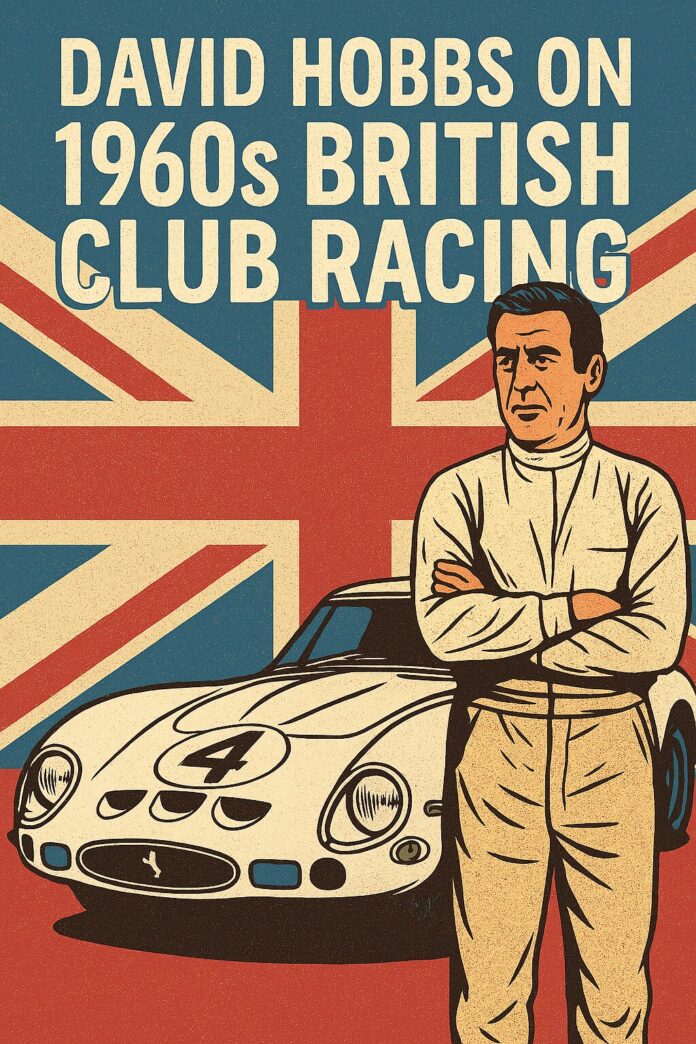

Every so often, Break/Fix takes a detour from its main episodes to deliver a Pit Stop Mini-sode featuring bonus content that digs deeper into motorsport history. This time, we had the privilege of sitting down with legendary driver and commentator David Hobbs to revisit the vibrant world of British Club Racing in the 1960s, and to explore the fascinating story behind John Coombs’ famous white Ferrari 250 GTO.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

Hobbs’ journey into racing began humbly in 1959, behind the wheel of his mother’s Morris Oxford. By 1960, he was campaigning his father’s Jaguar XK140, still learning the ropes and discovering the importance of racing tires the hard way. As a Jaguar apprentice, Hobbs found himself under the watchful eye of Lofty England – Jaguar’s managing director and former Le Mans-winning team manager – who quickly recognized his talent.

Despite being chastised by supervisors for neglecting his apprenticeship duties, Hobbs was soon tapped to test prototype cars at Silverstone. That moment, walking past skeptical managers alongside Jaguar’s top brass, marked the turning point in his career.

Spotlight

Learn more about David Hobbs and his fabulous racing career on this episode of Evening With A Legend. Go Behind the Scenes via our Patreon.

Synopsis

On this Pit Stop mini-sode of the Break/Fix podcast our team, consisting of Crew Chief Eric, William Ross (Ferrari Marketplace Podcast) and Jon Summers (The Motoring Historian) delve into the history of British Club racing in the 1960s with legendary pro-driver and commentator, David Hobbs. The discussion covers David’s early racing career, the dynamics and culture of club racing during that era, and significant figures such as Lofty England, John Coombs, and various renowned drivers like Graham Hill, Mike Hawthorn, and Jack Sears. Hobbs shares personal anecdotes, his experiences with different racing cars, including the famed white Ferrari 250 GTO and Jaguar E-Type, and his interactions with key personalities in the motorsport world. The episode also touches on the transition from amateur to professional racing and the evolution of race car engineering.

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] We always have a blast chatting with our guests about all sorts of different topics, but sometimes we go off the rails and dig deeper into their automotive and motor sports pasts. As a bonus, let’s go behind the scenes with this pit stop mini episode for some extra content that didn’t quite fit in the main episode.

Sit back and enjoy and remember to like, subscribe and support break fix on Patreon.

