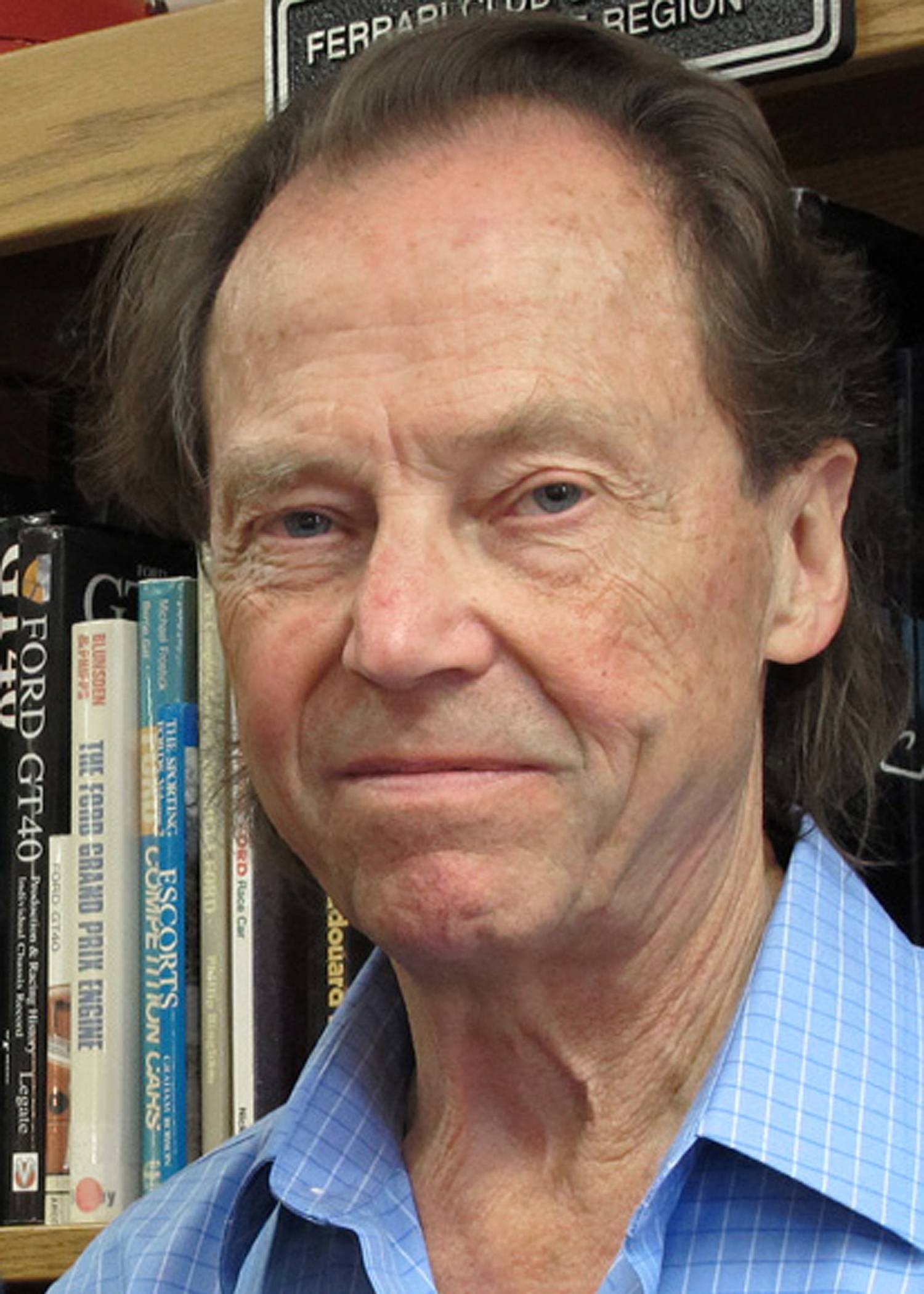

Skip McGoun has presented and published on the history and culture of finance as well as automobile history and culture and served as area chair of the Vehicle Culture Section of the Popular Culture Association. He considers the two senses of the word “Sports” – competition & recreation – and their relative roles in the creation of the class of vehicles known as “sports cars.”

Bio

Elton G. “Skip” McGoun is an emeritus professor of finance at Bucknell University and a visiting professor at the University of Ljublijana in Slovenia and at the University of Donja Gorija in Montenegro.

Notes

Transcript

[00:00:00] Break/Fix’s History of Motorsports series is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center, as well as the Society of Automotive Historians, the Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argettsinger family. Putting the sports in sports cars by Elton G. McGowan. Elton Skip McGown is an emeritus professor of finance at Bucknell University and a visiting professor at universities in Slovenia and in Montenegro.

He has presented and published the History and Culture of Finance as well as Automobile History and Culture and served as area chair of the Vehicle Culture section of the Popular Culture Association. He considers the two senses of the word sports. Competition and Recreation and their relative roles in the creation of the class of vehicles known as sports cars.

Alright folks, next up is putting the sports in sports cars by some guy named Elton [00:01:00] McGowan? Oh, you mean Skip. Skip McGowan. Skip McGowan. This is not a formal occasion. Skip. Okay. Well, we heard the term sports car at least a few times this morning. Of course, that’s not so surprising in a venue like this, but it is a term that you hear all the time in all sorts of places.

But the uses don’t always seem to be compatible with each other. In the 15 years following World War Two, There were a whole series of books published on sports cars. In the introduction to each of the books, or in the first chapter, they would provide a definition of what they considered to be a sports car, and then they would go through and list all of the sports cars that had been manufactured up until that point.

Not surprisingly, The definitions differed. The lists differed. And I have to admit, I’ve always been kind of intrigued by the question of just what is a sports car. Now, [00:02:00] for me, the car part was not a problem. Maybe it should have been, but it wasn’t. The problem I had was with the sports part. Now, what I’d like you guys to do is think.

The word sports. What images do you have, what associations do you have, what connotations do you have with that word sports? Some are probably obvious. One is the notion of competition. Sports, competition. I think that might be a little too simplistic. Because when you think of sports, you also think of just recreation.

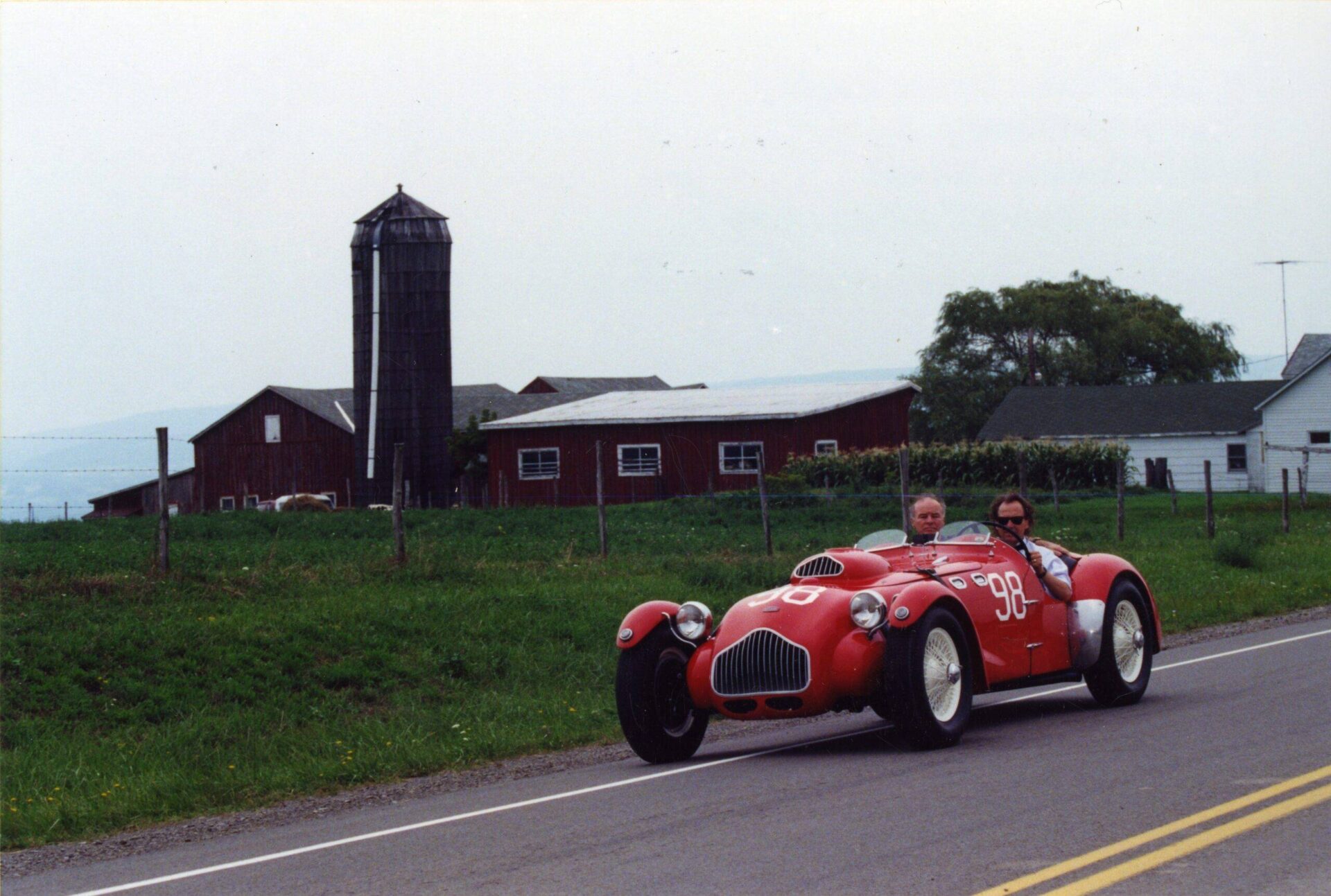

This photo here kind of implies there’s a connection between recreation that we see here and maybe ultimately some sort of competition. But if you think about it, it doesn’t necessarily have to go that way. You don’t necessarily have to start with the competition and then move on to the recreation. You can [00:03:00] start with the recreation and move on to the competition.

After all, there wouldn’t be professional sports of any sort if people didn’t find the subject enjoyable and had an interest in it. There’s another connotation or association of sports that might not pop into your head immediately, but when I show you the image, it should become clear. Sports is a style.

And I put the term sportswear up there because it’s very common. What’s the connection between sportswear, competition, and recreation? I looked at these pictures, which are photos that I got when I googled image for sportswear. And I had kind of a hard time associating that with competition. Now obviously the footwear on at least the two models to the right might have something to do with track and field.

