In the early 1960s, Ford found itself struggling to appeal to younger buyers, losing market share to General Motors. To reverse this trend, Lee Iacocca spearheaded the “Total Performance” program, using motorsports as a marketing tool. This included efforts in drag racing, NASCAR, IndyCar, and international road racing. However, there was one glaring gap – Ford lacked a car capable of winning outright at Le Mans.

Meanwhile, Enzo Ferrari, concerned about his company’s financial future, entertained discussions of selling Ferrari to Ford. The negotiations, however, fell apart at the last moment, enraging Henry Ford II. His response was decisive: Ford would build a car to beat Ferrari at Le Mans.

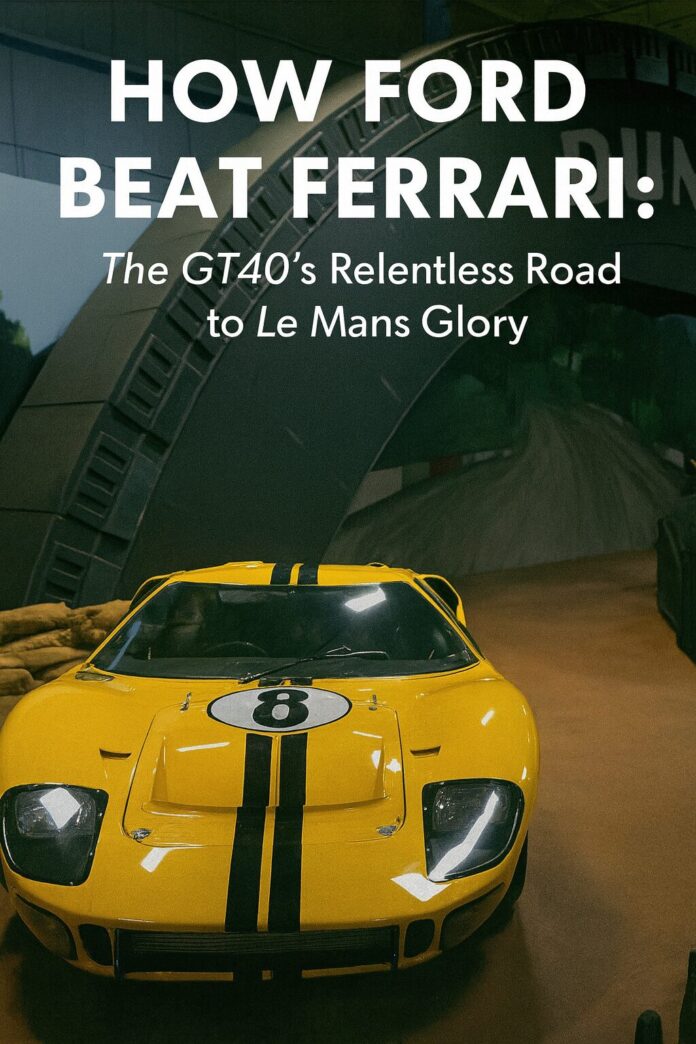

Engineering the GT40

Ford’s engineers lacked experience in developing a mid-engine prototype race car. To solve this, they enlisted British expertise—specifically Eric Broadley of Lola Cars, whose Lola Mk6 GT already fit Ford’s vision. This partnership led to the creation of Ford Advanced Vehicles (FAV) near Heathrow Airport.

Despite initial promise, the GT40 faced numerous technical hurdles. Early aerodynamic instability made the car nearly undrivable at high speeds, leading to disastrous test runs and race debuts. Adjustments—including a rear spoiler—stabilized the platform, setting the foundation for continued development.

The Shelby Era

Following a lackluster 1964 season, Ford handed the GT40 project to Carroll Shelby’s team. Based in Southern California, Shelby American had access to a deep talent pool and cutting-edge aerospace technologies. Shelby’s team replaced the GT40’s underwhelming Indy-derived 255-cubic-inch engine with the proven 289 small-block V8, improving reliability. Their relentless testing at Riverside and Willow Springs paid off—Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby secured the GT40’s first victory at the 1965 Daytona 24 Hours.

Yet the 1965 season overall was far from successful. Ferrari still had the upper hand, and Ford’s GT40s suffered from fragility. This led to further enhancements, culminating in the GT40 MkII—fitted with the monstrous 427-cubic-inch big-block V8 from NASCAR.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

The Legendary 1966 Le Mans Victory

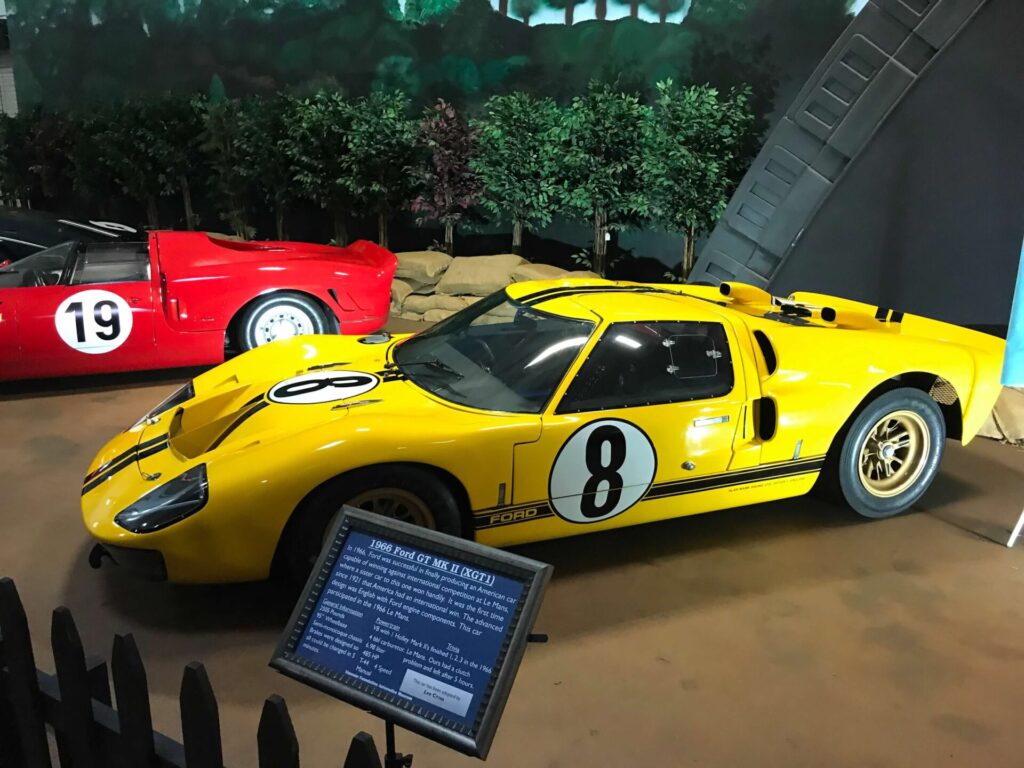

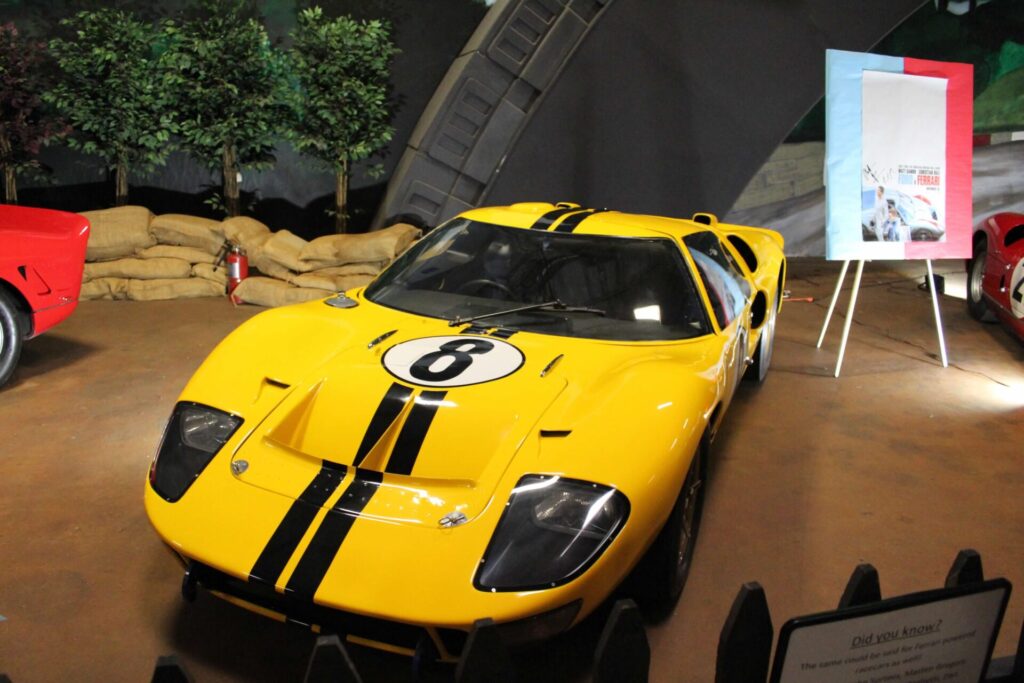

By 1966, Ford arrived at Le Mans with an unprecedented effort: eight GT40 MkIIs fielded by Shelby American, Holman & Moody, and Alan Mann Racing. Ford mandated conservative lap times to ensure reliability, yet the race still saw fierce competition between the leading GT40s. Ken Miles, driving one of Shelby’s MkIIs, dominated much of the race.

