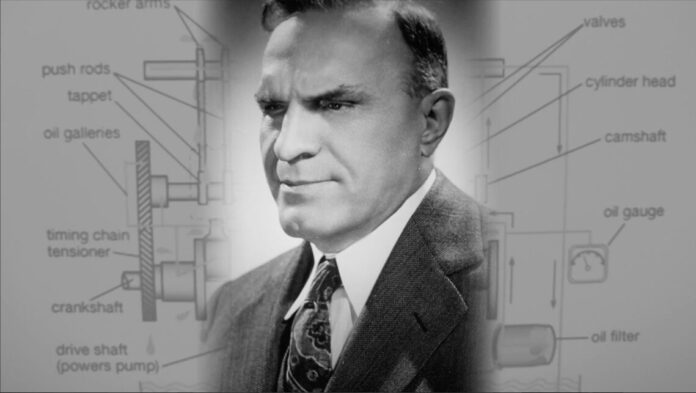

Born in Hagerstown, Indiana, in 1890, Ralph Teetor had normal vision until one day, his hand slipped while working with a knife. The blade penetrated his eye and within a year, he was completely blind. However, Teetor never let his condition define him. He quickly developed a highly refined sense of touch; a trait that would benefit him greatly throughout his career.

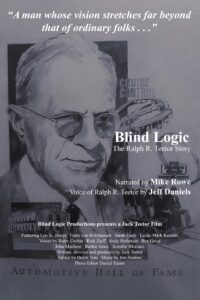

In 1945, automotive engineer Ralph Teetor was responsible for creating the technology we now know as Cruise Control – one of the first steps towards autonomous vehicles. He accomplished this and many other innovations without the benefit of sight. And his great nephew Jack Teetor, joining us tonight on Break/Fix, has taken on the task of retelling his lesser known story.

Spotlight

Jack Teetor - Producer for Blind Logic Productions, LLC

Jack Teetor is a veteran entertainment marketing and distribution executive. Teetor oversees Blind Logic Productions, LLC., producing “Blind Logic – The Ralph R. Teetor Story”, now in post-production. He also runs Sojourn Consulting, LLC., advising independent producers on marketing and distributions considerations.

Contact: Jack Teetor at Visit Online!![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Notes

- Let’s talk about The who/what/where/when/how of Ralph Teetor – Jack please takes us through Ralph’s early life, the accident, and how that didn’t stop him from creating/inventing.

- Ralph also went off to war – there is mention that he worked on NAVY ships? How was he able to do that as a blind person?

- Cruise Control [speedostat] – Where did Ralph get the idea? What was his inspiration? (Something so simple, we all take for granted now).

- Since he was born at the turn of the 20th century, what type of archival footage are you using? Is it a dramatization/reenactment?

and much, much more!

Transcript

[00:00:00] Break fix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the auto sphere, from wrench turners and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of petrol heads that wonder. How did they get that job or become that person?

The road to success is paved by all of us because everyone has a story. Born in Hagerstown, Indiana in 1890, Ralph Teeter had normal vision until one day his hand slipped while working with a knife. The blade penetrated his eye, and within a year he was completely blind. However, Ralph never let his condition define him.

He quickly developed a highly refined sense of touch, a trait that would benefit him greatly throughout his career. In 1945, automotive engineer Ralph Teeter was responsible for creating the technology that we now know as cruise control, [00:01:00] one of the first steps towards autonomous vehicles. He accomplished this and many other innovations without the benefit of his sight.

And now we have his great nephew, Jack Teeter, joining us tonight on this episode of break fix, and he has taken on the task of retelling this lesser known story of engineering. And with that, let’s welcome Jack Teeter to BreakFix. Thank you both very much for having me. And for those of you tuning in, you’re hearing a new voice.

Joining me tonight is my co host, Enrique Rodriguez, who also became visually impaired later in life, and hosts and produces The touch the grass podcast, sharing his experiences about striving and surviving after life changing events like his. So welcome to the show, Enrique. Yes. It’s a pleasure to be here.

I’m actually very excited to be more in like the car space. You know, I grew up kind of a Jeep person, so being able to be here and not only talk about medicine, which is what part of my interest was. But then also being able to talk [00:02:00] about vehicles and like the history of automotive, your tagline for brake fix is every car, except you scratched out car.

And every one has their story. Is that correct? Yeah, that’s right. Yeah. And that’s something that I really try to promote, like on my podcast as well, you know, is that. That everyone’s got these stories. And the fact that Jack is here to be able to share with us one of the stories that seemingly put on the back burner, you know, so being able to share with the world, not only the challenges that Ralph has overcome, but also would love to hear more about Jack.

What even brought you into the ability to be able to have the opportunity to tell this story? Well, Enrique, I think you hit the nail right on the head. So Jack, like all good break fix stories, there’s a superhero origin story here. So we need to talk about how this story of your great uncle came to be.

So why don’t you walk us through Ralph’s life and explain to us what this is all about? Let’s talk about at age five, when uncle Ralph had his accident and he was [00:03:00] prying open a chest of drawers with a knife and he slipped and a knife penetrated one of his eyes. You know, back in that time, the medical profession wasn’t near as advanced as it is today.

Definitely before the age of modern medicine, you know, like when penicillins and stuff started coming around and antibiotics like in the 20s. Back then, really, there wasn’t much to even do for someone who was able to perforate their eye, you know, other than either evisceration, where you remove all the insides, or enucleation, which is removing of the entire eyeball.

That’s exactly right, Enrique. In fact, the infection went from one eye to the other. So within that year, he was totally blind. It’s a condition called sympathetic ophthalmia. What Ralph had happened to him. Doing some research, I found out that Louis Braille, the guy who invented Braille, he had a very similar experience to Ralph Teeter.

When he was a child, he was doing some woodworking, like some carving or [00:04:00] something, and caught himself in the eye with a knife. Just like Ralph did. He had basically the same thing happen, which was the sympathetic ophthalmia. Your body recognizes an uninjured eye as a foreign entity and needs to be like rejected through your immune system.