And the model on the right is [00:04:00] wearing something produced by Nike, which we knew at least initially was designing competitive sportswear. Nonetheless, though, even though these associations, the competition, the recreation, the style, in some way go together. But also in some way can be very different with that sort of introduction.

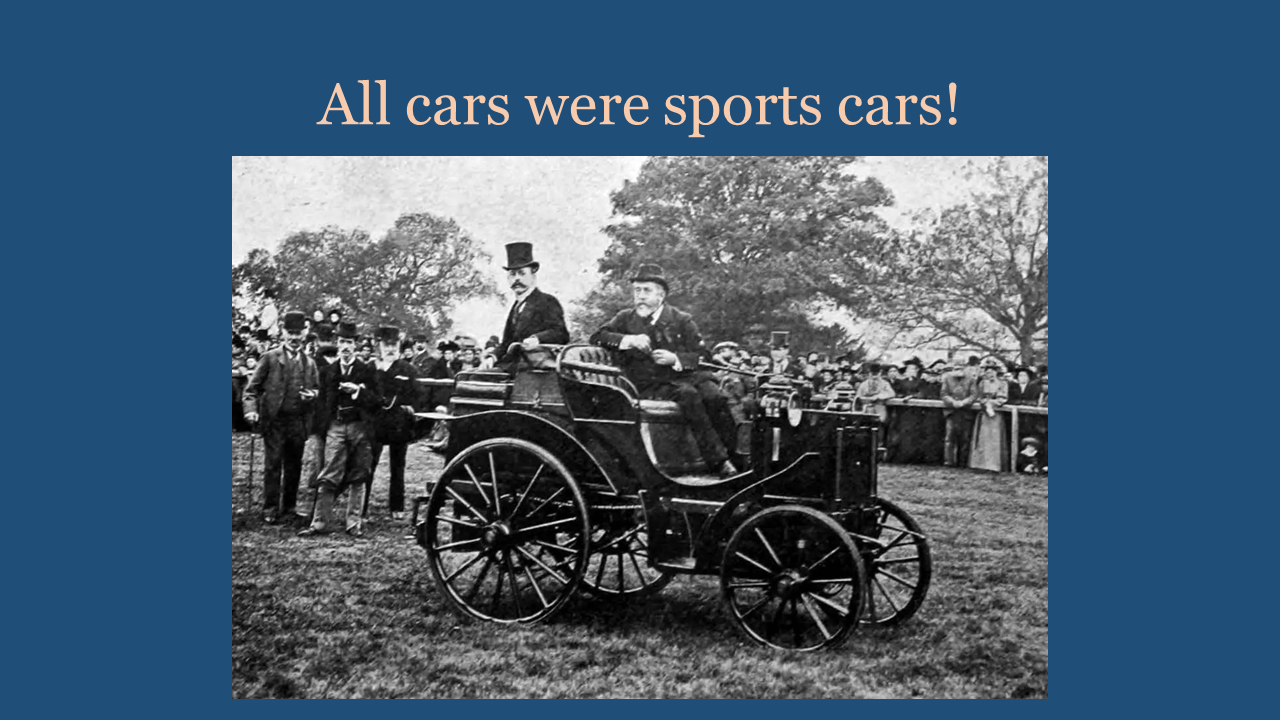

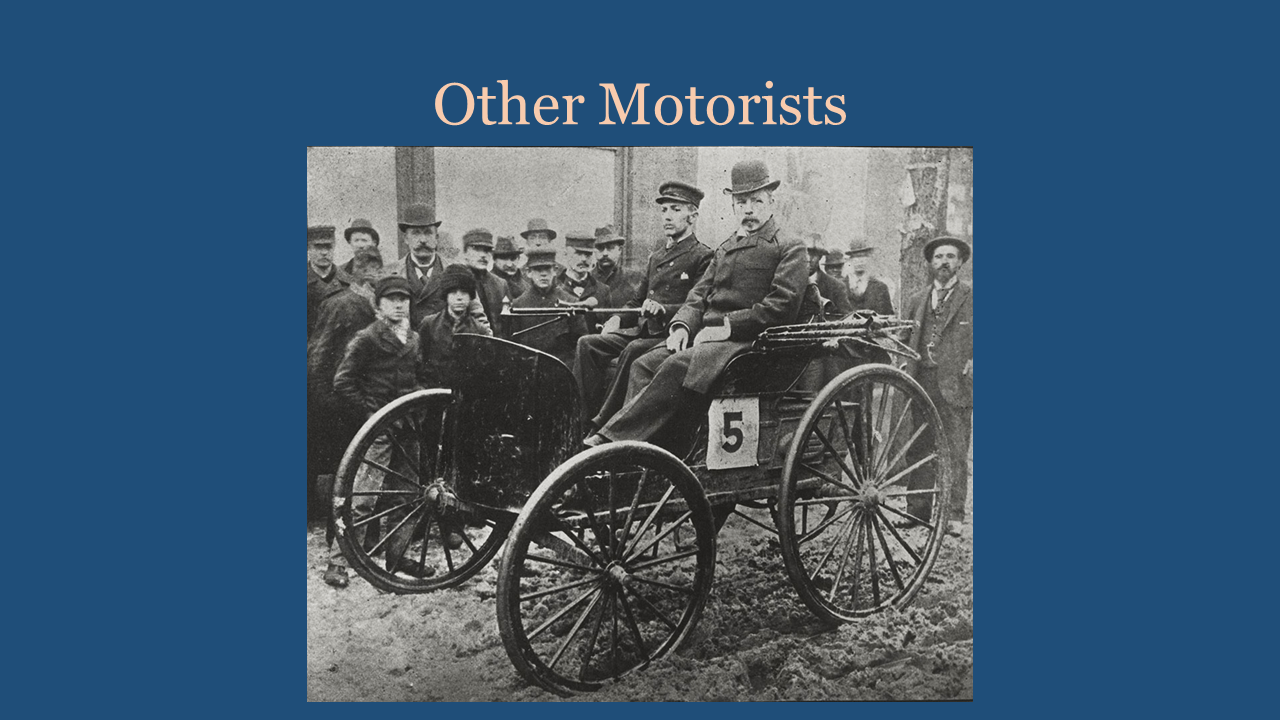

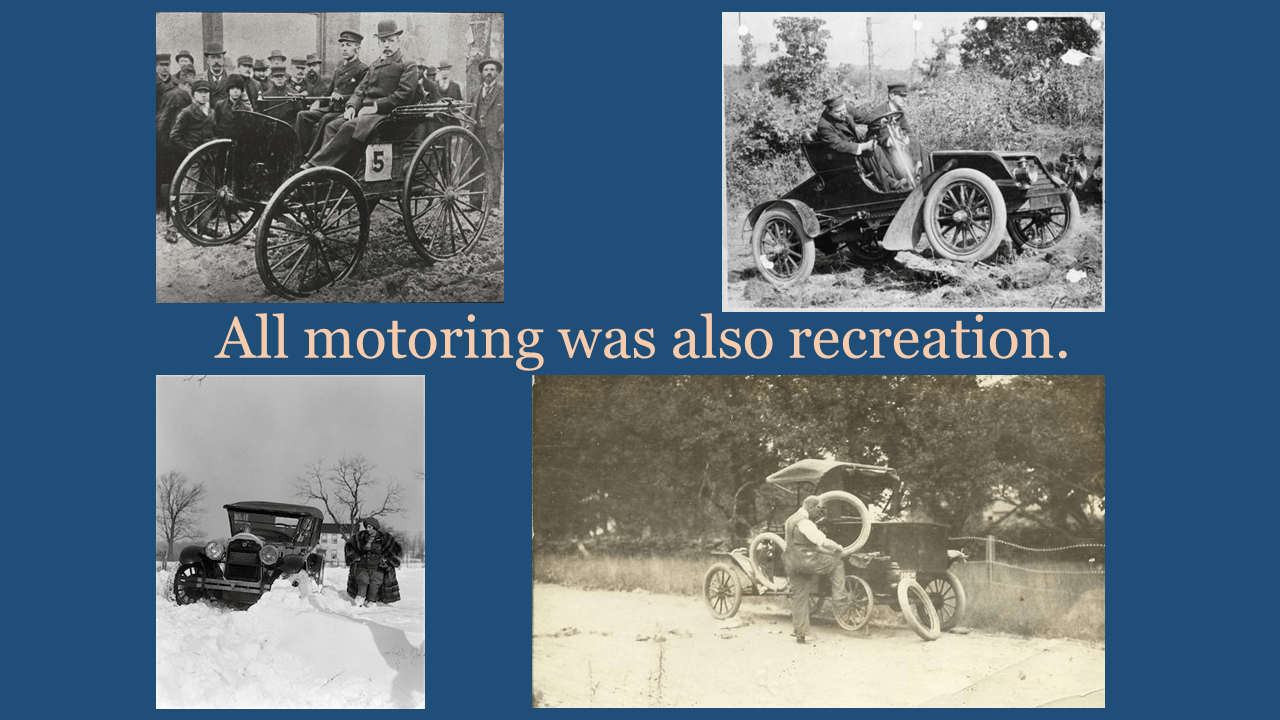

Let’s move on to something a little more closely related to sports cars. I’ve encountered books in which at least a couple of authors had said in the beginning, all cars were sports cars, but what did they mean by that? Well, in one sense, they could have meant that all motoring was competition. The obvious form of competition was.