A decision to stage a dead heat finish—where two Fords would cross together—led to controversy. Due to a technicality in the race regulations, Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon’s car was declared the winner over Miles and Denny Hulme’s. While Miles had seemingly secured Ford’s victory, he was denied the official win. Nonetheless, Ford’s 1-2-3 finish cemented its dominance over Ferrari.

1967: The Pinnacle of American Motorsport Engineering

Following their triumph in 1966, Ford introduced the GT40 MkIV, incorporating aerospace-grade aluminum honeycomb chassis construction and radical aerodynamic refinements. Developed through extensive wind tunnel testing, the MkIV was designed for speed and stability.

Dan Gurney and AJ Foyt piloted the MkIV to victory in the 1967 Le Mans race, dominating Ferrari and Chaparral’s latest challengers. Gurney’s innovative use of throttle control reduced brake wear, ensuring the car’s reliability. This victory—an all-American effort featuring an American car, engine, and drivers—marked the ultimate success of the Ford GT program.

Spotlight

Few cars capture the essence of American performance and racing heritage quite like the Ford GT. In his book Ford GT: How Ford Silenced the Critics, Humbled Ferrari, and Conquered Le Mans, author Preston Lerner takes readers on a thrilling deep dive into the history, engineering, and racing legacy of this iconic machine. From the groundbreaking GT40 that stunned the motorsport world in the 1960s to the modern GT’s triumphant return to Le Mans in 2016, Preston masterfully weaves together the stories of the visionaries, drivers, and engineers who made it all possible. In this episode, Preston explores the book’s most fascinating insights, discuss Ford’s relentless pursuit of victory, and uncover what makes the GT one of the most legendary race cars of all time.

Preston Lerner is a freelance writer who has covered racing for the past four decades. For many years, he was a regular contributor to Automobile Magazine and Road & Track. Lerner is also the author or co-author of six books, most recently Shelby American: The Renegades Who Built the Cars, Won the Races, and Lived the Legend. The material used in “Television Turns Its Gaze on Motorsports” is drawn from his upcoming book, The Deadliest Decade, which examines the safety, commercial and technological developments that transformed racing from 1964 to 1973.

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer family.

Crew Chief Eric: Few cars have captured the essence of American performance and racing heritage, quite like the four gt.

In his book for GT, how Ford Silenced the Critics Humbled Ferrari and conquered LeMans author Preston Lerner takes readers on a thrilling deep dive into history, engineering, and racing legacy of this iconic machine from the groundbreaking GT 40 that stunned the motorsports world in the 1960s to the modern GT’s triumphant return to LAMA in 2016.

Preston masterfully weaves together the stories of the visionaries, drivers and engineers who made it all possible. In this episode, we return to the International Motor Racing Research Center for a center conversation where Preston explores the book’s most fascinating insights [00:01:00] discusses Ford’s relentless pursuit of victory and uncovers what makes the GT one of the most legendary race cars of all time.

Tom Weidemann: For those of you who have not had a chance to meet, my name is Tom Leman. This is one of the most delightful opportunities I get to welcome people to our center conversation, and particularly today with our wonderful speaker Preston, learn Pressure. Pressure present. I am delighted to have such a wonderful crowd here today to hear this presentation, and let’s get right to it.

Ladies, let introduce Preston Lerner and his talk on. Let’s see, where is that? Oh, it’s the GT 40. Are you ready Preston? I

Preston Lerner: think Don’s going first.

Tom Weidemann: Sorry about that. Don. Don Caps is a member of our historians council, a great friend of the center. And so now let me bring up Don Caps, we’ll get you more information.

Done

Don Capps: sheet, the center time stations, which have been going on since what, 2000 late [00:02:00] 1999, 2000. Uh, I’ve been here as with this time, they have someone like Preston and some of people will come. This is great. Plus this is a wonderful crowd. Today, Preston and I have gone back a little ways back and forth on some.

Preston is a contributing writer for a automobile magazine and is, uh, written several really interesting books. Scab, which is still kind of a milestone for that particular mark, still into Paul Newman, uh, Mexico. Also really wonderful book on automotive mythology, which, uh, I, I’ve enjoyed that one a great deal because it, it made a very dear lady, very happy to see something that she had a research on.

You have to read a book, but one is very dear and dear to all of us who are here today is his work on the 4G two and race of 1966. I know how many of you remember back in the, uh, the dark ages where about two or three times a year you [00:03:00] get a satellite TV beamed in from France on the Obama race, and there it was, the American cars coming across the line in.

And that was an incredible experience to see it live all in any color you want, along to black and white. So things have changed a great deal and one of the things that’s nice to have someone like Preston here is he brings a tremendous of amount of information and knowledge on the automobile world.

All so basic. Somebody really doesn’t need an introduction, but someone who really, uh, I.

Preston Lerner: Thank you, Don. Thanks also to Tom and Glenda and Josh and Bill and Kip and everybody else here at the International Motor Racing Research Center. This is my first visit. It’s a fantastic facility and it’s an honor and a thrill [00:04:00] to stand at the spiritual home of American Road Racing. I am the author of four gt and if you can see from this unconscionably long subtitle, my book is specifically about the Forge Factory program to win La Ma.

Ford advanced vehicles built 133 or a hundred thirty four four GT forties. Only about two dozen of them were raced by the factory. The rest were sold to private tier. Some of them had some amazing successes. The most famous, and a lot of you here probably know it was chassis 10 75, which went on to win Lama two years running in 68 and 69, and they were four GT forties that continued to race and club races well until the seventies.

So there’s a lot of history there, but I’m really focused very specifically on the year 63 to 67 when Ford ran a factory program. You know, a lot of stories have been told about the GT 40. Several excellent books have been written over the years and there are still some points of dispute. You know, I reached my own conclusions.

Your mileage may vary, but this is the story as I see it. At any rate, and I’m happy to, to answer as many questions as you guys have. I. The Ford GT Saga begins in the early [00:05:00] 1960s. Ford’s products have become very stodgy and the company was losing youth sales and market share to General Motors. So at the tail end of 61, Lee Iaccoca was brought in to run Ford Division, and one of his primary objectives was to appeal to the first cohort of what we now call the baby boom generation.

One of the ways he wanted to do that was to implement the win on Sunday, sell on Monday concept. Ia. Coco was instrumental in inaugurating the Total Performance Program, and the idea was to use racing as a marketing tool to appeal especially to younger buyers. So total performance ended up, there was a whole bunch of stuff that they did, but the four major components, at least for our purposes, they did drag racing, which was based on the muscle cars that were already coming off the assembly line.

They did stock cars with Holman and Moody, and they. They sent a whole bunch of money down to Charlotte and Motors, especially the 4 27 big block they did in cars. Winning Indy was their big goal. Created a special motor, 255 cubic inch twin cam, forward 4K motor, which became one of the great [00:06:00] engines in, in, uh, indie history.

And there was road racing, uh, with the cobras, which were really successful here in the states. And would go on to be very successful overseas. But you know, the Cobra was a GT car and it wasn’t really eligible. It was never gonna win LAMA overall. And frankly, no one in the United States or very few people in the United States knew anything except for Lama and Ford had nothing in its inventory to go win Lama.

So at the same time that these things are going on, uh, here in the states, Enzo Ferrari in Marine, he was looking to the future and was, and was worried about what was gonna happen. Ferrari was, in certain respect, the polar opposite of Ford because Ford used racing to sell streetcar. Enzo sold street cars to fund racing.

And he could only sell so many cars because there was, you know, a relatively small market for it. And he was wondering how long he was gonna be able to fund the racing program to continue to win at endurance racing at Lamont. And he was also in Formula One in a big way. So Ferrari let it be known through his emissaries that he might be willing to sell the company.