You know, these days we have immunosuppressant drugs and stuff to be able to hopefully keep the non perforated eye from starting to reject. But I really found it fascinating that not only did Louis Braille, who went on to Braille and many other incredible things for the blind community. But Ralph also, even with the same sort of injury and disability was able to go on to be able to still do like all of these amazing things.

I did not know that story about Louis Braille. That is quite fascinating and a whole story altogether. After he was blind, his parents decided to, on a philosophy of living their life as if Their young [00:05:00] child, Ralph, could still see. In other words, they taught him to look at things with his hands. Ralph chose not to learn Braille.

And to this day, I don’t really know why, but he learned to type. My guess is, is that that’s where he developed his senses of vibration, of feel, of hearing. He had a very keen sense of memory. And so he developed. All these senses by 1902, at the age of 12, he built a gasoline motor car with my grandfather machining each part by hand.

It was pretty a rough car because it was a three horsepower and actually went forward only 12 miles an hour and it only had flat rimmed iron wheels. But the fact was. It was a car and they could drive it, but they had to drive it at the early morning hours before the horse and buggies came out because it bothered the horses, [00:06:00] actually took the car out and drove it and had their fun before the horse and buggies came out in the early hours.

This made news throughout the Midwest. And even I believe it was a New York Herald. It made the news in, in New York City, but they failed to mention the fact that he was blind. They had the article about here’s this young boy who built a car, which was fascinating by itself. In addition to that, he had a love for speed boats.

He had a summer home up about an hour north at Lake Wauwesee where he had speed boats. That’s another whole story too, where he built and tinkered with speed boats with my grandfather. That’s exactly the kind of, like, extra stuff that I would want to know about him, you know? What else does a blind guy who works on engines get into, you know?

Oh, bigger engines that go on the water, you know? That’s, it’s awesome, man. So what’s interesting about Ralph, when you kind of think back to the beginning, born in [00:07:00] 1890, right at the precipice at the dawn of the automobile, and let’s just say jumping forward to when Henry Ford really put everything into motion right at the height of the industrial revolution, all these things in the early 1900s.

He’s about 10 years old. He’s seeing all black Fords coming off the assembly line. Was he immediately attracted to that? Was he interested in that? Was engineering something he wanted to do even before he became blind? His interest in automobiles dated back to the early days before Henry Ford even came up with mass production.

So his passion for engineering became probably two, three, four, five years old before he had his accident because his uncle’s had a machine shop and a company and they were building railroad inspection cars. So he was around mechanics. He just had this passion for machines, tools, and engineering at an early age.

Don’t forget he was near [00:08:00] Indianapolis. So Hagerstown was about an hour southeast of Indianapolis. Indianapolis was actually the car capital of the world before Detroit was. So he would go to the Indianapolis Speedway pretty much every year since it was a dirt track. Well, as his engineering skills developed and his reputation developed, he was going up to the Indy 500.

And meeting with the race car teams and the race car drivers of the early days, like Eddie Brickenbocker and some of the other fellows of those days, and he would tune their engines to the highest performance possible. And he would get a kick out of, well, let’s make the fastest race car possible. I bet that made Harry Miller mad.

Oh yeah. He was providing piston rings to all their engines up to the 60s and 70s. And they had a very good relationship with Indy 500. He was in fact a named chief [00:09:00] steward one year, and then he was named track official one year. And to this day, no one really understands how a blind man can be a track official.

Now I can only think about his. Teen senses of hearing vibration or something, but this is all covered in the documentary to more detail. But the Indy 500 was a place that he’d love to go every year. How does someone so young and who is unable to Read to do math, didn’t even learn how to do braille math because braille does allow you to be able to do math.

Being able to do math is like one of the more important parts of being an engineer. Did Ralph ever talk about how he was able to overcome those challenges or was he more of just an engineer who just kind of felt it out? I learned that from Ralph’s grandchildren, all four of them I’ve interviewed and are in the film.

And one of my cousins mentioned that he was read to, he enjoyed having [00:10:00] people read books to him, but mostly not school books, books of inventors, books of leaders, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Edison. And he was a sponge listening to stories. About these great inventors in terms of mathematics and some other things, he would have books read to him when college came.

This was not very easy, but he wanted to go to engineering school. He went to the University of Michigan 1st. But they turned him down because they did not know how to teach a blind person engineering. Well, he was terribly disappointed. And his older cousin, Neva Deardorff, was going to the University of Pennsylvania on some sort of a scholarship.

And she said, why don’t you come along and we’ll go to the engineering school and meet with the dean. Well, he said, He packed enough clothes for the whole [00:11:00] semester because he was pretty determined to go in. So he met with the dean, Henry Spangler, put his case forward and said, basically, I know most of the mechanics.

I need to learn the theory and other things. And with a little tutoring, I’ll be able to make it through. Dean Spangler had to meet with the faculty and said, come back tomorrow at 10. I’ll give you an answer. The dean met with the faculty And of course, none of them felt that he could make it through beyond two weeks.

They didn’t have the heart to tell him that they couldn’t accept him. So they accepted him. The next morning, uncle Ralph went back and Dean Spangler said, we’re going to accept you and of course, not thinking he would last beyond two weeks, but in any event, he did graduate and he was the first blind student who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and further.

He was the first blind engineer on record in the United [00:12:00] States. And then years later, he came back and got his master’s in mechanical engineering. So he had a lot of books read to him throughout the college process. Tutors, his cousin, Neva. One of the stories, he had to put the mechanics together with his hands, and he convinced them to say, okay, I will put this engineering model together with thread and needles.

And he put it all together by hand. And I guess that quite impressed the faculty. So anyway, that was in 1912, he graduated. That was just a few years before World War I broke out. So it begs the question, so who got a degree at the same time he did, right? Because he had to dictate back to somebody because again, he didn’t know braille and weren’t equipped really to handle a visually impaired student.