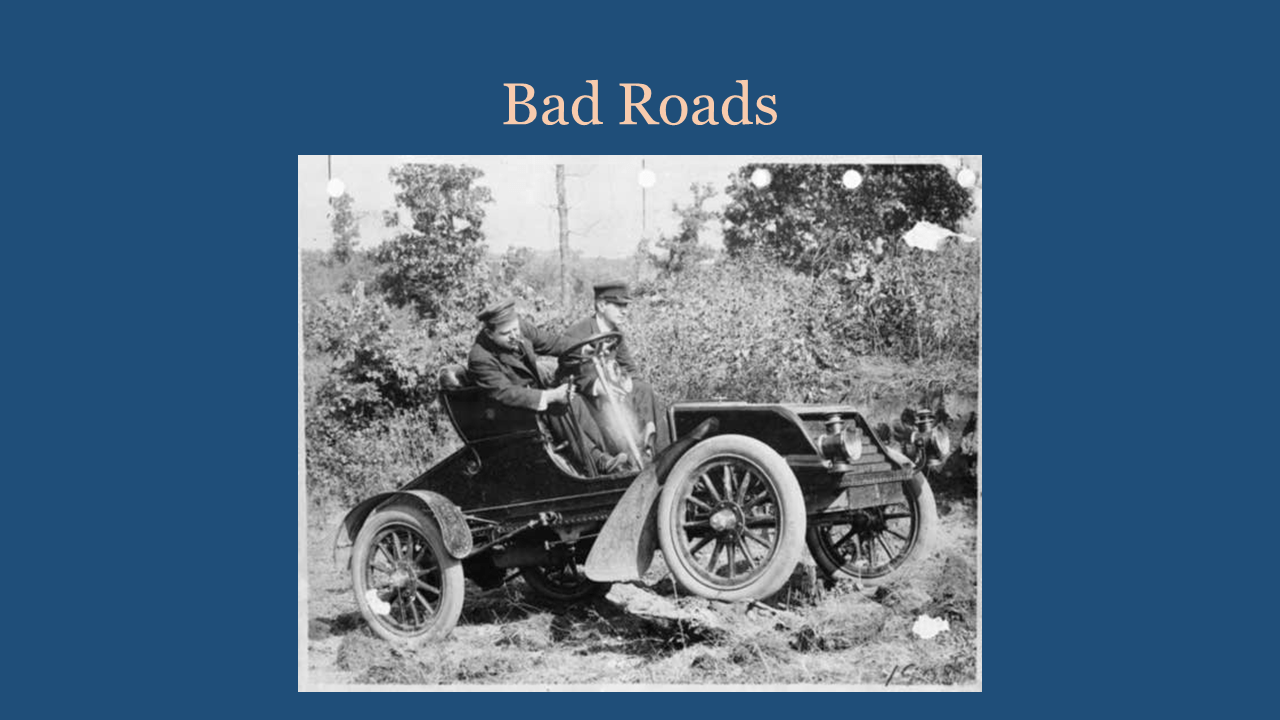

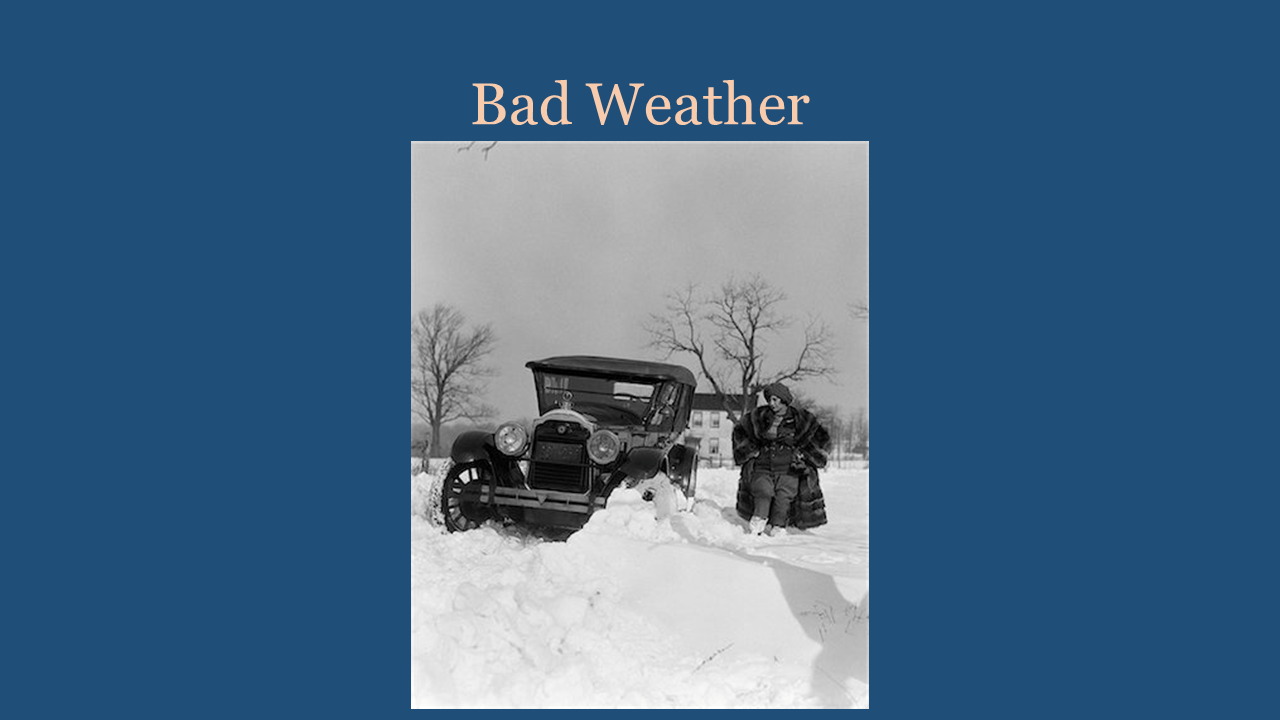

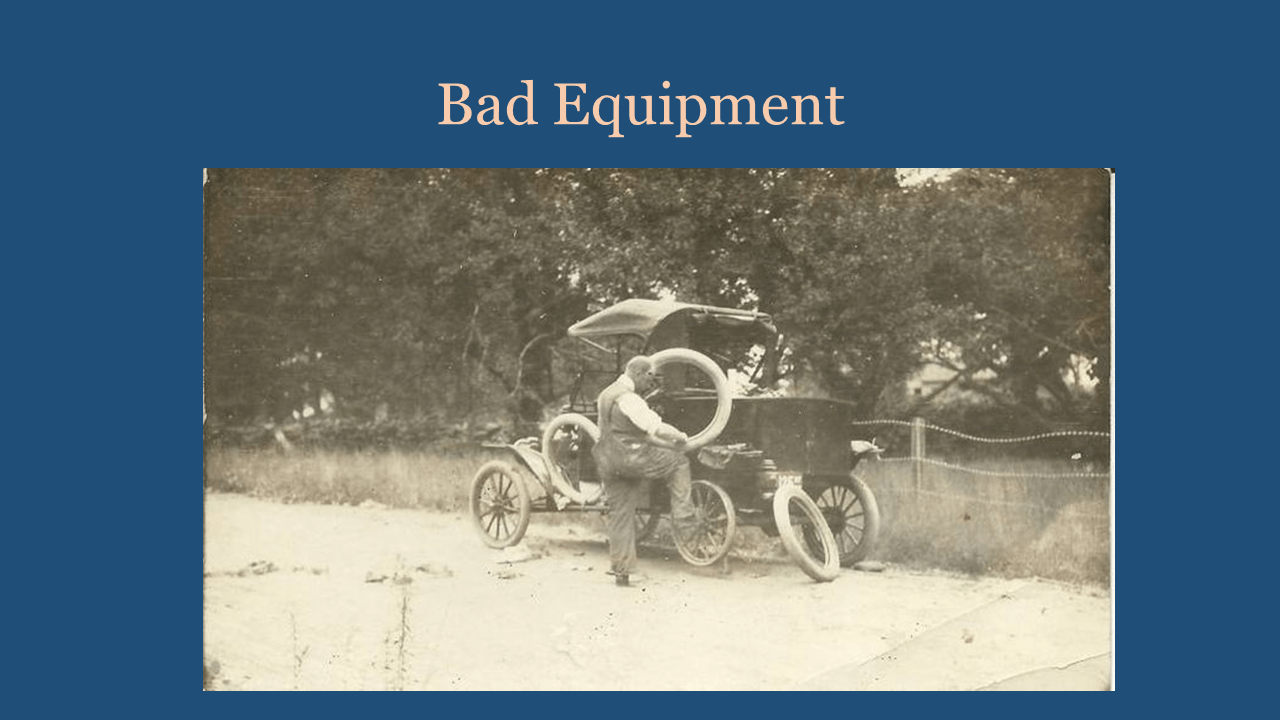

competition with other motorists. You know, in fact, I’ve seen it said that, you know, motor sports developed when the first car met the second car. But keep in mind, there were other forms of competition. Early motorists were [00:05:00] certainly competing with bad roads. They were competing with bad weather. They were definitely competing with bad equipment.

You could certainly say that early motoring Was all competition in one form or another, even if you were out there by yourself, you were competing with something. However, if you look at it a little differently, you could argue that at the time, all motoring was recreation. No one would have been doing this if they didn’t enjoy it.

Sure, technically you could look and say, they were competing. But you also could say that this was a pleasant recreational activity, at least pleasurable in some way. Then motoring evolved. It evolved in two ways I think that are relevant here. One is, automobiles actually became useful. People discovered that these weren’t anything necessarily [00:06:00] frivolous.

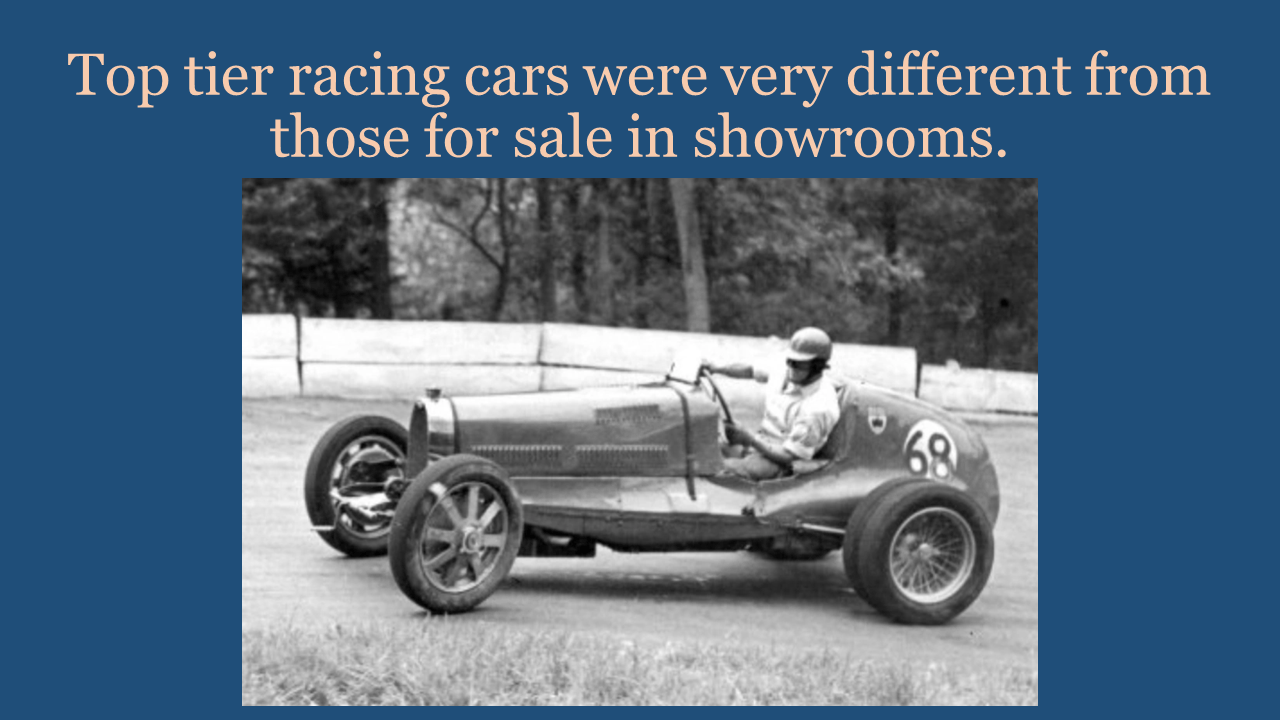

You could actually use an automobile to make your life better. The automobile enabled you to perform necessary tasks much more easily than you ever could before. Another change had occurred around the same time that racing cars became much more specialized. Originally, maybe anyone could get out in their car and compete, but it didn’t take too long before the competition reached such a high level that racing cars were very, very specialized.