Ford got wind of this. They sent over a bunch of accountants and technicians. They inventoried the factory. They looked at the books they sent over Don Fry, [00:07:00] which who was uh, Lee Coco’s, right hand man to negotiate directly with Enzo Ferrari. And torturous negotiations ensued. They hammered out a purchase price, actually put together a contract, and at the 11th hour, Enzo got cold feet and he left Don Fry standing at the altar.

Conspiracy theorists are convinced that Ferrari never intended to sell to Ford, and that this whole ploy was a charade to convince Fiat to buy the company. And in fact, Fiat did buy the company a couple years later as devious as Enzo Ferrari was. I think that’s a little more Machiavellian than he truly was.

You know, my reading of the subject is that the more the negotiations went on to be clearer, he came to Ferrari. But if he became part of the Ford Corporate Empire, he was no longer gonna be able to act like an absolute monarch, which is what he’s been since he started the company. So he told Don Fra, he wasn’t interested.

Ferri goes back to Dearborn. He meets with Henry Ford the second. Henry known as the Deuce, was the grandson of Henry Ford. He, he was the CEO and president of Ford Motor Company. He’d been running it since World War ii, and he was every bit as autocratic as Enzo Ferrari. And so when [00:08:00] Fry tells Henry what happened, Ford was convinced that Enzo had essentially given him the middle finger.

So he told Fry, well, that’s the way he wants it. You go over there and whip his ass. Or he may have said, you go to Lamont and beat his ass. It’s actually not clear exactly what he said because Fry told the story different ways to different people. The salient point is that Henry Ford wanted Ford Motor Company to win Lamont and he wanted to humiliate Ferrari in the process.

So that’s what they set out to do. But the problem was Ford didn’t actually have anybody in its entire company, which was something like 350,000 employees who knew anything about international road racing. And the only guy who sort of knowledgeable on the subject at all was a British transplant by the name of Roy L.

And L had run the Aston Martin program that went to Lamont in 49. That actually sounds a little more impressive than it is because back then the Astons were essentially modified street cars, and after that L had nothing to do with racing. He worked on the production side of the business for Owt and then for Ford of England.

Then he came over to the States and he worked in RD at Ford. But in the land of the blind, the one eye [00:09:00] band is King Roy Lund was tasked with putting together a proposal that would be presented to the Ford management to sort of green light this program. Lum was a, was a clever guy, a clever engineer, and he realized that what Ford needed, uh, was gonna be a, uh, a mid engine MoCo with a swoopy aerodynamic body powered by a Ford V eight.

He also roughed out the dimensions of the car, which he called the GT 40 because it was supposed to be 40 inches high. He. So L and Don Fry go to Ford Management. They present this plan. Ford Management says, great, go in Lama. They didn’t think it was really gonna be that big a deal. You know, L was the one who really understood the enormity of the, the project that Ford had ahead of it.

So the problem was there was nobody at Ford who knew how to build a car like this. And in fact, there was no one in the United States who really had any experience with mid-engine Monaco chassis. So Roy Lund decided to go to England to find somebody to design and build the car that would go to Lamont.

And they considered a couple of possibilities before deciding on Eric, broadly. Broadly, had been working in the construction trades in the mid fifties when he built a special to go road racing the club level [00:10:00] himself. And his car was so successful against the Lotus’s that other guys commissioned cars from him.

And eventually he was successful enough that he created a company called Lola Cars. And in 63 he had wowed the motorsports world with a car called the Lola Mark vi, or sometimes Lola gt. And this was a mid-engine Monaco with swoopy aerodynamic body work powered by a Ford V eight engine, which is to say it was exactly what Roy one was looking for.

Broadly is hired the company lease a shop space near Heathrow Airport. Forms a company called Ford Advanced Vehicles. To build the cars broadly brings his small Lola crew over John Wire, who, uh, had become famous for Ram rotting. The Aston Martin team that won Lamont 59 was brought in to run the operations.

So to keep the trains running on time, John Wire was nicknamed Death Ray, you can sort of get the sense Y from the way he looks here. He wasn’t a good guy to have mad at you. And then Roy L came over to England with three Ford engineers and they went to work. Now one of the pervasive myths that really kind of annoy me is that people [00:11:00] say that the four GT was nothing more than a warmed over Lola, and that’s demonstrably false denied explicitly by broadly and wire and L.

The engine was entirely an American product, obviously. It was the, it was essentially the 2 55 cubic inch Indy car motor with a push rod valve train instead of a twin camera arrangement. The body, which you saw before actually had been a full-size clay had been done before Braley was hired. Lauren had already sketched out the dimensions before Braley was hired.

The Monaco had a lot of Lola stuff in it, no question about it. But it was bigger and more robust. And frankly, the Brits were aghast at how heavy it was. The suspension was pretty much standard race car practice of the day. But the suspension geometry was put together by a Ford engineer back in Dearborn who was using software written in Fortran on an IBM mainframe.

Not sure how that, well that worked. So it was really an an Anglo-American collaboration in the truest sense of the word, and I think that’s the best way to think of it. The collaboration didn’t go all that smoothly to be honest. There was a serious culture clash, and it wasn’t so much between Americans and the English, but it was [00:12:00] the Ford guys were formerly trained engineers who were used to working in a corporate environment.

You know, they were accustomed to protocols and design reviews and all sorts of formalized procedures to follow, and the Brits were racers. It wasn’t that they, you know, were shade tree mechanics, but they were used to doing things on the fly and making corrections as necessary. The two groups did not get along at all.

The Americans thought the Brits were kind of bumpkins, and the Brits thought the Americans were sticking the mud. So before too long, Roy Lun and Eric Broley, who were the two people in charge of the program, weren’t even talking to each other and everything had to go through Roy Lu and that didn’t work too well.

Originally, they had hoped to race the beginning of the 64 season, and in fact the first car wasn’t finished until April 64 and it was shown briefly here at Heathrow Airport, and that’s actually wire on the left, broadly in the middle, and a rare picture of Roy L on the right. And then it was flown over to the States where it was shown very briefly to the American media.

Uh, right before the New York Auto Show and then this car, which is the first car, was sent over to La Ma for the Lamont test, and there was a second car finished so late that it was shipped over to France without even [00:13:00] being graphic up properly. So needless to say, the cars hadn’t been tested really at all.

They’d just been shaken down to make sure they would run. They get to La Ma and it’s a disaster. These are cars that are supposed to go 200 miles an hour. And at 150 miles an hour, they were all over the road. Joe Lescher, French driver, who was brought in because Bruce McLaren wasn’t available, goes out in the first car and immediately totals it.

Uh, the bulls on kink. The second car is driven by Roy Salvadori, who had won Lamar with Carol Shell being 59, and he’s cajoled by a wire to get back into the car on the second day, and he does so against his better judgment and proceeds to crash the car at bulls on hairpin, cranks the front end. And so that car’s done for the day.

Salvadori was so unimpressed by the car that he immediately quit the program in the interest of his self-preservation as he put it. In fact though, that was, that was the wrong call on Salvador’s part. The problem with the car was that the aerodynamics of the body work produced a bunch of rear end lift, which is exactly what you don’t want in a race car.

I. Simply by slapping a spoiler on the rear deck that settled down the rear end and thereafter, pretty much everybody who drove the [00:14:00] Ford GT said it was among their favorite cars ever. It was a big car. It was a heavy car. It was not good and then slow stuff. It wasn’t agile, but it was extremely stable and benign and medium speed and high speed corners.

It was faster than any indie car or uh, formula one car in a straight line. Ford had spent a lot of time on the cockpit making it comfortable, which was very unusual in those days. You know, Ferrari didn’t care about his drivers. So it was, it was really good for long distance races and, and it had the, the one quality that drivers want most in a race car, and that is that it was fast, it could win races.

And so drivers generally love the GT 40, the guys who drove it except for Roy Salvador, of course. So month after the two cars are wrecked at lama, there’s a car, I believe this is, the second car was repaired and it goes to the Burg Green for its race debut. Berg Green really was the wrong spot for debut, but it was the only chance to race the car before Lama.

So that’s where Ford decided to go. Phil Hill and and McLaren are in the car. They qualify second to John Ciz and the lead Ferrari. They run second in the race, but then they break predictably pretty early on for Lama. Then it’s a month later. So they had three cars of Lamont, which is pretty impressive for a brand new operation.