So how did that work? How did writing papers, like you said, that he’s doing engineering projects by hand, and that’s all well and good, but he’s going to have to submit something. Or was it all oral [00:13:00] testing? Like, how did that work? Ah, well. As I mentioned, he learned to type and I suspect that probably was in high school.

So he ended up typing a lot of papers and reports in college. In fact, he was the engineering editor for the Whitney engineering club on campus. So he did a lot of typing. And in fact, he wrote a lot of papers. Two that were published, I believe. One about the internal combustion engine. So he did a lot of typing and I suspect that he did a lot of oral repeating of certain things to professors.

Oh yeah, engineers know all about giving presentations, man. A lot of what they do is giving presentations. Now, I mean, we have things like PowerPoint and all these kinds of tools at our disposal, but back then in the early 1900s, somebody’s got to be shadowing Ralph the whole time. Now, I can imagine he moved around with a walking stick, feeling his way through even the campus.

That had to have been quite [00:14:00] the task to overcome in and of itself. Well, and you would think that he would have a cane. He did not have a cane. Wow. The reason is this. Growing up in Hagerstown, it was a little village of 2, 000 people. He would get about town by counting steps, feeling bushes, hearing where the buggies were, hearing people’s voices, counting steps to a certain store, the restaurant, the barbershop, across the street.

And this is where his incredible senses come in and his keen memory. I can only imagine. How he got around campus without a cane. He did have his cousin Neva to help him, and I suspect some other of his classmates helped him before he could learn to count the steps to certain classes. So he probably did have some help, but he never had a cane.

And once he could determine where his dorm room [00:15:00] was to a certain class, probably wouldn’t need much help because he would touch things, he would hear, he would count steps and get around okay. And in fact, he did that throughout his adult life in Agar Sound when he built the company. So it is quite amazing.

You’ve taken us up to 1912, right at the edge of World War I. What happened next? The automotive industry still wasn’t really where it is, let’s say, in the 20s, 30s, and 40s, and especially post war. So that was still a burgeoning enterprise. We’re on the precipice of war. What is Ralph doing from 1912? Up through World War One and beyond came back and he started working at the family business, which had moved from railroad inspection cars to actually building internal combustion engines became the teeter Hartley motor company.

And at that time, Ralph had a real keen [00:16:00] interest in engines. He spent the next few years working on the engines until the war broke out when the world war one broke out, like many young men throughout America, he wanted to serve his country. But the question was actually how, what is the blind man going to do?

Well, he was accepted for civil service. At the New York Shipbuilding Company as a engineering advisor based in Camden, New Jersey. So he was given a desk, but they didn’t know what to do with him. So he kind of sat there, he listened keenly to what they were talking about, and they had received a contract to build torpedo boat destroyers.

And they were driven by Steve Turbine engines. And they had a problem. And the problem was the turbine rotors had to be balanced [00:17:00] perfectly or the boats would break apart at high speeds because they were supposed to be going at 35 knots. That was a pretty good clip for ships those days. And the naval engineers at the shipyard could not solve the problem.

Ralph had already balanced a lot of crankshafts in his days working on the engines. So he had a keen sense of how to balance them by the feel of vibrations and listening. And he suggested to him that, um, He had a way to solve their problem. And of course, they kind of dismissed them, put up an argument, said, Look, you have nothing to lose.

Let me try to balance these turbine engines for you. And so, okay, they let him try and he Balanced them by rotating the rotors in the opposite directions and therefore balance could be achieved and he could [00:18:00] feel it by vibration and his keen sense of listening by the time they got the problem solved.

And he fixed it for him. And the boats built and ready to go. The war was winding down and the boats weren’t used in service. However, They were used extensively in World War II. And so he did solve their problem for him. And as a result, he was hired as the foremost naval engineers for other military shipyards.

But then he went back and worked for the family company again. But you had a lot of things going on in the late teens and early 20s, and you had so many what I consider nowadays boutique brands, which have been merged into things like Ford and General Motors, names like Cadillac, Studebaker, and Packard, and so on down the line, there were so many different brands, and it’s almost like that today, With EVs where you turn around and there’s a new brand popping up, whether it’s Rivian or Tesla or Lucid or whoever, right?

And eventually they’ll all sort of merge together and we’ll get the big three in the EV world [00:19:00] too. What a time to be alive. What a time to be interested in cars and be an engineer because you had the opportunity to go work for some of the most interesting brands out there that, pun intended, were feeling their way through the industry.

But it was a hot time to buy a car. It was an incredible time. What Ralph and his uncles found about their building engines was the critical component of the combustion and the importance of the piston ring. So they actually moved the company. From these custom built engines to piston rings and the reason being their company was not set up for mass production.

So when Henry Ford developed mass production, the whole industry changed. So all the handmade car companies, there were hundreds in Indianapolis. And Megan, they went out of business because they weren’t set up [00:20:00] for mass production. It would take a long time to gear up for mass production. So the Teeter family’s company recognized this and got out of building these handcrafted engines very quickly into manufacturing piston rings.

Because of the importance of the piston ring. And so they started producing piston rings and became the leader of piston rings. And at that time, Detroit was becoming the capital of the automobile world. Because as you say, there’s Cadillac, there’s Chevrolet, there’s General Motors, Ford, there’s Chrysler, there’s Studebaker.

Oh my God. There’s all kinds of brands. So Detroit, because of their capital and the resources. That shifted to the automobile capital of the world and Ralph’s company was then producing for Detroit. It sounds like the whole family is pretty adaptive would be a good way to put it adapting to the changes, not only like in Ralph’s life, but also to the [00:21:00] changes that are happening, like in the whole world to be able to maintain that sustainability.

That’s the operative world and yeah, they were adaptive. That and also. Either some sort of foresight to look ahead and say, we need to adapt. You know, the saying, right? Adapt or die. And in this case, some people, they get stuck, right? It’s that analysis paralysis, but that forward looking as the Italian say, sempre avanti, always ahead.