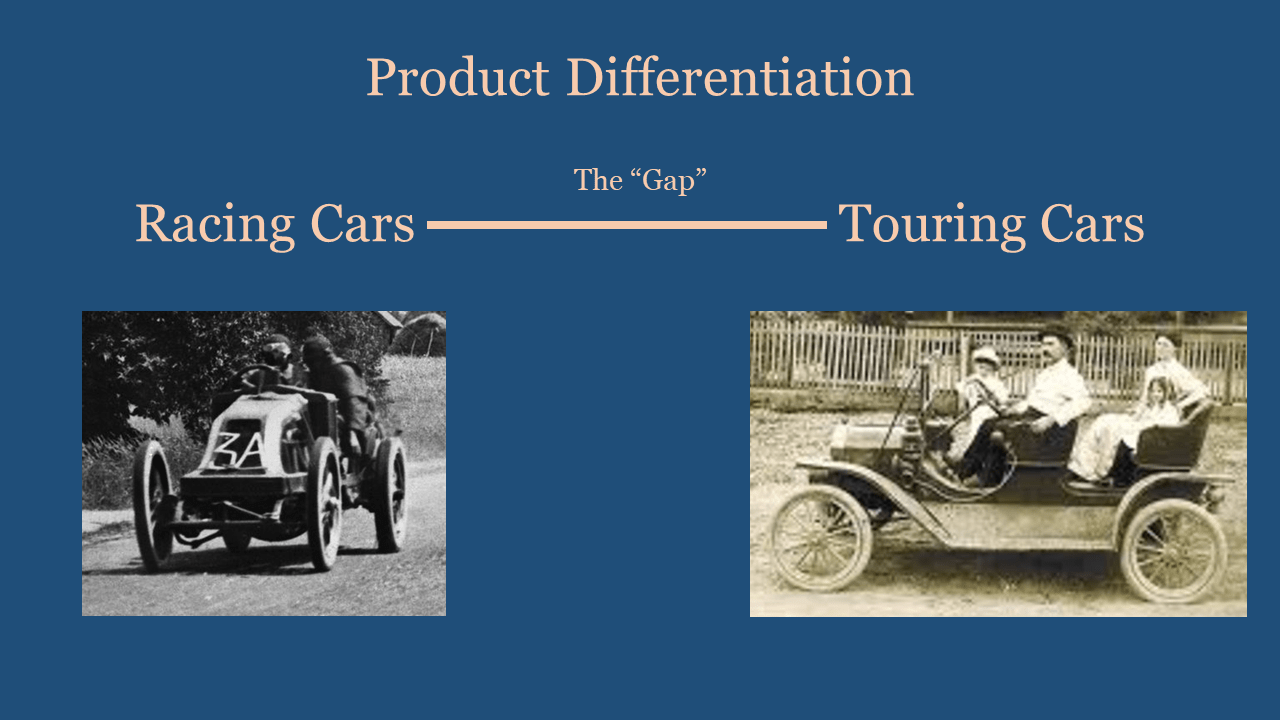

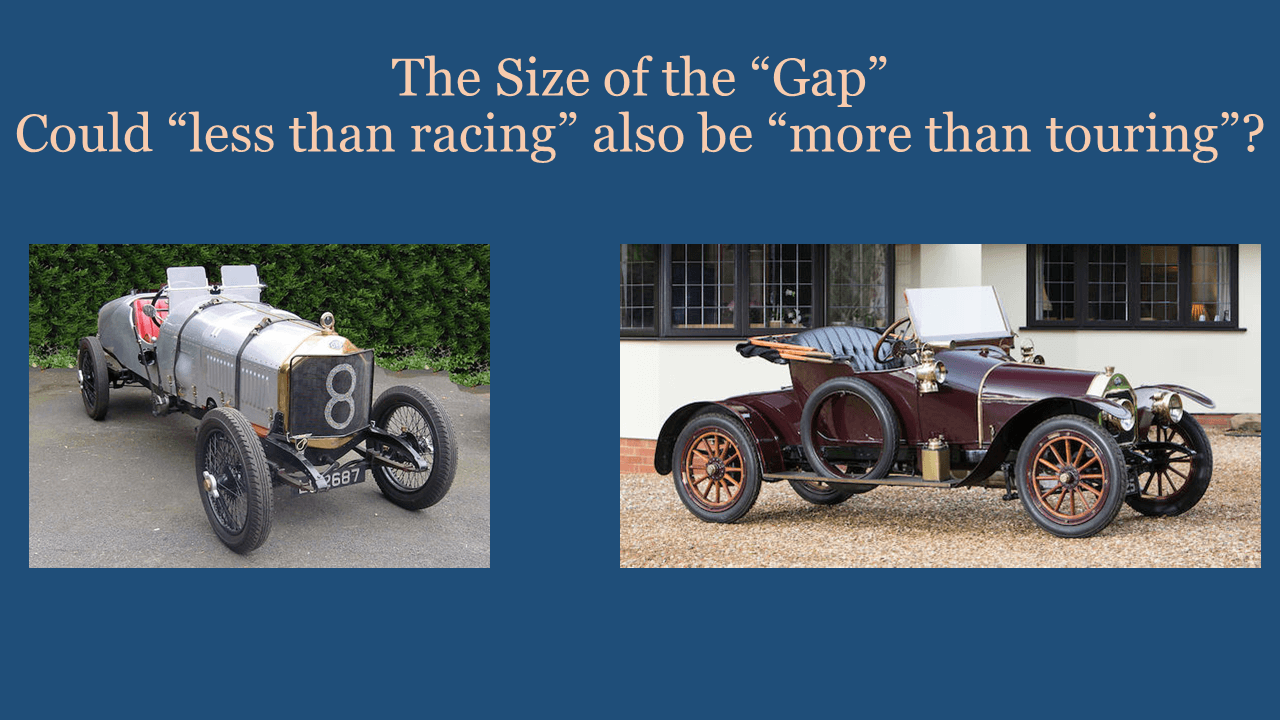

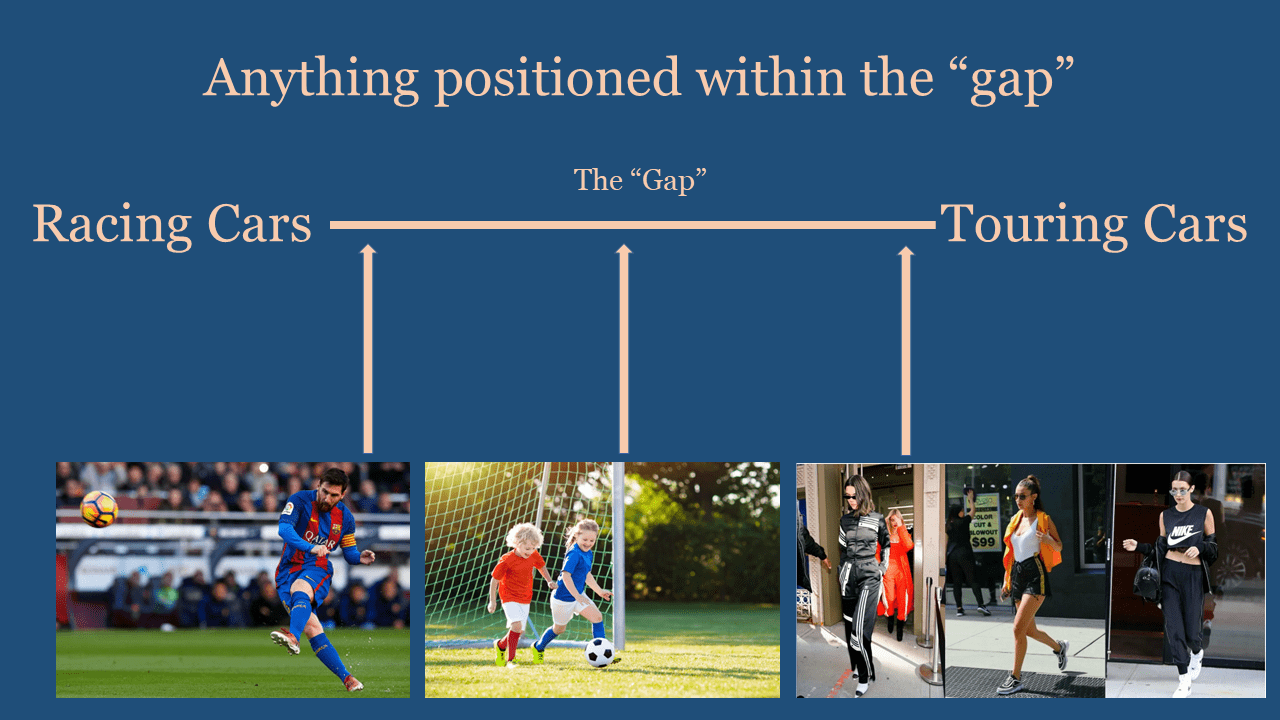

They were very different than the cars that people were using for other purposes. What this meant was we had product differentiation. So on the left, we had racing cars, which were highly specialized for racing. And on the right, we had what at the time were called touring cars. Pretty much touring car meant.

A car [00:07:00] you just use for normal, everyday purposes. Keeping in mind that the word touring does have some kind of recreational connotations to it. So you’ve got racing cars, and you’ve got touring cars. Now obviously this wasn’t an either or proposition. You know, you didn’t have one or the other. You had what I’m calling a gap in between the two, which was certainly filled by vehicles.