End of the first [00:15:00] lap, Ferrari are leading. 1, 2, 3. They go down to Church Rouge, which is, you know, is the right hand or leads onto the moles on Strait to start lap two. Ferrari is 1, 2, 3. The fourth car in line is Richie Ginther and he’s behind them and at the end of the moles on straight, he is passed all three Ferrari and he is disappearing into the distance.

Ginther leads easily for the first hour. He pits Maton. Gregory gets in the car. Maton Gregory leads easily during his stint. The car is the fastest car on the track, but unfortunately it breaks. Second car catches on fire, so its race is over. Third car is Bill Hill and Bruce McLaren, and they’re delayed at the start.

They have a misfire that takes ’em a while to figure out, but once the car’s going, it’s also the fastest car on the track. Sets the track record, but then it fails slightly before a half distance. All three cars failed, which is not what you want when you go racing, but reliability is something that you can deal with.

At least the cars were fast. That’s what you want with a new car. You want it to be fast. You can always work on fragility later on. Generally speaking, the Ford Camp was upbeat after that first Lama. The rest of the year didn’t go quite as well. They raced at, ran in France shortly after Lamar, and the cars performed very [00:16:00] badly.

So thereafter Wire decided not to do any more racing and he wanted to focus on testing and development. But towards the end of the year, he was told he was ordered actually to prep two cars for. The Nassau speed weeks and he didn’t want to go there. There was racists in The Bahamas. They were kind of a, they were a run what you brung deal.

They were, it was on a tight circuit. He thought it was a waste of time to go, but he was, as I say, uh, coerced into, into sending two cars there. And the problem is, is they, uh, they do terribly here. They’re being outrun by a cobra of all things He. Both of the four GTS break and they’re beaten by GM products, which sort of adds insult to injury after Nassau.

There’s a big powwow back in Dearborn and the Ford discusses what went wrong with the season and they decided that the problem with the four GT program was not the cars, it was John Wire. So they fired John Wire, although they let him continue to run the customer racing program, and they decided to have the racing program run by their in-house snake charmer, Carol Shelton.

Don’t think Shelby needs much of an introduction here. One of the most charismatic figures ever. Great driver, he created the cobras. What’s important is he’d also put together a race team called [00:17:00] Shelby American based in Southern California. And I know today it sounds weird to think of a racing team in, you know, in Los Angeles because you know, everybody’s in Charlotte or they’re in, uh, Indianapolis or somewhere near a racetrack.

But Southern California had been the home, the really center of, uh, American racing industry pretty much since Harry Miller, uh, opened his shop in downtown Los Angeles in the teens and well into the fifties. Most of the, the really competitive Indy Roadsters and sprint cars and midgets were still coming outta shops in Los Angeles.

I. In addition to all the, the sort of racing history, Southern California was the birthplace of hot rod civilization, so there was a tremendous talent pool of really good craftsmen, experienced race mechanics there for Shelby to choose from. And Southern California was also where all the aerospace stuff was happening in addition to the people.

Shelby had access to a bunch of materials and components and technologies that were just then finding their way in into the motorsports world. I mean, stuff like titanium and fittings and stuff, we really all take for granted now. I mean, that was just then moving over into that world. So Shelby put together a really impressive organization.

I don’t have time [00:18:00] unfortunately to, to talk about all the people who went on to bigger and better things, but two of them deserve special mention. First, Phil Remington, master of all trades. Remington could do pretty much anything. He was a machinist, he was weld, he could fabricate, he could tune, suspensions, breathe on motors.

I mean, he could do it all. The thing about him that made him difficult to work with was not that he was difficult personally, he was actually a very pleasant guy and and extremely humble considering how accomplished he was. But as I said about him, he could do everything that, that you could do, and he could do it faster, and he could do it for longer than you could do it.

But Carol Smith, who was the race engineer, you guys have probably seen his tune to Win and Fasteners to win all his books. He said that Remington’s greatest skill was that he was a problem solver and he would come up with fixes before other people even realized that there was a problem. So Remington’s number one, and I think he was probably the single most important person in the four GT program.

Second was Ken Miles. I was a Brit. He’d driven a tank after D-Day in World War ii, come over the California in the fifties to work at an MG dealership. Was a champion, small boar racer in West Coast racing. Was [00:19:00] hired by Shelby for the COBRA program. Won a whole bunch of races in Cobras. Besides being a really talented race car driver, he was a test driver at Parx launch and he could drive for hours on end at nine-tenths without damaging the car, and then come back and tell people exactly what the car was doing in the middle of turn six, you know, at 4,200 RRP M or whatever it was.

So he was an invaluable resource. The cars come over from England in December of 1964. And they’re immediately Shelby eyes. First thing they do is they paint ’em. Blue is a Shelby Blue. Next thing they did, these are the bari wheels, uh, wire wheels were replaced by, uh, good old American Hali brand mags. The 2 55 IndyCar motor is replaced by a 2 89 small block, which had been proven in the cobras already.

They started testing the things mostly at Riverside. This happens to be at Willow Springs, which is north of la. Miles and Bonderant would bomb around the track for hours on end. They’d report all their issues to Remington. Remington would make the fixes implement them. They’d go back out to Riverside in rural springs and repeat as necessary.

They only had about six weeks for Daytona, but they sent two [00:20:00] cars to Daytona and lo and behold, miles and Lloyd Ruby win in their first doubting for Shelby American. So as you can imagine, the uh, four guys thought that Shelby walked on water after that. It was not only the first win for the four GT, it was the first time the card ever come close to finishing a race.

Unfortunately, I think the British expression is that it flattered to deceive because this turned out to be the high point of the 65 season. The rest of the year went pretty disastrously. They were beaten everywhere and they were humiliated a couple places. Ford realized it needed to sort of do something to raise its game, so to speak.

So one of the steps they took was to create an in-house subsidiary called CarCraft, and this was a quasi works skunk works. Where Ford engineers were sent either on the payroll or to moonlight and come up with the r and d, uh, improvements to advance the program. And one of the things they decided to do was to use the 4 27 cubic inch motor, the big block, which was being raced really successfully in NASCAR by Holman and Moody.

And so the guys at Car Craft thought it might be a good idea to see if they could stick a 4 27 into four gt. [00:21:00] And it really wasn’t a particularly difficult conversion. They had to cut a rear bulkhead, they had to move the seats, a bunch of plumbing changes. Later on, they developed a new transmission, but by and large, it was a pretty simple conversion by industry standards.

And when they finished the car, Ken Miles was dispatched to Michigan to the Romeo test track to see what the car would do. And after shaking it down, he goes out and he pretty immediately gets the car up to 200, 1.5 miles an hour. And he, when he gets out of the car, Roy Luon says to him, what do you think?

And Miles says, that’s the car I wanna race at Lamont. Which is good, except that there was only about six weeks to go before Lamar. There’s now, now a rush program to get the car prepared. The new car, the big block car, is dubbed the Mark two and the small block cars are retroactively named Mark ones just for future reference.

So for Lamar Ford shows up with six cars. They got two mark twos, brand new four mark ones. The Mark twos had barely been shaken down before the race, and when they got to the track they found out they were wicked loose. And that’s really a problem in La Ma, which was one of the fastest tracks in the [00:22:00] world.

So during the course of practice and qualifying, the Shelby American guys spent most of their time behind the pits, cutting aluminum, shaping it, and then, uh, fixing it. These appendages to the race corner. The car is completely clean. Aerodynamically when it showed up. Lamont here, it’s got a front air dam.

It’s got a canards on the, uh, front fender. It’s got these weird looking tail fans on the rear deck, and it’s also got a big rear spoiler, which you can’t see. So the car looked kinda like a frankensteinish, ran like a monster out on the track. And as soon as the race starts, puts Bruce McLaren in the lead, Chris Amen.

Behind him. When they get to the end of the MOS on straight at Lap one, they can barely see the Ferraris and near view view mirrors. These guys dominate the race and the mark twos until they break. This is kind of a common theme with the Ford story. It turns out the problems were really kind of fluky deals that didn’t have anything to do with the new motor, but nevertheless, the car is broke and to make matters worth.

So did all four of the mark one. Ford was oh for six, which is a pretty bad er. Back in Dearborn there was serious consternation and wonderment about why things had gone so badly wrong. [00:23:00] So Ford created a thing called the LAMA Committee, and I know that sounds like bureaucratic, sort of ask covering sort of like a blue ribbon committee, but in fact, the department heads from each of the major departments at Ford were put onto this committee.

So they had a representative from engine and Foundry and transmissions. And design and even public relations, and they would meet periodically to check on what was going on and to chart course corrections if necessary. One thing they really need to understand is what sort of resources that Ford put into this program.

