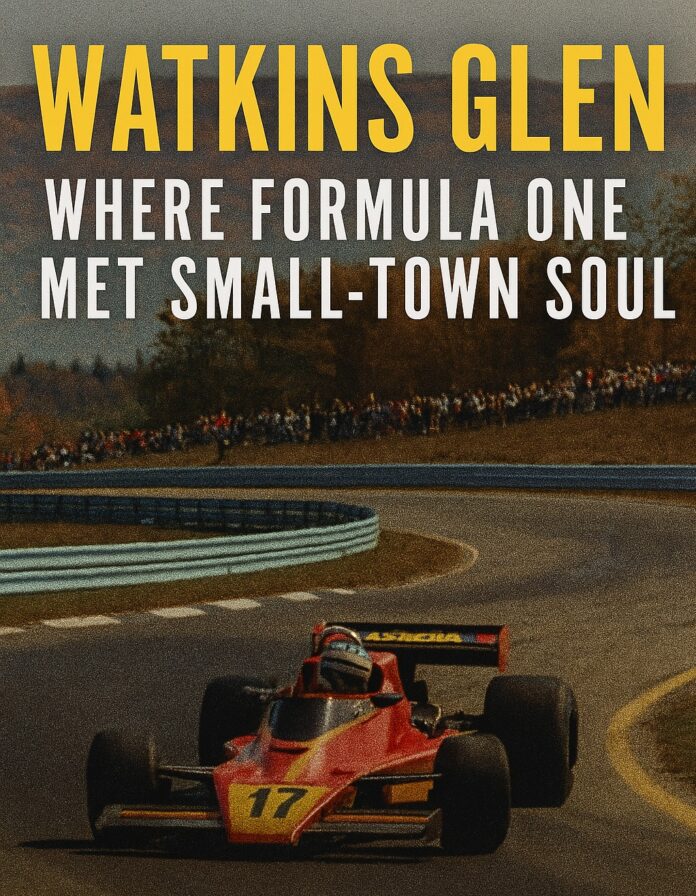

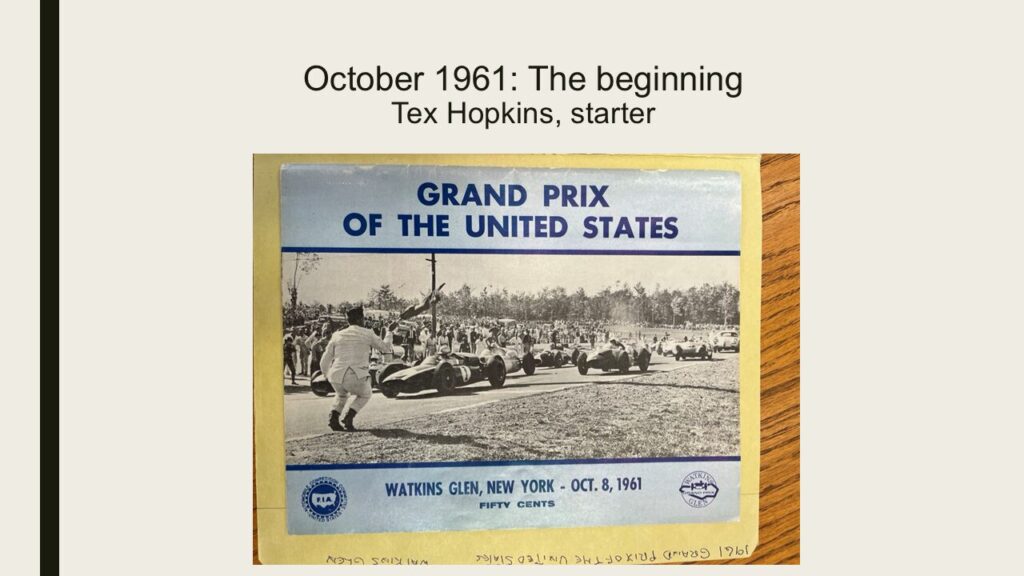

In the golden age of Formula One, nestled deep in New York’s Finger Lakes, a curious anomaly unfolded: the world’s most elite racing series made its American home in a village of fewer than 3,000 people. From 1961 to 1980, Watkins Glen hosted the U.S. Grand Prix, earning accolades from drivers and fans alike. But behind the glamour and grit of the Glen lies a story of collaboration, conflict, and cultural collision.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

Dr. James Miller, professor emeritus and motorsports historian, paints Watkins Glen as a case study in contrasts. On one side stood the “sporting gentlemen” – wealthy, Ivy-educated cosmopolitans drawn to the ritualized masculinity of European road racing. On the other, the Glen’s residents – rooted, civic-minded volunteers who saw the Grand Prix as a community endeavor.

This unlikely alliance birthed a racing legacy. But as Miller argues, the very differences that made the partnership powerful eventually tore it apart.