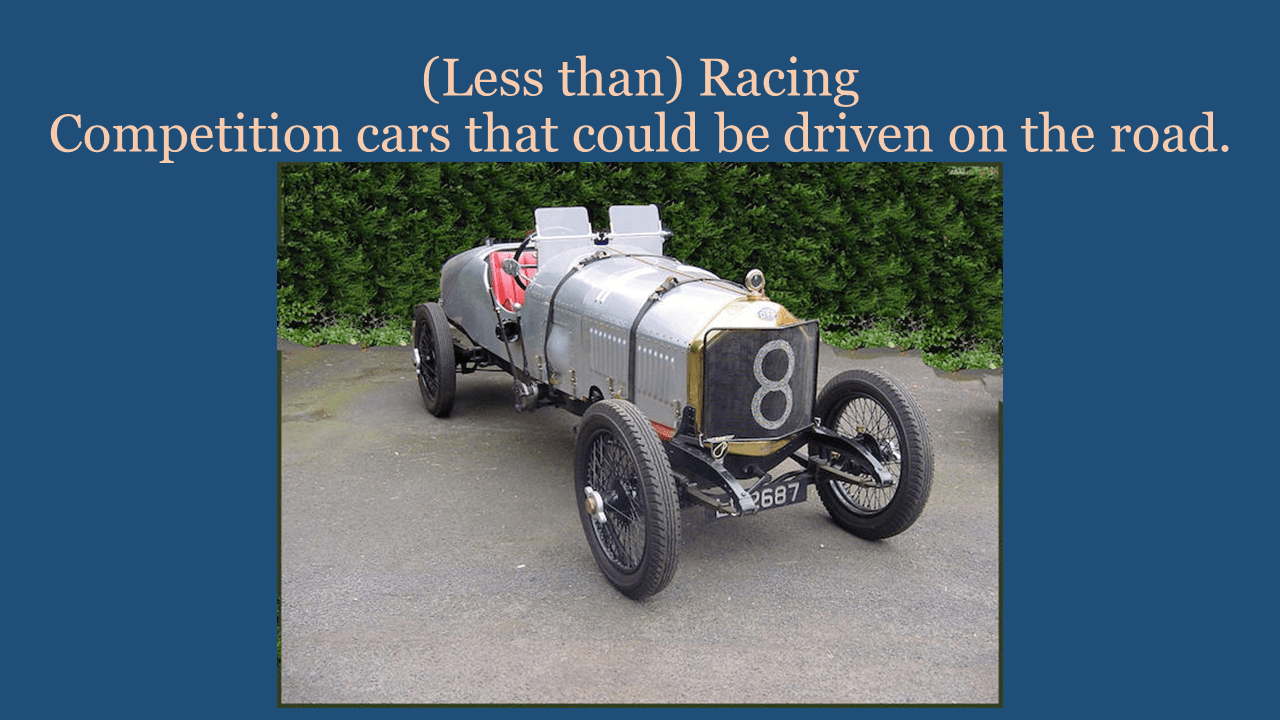

What was in the gap? What I’m calling at one end of the gap might have been a car you could call just a little bit less than racing. It was competitive in certain forms of competition but at the same time it could be driven on the road. You could drive the car to the competition, you could compete creditably and then when it was over you could drive it back home again.

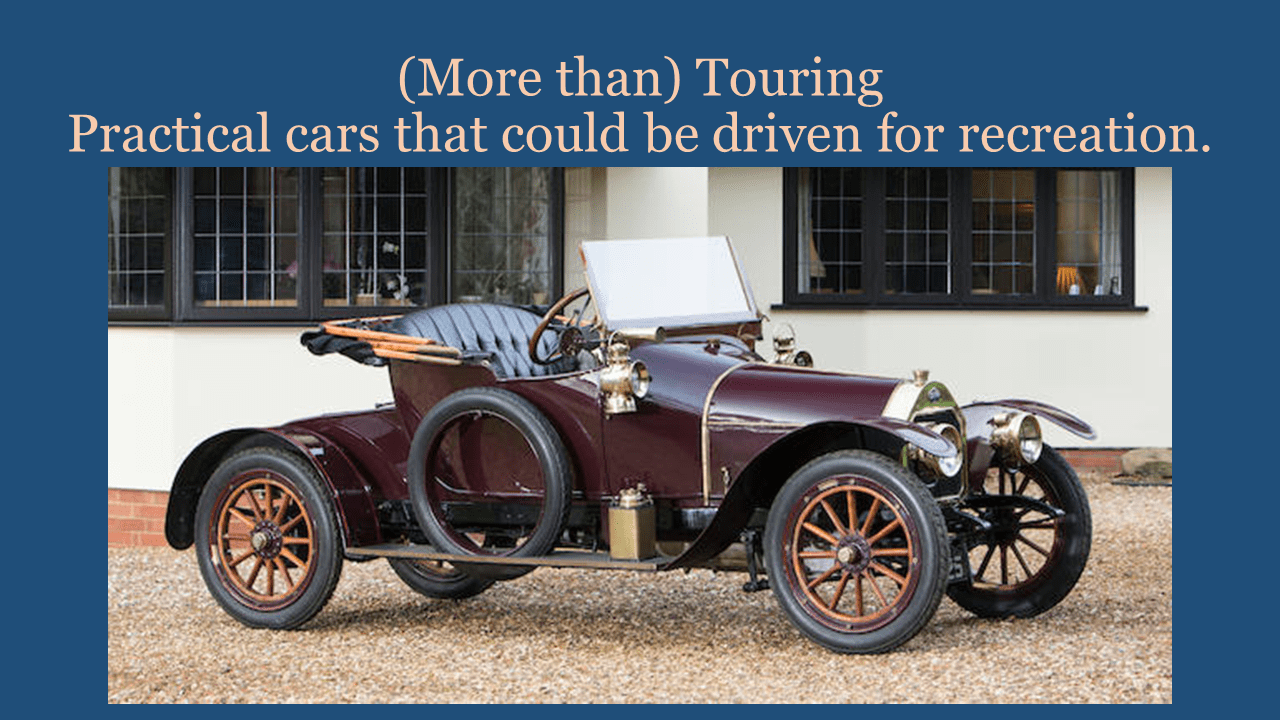

And you might even drive the car someplace during the week. [00:08:00] Okay, so it was a car that was maybe a little bit less than a racing car. It kind of fell into that gap. On the other hand, you had cars that you could say were maybe a little bit more than touring. They were practical cars, but at the same time there was something special about them.

There was something fun about them. They had a little zip, a little pizzazz. Something that kind of stood out from your generic touring car. The question though is, how big is this gap? What sort of range of vehicles do we find within it? Early on, the question I think that you could ask was, could a car that I’ve described as like, a little less than racing, be essentially a car that was just a little more than touring.