That’s a great position to be in. And if you can be fortuitous like that, to be in a position like that, that’s amazing. So we won’t call it luck. We’ll call it. At least that sense of genius to be like, Hey, we need to adapt. We need to keep moving with the industry rather than just being stuck here, building engines and disappearing into the dust.

I would take that one step further. You know, Ralph was a visionary. He could see the need for various things. And so. He would come up with a solution, you know, the cruise control, the automatic gearship, the list goes on when he recognized the [00:22:00] importance of the piston ring. I thought that’s kind of cool.

Who thinks about piston rings? Piston rings are really critical to internal combustion engines. Something we take for granted these days, like a lot of the teeter inventions too, which we’re going to get to here. And so I want to explore cruise control or the speedostat back then, you know, more technical term for it or the automatic gear selector, things like that.

What inspired him to think about these? Solutions to what would be back then seemingly complex problems. Things that we take for granted today. I mean, every car comes with cruise control and automatic transmissions and things like that. So where did this all come about? Was this another by product of the war or being involved with the military or some of the other engineering that he was doing?

In 1924, he came up with this. Idea about an automatic gear shift and he filed a patent his manufacturing friends told him that no one is going to pay for the luxury of an automatic gear shift. Well, [00:23:00] history is proved otherwise, so his patent was used for the next 40 years on automatic gear shifts. Then we move into the thirties with the cruise control being blind.

Ralph had a lot of different drivers. He rode with a lot of different drivers. He had many trips to Detroit developing piston rings for every new engine coming out of Detroit. One driver in particular was his patent attorney, who was a jerky throttle brake kind of driver, couldn’t hold a steady speed, and that was very annoying to Ralph, and this was sometime in 1936, he thought, I’ve got to invent something that will keep the car at a steady speed, so for the next Eight to ten years, he tinkered in his basement workshop, and then by 1945, he filed for his first patent on the cruise control, which he called the trademark name Speedostat.

I’m bringing back the Speedostat. I think that’s an [00:24:00] incredible name, man. I love things like that. Tell you what they are right up front. And it’s a play on the Rio stat, which is the electric dial that you can adjust voltage and things like that. So in this case, it’s a dial that adjusts the speed of the vehicle and then locks it in place.

So in a very German way, again, it tells you right up front what it’s all about. From there, it was followed for his patent and then kind of tinkered with it over the next few years or so. It was a slow development process because he had a company that he was responsible for. They were piston rings, it was World War II that he had to deal with.

There was. Unions that he had to deal with. It was all kinds of other things. And somewhere in there, he started a family too. Well, yeah, well, that was, uh, 1932, uh, he Ralph and my aunt Nellie had daughter, um, my aunt Marjorie, their one and only child. How did the original cruise control work? Have you dived into the [00:25:00] technologies?

I’m not an engineer. I’ve looked at these cruise controls. I’ve looked at diagrams. I’ve looked at the drawings and the blueprints of them. I know the early ones were with cables. Most people don’t really understand the technology of it. In 1954, popular science came out with an article about the speed of stat and they included diagrams.

So this was the first publicity of the Speedostat. It got some recognition and on the heels of that publicity, Uncle Ralph made a couple of samples for the trucking industry to try out and use, but interest was really slow. It was just kind of non existent. A couple of years later where things were really starting to kick off.

He kept developing and refining the engineering of it to the point where he was putting them on engineers cars in Detroit. In [00:26:00] 1957, Chrysler, Chevrolet, and Ford were all testing his speedostat. They had a big press conference in Anchorstown, and they had journalists and articles about it. So there was a lot of publicity about it, and It was finally Chrysler who decided to be the first ones and introduce it on their luxury brands in 1958.

Then 1959, Cadillac followed, and then a year after that, other brands followed as well, and then it just Kind of kicked off, but he kept refining it. And it’s really funny that something he invented in the thirties, it took 25 years for it to come to fruition and be adopted by the automotive industry. And now looking ahead 70 years, it’s on every car.

Now it’s evolved a lot since those early days. I mean, when I first encountered cruise control, turning wrenches for myself, it was. Late seventies, early eighties technology [00:27:00] was vacuum based semi electronic solenoid. Now it’s completely digital because we’re all fly by wire. So that one idea, and it’s the progression of many engineering ideas back then it was physical, electromechanical, whatever.

And now we’ve gotten to the point where it’s cruise control in name. But not necessarily harks back to that original design that your great uncle came up with, but what an impact on the automotive industry, much like the intermittent wiper story that we heard about, you know, was it 10 years ago, but you know, things like that, that again, we take for granted.

It’s fun to get that origin story after Chrysler introduced it, they called it autopilot. Then there were naysayers about this device being a dangerous. So Uncle Ralph and his engineers had to educate the safety commissions, law enforcement, and politicians about this device. And in fact, invite him down and show him how to use it.

The naysayers, of course, had [00:28:00] never driven one. They were spouting off before really educating themselves on it, just saying it was a dangerous device. But actually, it was an educated device because there was a warning back pressure on it, so it couldn’t lock in. So there was nothing dangerous about it.

Then after Chrysler, Cadillac introduced it, and they called it Cruise Control. Now that’s the name that Stuck and became the name that everyone is used, but cruise control is fun. It’s easy to say, and everybody remembers it, right? It looks better on an ad campaign on some big Madison Avenue agency that, you know, it’s putting it out there.

It’s interesting about this device because the automotive hall of fame stated that Ralph Teter’s device was the first step towards autonomous vehicles. And I believe in that argument because it really is the first step before we are today, and you look at Tesla, and you look at Google and the technology today, and of course, [00:29:00] we all take cruise control for granted.

Every car pretty much has one. Not only a safety device, but it saves gas for cars again. The kicker here is designed by a gentleman who didn’t drive a car, was being driven around, and he was visually impaired. The irony of it all, but it’s absolutely just amazing. And his passion for engineering, his mindset to always look for solutions to help.

The passenger experience, if you will. But we do need to switch gears. And you came here to also share with us the story that you’ve put together inside of the movie, Blind Logic, which is your retelling of Ralph’s story as we’re talking about it here. So, Tell us about that process. What was that like?