Bio

Dr. James Miller has a longtime interest in media technology, and this led him to the historical study of the automobile as an under-appreciated site of media consumption. From there, the highly digitalized modern race car presented itself as a possible precursor of future mobility. This was also an excuse to intellectualize the pleasure of motorsports, which has resulted in a connection with the IMRRC and membership in the International Motor Press Association. Miller is professor emeritus of communications at Hampshire College, a former member of the graduate faculty at UMass Amherst and a member of the Porsche Club of America.

Synopsis

This episode of The LogBook – our History of Motorsports series – features a lecture by Dr. James Miller on the history of Formula One racing at Watkins Glen from 1961 to 1980. Miller argues that the collaboration between sporting gentlemen and local residents made the event possible but that ultimately, their differences led to the event’s decline. The episode covers the origins of road racing in Watkins Glen, notable figures involved, the town’s socioeconomic context, and the tensions that arose between local organizers and the globalizing forces of Formula One. Miller also speculates on the possible outcomes had different decisions been made.

Follow along using the video version of the Slide Deck from this Presentation

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argo Singer Family

Crew Chief Eric: Formula one at Watkins Glen Sporting Gentleman in a small town by Dr. James Miller. When James Miller attended F1 races at the Glen during the 1970s, it was for fun. Now they have become the focus of social and historical analysis. In fact, the 20 years of Formula One at Watkins Glen from 1961 to 1980 are worthy of subject.

They afford a case study of the transitional racing era between the near amateurism of the 1950s and the increasingly commercial globalizing periods that followed most especially Formula One at Watkins Glen is anomalous. How do you explain a Finger Lakes village hosting the mostly European pinnacle of Motorsport and be remembered by Jackie Stewart as the most nostalgic US Grand Prix?

That [00:01:00] Formula One ever had? One answer is the unusual collaboration between Patricia Enthusiasts, community leaders and the volunteer spirit of a small town, an effort that began in 1948 with the first race through local streets and roads. Dr. James Miller is a professor emeritus of communications at Hampshire College, and a former member of the graduate faculty at UMass Amherst, a senior researcher at the I-M-R-R-C.

He’s a member of the International Motor Press Association.

Kip Zeiter: Our next presenter is James Miller, who’s gonna be talking about Formula One, a Watkins Glen Sporting gentleman in a small town.

Jim Miller: The 20 year history of the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen was bookended by two dramatic events. The first was the approval in August of 61 for the event to take place, leaving only six weeks before the October race date.

The second occurred in the spring of 1981 when Formula One at the Glen was removed from the racing calendar due to its inability to pay participants from the previous race. [00:02:00] A year later, the track was sold at a bankruptcy auction. Over time, it became clear that what made both the first race possible and the apparently sudden demise inexplicable, was the remarkable collaboration between organizers and Glen residents, local civic leaders and racers found common cause with villagers of all sorts.

To bring about an annual international extravaganza that drew hundreds of thousands of spectators to what remains the longest running venue of Formula One Grand Prix racing. In the US three times, formula One drivers voted the Glen the best organized race of a season. It was cooperation between these two distinct groups.

Organizers and local residents that made it all possible. The truth of this familiar claim is not denied by adding a paradoxical complication that in the end, the group’s differences were stronger than their shared interests. This may have been discovered only too late, and that’s what I’d like to argue today.[00:03:00]

In 1969, camera and Argetsinger proposed to the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation that he and private investors buy the track. In order to finance the continuing improvements necessary to hold Grand Prix racing, his proposal was rejected and Argo Singer left the organization. This, it turned out was the beginning of the end, even though a full decade of racing remained.

My view is that Argo Singer and his allies understood road racing in general. And the Grand Prix in particular, in ways ultimately at odds with local members of the corporation and maybe some villagers. I’m going to label these two groups, sporting gentlemen and residents of a small town. My point is not to assign blame, but to offer an explanation that goes beyond mere finances for what many of us see as a tragic outcome.

Sporting gentlemen brought an orientation to road racing that had relatively little to do with the geographic location of a circuit or its benefits to a local [00:04:00] community. They were primarily about masculine competition in the context of highly ritualized upper class games. With serious but amateur traditions.

These were learned in prep schools, private colleges, and Ivy League universities and yacht clubs and country clubs, and in sports like golf, dressage, sailing, and the like. They were cosmopolitans attracted to the involvement of European cars and drivers. In American racing, many possessed the business savvy of wealthy people and had a feel for both the scale of capitalization and political skills required to pursue road racing.

Early road racing circuits were necessarily located in the rural countryside, of course, but were nearly always near metropolitan areas. Where sporting gentlemen lived Lime Rock in 56. Well, that’s New York Bridge, Hampton 57, the other side of New York City and Elkhart Lake 59 in Chicago. Small town people were less likely to be racers [00:05:00] were, by definition rooted in their village, happy to volunteer their efforts that in turn produced benefits for the community.

Maybe they were possessive about keeping the Grand Prix synonymous with the people of Watkins Glen through maintaining what they saw as local control of the event. Here’s how I’ll try to make my case. First, the small town. This will necessarily be a broad brush treatment of the American small town, especially in the second half of the 20th century with reference to the Glenn and a few key local organizers of different sorts.