And it wasn’t just money, even though what Ford spent was unprecedented, that no one had ever come close to spending this kind of money. But this was the first time that a major mainstream manufacturer had ever gone racing in a big time way. Ford was creating a paradigm for what would be used in decades to come.

It’s still being used to this day. And in addition to the money that they spent, they had all these r and d resources that teams like Ferrari or Jaguar, you know, had no access to, you know, they created car craft, I mean, a whole subsidiary for racing. There was an engine cell, a dino cell, where they would run four 20 sevens for 24 to 48 hours.

Not, not just the motors, but they had a attached [00:24:00] to a gear box, which was run by servos so that it could mimic all the gear changes made at Lamont. You know, that was something that no one else had ever thought of doing before, and I, I don’t even know who does that to this day. So it was a, it was a really impressive effort.

I, I just think that’s worth remembering as an overarching theme in this project. Anyway, Lamont committee, they, they came with a couple of important decisions. First, they decided to bag the rest of the 65 season. Their thinking was that nobody cared about places like Spa and Monza. They even heard of them here in the States.

All really Ford cared about was winning lama, maybe to a lesser degree, the American races at Sebring in Daytona. So they decided to forget about racing anymore in 65 and focus on testing and development here in the States. And the testing was relentless. Again, no test program like this had ever been seen before.

And not only would Shelby American show up with all their guys, but Ford would send a bunch of engineers and they also had the vendors show up with engineers, so Lockheed or ING or Goodyear. And everybody would then write up reports, his memos and all these memos will be sent around to everybody. And there’s just stacks and stacks of paper, which are really, [00:25:00] uh.

You know, kind of fascinating to see what they found, all the different things they experimented with and just tried to make work. The third thing they decided to do was not leave all their eggs in the Carroll Shelby basket. And so it was decided to bring in Holman and Moody, which had been the dominant force down in stock car racing to also be involved in the program.

They also brought in Alan Mann over in England and Mann had just won the GT championship, uh, with the Cobra Daytona Cove, so he was brought in as well. Although, to be honest, he was always a minor player. And the other thing that LAMA committee decided to do was to double down on the big block motor. And this was a controversial decision at the time, and there’s still debate about it to this day.

The Brits were convinced that Ford could win LAMA with a small block engine. And I guess you could argue that they did win Lama with a small block in 68 and 69, but that of course was after the unlimited engines had been outlawed. Still, you can make the case that maybe the 2 89 would’ve beaten Ferrari at Lamont in 66.

But there’s a axiom in boxing that a good big man will always beat a good small man. And I think that’s the case with the, uh, the engines. No way the, the small block was gonna beat [00:26:00] the big block car. The big block was too powerful, too much torque, which the drivers love. ’cause that’s what you want coming out of a corner.

And since it was so strong, they could basically lo along it’s 6,000 or six 200 RPM and still go 200 miles an hour. Yes, it was heavier, so it was harder on brakes and tires and all sorts of components. But on balance, I think the 4 27 was the way to go. So they test for the rest of the 65 season. Start the 66 season.

Go to Daytona. It’s a 1, 2, 3 finish. Ruby and Miles repeating their victory of 65. Next race at Sebring. One, two, finish. This is Miles and ruby again. Now in the open top X one should have been a 1, 2, 3 finish. This is the famous race where the infamous race where Darren Gurney was leading his car broke on the last corner of the last lap.

And he was disqualified for pushing the car across the start line. So the teams go to Lama Loaded for Bear. They’re the prohibitive favorites. They have no fewer than eight cars. It’s like an armada. No one’s ever seen before. Three Shelby American cars, three Ho and Moody cars, two Allen Mann cars. They’re the prohibitive favorites going into the race.

But you know, being [00:27:00] favorites also this pressure by being kind of the odds on favorite, and the person who was feeling it more than anybody was Leo Bebe. Leo Bebe was the guy in charge of all of Ford Racing’s programs, and he had been a confidant of Henry Ford II since they met in the Navy during World War ii.

But before Lama Henry Ford had met with Bebe and he’d handed him a note card on which he’d handwritten three words, you better win Bebe understood. This wasn’t like a friendly exportation. This was an order from his commander in chief, and he was going to be expected to fall on his sword if he failed to win Lamar.

This little card meant so much to Bebe that he carried it in his wallet for the rest of his life. So, yeah, he kind of knew you better win before the race starts. Ford meets with all its drivers and they, they give everybody strict orders to run to very conservative lap times. So we’ll finish the race.

And so far as I can tell, nobody paid any attention to these lap times. No, the first lap, this was still when the had the Lamas start when he ran across the track and jumped in his car. Miles’ door didn’t close properly, so he has to pit at the end of the first lap and he goes out and immediately sets a lap record to make up [00:28:00] for lost time.

Meanwhile, Dan Gurney never likes to be slower than anybody in the Ford team, so he sets another lap record while taking the lead. The third Shelby American car was driven by Chris a Amen, and Bruce McLaren. Team McLaren was sort of McLaren’s fledgling manufacturing operation, was sponsored by Firestone.

Everybody else was running good years. During this race, as you can sort of see here, it was, it rained on and off. The track was greasy, called for intermediate tires. It just so happened the Firestone Intermediate was junk. Kept throwing treads, so they lost several laps replacing tires. And finally, McLaren makes the politically in expedient decision to get rid of his Firestones, even though Firestones his sponsor and slap on a set of good years.

And this is when he leans down into the car and tells a amen. Well, what Aon told me, he said was drive the door handles off the door. I believe what Amon told AJ Bain was a go like hell, whatever the point was, they wanted to run flat out to make up for lost time, and that’s what they did. By about halfway through the race, it’s Shelby American Cars 1, 2, 3.

Ferraris are nowhere. It’s Ford’s race to Win. But then shortly after [00:29:00] Dawn Jerry Grant pits from the lead in the car. He’s sharing with Dan Gurney. The water temp gauge is pegged. Head gasket’s gone. Leo Bebe feels a stinking sensation in his stomach. Remember, Bebe’s been through 64 where all three cars have failed.

He’s been through 65 when all six cars have failed. At this point there are four, four gts left. So four of ’em are already gone and all he can think of is that he’s got this, you better win no card in his pocket. And he is got Henry Ford II with this vast entourage looking over his shoulder and he doesn’t wanna screw things up.

So he immediately sends down orders to slow the cars down to lap times of four minutes a lap. They had qualified around three 30 a lap. So this is 30 seconds off the pace. Granted it was greasy on the track and you know it’s an endurance race. Those are lap times that an amateur could be driving at. And Chris a Amen told me that it took him about 15, 20 minutes just to slow down to that pace.

Thereafter, the race ceases to be a race in any sort of what we think of a race. I mean, there was no real competition out there. I. If you look at the, uh, results, and you’ll see that the lead changed hands numerous times over the course of [00:30:00] the last eight hours between the name of McLaren Car and they’re in the black car and the Miles Denny Hume car, which is the second car over there in line.

But it wasn’t because they were dicing for the lead, it was because, you know, their pit stop schedules, they just pitted at different times and they had to pit about every hour for gas. They needed tires periodically. These cars went through brake pads, so they had to make pad changes. Both of them changed rotors before the race was over.

They weren’t really competing. All they were doing was clicking off laps and, and making their way to the finish. Somewhere along the line, someone comes up with a bright idea of staging a dead heat finish. Now, this is to me, one of the great mysteries of Lemos 66, and there’s a bunch of mysteries about this race.

I have no idea who really came up with the idea. Bruce McLaren said he did, but that seems really unlikely to me. And the thing is, I cannot think of a single automobile race that’s ever ended in a dead heat. Uh, not a major one. I can’t think of a single race of any kind that ended in a dead heat. You know, whether it be a horse race or a boat race, or a political race.

The whole point of race thing is to anoint a winner. So I don’t know why anyone thought they were gonna be able to do this, but to Leo Bebe, this sounded like a great idea. First of all, it would be a public [00:31:00] relations coup for Ford. Second of all, it would prevent the first two cars from fighting with each other for the win.

And that was his great fear, was that they would start dicing and they would crash into each other and things would go down the tubes. So Ford Official is, is. Sent over to, uh, talk to the A CO, which is the Automobile Club of the West, which is the I syncratic organization that runs Lama and the French officials essentially say, we’re cool with that.

If you want a dead heat finish, go for it. So Ford of official comes back, he reports to BB and Shelby and all the, uh, the Ford guys. We can do a dead heat finish if you wanna do it. Somewhere along the line, the Ken Miles car had pulled well ahead of the McLaren A Amen Car. And why it did so is is also a subject of dispute Miles fans and Charlie Agape, who’s his, was his crew chief and is still around to this day, are convinced it was ’cause Miles was the faster driver in a faster car.