Where does Jack’s story start? What were your beginnings? Like, how did you even get to the point to where you could have this opportunity to tell your uncle’s story? You know, I’m very inspired by my great uncle Ralph, because essentially he inspired [00:30:00] everyone who he met. I remember Uncle Ralph has a child going down to Hagerstown in the 50s and 60s.

And he would take my brother and I down to his workshop and give us a tour of all of his machines and out to his garage to his two or three Cadillacs and show us every little dial in each one and what was different with each Cadillac. And he had a big. Impact on me in the sense that he was very modest, very kind, humorous man at that time when you’re young, you don’t realize the significance of the accomplishments of this man being blind at such a young age.

So, flash forward to 1995, his only daughter, my Aunt Marjorie, wrote a book called One Man’s Vision, The Life of Automotive Pioneer Ralph R. Teter. All the family members, of course, read it, and when I read it I thought, This is an incredible story and it’s going to [00:31:00] make a great movie. Being in the film business back, starting in the eighties, I thought, well, I got to bring this story to the forefront because as you mentioned, Ralph Teeter is pretty much unknown, except in the circles of the automotive business.

And even then he’s unknown except for the old timers. I’m very proud to bring this story to light and tell the story accurately and the way it should be told. And I shared it with some of my filmmaker friends throughout the years, and they concurred, this should be on film. But I wasn’t really ready in my career to make that step until there was a family reunion in 2013 at Lake Wallasey, when my father was still alive, and my Aunt Marjorie was still alive.

They were very Close cousins. And it was wonderful. We all got together in the cousins and the idea of this film came about. So we talked about it [00:32:00] and they kind of looked at me and said, well, where do we go from here? And I said, well, I have to start with writing a script and adapting the book into a script.

And then I have to research. And go through that process, that was a eight, nine year process before I was ready to roll the cameras with something of a game plan to start production. But I really had to have a good idea that, okay, this is going to look good on a script, but now can I bring it visually that presented another problem or a challenge, I should say, I didn’t know what we had in any archives.

I had a few pictures from my aunt’s book. I had some from my father from childhood, but other than that, I really had no idea that I had the vigils to put together a movie. But I went ahead anyway, and I went to [00:33:00] Hagerstown, Indiana. I took drone footage of the town, took a camera crew and we interviewed my four Indiana cousins, all grandkids of Ralph Teeter, in the Hagerstown Museum where they have the perfect circle display.

I started with that. And my cousin, Ralph Meyer in Indianapolis, he laid out all the pictures that he had in his archives on his grandfather, and they were pretty extensive papers, patents, photographs, going back to the 1890s and throughout life. Then we stumbled upon some audio recordings when we came across some 16mm home movies.

I felt that I had a bit of a bonanza here to start with. Was there ever a moment when you were accumulating all the artifacts, that you opened, you know, a drawer or a box and you found something and you go, Wow, I didn’t know my Uncle Ralph was working on that. Was there ever an [00:34:00] invention or a project or something that he left unfinished?

Other than your movie project. That you feel needs to be finished. Oh, he had a lot of inventions and there was a lot of wow moments when I spent a week with my cousin Ralph in Indianapolis, going through the archives, he had a couple of very interesting inventions. One was a pistol grip fishing handle, and one was a.

Very interesting doorknob that was kind of a push and pull lock system. And he also had this very interesting suitcase, especially designed for suits. And none of these really made it to the marketplace, but it didn’t matter with uncle Ralph. He wanted to make things better. He made a better suitcase and a better fishing handle, but he had something like 50 patents from 1919 to 1946.[00:35:00]

So he was always inventing things. When you find so many, like, archival things, what are some of the processes that you go through that, well, like, what makes the cut? You read my mind, Enrique, because I was thinking on similar lines in the sense that nowadays, the word documentary is a loaded term, and there’s different ways to approach it.

If we use a automotive parallel for folks that maybe binged a lot of movies during COVID, you could look at File footage like what Jack is talking about in the sense of like Bongio’s film where there’s some original footage of him driving back in the day and photographs and then some interviews with him right before he died.

Then you have things like Shelby American where it was Carol Shelby narrating the whole thing and they used, you know, All these photographs and whatnot. And then you have things like dramatizations, like framing John DeLorean, where you had big actors coming in and reproducing what was in John DeLorean’s book and things like that.

So I was thinking the same thing. And I’m wondering where did Jack take all this archival [00:36:00] footage and how did you make a movie out of it? 2021, when I decided to start. Filming my cousins that I was not going to do a reenactment type documentary with actors because that was going to be cost prohibitive for me, and I felt that I wanted to do it with archival pictures footage.

To bring a better sense of reality in a historical context, because don’t forget this starts in 1890. It’s a 90 minute documentary covering 134 years of history. So we’re going through quite a few years. I did start with a lot of archives, and then I came back and we digitized everything, and then I had quite a few other challenges, like every image has to be dealt with individually, with the right pixelation, the right ratio for the big screen.

That’s where I called my brother [00:37:00] Dan. Because his skill set is as a photo editor. So I brought him on board from basically day one when I came home with hundreds and hundreds of images, but that was still not enough. So I started storyboarding and realized I had to license some additional image, some footage to really tell the story properly.

And exciting and entertaining, I would use every archival image that I had that was going to be appropriate for the story that was right for the script. Now, interestingly, I wrote a 1 hour script because I was thinking of PBS 1 hour. Or history channel one hour, that would be enough of Ralph Teeter. I could tell the story appropriately, but as I was getting into it, I kept adding more because I found these incredible stories that had to be in the film.

I couldn’t leave them out because they were so [00:38:00] incredible to me. I thought that they’re going to be incredible for an audience experience. I actually added another half hour throughout my two and a half year process of editing this and putting it together because I also realized I needed more people to interview more credible people from the automotive business who would be able to share their insight.