Next, a presentation of sociologists, Digby bolt sells sporting gentleman notion, and three organizer racer biographies that I think illustrated. Third, a two brief account of the fatal collision between sporting gentleman’s sensibility and small town attitude that ultimately brought an end to Formula One at Watkins Glen.

And lastly, some counterfactual. Historical fun, focusing on camera and aring, and the recent development of Formula One [00:06:00] Grand Prix Racing. The American small town has a double identity, one mythical and the other historical. The first is profoundly nostalgic, a celebration of an idealized past. The other is more complicated.

One historical fact is at the turn of the 20th century, about three quarters of Americans lived in small towns. Perhaps out of this widespread experience. Grew an outside imaginary significance. In fact, a study in the twenties and thirties, fiction in widely circulating magazines found that farms and small towns were depicted as enjoying a way of life whose essential goodness contrasted with the evils lurking in big cities.

But as early as the 1880s. There was concern for the future of small towns that were bypassed by commercial roots or emerging industries. And around the time of those magazine stories, the census reported that for the first time, city dwellers constituted the majority of the US population, especially during the post-war period.

The rural small [00:07:00] town was under existential threat, industrialized agriculture transformation into bedroom communities. Outmigration in search of better opportunities. Greatest population loss occurred from the thirties through the seventies. One estimate is that between 1950 and 1970 towns the size of the Glen lost one third of their local retail businesses.

In the early fifties, one of the most important American community studies took place nearby in the wonderfully named Small Town of Candor, New York. Arthur Viic and Joseph Besman described a kind of collective delusion that candor was actually the master of its own fate. They also revealed a shared illusion of democracy when actually a limited number of influential citizens called the shots, and when church members organized most of the town’s public life.

They termed the crisis of the small town modernization, by which they meant an often unwelcome intrusion of outside influences that were imposing [00:08:00] new ways of living. These inescapable authorities ran the gamut from radio and TV to national retailers to state level offices of education. Watkins Glen would not have been immune from these unsettling dynamics around the time that road racing arrived.

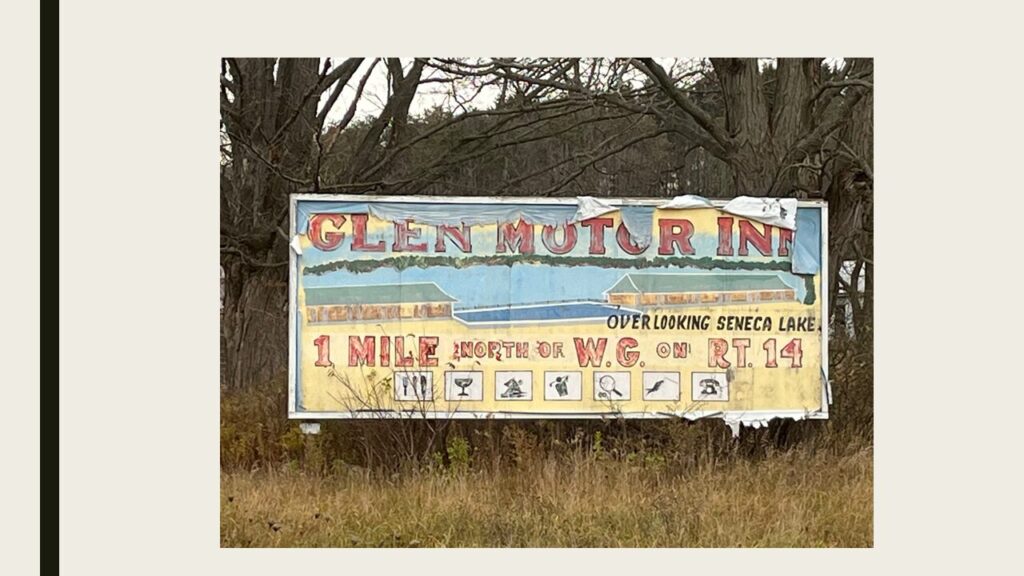

Part of racing’s allure all the way through the F1 years was surely a manageable antidote to forces that threatened a deeply established, rewarding small town way of life. Watkins, as it was long called. Shares the features of many other small rural towns of upstate New York for decades. However, schooner and steam ferry boats crisscrossed Seneca Lake, facilitating local travel and trade and bringing visitors.

By the end of the 19th century, the boats had been replaced largely by the railroad, which then brought international guests to the curative waters of the very grand Glen Spring sanatorium and hotel. Next door to its 300 acres. New York established a state park in 1906. [00:09:00] Its centerpiece is a 400 foot deep gorge.

That, along with a score of waterfalls, was given pride of place when the town literally changed its name in the 1920s to Watkins Glen. During the Grand Prix years, the Glen’s population was less than 3000, except for the unusual production of salt from brine wells. The local economy depended on tourism, agriculture, and retail.

The first bank was built in 1922, the first cinema. Two years later, the municipal building, A New Deal project housed the fire and police departments and the mayor’s office, the court, and also the library. Another depression area intervention was the Civilian Conservation Corps, which established several local camps where young men work to improve the state park, making it more accessible and more beautiful.