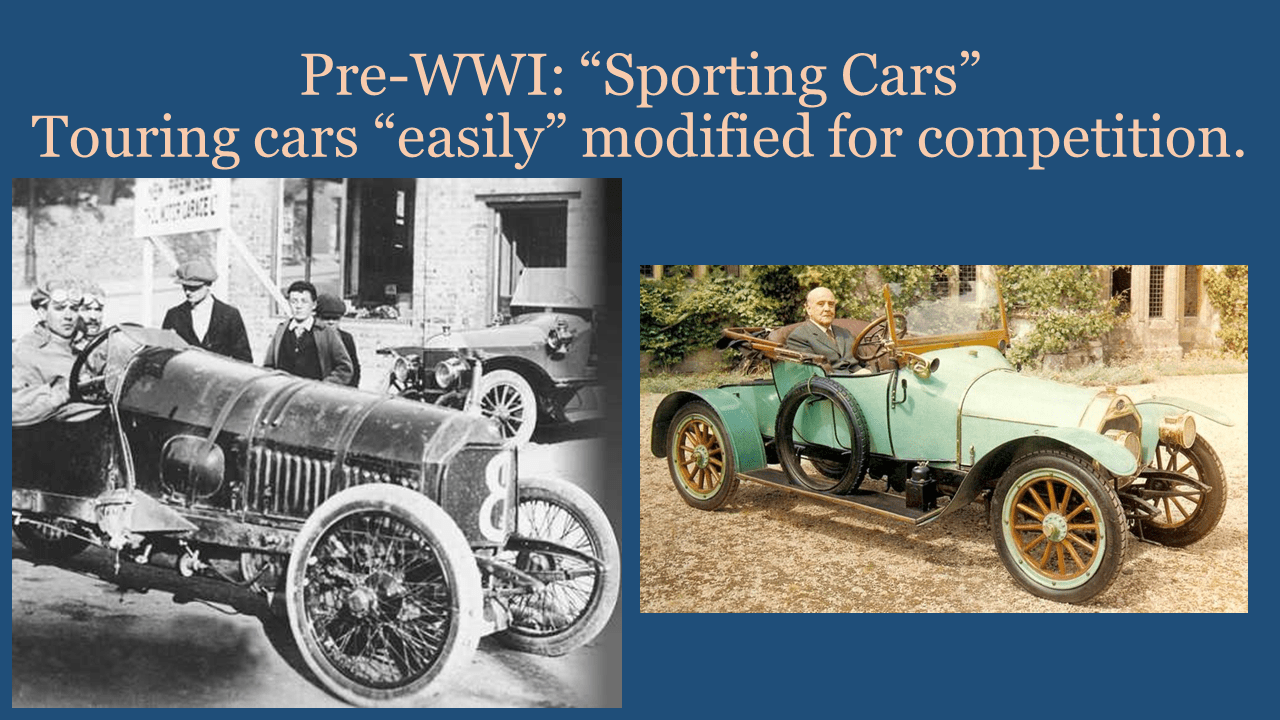

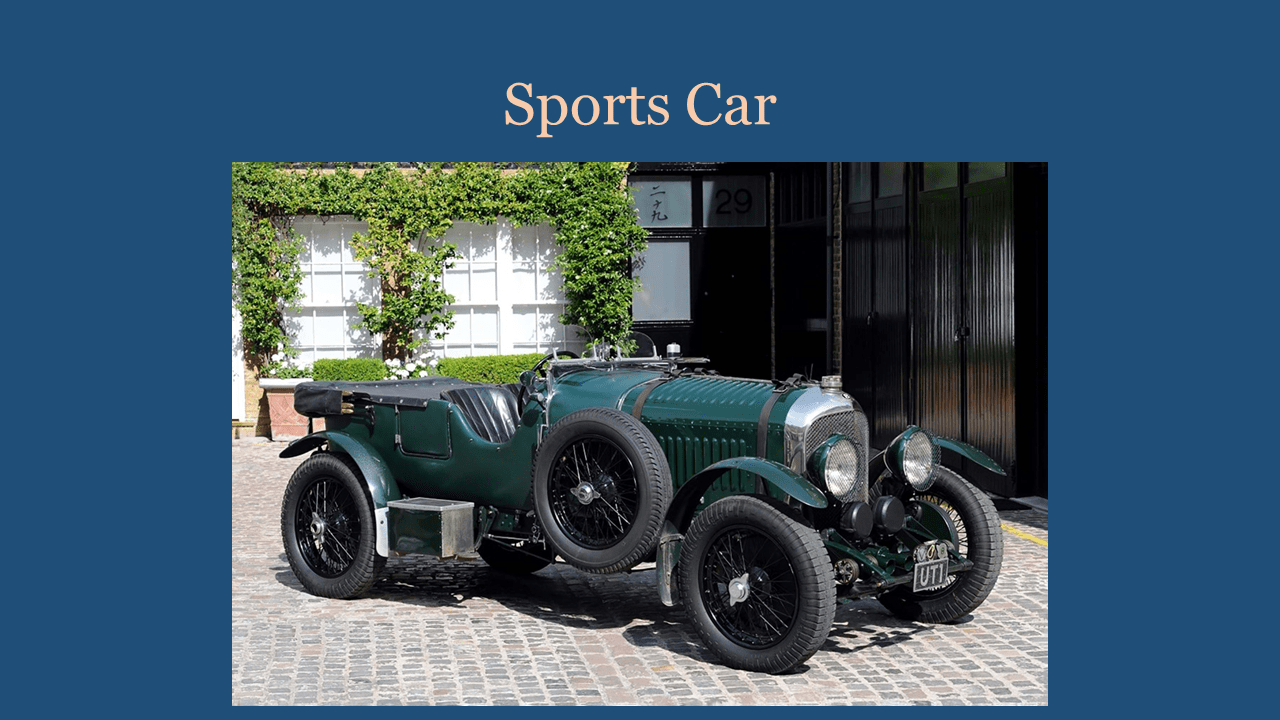

Are we talking really about the same vehicle? And it turns out, we actually could at the time, before World War I. So before [00:09:00] World War I, these cars, in this gap between racing and touring, were referred to as sporting cars. Seriously, I mean, this was the generic term. Sporting cars. You know, this is not a term that I ever think was formally defined, at least nowhere that I could find it.

But the idea was that a sporting car was a touring car that could easily, and notice easily is in quotes, you know, what’s easy for one person could be nearly impossible for another. But these were touring cars that could be easily modified for competition. And the images that I’ve shown there are both W.

O. Bentley. Who was the English distributor for DFP on the right, we see him looking rather sporty himself in one of the vehicles, but on the left we have what I understand is pretty much the same vehicle he was selling in the showroom, but modified for [00:10:00] him to be very competitive in the tourist trophy race pre World War One sporting cars.

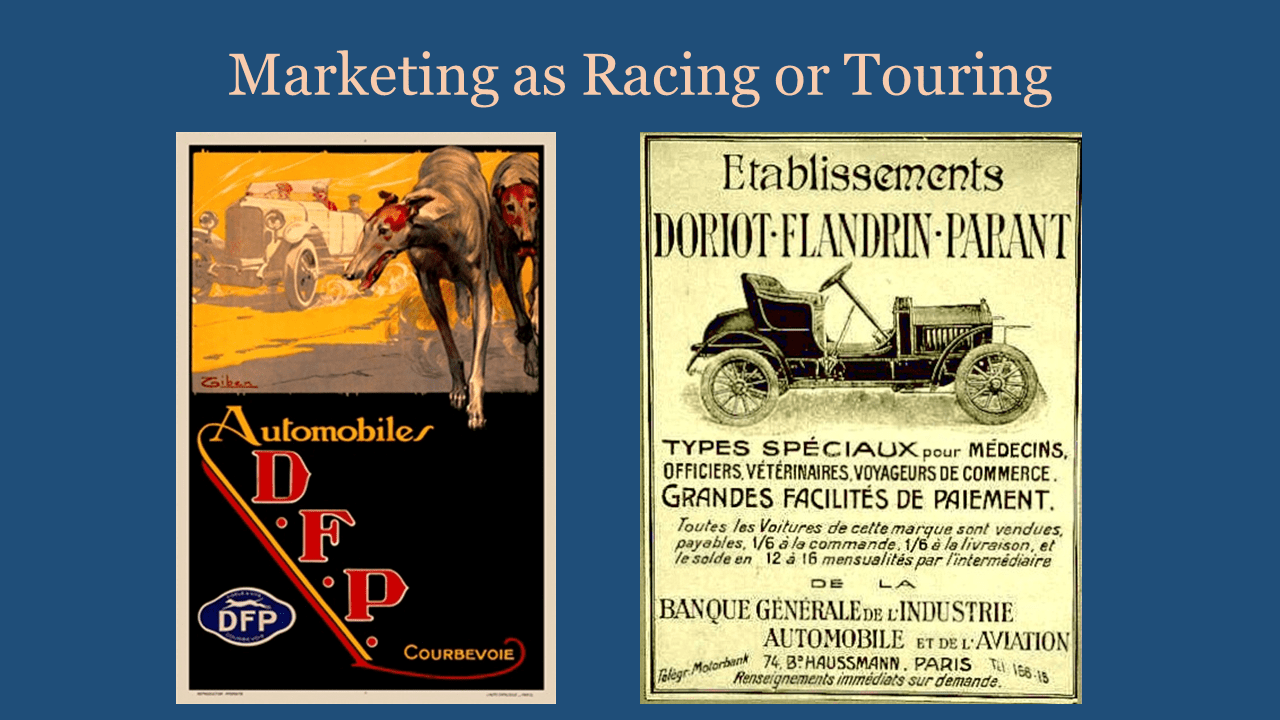

Same car, a little nicer, a little more fun than the regular touring car, but also easily modified to be a competitive car. What this did was it kind of facilitated marketing. Okay, so we have two posters here for the DFP. And you can see that the orientation of the poster on the left was kind of targeting this sort of racing image of the vehicle.

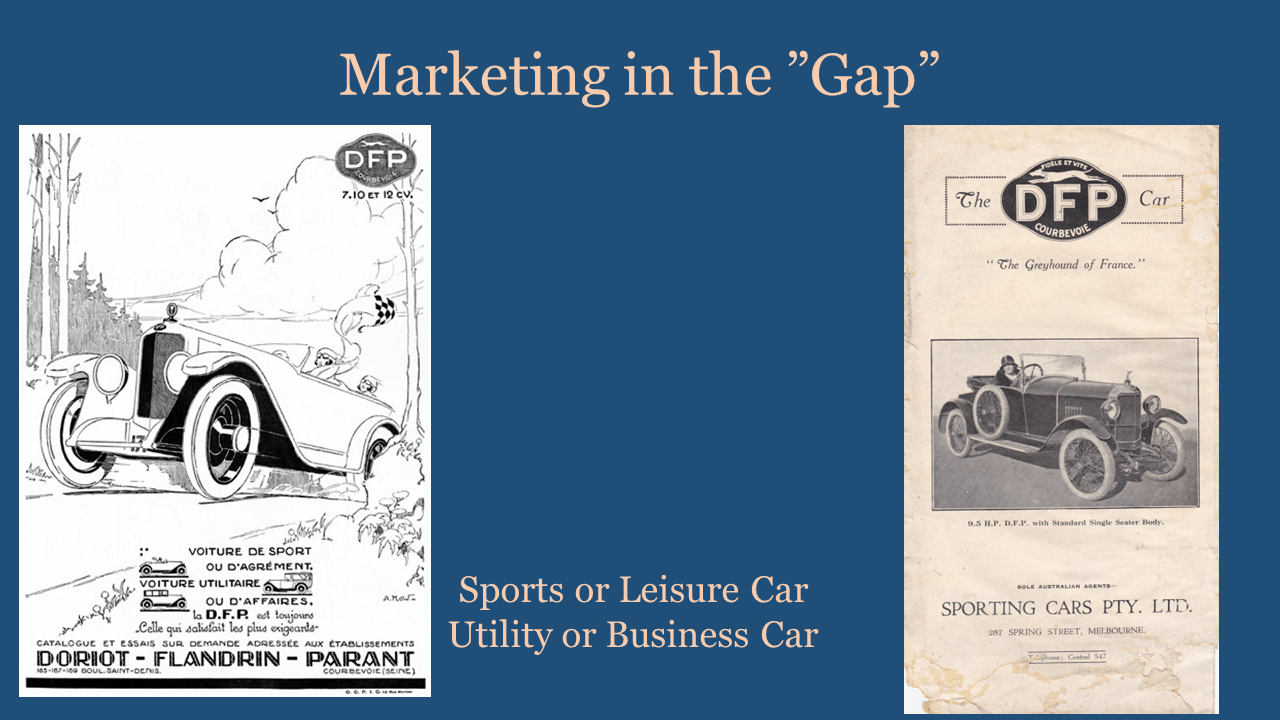

Whereas the poster on the right, notice is emphasizing the very practical aspects of the car for doctors, officials, veterinarians, business travelers, same car, but the same car could be marketed in these two different ways. And in fact, you could actually market the car [00:11:00] for both at the same time. On the left, you have a voiture de sport ou d’agrégement, which means sports or leisure car.

This is high school French, so don’t put a whole lot of weight on it, okay? Or you have a voiture utilitaire ou de fer, in other words, a utility or business car. So here we’re saying, you know, you got something that’s really kind of works for everyone. And you’ll notice on the right, the advertisement for DFP says that the sole distributor of the vehicle in Australia is Sporting Cars Property Limited.

We heard the phrase this morning, race on Sunday, sell on Monday. I have to admit, I believe this has serious limitations. However, These limitations did not apply at this time, mainly because the car that was on the track on Sunday was real [00:12:00] close to the car that was in the showroom on Monday, or could be made really close to it.

Early on, when you’re looking at a small gap like this, yeah, you could race them on Sunday, and that would be excellent marketing for sales on Monday. World War I shows up. What happens after the armistice? We know the automobile industry boomed in the 1920s. However, the question then is, what sorts of cars would companies build, and, at least equally important, how would companies market these cars?

You know, as we saw before World War I, racing could be used to market cars very effectively. Could we still do that after World War I? One of the problems is that the top tier racing cars were getting increasingly different from the cars that were in the showroom. What you were seeing on the track was a lot different than you would see [00:13:00] on Monday.