And related to Ralph Teter. So, in other words, I just couldn’t have family people, because the audience would say, oh, well, look at that. All he got was family. And some of the people on that list, one of which has been on Break Fix two seasons ago, is Lynn St. James. Legendary race car driver, rookie of the year in 1992, the Indianapolis 500.

You had Franz von Holzhausen, who’s the chief designer at Tesla. You had Sarah Cook, who’s the president of Automotive Hall of Fame. Mark Kendall, chief historian of the Peterson, things like that. I mean, you really reached out to a lot of folks and then you extrapolate that and you’ve got [00:39:00] big Hollywood names narrating this thing.

Jeff Daniels, Barry Corbin, Rick Zeif, Mike Rowe. How’d you do it? Well, the celebrity voices came at the last part of the process because I hired temporary voices so I could edit the film and put it together. And the reason was, then I could go back and re edit and re edit and add, cut and add more and get it before I committed to getting celebrity voices because once you get the celebrity voices, and you record him, you can’t get him back.

You have to have everything in place beforehand. Getting Mike Rowe took a matter of four months. Getting Jeff Daniels was two or three months. When you’re a filmmaker like myself with no name or reputation, you’re not Steven Spielberg calling his agent and saying, Hey, we’d like to have Jeff Daniels. You gotta really put a [00:40:00] case forward.

You gotta convince them that, It’s a small documentary, but it’s really worthwhile. And here’s why I want Mike Rowe. Here’s why I want Jeff Daniels and Barry Corbin. You just have to build your case and be persistent. They all responded in due time. It takes, you know, the gatekeepers, but they were all very excited about this story.

Once they got involved, they got very excited about it. They were all great to work with. They were all wonderful people to work with. I’m glad you had Lynn St. James on your podcast. She’s such a terrific lady. She is so wonderful in the film and I’m blessed to have been able to get her. And she brings a whole new perspective to the Indianapolis.

Motor Speedway section in the film, your background in Hollywood on the production side. You said, you know, as I’m putting the film together, as I’m editing this, did you do the work yourself or did you have a team of folks that [00:41:00] help you produce the film? Well, I wrote the script directed and I produced, I had a vision from day one.

I wanted to have complete control. And I had a couple of other producers that said, well, we’ll get involved. We’ll help finance. And I said, thank you, but I really want to control everything. I had a couple of script consultants review the script professor and an Indiana historian, because I talk about some things in Indiana.

That happened in 1995, particularly with the UAW. And I wanted to get my facts straight to see if I was neutral enough. My sister, Wendy is very talented and extremely good with the writing word. And she reviewed it and gave me a couple of tidbits to work with. As I say, my brother is a very skillful photo editor.

who is very responsible for all the images that you will [00:42:00] see in the film, probably 400 or 500, that we had to collaborate together on each one. And that was over two years working on that. The editor was based in Indianapolis. He actually was the head of the film crew that I hired. When I first went to Hagerstown, his name is Derek Toe.

He was an excellent cameraman, cinematographer. He knew about independent films. And at the end of our day, I was really pleased and happy with his crew. And I went up and I said, Derek, are you an editor too? And he said, Oh yeah, I edit all kinds of things. And So I, I asked him on the spot, I said, would you want to edit this film?

And he said he’d love to. By that time, he had a sense of the story. And I kind of liked the fact that he was Indiana based. We just got along very well. And I thought, well, why not? You know, I’m in Los Angeles, but we can send files back and forth and I can review [00:43:00] and then give them my notes. And I would storyboard.

and get all the images ready and send him like the first act and the second third fourth and so on and so forth and then we would go by act so we kind of just plotted through over the several years the film covers 134 years of history What we didn’t cover in the first segment of this episode is the end of Ralph Teeter’s story.

And what I think a lot of people don’t realize is how long he lived. He lived until 1982. So he was well into his 90s before he left us. And what a long and incredible life. And where we left off in his story is what happens next. He did all these amazing things in the early days, especially in the thirties and the forties, and he became the president of the SAE, all this kind of fun stuff.

He developed the perfect circle company, as you mentioned, which developed piston rings and things like that. And we fast forward to the 1960s, the height of the hot rod era, car [00:44:00] manufacturing is changing and he sells the company to Dana. Yeah. A name that jeepers like Enrique would be familiar with because they build all sorts of parts for off roaders, which eventually then got sold to Mali, which is a German company that’s still around today.

So from the 1960s to the 1980s, the last 20 some years of Ralph’s life, you’re around, you know, you mentioned spending time with him and his shop and all that. What were his golden years? What was his retirement like when he finally sold the business in the sixties and said, you know what? I’m done. Well, he wasn’t done.

In fact, when Dana came at that time, Ralph was chairman, they were talking up with Dana and they liked the fact that they had similar goals. Dana was heavily involved, as you say, in automotive parts. And it seemed to be with the board that this would be a good marriage. And at that time, the board of directors, they were all in [00:45:00] retirement age.

They felt that this would be good for the company, and that Perfect Circle brand would remain intact, and the factories would remain intact, because Uncle Ralph was very concerned and loyal to his employees, and he wanted them to have a future. And so, the company sold in 63. He regretted that decision for several reasons.

First of all, uncle Ralph thought that he would be kept on as chief engineer, the speedostat because he still had things to do with the speedostat and improve it. He was kind of forced out and the other board of directors retired and Dana came in and a whole new culture took place in that small Indiana town.

And there was three other factories and other small towns nearby. Bye. But the culture changed, they were corporate people that came in and [00:46:00] they didn’t have a sense of responsibility to the small communities like Ralph did and the company did and they built libraries and they did things for the town and they did so much for the communities.

And if something was needed in town, Ralph and Perfect Circle would give it to them. But Ralph didn’t want to retire and he formed another company called Tedco to foster his inventions and developing his other things. So he worked on that. He wrote papers and he still was heavily involved with his educational scholarships that he started at SAE, Indiana Tech, and another university.