Jean Argetsinger in her history of the local Catholic church says that the Erie Canal and the local Mong canal, and later the railroads brought waves of immigrants to the Glen [00:10:00] to work as loaders of coal barges, stone masons, farmers, and at the hotel jobs. First the Irish, and then in larger numbers, Italians joined the descendants of the early British settlers.

The primacy of tourism, a seasonal economy that encouraged openness to visitors was threatened when the luxurious Glen Springs founded in 1890, closed its doors during a war after Cornell briefly housed GI Bill students there. It became a Catholic seminary in high school for 20 years and then was abandoned.

Perhaps the loss of the resort was an incentive to try to extend tourism into the autumn, which was a rationale for October road racing and, and later Formula One. During the fifties and sixties, regional tourism promotion became an organized effort using Finger Lakes to brand the area. It emphasized boating and camping and stressed the ease of transportation afforded by the new interstate highways, Cornell University, even established and Office of Regional [00:11:00] Resources and Development.

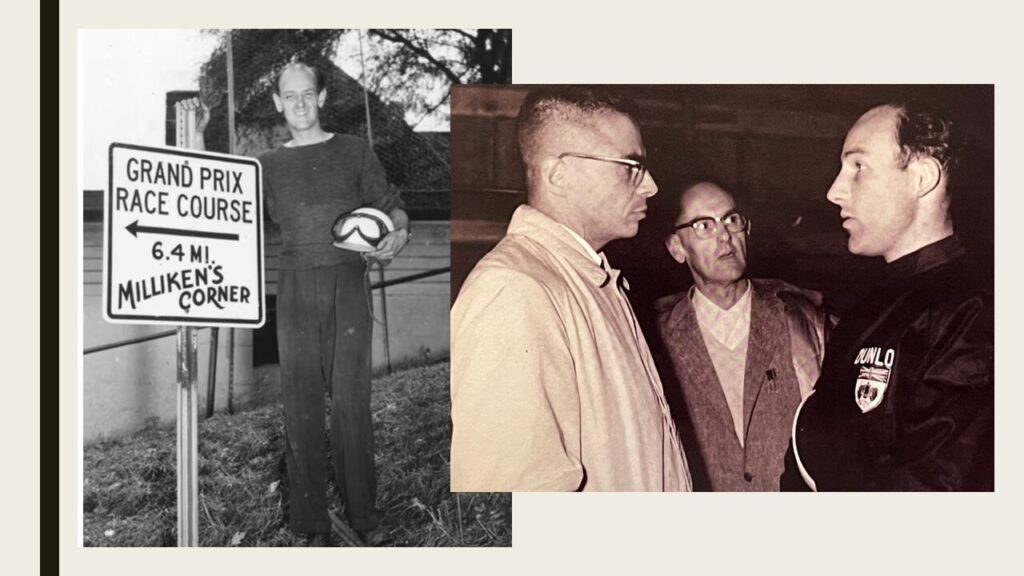

Here are biographical sketches of five men with different sorts of local identities who were involved in racing. Donald Brubaker brought his five children to the Glen in the forties to start a new life. After the death of his wife, he had connections here, new Yorker cartoonist, Sam Cobe, a friend of Cameron Argetsinger, who lived in the village was his cousin.

Brubaker was a graduate of Penn’s Law School, but he became proprietor of the Seneca Lodge, whose food he grew organically. The lodge was famous for housing, F1 teams, and its raucous post-war celebration. Active in promoting local tourism. Brubaker became president of the Chamber of Commerce. Malcolm Curry came to the Glen from Massachusetts and with a partner bought local newspapers beginning in 1951, which they published until 1987.

He later succeeded Argetsinger as executive director of the Grand Prix Corpor. Henry Valent was the son of Italian [00:12:00] immigrants and a native of the Glen. He graduated from Cornell and its law school later establishing his own practice in town. He was co-owner of the local AM and FM radio stations and like other leaders, he was active in a number of organizations from the Chamber of Commerce to the Board of Education and the area hospital.

Liston Kuhn was born in a rural hamlet near the Glen. His father was a farmer and male carrier and his mother, a teacher. After a short period following the war teaching school, he attended Cornell’s law school and he practiced law in the Glen. Later he was elected district attorney and county judge, and served for decades in the Air Force Reserve and was active in the county Republican party and other organizations.

Joe Fran’s parents were Italian immigrants. He and his wife Helen, built tourist cabins during the late thirties on the family farm along the lake. After the war, they established the Glen Motor Inn, which featured 40 rooms or restaurant and a pool. It became a storied [00:13:00] lodging place for Grand Prix teams and operated until just a couple of years ago.

They donated land that became the local golf course. Where Joe taught Formula One drivers how to play the game, he too was president of the chamber and their son Vic was himself a racer and a racing team owner, sporting gentlemen, is Digby Bolt sells term for the tradition of gentleman amateurs, upper class Protestants, mostly who followed conduct imported from aristocratic England at its core is the idea that games demanded loyalty, self-discipline, and a sense of command and accomplishment.

Their code of conduct stress quote, winning is less important than playing hard and fairly in the states. The newly formed national upper class of the 19th century steel and railroad economy imbued these values in its sons by means of Episcopal boarding schools in New England and the originally Calvinist colleges of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.