Bruce McLaren always contended that Miles had flouted team orders and instead of running at four minutes a lap, he cut a couple of quick laps to make sure that he was in the lead when they came down to the end of the race. At this point, it’s [00:32:00] impossible to say what really happened. But the point was before they were to get into their cars for their final stint, both McLaren and Miles were brought over to talk to the board Brain Trust.

And they were told, miles, you slow down. Let McLaren catch up to you. By this time, there’s only one other Ford left, and that was a Holman and Moody car being driven by Dick Hutcherson, who was a stock car Ace, who admitted later he had no business driving at Lamont. He was completely out of his element. I mean, you can imagine also in the rain and at night.

He never even turned right before. He’s in third place, but he’s 10 laps down. So miles and McLaren get in their cars for their final stint, and they start circling around. Miles, slows down, McLaren starts to catch up. Meanwhile, the Ford official comes running breathlessly until the Ford pits and he says the A CO has changed its mind.

They’re no longer going to allow a dead heat finish if the cars finish side by side. The car that has covered the greatest distance will be declared the winner. Now it just so happened that Miles and Hume qualified Second Aon and McLaren qualified fourth. So therefore, Aon and uh, McLaren will [00:33:00] have covered about 20 more feet than the other car, and it would be declared the winner on that basis.

The problem is there are no in-car radios back in 1966, the only way to communicate with the drivers is via pit boards, which are shown at the Moozon hairpin. And it’s pretty hard to get this whole thing in writing. I think while the drivers are going by, theoretically, they could have pitted the cars to tell the drivers what was going on, but no one wants to take the chance.

I think of a, of an unscheduled pit stop for no particularly good reason. And also from Leo, Leo Be’s perspective, all that could happen was bad things if the guys understood the situation, because Miles might be encouraged to start racing with McLaren for the win. And that’s exactly what he didn’t want to happen.

Again, there are a lot of people who think that Bebe purposely screwed miles out of the win, and I find this a little difficult to believe. I mean, miles was a little difficult personally, and I guess you could argue that he had floated team orders earlier in the race if he did fly team orders earlier in the race.

But you know, he’d been a stall water of the program. He had done most of the testing and development. He knew the Ford guys really well. He was coming off winds at Daytona and Sebring. I mean, I don’t see any reason why they would’ve wanted to hang him out [00:34:00] to dry. I think Bebe’s issue was he didn’t want anything to go wrong and he didn’t particularly care who won the race as long as a Ford won the race.

And from his perspective, it was safer to do nothing. So he did nothing and the cars continued on to the finish. And this is the famous finish. You know, in this photo, as you can see, this is, uh, McLaren leading with miles lagging back. And so there are schools of thought that say that McLaren goose the throttle to steal the victory.

And some people claim that Miles purposely held back to show his disgruntlement at Ford for denying him the victory. In fact, miles says that the real finish line is actually back about 10 yards from there. And he said when they crossed the timing line, there was actually a, a wire that they were as close to being dead even as they could.

And nobody knew what was going on in the pits. I mean, even in the Ford Camp, they weren’t exactly sure what was gonna happen. There’s a fellow here, bill Benet, who’s actually there in 66, who was actually there while this was going on. Nobody in the stands knew what was going on. Chris a Amen in the pits didn’t know what was going on.

He didn’t realize that he was the winner until they started pushing him toward the victory roster. On the other hand, Ken Miles thought he had won the race and he actually [00:35:00] tried to drive his car to the victory rostrum, and he didn’t realize that he was second until they wouldn’t let him go there. So, and Ford couldn’t have cared less either way.

I mean, to the United States, no one had heard of any of these guys. I mean, you had, uh, a transplanted Britain, three guys from New Zealand, all the people in the United States knew that a Ford had won, finished 1, 2, 3, vanquished Ferrari mission accomplished, which is why Henry Ford is the only guy who looks really, really happy here on the victory, ROS, that’s Amen.

And McLaren, and to me, their smiles look a little bit sheepish. A couple of minutes after that, miles and Hume are more or less pushed onto the rostrum, and there’s a pretty telling photo of Miles who looks like he’s grinning his teeth while he’s grinning. Clearly not happy to be there. The only person who looks really elated is Henry Ford, and that’s important to note because I.

A week before the race, Henry Ford had told reporters he figured this would be the end of the program after Lamont. And when you think about it, this was the perfect place to end the program. They just finished 1, 2, 3 beaten Ferrari, you know, done everything they’d set out to do. All that could happen from now was things could go downhill.

The thing is though, racing is a brutal, cruel sport. So many [00:36:00] things go wrong so many times that when you win any race, I mean even at the Lowliest club level. You’re just so happy. At least I’m so happy. So you’re just elated. And you can see Ford here. He’s just jazzed by the whole thing. And he’s so amped that when they ask him, well, what are you guys gonna do now?

He says, we’re gonna come back and do it again. And I think this came as a surprise to all the people at Ford. I don’t think anyone really intended to really figure there was gonna be a 1967 program. So a lot of people that sort of the Ford saga ends here, but I actually like the rest of the story, which is just one more year.

’cause to me, it’s the best part of the story, even though it’s sort of a postscript in some respects. After Lama, a man is let go. Holman and Moody plays a, a larger role in testing and development, and they incorporate a lot of NASCAR technology into the race car. Most notably, there was a heavy duty roll cage, and this turns out to be a big deal, at least in Peter Revson because it’s thought to have saved his life when he barrel rolled his car during testing at Daytona.

And there’s again, they test and test and test and test, and they do so much testing that they rename the cars as, uh, mark two Bs. The six, six cars were called Mark two a’s, but at any rate. Ford goes to [00:37:00] Daytona to begin the 67 season and they figure they’re gonna have more of the same, gonna be Ferrari again, gonna be a nice easy year.

Instead, they run into a buzz saw and it’s called the, uh, the Ferrari three 30 P four, A gorgeous car. It’s a car that sounds spectacular. It’s agile, it’s fast, it’s as iconic in its own way. The P four is as the mark two was. At Daytona Ford has a catastrophic race output. Shafts for the transmissions were improperly.

He treated and every one of ’em fails. Only one car finished the race and it was way back. The Ferraris finished 1, 2, 3 and they managed the picture perfect. Uh, line of breast formation, you know, at the finish. That Ford kind of botched there at Lamar. To add sort of insult to injury after the race, Chris, a Amen who had moved over to the Ferrari team said the, uh, Ford handled like a truck compared to the Ferrari.

So the four guys weren’t too happy. But besides being humiliated, there were also a sense of, well, what do we do now? They just spent. Six months developing. You know this Mark two B, and it had just been trounced by Ferrari at Daytona, and it’s conceivable [00:38:00] the Mark two might’ve been able to beat Ferrari Lama, which was attractive, favored the Fords, but it definitely wasn’t a done deal.

So Phil Remington came up with a plan B or sort of a Plan J, as you might wanna call it. And I gotta backtrack really briefly to why that is. So from the very beginning of the program, everyone understood excessive weight was the biggest issue with the four gts. And there have been all sorts of efforts to lighten the cars.

They used aluminum body work and actually aluminum chassis, they cut the tops off. But eventually a uh, Ford engineer by the name of Chuck Mountain, who had been one of the guys who had gone over to England in 63 to work on the original car, found a company in western Massachusetts called Brunswick. And it made a bunch of consumer products.

One of them was actually bowling pins, believe it or not. I think it was those A MF bowling pins. But they also were a major department of defense contractor and they were building instrument panels for fighter jets out of a aluminum honeycomb material that was very light, yet very rigid. So mountain thought it might be possible to build a Monaco, added this.

Material. Ed Hull, who was one of the unsung heroes of the program, built a chassis where he used honeycomb aluminum. It was bonded with, uh, an industrial [00:39:00] grade glue that was cured in a high temperature ovens, very similar to the auto Clay is used now to, uh, make carbon fiber and around this Monaco Ford styling put together a radical looking body work.

It had these protrusions at the front that looked to me like lobster claws. And it had this high long rear deck, which has actually been modified here a little bit already, but it resembled a bread van. They dubbed this to the J car. And the JCAR actually was slightly faster than the Mark two, but only slightly.

And most of the drivers, well actually all the drivers except Forman preferred the Mark two. So it was decided to raise the mark two in 66 at lama, and that was the right call. Obviously they finished 1, 2, 3, but they continued to test the jcar after Lama. And so Ken Miles was in the car at Riverside in August.