He also donated. Earlham College in Richmond, the Joseph Moore Museum needed a planetarium. He donated money and they built a planetarium. So he did a lot of philanthropy. That was sort of what he was doing as his [00:47:00] retirement. He was giving back. So it really sounds like a man of the community. And especially when you’re so reliant on so many other people to just, like, have your everyday life be so, quote unquote, normal.

It really makes me happy to know that he was someone who was so willing to give back to this community, who was able to not only provide, like, such a good environment for him to be able to do the things that he wanted to do, then was able to allow the community to also be lifted up in that way, even without the company.

So outside of the film paying tribute to Ralph, did the town bend at some point, turn around and dedicate a monument to him? Or is there a museum in his honor and his name, or is it just the names on the side of the buildings because the endowments that he made? The town went through a few phases. The final perfect circle piston ring factory closed.

In 1995 in Hagerstown, 100 years [00:48:00] after the company started, there is now a monument there to honor what Perfect Circle did for the town. They also had a factory in Richmond, Tipton. They had four factories all together. But they do have a monument there. There is another plaque that was recently put in this year for Ralph Teeter.

What also happened after Ralph died in 1998, he was posthumously inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Today, he has an exhibit there. At the Automotive Hall of Fame Museum, and that’s where we filmed Sarah Cook, the president of the Hall of Fame. And it’s a wonderful exhibit. They have a cruise control and they devote the whole section to Uncle Ralph.

So his legacy lives on there. He is being inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He’s in the National Science and [00:49:00] Space Museum. They have a cruise control there. His legacy does live on, but Ralph Titor is still unknown, and I’m hoping this film will expose his story to a new audience about what this man has done and was able to accomplish.

He was a very modest man. He would be happy that I’m doing this. I know Aunt Marjorie, who has since been Passed away in 2019 and my dad passed away in 2016. They both would be thrilled that this story is coming to light now because they believe that this story should be told, and I’m happy that I’m the one to bring it to the forefront now.

It seems like he was very much about making the world a more accessible place to others. So I was wondering what kind of like accessibility you’ll be bringing into the film at all. Narrations for stuff or any sort of other sorts of accessibility options for watching the film? I do want to have something [00:50:00] for the blind and I believe it’s an extra audio track.

Yeah, that’s usually what people have accompany any sort of like visual medium. I know that you can go to museums and you just like plug in your headphones and it’ll be an audio description of whatever you’re looking at. So I was wondering if like your website is going to have some descriptions of any of the pictures or anything that you’re going to be using during the film.

Or is it a documentary much like where not like planet Earth where I can sit down and listen to it? And just hear the entire thing and get the full story just through the audio. Or are there other ways that I’m other people who, myself included, who are visually impaired and blind to fully appreciate the art that you’re creating in your film?

In my website, I have a page devoted to blind institutions. I’m hoping that people that come to my website see that page, who know people that are visually impaired, that they might be able to direct them to the resources I [00:51:00] have. And I’ve been also reaching out to blind institutions because I want to have some charity screenings.

I believe in Washington, the National Institute of the Blind. I reached out to them a couple of years ago. They’re aware of Ralph Teeter and I’m hoping to do something with them. The answer to your question is I’m definitely moving this direction and I want to do the right thing and make it available and accessible.

That’s fantastic. And thank you for telling this story. I know that when I became blind, it was very much a crisis of identity and I really didn’t know how I was going to be able to continue to go through and continue to live my life despite my difference in ability. And especially with something as severe as going blind, like in your late 20s, it’s a huge change to your life.

So it is stories much like Ralph’s that are the ones that helped me get through the hardest of the times when, you know, everything was just [00:52:00] not looking great. I was in a bad place mentally. It was stories a lot like Ralph’s and other visionaries who have been able to create. a life that works for them, no matter what sort of obstacles come through.

So I do think that this is a fantastic film that you are creating and like, not that I’ve seen it yet or anything, but I do want to just express my appreciation for sharing such a beautiful story. I’m making this film in large part for people like yourself. The inspiration to make this film was overwhelming because how inspiring Ralph was.

And from day one, I wanted to make a film that at the very least is inspirational and brings inspiration to people on many levels. But like yourself, visually impaired, it means more to me than anything if I can help inspire people in their lives to see [00:53:00] what this man has done and what Every individual is capable of doing if they really work hard at it and they concentrate.

And one of the things that Ralph Teter had was mental vision that was beyond what we can really fathom as ordinary people. But we all have strong mental vision if we really put it to use and use And hopefully this story will inspire people. To maybe make the world a better place, maybe make their lives a little better or work harder and give back to the community.

If this film does that in any little way, then I have done my job well. Mission achieved. Jack, we have reached that part of the episode where I always like to remind our guests to share with us any shout outs, promotions or anything else you’d like to share that we haven’t covered thus far. I’ve been working with the [00:54:00] Hollenbeck Youth Center in East LA, where we help kids from gangs and broken homes through athletics, through educational programs and mentoring.

We help them achieve a better life. I’ve been doing this for 25, 30 years. That sounds really fulfilling, man. It is. So I’ve been giving back that way. I’m also on the board of advisors for Artists for Change. Where we make media that has a statement to help social services and so on and so forth. So I do try to give back and that brings me a lot of pleasure helping kids and I am going to be having two premieres, one in Detroit and one in Los Angeles.

But the dates and the venues to be determined, I know the Automotive Hall of Fame wants to have a series of educational screenings. Clemson University is going to be having a screening, likely in May or June or in the fall. [00:55:00] This month, April, we’re going to be having a screening at Earlham College during their events around the total eclipse.

And we’re going to have a screening in Hagerstown as well. And all these dates will be on my website. And before we sign off, Enrique, I want to give you the opportunity to tell our audience a little bit more about your show, Touch the Grass. So my name is Enrique. I go by Ike on the internet. And I’ve just recently started my own podcast, The Touch Grass Podcast, where we focus on where people are overcoming their everyday challenges in life and what they do to make them happy, just to be able to have a happier life.