Admittedly, they could have the same name. So you might imagine that there was some sort of aura or spirit associating them. You know, some sort of brand identity. This is something that would take time to develop. There wouldn’t be that really close relationship. What happened as a result of this, which I think is fascinating, we saw this in the past presentation, you tried to move the racing closer to the other end.

So the real innovation to me with Le Mans race was the idea that the vehicles had to have been produced in certain size batches. So what this meant was it was Increasingly likely that the car that you saw on the track winning something. Obviously there were so many classes you had to win something eventually.

The cars on the track that were winning something could be pretty close to the cars in the [00:14:00] showroom again. If the company had had to make a certain number of them. This worked real well for the race organizers. Because it attracted manufacturers and the manufacturers were attracted to these races because this was an excellent opportunity to advertise their vehicles.

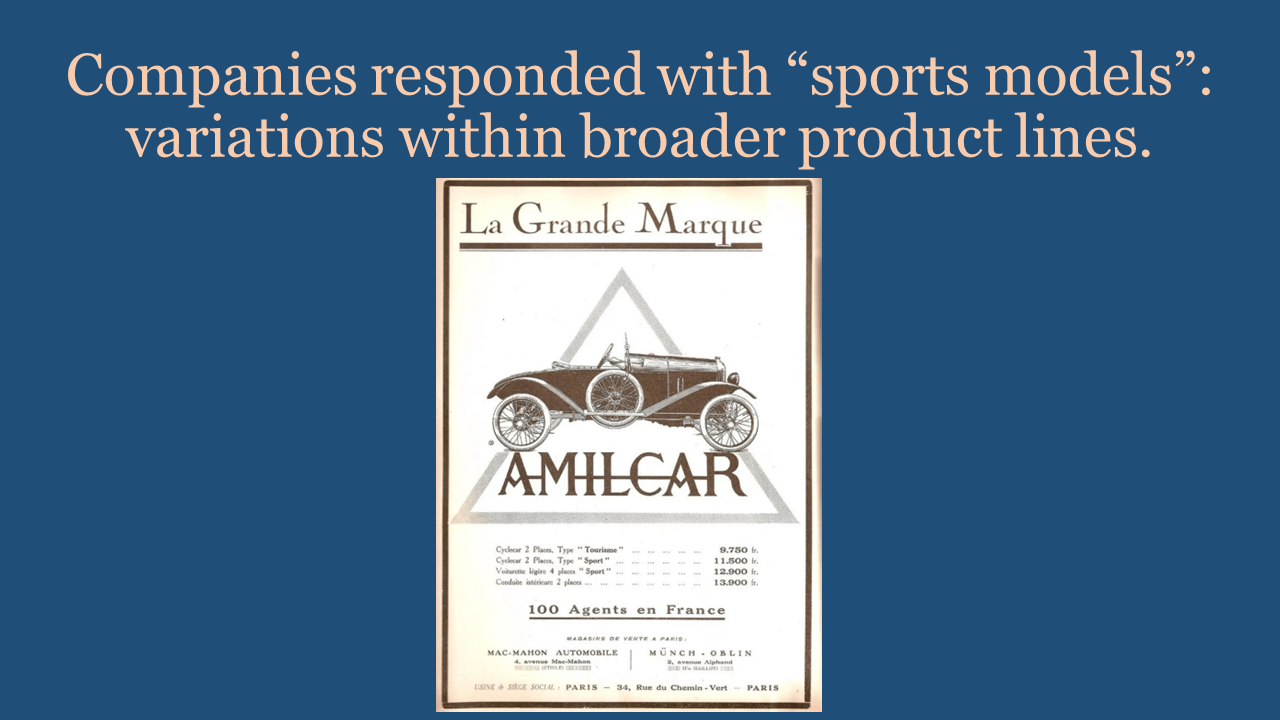

Nice strategy. The result was that companies responded by producing what they were calling sports models. You had a broader product line. But within that product line, you had a model that was differentiated in some way, referred to as a sports model, and that this sports model would satisfy the manufacturing requirements to qualify for the racing.

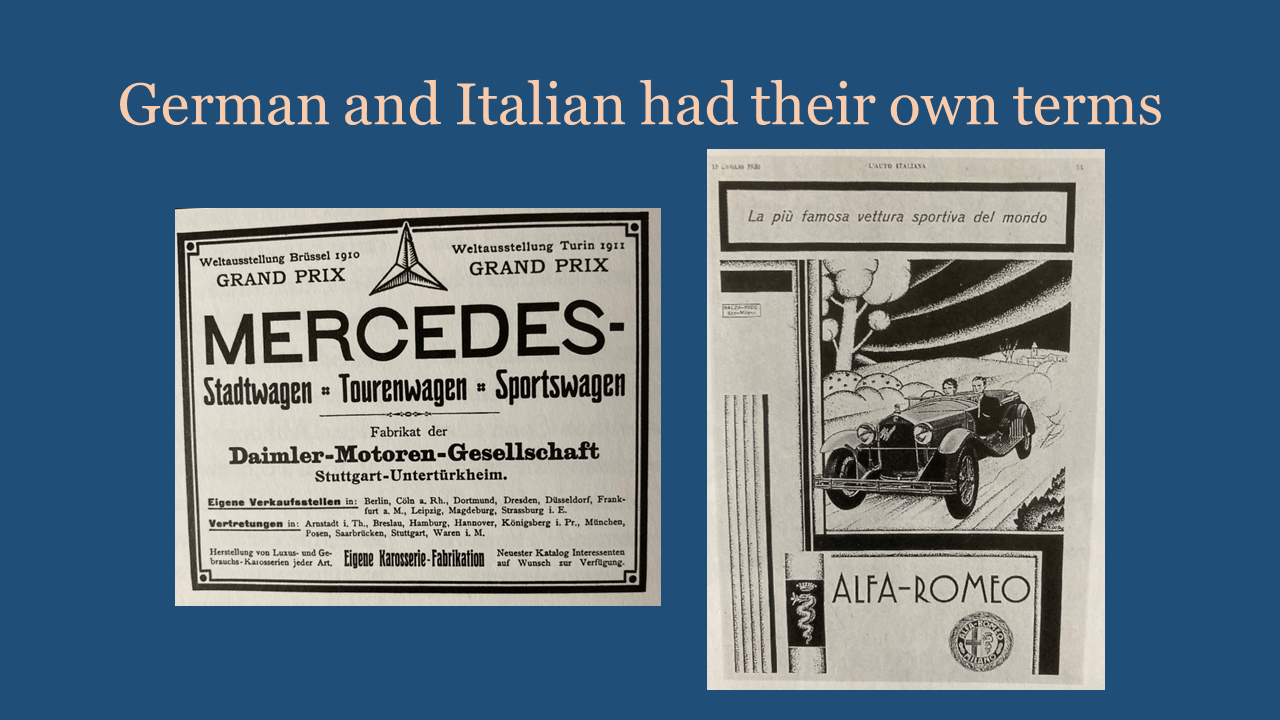

So, for most of the 1920s, we saw sports models. So before World War I, we had sporting cars. Through most of the [00:15:00] 1920s, we had sports models, and this was the reason Amelcar was one that really took full advantage of this. German and Italian manufacturers had their own terms. Mercedes had Stadtwagen, Turnwagen, and, what we’re interested in, in German, Sportswagen.

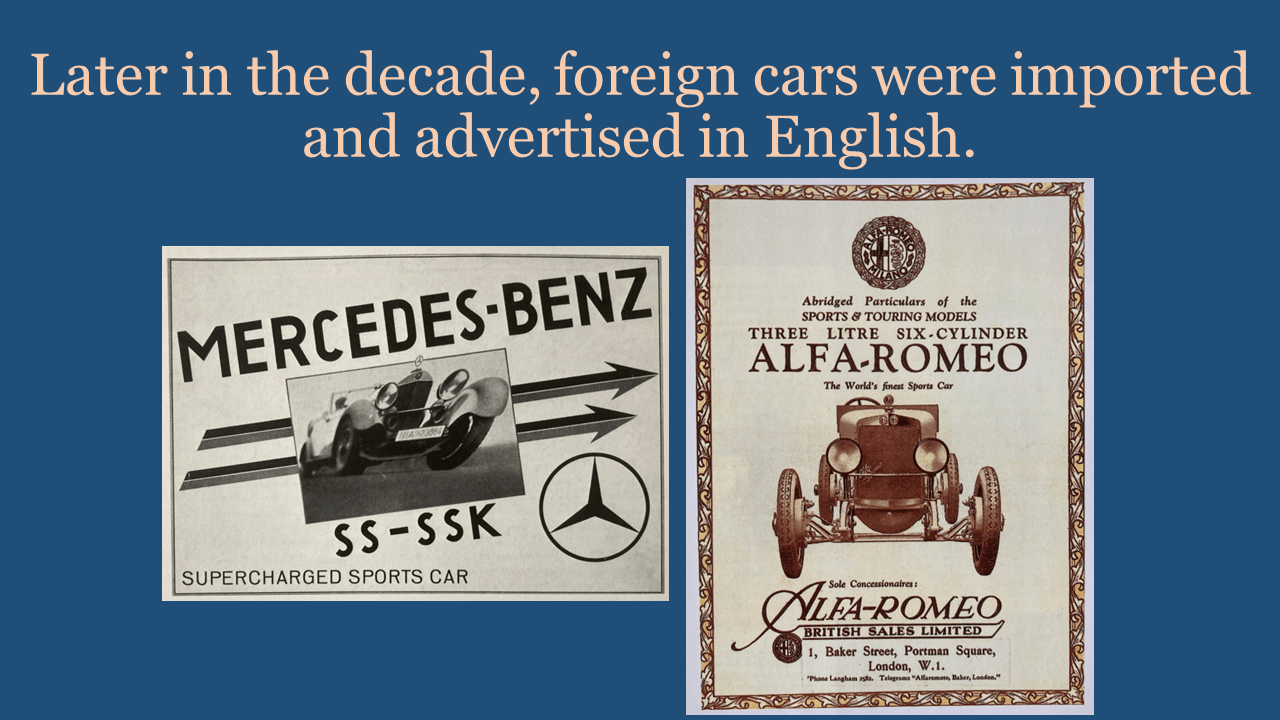

In Italy, Alfa Romeo had Le Più Famoso Vettura Sportiva del Mondo. A German term, and we had an Italian term. Sportswagen Vettura Sportiva. They began selling their vehicles in England. I think these ads are from like around 1928. So, if you’re going to sell your vehicle in England, you’re going to have to advertise your vehicle in English.