So to say, sporting and gentlemen, implies social [00:14:00] position. Competitive, but rule abating, masculinity, a deeply socialized sense of how to play well, certain valued games, and a shared sense of camaraderie among the select few. Both cell even suggests that underpinning this orientation is the unstated view that sporting gentlemen possess the natural fitness to rule.

Three biographies of sporting gentlemen capture its varieties. The closing weeks of the 19 39 40 New York World’s Fair featured a race of 18, mostly European sports cars, over a seven 10th mile circuit between the exhibition buildings. The winner who averaged 35 miles an hour was 26-year-old Frank Griswold Jr.

Months before he owned a car that ran in the Indy 500, and in 1948, Griswold won the first road race at Watkins Glen. He ran a machine shop outside Philadelphia and became the North American importer for Alpha Romeo Weber Carburetors and Nty Steering wheels. Frank Griswold Jr. [00:15:00] Grew up on the family’s 34 acre estate on Philadelphia’s main line.

In Harvard’s class of 18 94, 20 fifth anniversary report. His father identified himself as a retired banker and broker, and his club as the Racket Club, which today says, quote, continues to be one of the most prestigious private city clubs in North America. Griswold’s parents and grandparents appeared in the 1917 social register.

They were said to season in Bar Harbor and Newport of Palm Beach and in Europe. Finally, it seems likely that the extensive Wikipedia entry for the Griswold family refers to Frank’s relatives who first arrived from England in 1639. William Milliken Jr. Was born in 1911 in Old Town Maine, a town known for canoe building and paper making.

He and his buddies entertained themselves by constructing various kinds of vehicles, including an airplane. Milliken’s academic performance at the neighboring University of Maine. [00:16:00] Persuaded his parents to find money for two years at MIT, where he in 1934, earned a degree in aeronautical engineering and math.

His long life. He lived to 101 was filled with remarkable achievements. His work for Boeing carrying out high altitude test flights led to flight dynamic research at Cornell’s lab in Buffalo. This soon expanded to research with GM on automobile control dynamics and passive safety. Two of his books on race car dynamics and chassis design are considered classic references.

Milliken was an early official at the SECA. With Cornell colleagues, he designed the Glenn’s first permanent track and he served as chief steward at the Grand Prix races competing in more than 100 road races. Included campaigning a 1932 four-wheel drive Miller at Pikes Peak. Carl Luson named him Mr.

Supernatural. Cameron Azinger was born in 1921 in Youngstown, Ohio. His [00:17:00] father, James Cameron, or jc, the first became general counsel and vice president of the Steel Company, Youngstown Sheet and Tube. He was born and raised near Watkins Glen where his parents had established a farm in the late 19th century.

Cameron was the only child of wealthy civically engaged parents, both of whom graduated from Cornell, where his father also attended law school. JC collected cars and own a number of packers. He taught Cameron at age 12 to drive the country roads around the glen, where they had a summer place on the lake.

Shortly before his 20th birthday, Cameron became co-owner of a Youngstown area Packer dealership, which closed a couple of years later when he and his partner were drafted. What is now Youngstown State University grew out of a 19th century YMCA school. In the thirties and forties, it became Youngstown College and severed.

Its YMCA roots. It was very local, a commuter school, financially supported by the [00:18:00] president of Youngstown Sheet and Tube among others, and prominent people were members of its board, including JC Argetsinger. It was the logical place for Cameron to attend after the war when he was married with children.

If he hoped to become a lawyer like his father, Youngstown College would’ve given him the necessary undergraduate degree without complicating his life or perhaps taxing his mind. Cameron’s dream of racing on the streets and roads of Watkins Glen began about the time of his graduation. He would spread magazines on the living room floor to explore different possible circuits.

Maybe with thoughts of the Targa Florio and the Vanderbilt Cup swirling in his mind. Cars were a lifelong infatuation and Cameron’s daily drivers were Packards and Cadillacs. He also owned an MGTC, an Aller J two a Bugatti Type 35, a Healy Silverstone, and a Mercedes 300 SL. In 1970, when the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Corporation rejected by one vote, his offer to buy the circuit.[00:19:00]

Cameron resigned as Executive director. A post he’d held since 1955 replaced by Malcolm Curry, who had been press officer. Argo Singer, soon left the corporation. His son, Michael, writes that Henry Valent pressured the board to vote against the proposal. Vol also falsely claimed that the race might be removed from Watkins Glen.

During the late twenties, the Grand Prix Corporation embarked on projects to improve the track. These included a 4,000 seat grandstand, expanding the pit lane facilities, and enlarging the Kendall Tech Center. After the vote to retain nonprofit ownership, still more was done to modernize the track at very great expense.

The circuit was lengthened by a mile and widened, and two new buildings were constructed. About seven miles of armco. Barriers were built close to the circuit. This design later contributed to two driver deaths in 73 and 74. The GP driver’s Association demanded the barriers be moved back from the circuit, but [00:20:00] the improvement project had already been funded by a $3.5 million bond, plus the expense of another million dollars.