So, you can check out more episodes of The Touch Grass Podcast on my YouTube channel, youtube. com slash at. Ikemedia, I Q U E, media. And I also have a website as well where you can find all the rest of my socials. That’s I Q U E dot me. M E, as in the first two letters of media. [00:56:00] You know, I hope to see you on the internet sometime soon.

Known primarily for his invention of the cruise control, Ralph Teeter, also served in World War I, was a crusader for his workers rights, and posthumously inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Ralph Teeter’s life spanned the entire development of the American automobile industry. He was granted 50 patents from 1919 to 1946.

And to many Indiana families, Teeter is remembered for his generosity, respect, and loyalty to his employees. The documentary film of Ralph Teeter’s life is currently in post production and scheduled for release in 2024. And you can learn more about it by visiting www. blindlogicproductions. com Or following at Blind Logic Film on Twitter and Instagram, or reaching out to Jack Teeter directly at jack.

teeter on Facebook. And with that, I have to thank you both for getting together with me here on another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcast. [00:57:00] And what’s most important about this is it’s not even really about. The automotive part of this, which is an interesting corner case in the many stories of what we call the auto sphere.

It’s another stone that we’ve turned over to find something that we didn’t know about before. It’s been an education, but I think the moral to the story is that of adapting and overcoming. Challenges and adversity in life. And if there’s anybody, especially as an automotive and vehicle enthusiast to be inspired by, as Jack said earlier, it’s his uncle, Ralph.

So watch the film, read his aunt Marjorie’s book, learn as much as you can about Ralph Teeter. And at the end of the day, be like Ralph. Definitely. That’s fantastic. Oh my gosh. Thank you for having me, Eric. It was, uh, really just a pleasure to be here. And thank you for talking with us, Jack. I cannot believe that I even got the opportunity to be able to hang out with you and just learn more about such an incredible person.

Well, let’s meet in person someday. And I thank you both for [00:58:00] having me, Eric. Thank you so much. For this opportunity, I enjoyed it immensely.

We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of break fix podcasts brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article at gtmotorsports.

org. We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as 2. 50 a month, you can get access to more behind the scenes action, additional Pit Stop minisodes, and other VIP goodies.

As well as keeping our team of creators fed on their strict diet of fig Newtons, gummy bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon [00:59:00] today at www. patreon. com forward slash GT motorsports, and remember without you, none of this would be possible.

Learn More

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others by way of Break/Fix and GTM. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

Known primarily for his invention of the Cruise Control, Ralph Teetor also served in World War One, was a crusader for his workers’ rights, and posthumously inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Ralph Teetor’s life spanned the entire development of the American automobile industry. He was granted fifty patents from 1919 to 1946. And to many Indiana families, Teetor is remembered for his generosity, respect, and loyalty to his employees.

The documentary/film of Teetor’s life is currently in post-production and scheduled for release in 2024; and you can learn more about it by visiting www.blindlogicproductions.com or following @BlindLogicFilm on Twitter and Instagram or @jack.teetor on Facebook

Update: Los Angeles, CA – April 17, 2024

Blind Logic Productions announced the association with Video Caption Corporation for the creation of an Audio Description (AD) track for their documentary film, “Blind Logic: The Ralph R. Teetor Story.”

“We are being proactive in making this film accessible to millions of blind and visually impaired individuals,” stated Jack Teetor. Video Caption Corporation has been providing high-quality audio description services since 2010. Tiffany Thomas, SVP Sales & Customer Service, further stated, “Ralph Teetor was an inspiration to all, and it is only fitting that this film is made accessible to this significant audience.”

Gary Wunder, Editor of the Braille Monitor, the flagship publication of the National Federation of the Blind, commented, “The story of Ralph Teetor is certainly one which our members would be interested in learning more about.” Wunder further stated, “The National Federation of the Blind is a group of blind and sighted people who have come together to improve the social welfare of the blind and to further our integration into society.”

The upcoming documentary follows the extraordinary journey of Ralph Teetor from childhood blindness through his life of fierce determination and distinctive mental vision to become an inventive, insightful leader, and philanthropist. Ralph Teetor’s life spanned the entire development of the American automobile industry.

Emmy Award winning host and narrator Mike Rowe is providing the narration and Emmy Award winning actor Jeff Daniels is voicing Ralph Teetor, among many other extraordinary actors voicing characters.

This film features renowned trailblazers Lyn St. James, legendary race car driver and 1992 Indy 500 “Rookie of the Year,” Franz von Holzhausen, the visionary Chief Designer at Tesla, Inc., Sarah Cook, the remarkable President of the Automotive Hall of Fame, and the illustrious Leslie Mark Kendall, Chief Historian at the Petersen Automotive Museum.

Credits include award winning Editor Derek Tow, Composer Jim Andron, Photo Editor Daniel Teetor, and Sound Editing, Effects and Design by the award-winning team of Darren King, Nikola Simikic, and Amanda Roy. Written, directed, and produced by Jack Teetor, this documentary is based on the book “One Man’s Vision – The Life of Automotive Pioneer Ralph R. Teetor,” by Marjorie Teetor Meyer.

Blind Logic Productions is in the planning stages for Detroit and Los Angeles premieres to be announced. This film is scheduled for release in late 2024.

Special Co-Host

Joining us tonight is co-host Enrique Rodriguez, who also became visually impaired later in life, and hosts and produces the “Touch Grass” podcast sharing experiences about striving and surviving after life changing events like his.

“My name is Enrique, I go by ique on the internet. video creation has always been a hobby of mine while i focused on getting into medical school. in 2021 I went blind. it was really hard but i put the same dedication i put into medical school into learning how to be blind. during this time i decided that i should use my platform to help people. i want to create a community that focuses on kindness, empathy, respect, and love. everywhere i go on the internet there is so much negativity (lookin at you YouTube comments) and i want to provide a space where we all can just hang out and have a laugh. so please, check out all of my channels, join the discord, subscribe, check out the patreon etc. and i hope to have created something that brings you joy. have a beautiful day!” – Enrique Rodriguez.