleries and storage facilities to ensure the best possible care for the Collection. The Studebaker National Museum was designed by South Bend’s own James Childs Architects and features several design elements from Studebaker’s factory buildings.

Studebaker’s official team debuted in 1932 with four factory-backed specials, built in collaboration with Indianapolis chassis maker Herman Ringling. Drivers included Tony Gulotta, Zeke Meyer, and Cliff Berger – a Hollywood stuntman moonlighting as a racer. The team’s cautious strategy paid off: Studebaker finished 3rd, 13th, and 15th, earning over $11,000 in prize money during the depths of the Great Depression.

In 1933, Studebaker upped the ante with wind tunnel-tested streamlined bodies and race-only engine blocks. These “Speedway Presidents” gained 3–5 mph in qualifying speed, a significant edge in a tightening field. Though they didn’t win, Studebaker-powered cars filled positions 6 through 12 – an impressive showing for a company that claimed it wasn’t trying to win.

Studebaker’s Indy adventure ended as quickly as it began, but its impact lingers. From pace car replicas to race-only engine blocks (only two known to exist), the company’s brief flirtation with motorsports left behind a trail of engineering innovation and marketing savvy.

As Andrew Beckman, archivist at the Studebaker National Museum, quipped during his presentation: “If anyone believes that anyone entering a race is not trying to win… well, I wouldn’t lend them any money.”

Studebaker may not have claimed the Borg-Warner Trophy, but for a few thrilling years, they proved that even a company known for cast iron and caution could chase glory at the Speedway.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)