Today, these figures would total a debt of $36 million. What was probably an early, slightly desperate sign of financial problems along with unpaid bills took place in July of 1973 when the track was rented for a weekend rock concert. Summer Jam. Featuring big names like the band sold 125,000 advanced tickets.

Eventually, attendance doubled the size of Woodstock to 600,000. Traffic was backed up for scores of miles and services were overwhelmed. Afterward, local people filed more than 20 lawsuits against the corporation. It’s felt that summer jam damaged the collaborative spirit between track and village.

During this time, Bernie Ecclestone’s, formula One Constructors Association flexed its muscle against the FIA over regulatory and commercial issues and prize money awarded by organizers. It was a tumultuous time in [00:21:00] the sport that put additional unprecedented pressure on Watkins Glenn. After he won the final F1 race at the Glen Alan Jones, who was also that year’s champion, said quote, sure the Glen is a nice scenic track, but that doesn’t mean we should have to live in the Stone Age.

Henry Valent admitted that the race failed to break even during its last four years. Two accountants separately reviewed finances and both concluded that conventional accounting practices had not been followed. This led Cameron Ainger to remark quote, why no one has blown the whistle on this business Is hard to say.

Adding that in his last year of the corporation, the race earned a hundred thousand dollars profit. Reflecting on the situation, I’m inclined to sum it up by employing two metaphors that I used last year. For sporting gentlemen, the Grand Prix was like a traveling circus. It came from far away places once a year bringing exotic entertainment and displaying advanced technologies.

Often seen. For the first time, there was danger [00:22:00] in the activities, which were often death defying. Its visit was briefed but exhilarating. It had no local link except to the fairgrounds it paid to use, and for the circus. This was just another stop in a season of travel facilitated by local organizers.

For villagers, the Grand Prix may have been more akin to a county fair, which is supremely local except for the visiting amusement rides. The fair is all about displays of local good natured competition, fruit and vegetable canning, tractor poles, livestock breeding, and nostalgic objects like old time farm implements.

The long local history of the fair itself is proudly evident at every turn in posters, signage, and activities. Generations of local families participate. But a circus is not a county fair, nor is a fair a circus expecting one to be the other is bound to provoke, clash. The loss of the Grand Prix and the bankruptcy of the track had negative consequences for individuals on both sides of the local issue.

Henry Valent and Malcolm [00:23:00] Curry raised money by mortgaging their houses. Valent died barely a year after the track was sold at 67. Curry was younger, but he too lived only to 67. After he left the corporation in 1970, Cameron went to work for Jim Hall on a project with gm. He then served as SCCA Director of Professional racing and its executive director.

But in 1977, at age 56, he returned to Watkins Glenn to open a law practice. He died 31 years later. Argo Singer’s full-time auto racing employment after leaving the track was brief and he came home just in time to witness the corporation begin its grim, slide into oblivion. He must have felt a deep sense of frustration and disappointment.

It’s hard to imagine that being a small town attorney afforded inger the same satisfaction as running F1 races. Michael Ettinger reports that near the end of Cameron’s life, a journalist asked if he regretted that NASCAR had replaced F1 [00:24:00] nascar. By the way, first raced here in 1977. Well, true enough, but pretty bloodless and maybe masking the passionate feelings of a sporting gentleman.

Racers like Cameron and Volunteer Villagers would surely agree that the unique reward of hosting Formula One transcended mere commercial activity from the mid seventies and after F one’s departure from the Glen until 2017 when Liberty Media bought the sport. The US Grand Prix raced at seven Tracks.

All but Indianapolis and Austin were temporary and they hosted the race from one to eight years, four times. There were four US Grand Prix in a single season, only at Coda, a new $300 million permanent track. Did the race finally find something like a. One reading of this is to say that it was chaotic and reveals an uneven, maybe declining US.

Interest in Formula One, NASCAR and American Open Wheel Racing were likely more popular then with network TV coverage and Fortune 500 sponsorship. [00:25:00] You could almost say there was US Grand Prix racing before and after Watkins Glenn, with neither comparing favorably with the Glenn years until very recently.

This raises the intriguing question, what if Cameron Argetsinger had bought the track? There were public perplexity and disgruntlement when the race was lost. Lenz and Curry’s lives and maybe reputations were damaged. Cameron and Argo Singer’s full-time involvement in motor sports came to an end three decades before his death.

None of these things might have occurred. The next years of Formula One transformed the sport, especially technologically with respect to engines, aerodynamics and safety TV coverage in the US was sporadic, but in retrospect, F1 was maturing alongside new media like cable television that soon brought about the mediatization of sports generally.

Finally, formula One became a globe spanning business, so. Could a successful USGP have influenced these changes and [00:26:00] made the sport more attractive to North Americans. If the USGP took place at multiple venues, there are now three. Could Watkins Glen have been their owner or partner? Might this have given the Glen a seat at the table or offered at a role in sanctioning when Liberty bought the sport?

And conversely, would Watkins Glen International be a different enterprise? Most of all, less dependent on NASCAR for big crowds and financing. And finally, in 1974, Cameron Argetsinger proposed a US Grand Prix race through Central Park in New York City. Think about that if only Thank you.