So you’re going to have to translate the foreign term into English. So, sportswagen, not surprisingly, was translated as sports car. [00:16:00] Vettura sportiva was translated as sports car. Alfa Romeo used the same slogan, but in English, the world’s finest sports car. I believe that this was how sports car first appeared in English, and moved into the English language as a term.

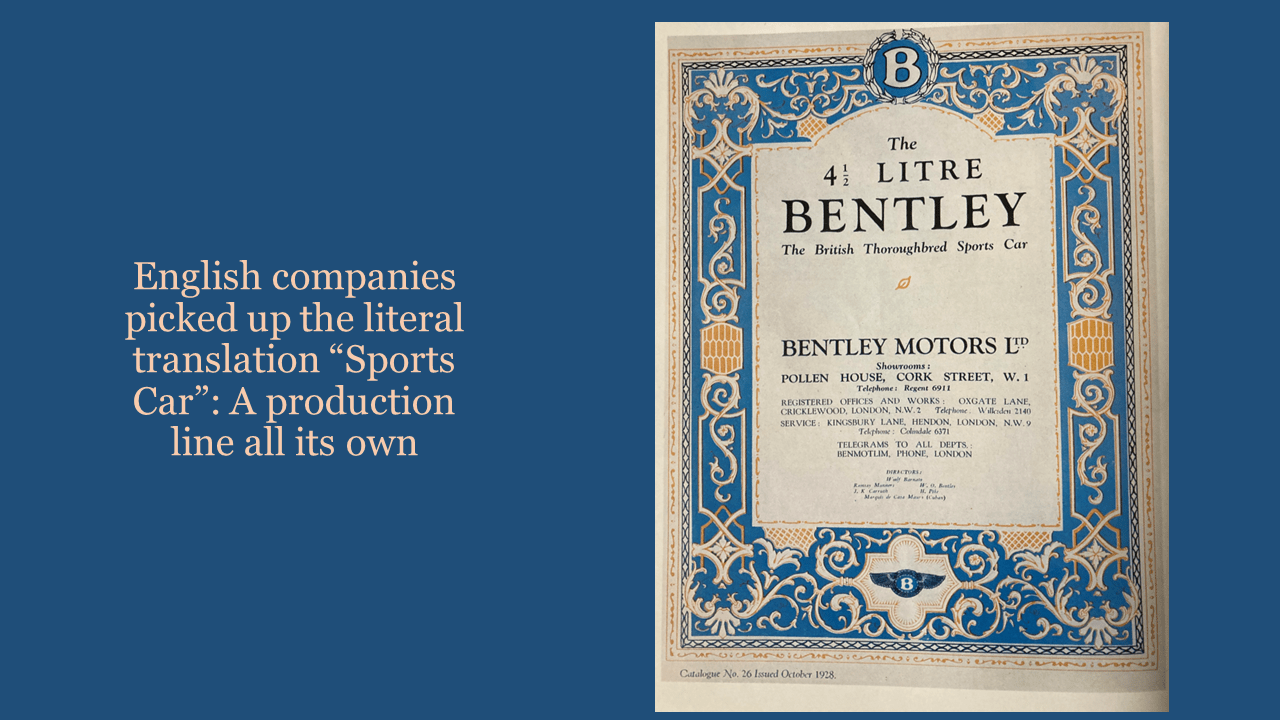

It was picked up by Bentley, and I believe Bentley was one of the first to do so, at least one of the first that I was able to find. So they picked up the literal translations of the German phrase and the Italian phrase, labeled their four and a half liter Bentley the British Thoroughbred Sports Car.

Notice, very clearly emphasizing British, not foreign. And emphasizing thoroughbred, in other words, a distinguished heritage. Also keep in mind [00:17:00] that these were the years that Bentley was winning Le Mans. And most of the um, newspaper stories about these wins emphasized it was a British car. It was only somewhere down in the body of the article that you discovered it was a Bentley.

These were no longer considered sports models. This was a standalone vehicle. Where did the sports and sports car come from? Well, it was a sporting car before World War I. It was a sports model during most of the 1920s. And at the end of the 1920s, and then on into the 30s and beyond, it became a sports car.

But, what did sport mean? And here’s where I go back to the first part of the presentation. This is the theory that you can decide whether or not you agree with. Anything [00:18:00] positioned in the gap between racing cars and at least what were referred to as touring cars is somehow associated with sport.

However, if that vehicle is kind of more in the direction of the racing, it kind of captures the competitive connotations of the word sport. Somewhere in the middle are cars that are sports cars more in the recreational sense of the word sport. And I would argue that over on the right side, there are cars that could legitimately be called sports cars, but in the sense of sport as a style.

What is a sports car? Your call. Thank you very much.

Thank you, Skip. Any questions? Where would the [00:19:00] post World War II hot rod movement fit into this, if at all? Model A Fords, modification of cars that be considered sports cars or not? First of all, I mean, people can use the term what they want. I’m thinking more of this term in terms of manufacturing and marketing.

As opposed to really creating independent vehicles like that. But cars that were deliberately created, not maybe for the personal use so much. as for the intent to make money by selling them. Underline your one definition of sports cars. When I was growing up in the 50s, sports cars were often defined as a car that you could use both as racing and on the road.

And that was a defining idea. The other thing I remember quite well is that when the Sunbeam Alpine came out, it had roll up windows. And hence, was not a sports car. Yeah, that’s true. You know, a lot of the definitions that you really do see are, I would call [00:20:00] them kind of purist definitions. And they can get really technical, you know, it has to not have this, it has to have this, it doesn’t have this.

With this, what I’m trying to look at is the word sport more encompassing, you know, and to address. other uses of the word sports car. Lots of folks would not consider those sports cars. But I think in a broader sense of the word sport. Yeah, they are. Is it fair to say that Detroit rarely use the term? And if so, why?

I don’t know if that’s true, because I know a lot of the Detroit cars are being referred to as sports cars in retrospect. What I would have to do is look and see exactly how they referred to them in contemporary terms. That’s what was interesting about doing this is so many cars from before World War I and during the 1920s were referred to as sports cars in these books that were published after World War [00:21:00] ii.

But if you actually go back and look at the advertisements, look at the road tests in magazines, The word sports car, I could only find it used once in 1925 in relation to an Aston Martin. It really wasn’t until the late 1920s that sports car actually showed up. And even then, it was a slow transition. It appears as if some magazine publishers were adopting the term earlier on than others.

So, you know, it’s not like it happened all of a sudden, it happened over a period of time. And then, eventually, when you came to the SS, that was advertised as a sports car from the very beginning. Let me ask you about three cars. A Jordan Roadster, a Mustang, and a Thunderbird. Which of those would you call sports cars?

Depends on what you call sports. Again, I’d have to look back at the time. I [00:22:00] think you can call those sports cars… Kind of in a recreational or a stylistic sense. They probably wouldn’t fit the more restrictive definitions that drift over to the left of that. I don’t see a problem with calling them sports cars.

Because sports is a very, very encompassing term. I mean, some of them came to extremes. It was like the Packard Caribbean was called a sports car. Can you give a contemporary example of each of those categories of racing a gap? A sports car and a touring car. How contemporary? Today. Oh gosh. Indy, could you say a BMW M4 is a touring and a red BMW or the M4s that they race at the moment.

That’s the racing part. And then, depending upon whether you order the M4 competition or the M4 non competition, whether you order the normal or series that has soft [00:23:00] suspension and, uh, So that one BMW 3 Series can fit. My argument here is, I’m hypothesizing, I might be wrong, a current, say, BMW M4 or 4 Series, in its small, Gas motor automatic transmission mode it sits near a touring car But when in the form when it’s prepared to race it in the German touring car championship or something It’s the pure racing car.

So with that one car the BMW m4, for example, I believe that that Fits in the gap, you know, the current fiat convertible, I would say maybe fits kind of in the middle, but, you know, maybe the about the version kind of move, which actually is sitting in a lot downtown here. I didn’t even know they could import them.

Okay, where do you put the early hot rods? You’ll cut down 32 Ford’s for about the West Coast in the late 40s in the sports car picture. Yeah, [00:24:00] that was. They were also recreational vehicles. That was similar to the first question, but you know, with this, what I’ve tried to do is really focus on the automobiles that were manufactured for sale to the public as opposed to something like that.

All right, thank you, Skip. Thank you.

This episode is brought to you in part by the International Motor Racing Research Center. Its charter is to collect, share, and preserve the history of motorsports, spanning continents, eras, and race series. The center’s collection embodies the speed, drama, and camaraderie of amateur and professional motor racing throughout the world.

The Center welcomes serious researchers and casual fans alike to share stories of race drivers, race series, and race cars captured on their shelves and walls and brought to life through a regular calendar of public lectures and special events. To learn more about the Center, visit www. racingarchives.

org. This episode is also brought to you by the Society of [00:25:00] Automotive Historians. They encourage research into any aspect of automotive history. The SAH actively supports the compilation and preservation of papers. Organizational records, print ephemera and images to safeguard, as well as to broaden and deepen the understanding of motorized, wheeled land transportation through the modern age and into the future.

For more information about the SAH, visit www. autohistory. org.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Brake Fix Podcast brought to you by Gran Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at GrandTouringMotorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at GTMotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and [00:26:00] friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators Fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gumby bears, and monster.

So consider signing up for Patreon today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Livestream

Learn More

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

This episode is sponsored in part by: The International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), The Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), The Watkins Glen Area Chamber of Commerce, and the Argetsinger Family – and was recorded in front of a live studio audience.

Other episodes you might enjoy

Sixth Annual Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History

After a hiatus of two years due to the pandemic, the International Motor Racing Research Center (IMRRC), partnering with the Society of Automotive Historians (SAH), presents the Sixth Michael R. Argetsinger Symposium on International Motor Racing History. The Symposium established itself as a unique and respected scholarly forum and has gained a growing audience of students and enthusiasts. It provides an opportunity for scholars, researchers and writers to present their work related to the history of automotive competition and the cultural impact of motor racing. Papers are presented by faculty members, graduate students and independent researchers.

The history of international automotive competition falls within several realms, all of which are welcomed as topics for presentations, including, but not limited to: sports history, cultural studies, public history, political history, the history of technology, sports geography and gender studies, as well as archival studies.

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center’s Governing Council. Michael’s work on motorsports includes:

- Walt Hansgen: His Life and the History of Post-war American Road Racing (2006)

- Mark Donohue: Technical Excellence at Speed (2009)

- Formula One at Watkins Glen: 20 Years of the United States Grand Prix, 1961-1980 (2011)

- An American Racer: Bobby Marshman and the Indianapolis 500 (2019)