They’re testing two experimental, semi-automatic transmissions and on the back stray while he was doing something like a buck 80 or something like that. Car goes outta control. No one to this day knows exactly why. All sorts of theories. Some people say they thought the body work was aerodynamically unstable.

I find it hard to believe. Some people thought the honeycomb aluminum actually came apart in in the Monaco. Some [00:40:00] people think the brakes locked. I think the most likely thing was that the transmission froze in gear rate. The car goes off the track, high speed barrel rolls, miles is ejected, and he’s killed on the spot.

And that’s probably the lowest day in the history of the Ford GT program. And that also ends, as you might imagine, a development of the JCAR until Daytona 1967, when Ford has nothing else in its cupboard to beat Ferrari. So Phil Remington comes up with the idea of using the jcar. He thought it was a good chassis and he thought the problem was the body work, which he suspected was very draggy, is the way he put it.

So Remington flies to Dearborn with two of his top fabricators and they take the car into the wind tunnel. And Remington literally starts hacking away at the body work and reshaping it totally by intuition into the shape that he thinks will work well. He gets finished, they run the car through the tunnel.

The numbers look good. They immediately shipped the car out to Kingman, Arizona high speed test track that Ford has out there straight outta the box. The uh, mark four is five miles an hour faster than the mark two. So Ford decides, Hey, we think we’ve got something here. They named the [00:41:00] car of the mark four and the reason why they didn’t name it the mark three was because the mark three was the name reserve for, there was a street car version of the GT 40 of which they built, I think seven total.

Ford decided to have a kind of gong show bake off between the mark four and the mark two. Uh, at Sebring whole new Mark four is built up. Shelby American was running with Mario Andretti and Bruce McLaren Holman and Moody was running a, uh, one of the Mark two Bs. McLaren puts this car on the pole and then races with the Chaparral.

There’s a, they dice for a couple hours until the Chaparral breaks, and the mark four wins easily. The mark two is literally miles and miles behind. This is one of the rare occasions where a car straight out of the box wins its first major race anyway, and the Mark IV actually only raced two races, and it won both of ’em.

So I had a pretty good winning record. After Sebring Ford decides to build four brand new Mark fours. I mean the resources they had at their disposal were were pretty incredible. This is the Gurney Ford car, though the really famous one, which is still owned by Ford, the only one that they still own. And Ford goes to Lamar with four mark fours with two mark twos as [00:42:00] backup.

McLaren puts one of the mark fours on the pole, but the Ferrari and Chaparral are right there, and clearly this isn’t gonna be a cakewalk this year. First of all, remember Ferrari had crushed the Fords at Daytona and they’ve been faster than the Mark four in the Lamont test. Chaparral was the most sophisticated race car in the world in 1967.

This was the two f, the high wing car with the adjustable wing and, and the Semiotic matter transmission. So, you know, Ford had a real race on its hands. It wasn’t like 66 where they were just waiting for the Ferraris to fail. McLaren’s on the pole. The, the Chaparral Ferrari’s right there. The slowest Mark four, strangely enough, is Dan Gurney.

Since then, there’s sort of this mythology that has grown up that Gurney was sandbagging ’cause he didn’t wanna embarrass his co-driver. AJ Foyt Gurney denies that this was the case. Foy was not a very experienced road racer, but he was AJ Foyt. I mean, he was gonna go fast and he did go fast. What happened was that Gurney was consciously following the example of his friend Briggs.

Cunningham and Briggs was not a very fast driver, but he always finished at Lamar. Whereas Gurney had D nfd in seven out of his nine races there. So Gurney may decided that he was gonna go slow and he was gonna [00:43:00] especially go slow in the break zone for the moles on Hairpin. Well, what happened was the cars were going 215 miles an hour down the street.

Then they had to break down to about 35 miles an hour for the hairpin. And you can imagine how hard that was on brake pads. Also, the brakes would get extremely cool on the mul on strait and when they would get, when you hammered the brakes, the rotors had a tendency to crack. So what Gurney decided to do was, instead of breaking at the 300 yard mark or whatever it was, he decided he could lay brake at, he was backing outta the throttle around 600 yards out, letting the aerodynamic drag slow the car down to about 160 miles an hour.

Then he was lightly getting into the brake pedal, slowly build up temp so that the would preserve paths and, and save the rotors. The other reason why he wasn’t particularly fast during practice was he was adamant about making the car handle well through the Olson kink. The cars were dead flat through the kink, even at 250 miles an hour.

But when the car wasn’t handling well, it was a bit of a handful. You really had to concentrate, you had to use all the road, and that was a problem. If it was, you know, when it’s dark, it. It might start raining. There was always traffic at Lama Gurney. Wanted to make sure he could get through the kink, literally with one hand on the [00:44:00] steering wheel.

So he worked for a long time in practice, fiddling with the suspension and adjusting the rear spoiler until he transformed the car into what he described. The handling as being like a big American luxury car, you know, it was perfectly stable and a really comfortable, and just gobbled up miles. That’s how he was ready to go and the race begins.

Ronnie Bucknam takes the lead in a, strangely enough, in one of the marked two vs. And he holds the lead for the first hour, but Gurney was behind him and he thought that Ronnie was driving pretty hard to stay there. Gurney takes the lead after the first hour and he and Foyt lead for the next 23 hours.

At one point there were eight laps ahead of the lead and all the other fors run into trouble. Mario Andretti famously crashes in the Ss. Both of the mark twos get caught up in his crash. So there are three for wrecked in like literally one minute. Lloyd Ruby beaches, his mark four in the sand. McLaren loses the body work on his mark four while he is on the mos on straight.

Then he has to go back around. He has to go back out to find it loses a whole bunch of time and he finished way back. So while these guys were in the lead, the Ferrari are the best of the rest, and the Ferrari were really good, but [00:45:00] they weren’t fast enough to catch Boyton Gurney. So Ferrari realized their only hope of winning the race was to break the Ford.

Mike Parks in the P four was sent out to Harry Gurney into driving faster than he wanted or ought to drive. Parks got behind him and he started duking back and forth and flashing his brights, and then he would outbreak him in the brake zone at the moozon hairpin and a down your arage, generally behaving like what?

Uh, gurney called a pain in the ass. Gurney got tired of this and after a couple of laps when he got to Arage, which is the slow right hander on the backside of the circuit, he pulled off the circuit and he parked the car and he just sat there in a neutral with the engine running and parks pulls off behind him and the two cars are sitting there.

And to me that I think this is the most surreal moment in the history of automobile racing. It’s the middle of the 24 hours Oma. And the cars running one, two are sitting on the side of the road, like Uber drivers waiting for their fares to show up. So I love that. But Gurney was content to sit there as long as parks wanted to sit there.

So after about 10 or 15 seconds, parks finally takes off. [00:46:00] Gurney takes off after them, and the race proceeds to the finish. They didn’t run very hard there after they didn’t have to. They won by, I think, four laps, set a new record. Foy took the last stint. That picture at the beginning was, if you recall, there was gurney sitting on the hood as they went to the victory rostrum.

And here they are at the rostrum. Where Gurney famously shakes up his magnum of champagne, pops the cork and sprays the crowd. Supposedly, this is the first time anyone had ever done this before, and this started a tradition that for better or worse exists to this day. This was the capstone of the of the Ford Factory effort.

About a week after this, Don Fry announced that Ford was getting out of Lamar racing. Ford had actually prepared, they had plans for the 68 season, but they shelved them. They didn’t wanna spend any more money. What more could they do? Shortly thereafter, the CSI, which as I recall, was the predecessor of the FIA or somehow, I don’t know the exact relationship.

I’m sure Don knows they changed the regulations and they outlawed unlimited sized engine. They did make a little bit of a mistake there. They created group four where they set the engine limit at five liters and they said the course had to be homologated. Well, as it turns out, the GT forties, of which [00:47:00] there were, you know, more than a hundred out there, easy to homologated and ran a small block, five liter motor, two 80 nines, and also three oh twos.