Kip Zeiter: Thanks, Jim. That was fascinating. I always liked Alan Jones until I heard that comment. Uh, stone Age. Come on. Uh, does anyone have any questions for Jim?

Joe Schill: I have a question about the relationship between Mr. Valent and Mr. Argetsinger. [00:27:00] Was there a history of bad blood there, or why was he so opposed to Cameron Argetsinger purchase offer?

Jim Miller: So there’s a great deal of speculation in this kind of analysis. It’s difficult to find records, for example, where are the minutes to the corporation meetings where you might have seen a disagreement? One could say from what is on the record and even some of what I proclaim today, Valent was a very local guy who did very well for himself and probably had strong connections in the community.

Different from Cameron, who arguably des descends from a family who had spent more than a century here, but was a kind of outsider and a and a privileged guy. And there may have been something at the very, very personal level that had nothing to do with. And I guess I would wanna say that if any of that is the case, I, I wanna try to locate, locate it in this idea of, of a sporting gentleman, which I would say Cameron Arge Singer, the guys who initially set up road racing, uh, shared, and then someone like vit, smart, educated, but very local in, in a different way.

[00:28:00] There’s also probably a danger and over personalizing this kind of thing.

Niger Hale: No, I just wanted to clarify the two quotes that you attributed to Len. In 11 years, he switched his point of view from private being bad to private being good. That’s what you put up there, right? I think

Jim Miller: I’d rather just let this, those quotes stand alone.

I mean, I, it was remarkable to see that whatever was going on, I mean, he just may have been very frustrated and angry at the end. Full stop.

Audience Q&A: As far as you know, have there been any clashes between sporting gentlemen and local places elsewhere, or is this a uniquely Watkins Glen phenomenon?

Jim Miller: Well, what I might pursue next is something called the Watkins Glen Effect, where there’s a claim that.

In the fifties when road racing came to America and tracks like the three I mentioned, bridge, Hampton and Lime Rock and so forth. They were sort of part of a larger phenomenon that the Glen had led the way and there was a kind of imitation and cross fertilization. Now, would that mean there was [00:29:00] a tension?

Well, bridge had doesn’t exist anymore, and a lot of that is due to people hitting the noise and what have you. You can’t race on Sundays at Lime Rock. So maybe this happened, but it wasn’t fatal, and maybe that’s the case because the stakes weren’t as high as Formula One racing. That’s an intriguing question because if you claim to be doing a a case study, well then a what and how about some other examples

Alana Roberts: to the previous gentleman’s point, I think Las Vegas was actually a great example of that, where at one point they blocked the view of the course for the walkway.

So you’re seeing sort of an urbanization where you’re still creating a, an us and them. And so I guess my question would be with the major circuits being in major cities, how are we transitioning from this? Small town, us and them to big city, us and them.

Jim Miller: I think what I’m trying to describe was a different era.

Post Liberty Formula One is something entirely different. It’s a media spectacle and these cities are knocking Liberty’s doors down to have this opportunity [00:30:00] for attention and moneymaking and, and most of all, celebrity presence. So it’s sort of an apples and oranges comparison and maybe last year’s. Las Vegas race was kind of teething problems as they figured out how to organize things.

The best. The more interesting question about Vegas is that there was one years ago through a parking lot, I’m forgetting the author’s name, but it, it was heavily inflicted with or assisted by the mafia. You know, so that would be more interesting Vegas then and now. Yeah.

Audience Q&A: You had brought up the possibility of proper accounting methods weren’t used in those final years.

How did that play out in the town when, I have to think that just brought in suspicion of theft and questionable use of, of proceeds and monies.

Jim Miller: I think, again, there’s a problem with lack of records and when I’ve talked with people, they would say things like, well. Sale of tickets was always pretty casual.

There was even someone suggested there might have been phony tickets, you know, produced [00:31:00] and sold. I think in a, in a way, maybe some of this has to do with a conception of this whole enterprise. It’s just a bunch of friends who get together and do things that are good for the local people. And was there criminal activity?

I don’t know. The lack of records is really a, a difficult hurdle. And maybe in the end it doesn’t matter. ’cause the effect would, would be the same. Would anyone like to challenge the sort of argument that I’ve laid out?

Joe Schill: Okay. I’m not gonna challenge, but as the new archivist at the International Motor Racing Research Center, we’re gonna get you those records.

That’s, that’s a promise.

Jim Miller: It sounds like you’ve just arrived the other day, right? Dusty boxes of. Okay.

Kip Zeiter: I’m old enough. I was at one of the original Las Vegas gr pri in the, uh, parking lot. Did somebody else have a question? Did I step on somebody else there?

Lyn St. James: I just had a comment. Oh, I’m sorry. Yes. Lynn, I’m gonna challenge you Good when I make my presentation.

Oh, good. Good.

Kip Zeiter: Ooh, [00:32:00] stick around for that.

Jim Miller: Yeah, I was actually going out for lunch during that time. Uh, I just wanna say that that’s the nature of this kind of work. None of us claims to have the truth, you know, it’s a conversation that doesn’t stop. So thank you. I, I would be honored.

Kip Zeiter: All I can say is somebody old enough to have attended a lot of those Grand Prix up on here.

It was just a magnificent time of year. We geared up for it. It was great. Vegas, the first Caesars Palace Grand Prix was really corny and fake and ridiculous. I was at Long Beach when they were still running Grand Prix cars, and that was pretty cool. I liked Mosport a lot too, but this was still not to sound like the old guy telling people to get off my grass.

This is really the rightful home of the US Grand Prix, and that was a fascinating presentation, Jim. So thank you again very much.

Jim Miller: Well, I can’t, since you’ve mentioned old guys getting nostalgic, I can’t resist the reference to weather everything you read about the Glen, you know it’s in the fall and the leaves are turning.

I came here one year and it’s snow. Thank.[00:33:00]

IMRRC/SAH Promo: This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motor sports. Spanning Continents, eras, and race series. The Center’s collection embodies the speed, drama and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers. Race series and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the center, visit www.racing archives.org.

This episode is also brought to you by the Society of Automotive [00:34:00] Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers, organizational records, print ephemera, and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www.auto history.org.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports.

And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization [00:35:00] through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 The Golden Era of Formula One at Watkins Glen

- 01:33 The Rise and Fall of Watkins Glen

- 02:03 The Community Behind the Races

- 03:36 Sporting Gentlemen vs. Small Town Residents

- 06:01 The American Small Town Identity

- 11:01 Key Figures in Watkins Glen Racing

- 19:21 The Financial Struggles and Final Years

- 21:41 Reflections and What-Ifs

- 26:51 Q&A Session; Closing Remarks and Credits

Livestream

Learn More

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

If you enjoyed this History of Motorsports Series episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:Consider becoming a Patreon VIP and get behind the scenes content and schwag from the Motoring Podcast Network

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

The Glen’s first F1 race in 1961 was a scramble – approved just six weeks before the October date. Yet it became the longest-running U.S. Grand Prix venue, voted best-organized race three times by drivers. The secret? A deep collaboration between organizers and villagers.

But by 1981, the dream unraveled. Financial woes, unpaid prize money, and mounting debt led to the race’s removal from the calendar and the track’s bankruptcy auction. Miller suggests the split began in 1969, when Cameron Argetsinger – founder of the original street race and a quintessential sporting gentleman – offered to buy the track. His proposal was rejected, and he resigned. The rift between cosmopolitan racers and local stakeholders had begun. Miller profiles five key figures who embodied the Glen’s small-town ethos:

- Donald Brubaker, Penn Law grad turned organic lodge owner, hosted F1 teams and led the Chamber of Commerce.

- Malcolm Curry, newspaper publisher and later Grand Prix executive director.

- Henry Valent, Cornell-educated lawyer, radio station co-owner, and civic leader.

- Liston Kuhn, rural-born judge and Air Force reservist.

- Joe Franz, Italian-American innkeeper who taught F1 drivers golf and helped build the local course.

These men weren’t racers, but they were the backbone of the Glen’s motorsports miracle. Miller contrasts them with three “sporting gentlemen”:

- Frank Griswold Jr., Harvard legacy and social register aristocrat, winner of the Glen’s first race.

- William Milliken Jr., MIT-trained aeronautical engineer and racing innovator.

- Cameron Argetsinger, Packard dealer, Cornell legacy, and visionary behind the Glen’s racing rise.

Their world was one of country clubs, European cars, and elite camaraderie. Their vision for racing clashed with the Glen’s grassroots stewardship.

After Argetsinger’s departure, the Grand Prix Corporation undertook costly upgrades – grandstands, barriers, buildings – funded by millions in bonds. Safety issues arose, lawsuits followed a chaotic rock concert, and Formula One’s globalizing pressures mounted. Bernie Ecclestone’s FOCA demanded more money and professionalism. Watkins Glen couldn’t keep up.

Alan Jones, 1980 champion, dismissed the Glen as “Stone Age.” The race failed to break even for four years. Two accountants found irregularities. Argetsinger lamented the lack of oversight. The circus had outgrown the county fair.

What Might Have Been

The fallout was personal. Valent and Curry mortgaged their homes. Valent died a year after the track’s sale. Curry passed at 67. Argetsinger returned to law, his racing career cut short. Argo Singer came home to watch the decline unfold.

Miller’s metaphors are poignant: to the sporting gentlemen, F1 was a traveling circus – exotic, thrilling, transient. To the villagers, it was a county fair – local, generational, deeply personal. Expecting one to be the other was a recipe for heartbreak.

Miller ends with counterfactuals: What if Argetsinger had bought the track? Could Watkins Glen have shaped F1’s American future? Might it have become a permanent fixture in a sport that wandered from venue to venue for decades?

Today, Formula One thrives in media-saturated cities like Austin, Miami, and Las Vegas. But the Glen remains a symbol of what happens when passion meets place – and when collaboration is both the engine and the Achilles’ heel of motorsports history.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies. The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)