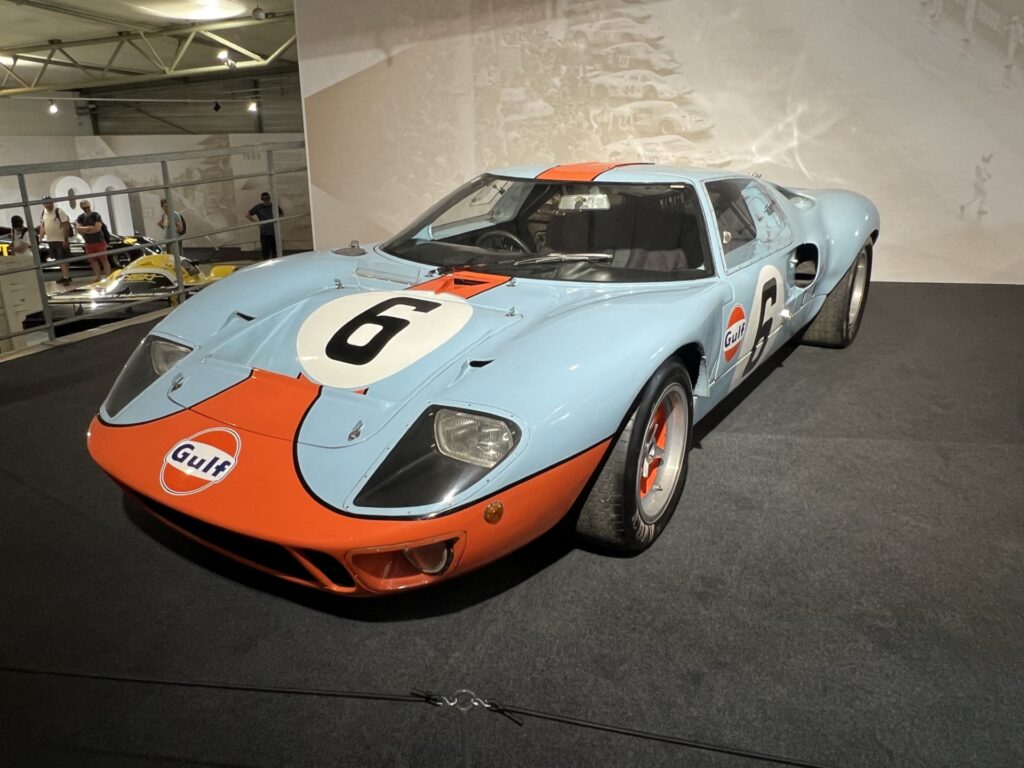

So John Wire took GT forties and he got himself some Gulf sponsorship and he went to LAMA and won in 68 and 69 with small block GT forties. So Ford wins LAMA four years running. This is the greatest American Achievement Ivy League in international road racing. Most of the Ford people, and I suspect most people generally think the 66 is the best victory.

Personally, I like the 67 win. Genuinely all American car, all American drivers, really competitive race and tremendous performance. So that was the end of the Ford program. And again, first time really a mainstream manufacturer had gone racing and Ford set the bar pretty high. To this day, I think everyone who goes big time auto racing is tries to match the achievements of Ford.

We’re gonna open the floor to questions if anybody has any questions, but I did wanna mention a couple of names here. First, Jim Vogel, who’s the owner of the GT 40, the Mark two, which is the um, 66 winner, and he’s here, and that’s his car over there in the lobby. Bill Vanay, who pointed out before, who was here in 66, and [00:48:00] also Calvin Lane who was here somewhere, I didn’t see him, but he was there at Lamont 64, saw the cars run.

So if you guys get a chance, you should chat with them a little later today. Anybody has any questions, just lay ’em on me and I’ll do my best.

Don Capps: Where is the Mark iv?

Preston Lerner: The Mark iv. It’s very interesting ’cause Ford didn’t understand, I think what they were doing and they had no interest in their history. The actual 66 winner ended up being sold, but the Mark IV they knew was a big deal and they kept that.

It’s in the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn to this day. It’s never run since 67. And actually there was some damage in transport a couple years ago and it was sent to all American racers and Dan Gurney’s team actually did the restoration of the car,

Don Capps: the minor point. But

Preston Lerner: yes.

Don Capps: Uh, I worked in the, a division of 3M in 1961, and at that time I was led to understand that that was a well established aerial technology.

At that time, we were making the diesel. Oh, really? But we were making the, that’s how I came across. But that was a well established technology, lot of planes in the air using technology. [00:49:00]

Preston Lerner: Yeah. I find it hard to believe that the. Failed. I mean, but I think this is interesting ’cause this is the era when, again, where aerospace technology is making its way over to motorsports for the first time.

I mean, now we take all that stuff for granted, you know, this is when it was really starting to happen. Did FO defer to gurney? I mean the car set up. Yeah, absolutely. Fo explicitly said, you know, whatever you wanna do is fine with me. And I have to confess that Floyd’s one of the only people that I was never able to talk to.

I’ve actually tried to talk to, I did a book on the SC. Don mentioned a couple years ago, and he wouldn’t talk to me about that book either. I don’t know, and I don’t know why I’ve talked to him about other subjects, the road racing stuff he never would talk about. I don’t, I have no idea why, but yeah, I mean, he clearly understood he was the junior partner in that team, but I, I just wanted to disabuse people with the idea that fight was some neophyte out there.

I. I mean, you know, he was probably the greatest driver in America at the time. He had just won Indy like two weeks previously. He had actually raced the scabs pretty successfully. He rear engine scabs in 64. So his problem was he’d never been to Lamar before, never raced at night before, and he didn’t get any [00:50:00] practice time because the windshields which were made nearby in Corning kept breaking during practice.

So, uh, that was one of the problems they had that year.

Audience: Question regarding the rivalry between Ford and Ferrari. I really kicked around that there was a point in time that Ferrari either attempted to or canceled or raced. It was supposed to occur in Italy in, uh, in an effort to avoid being embarrassed by Ford.

Is there any any truth to that?

Preston Lerner: I believe I have to. How they prevented the Cobra Daytona coup from winning the GT Championship in 64. And I don’t remember the details, but yeah, it was like some chicanery that Enzo, uh, cooked up to make sure that they kept the championship. The two 50 GTOI think won the championship and it was long in the tooth by that point, but nothing like that happened in Lamas stuff.

But there’s only ’cause Ferrari couldn’t come up with any solutions. I guess he would’ve done it if he could’ve,

Tom Weidemann: he would’ve been quarter about all.

Audience: Second question, how long were these run on the circuit? I remember one came in the, in my mind. Was [00:51:00] it?

Preston Lerner: Oh really?

I don’t think so. First, uh. Uh, yeah, Henry’s, uh, Italian wife, a very glamorous, supposedly she placed a bed on Ferrari in 67, I think, or 66, but, uh, I don’t know how well that, that didn’t go over too well, apparently with the Ford guys. I’m not sure how long the GT fours were raced for. I mean, it was a, it was a long time, you know, again, you might wanna look, the Ronnie Spain book is really well done and, and there’s several other books that sort of deal with the private tier years.

I don’t recall having any habitual, you know, systemic problems with fires in those cars. So maybe that was just a bad deal there in Mexico City.

Don Capps: Part of that is the safety regulation change. 70, you’ve got to have certain types of, uh, protections in the fuel tank, that type of thing. Uh, there other, uh, issues that really by 70 71, they were, uh, technically safety wise becoming obole upgrade.[00:52:00]

You go out, buy another car because by then they.

Preston Lerner: I’m happy to answer more questions though. You know, we go over there if you wanna ask me anything informally, but if not, I really appreciate you taking this time. It was a pleasure for me to do this.

Thanks.

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports spanning continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers race series, and race cars [00:53:00] captured on their shelves and walls, and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show [00:54:00] or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be [00:55:00] possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Welcome and Speaker Introduction + Don Caps’ Remarks; Preston Lerner Takes the Stage

- 04:55 The Birth of the Ford GT40

- 05:24 Ford’s Racing Strategy

- 06:19 The Ferrari Negotiations

- 08:25 The GT40 Development

- 13:06 Challenges and Early Races

- 16:42 Shelby American’s Involvement

- 21:45 The 1966 Le Mans 24 Hours

- 30:25 The Controversial Dead Heat Finish

- 35:05 Post-Race Reactions and Ford’s Future Plans

- 36:22 The 1967 Season and Ferrari’s Challenge the 330 P4

- 39:36 The Tragic Testing of the J-Car

- 40:53 The Mark IV’s Triumph at Le Mans 1967

- 46:29 Ford’s Exit and Legacy in Racing

- 47:45 Q&A Session and Closing Remarks

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

Despite its racing success, Ford discontinued its factory Le Mans effort after 1967. However, GT40s continued to race, securing additional victories in 1968 and 1969 under John Wyer’s Gulf-sponsored team. The car’s impact persisted—decades later, Ford resurrected the GT program, leading to its historic comeback win at Le Mans in 2016.

Today, the GT40 remains a symbol of engineering ingenuity, motorsport determination, and Ford’s historic rivalry with Ferrari. Whether through aerodynamic advancements, mid-engine design philosophy, or raw American horsepower, the GT40’s legacy has shaped endurance racing for generations.