Crew Chief Eric: It is always fun to get back together with John, the motoring historian, and William from the Exotic Car Marketplace. But today is extra special because we are gonna take a deep dive into 1960s British Club racing with. None other than legendary pro driver and commentator David Hobbes. So I wanna welcome David Hobbes back to break Fix as we dive into this interesting part of Motorsports history.

David Hobbs: Well, good afternoon, gentlemen. Thank you for inviting me for a, a recap of 60 odd years ago.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, David, this comes about because John, William and I have been working on a [00:01:00] project about John Coombs and his famous white Ferrari, two 50 GTO, and when we were digging into the history, you start to realize how small the motor sports world is.

Your name starts popping up because that’s when your career was starting to come about. And so we figured, well, let’s ask a living legend about living history. So let’s dive into British Club racing in the 1960s. Can you take us back? Well, British Club

David Hobbs: racing in the 1960s was actually very, very healthy.

And of course, in those days it really was club racing. The first two cars I drove in 1959, I drove by Mums Morris Oxford. Which was hardly a racing car. I drove it, took it from the tracks when I didn’t have it towed, how that is. And in 1960, I drove my dad’s XK one 40. But unfortunately I was so naive and, uh, so raw that I had never quite understood the, uh, ports of racing tires.

And I raced out on Michel X. In the very first race with I ever turned at, at Alton Park on the last [00:02:00] lap of a GT race and was outta the race. I, I modified that ’cause I was actually a Jaguar apprentice at the time. I had started off buying, being a Damer apprentice, but then I became a Jaguar apprentice ’cause of my dad’s affiliation with Daimler, with his, uh, automatic gearbox.

I, you know, I, I chose the school, so I couldn’t go to university, so I became an apprentice. But of course, I got so involved in the racing and luckily, loft England, who was the managing director of Jaguar when I became a Jaguar apprentice, was the team manager who won Lamont for. Jag in 1950, what? Five, six, and seven.

Lofty was a team manager. He had worked his way through the company and by the time I was the apprentice, he was the managing director, but he also was a clerk of the course, what you’d call a chief steward at lots of silvers to the club racers run by the British racing driver. Luckily for me, lofty took rather fancy to my driving style, and so he was a great help.

I had, uh, a funny incident and the apprentice supervisor, whose name was Harold Barker called me into [00:03:00] his office and tore me off a strip and said I was the worst apprentice I’d ever had. I was never there. I’d ever went to tech, I’d ever passed any examiners, which I didn’t. I. I did spend a lot of time at the racetrack.

By 1961, I was driving the Low Elite, which my father’s company had bought me to help promote the gearbox because it had dad’s automatic gearbox in it. So although Harold Barker tore me off this terrible strip, just said, I dunno what you’re gonna do ho. He said, I think I just don’t see a life for you.

You’re gonna be probably be homeless. And he said, you’re absolutely completely useless. Well, luckily a couple of weeks later I was working in experimental department and the foreman called me. I was, says here, Hobbs. He says, Mr. England wants to see you in his office. So I thought, oh, blindly. This seems got a bit outta hand now.

So I went up to the office and Lofty said, oh Hobbs, we have an experimental car. We have a prototype car, and we’d rather like you to take to silver to drive it for us. Would would you be able to do that? I said, I’m sure I could. So, so the next thing, I’m walking through the [00:04:00] main office block with the Lofty England as the managing director with, uh, Jim Haynes, who was the, uh, chief engineer at Jaguar.

Wally Hassen, who was the chief engineer man, and, uh, Mike McDowell, who was the competition manager for Ja. And we walked past Mr. Barker’s office and I was there. He was look in the door while I’m walking down with all these heavy hitters and say, oh, afternoon, Mr. Barker’s still here.

That was the high point of my apprenticeship. Anyway, we did go testing and Michael Parks, if you remember the name, Michael Parks was going to run me that afternoon. He and his girlfriend were there and his girlfriend. Ultimately became Enzo Ferrari’s personal secretary. And she is still alive and kicking, apparently living in Italy and I just can’t remember her name.

But she was a very bright young spark and uh, Michael was very attracted to her. But anyway, I spun the car going through the old Abbey curve, which in those days was pretty much a flat out lefthander. It’s gone now, but I spun it the flat spot, all the tires ’cause they hadn’t got [00:05:00] his spare tires. So we went back to the factory.

So during 1961, dad had a bit of a windfall in the Westinghouse breaker signal. Bought some shares in the company and I thought it’d be a great idea if we raced the loads of elite with the gearbox, which of course the big thing about dad’s box was it was the four speed, the friction drive, no fluid drive.

So it used very little power. It had four speeds with automatic or and full manual override. So it made a perfect racing mops and we were very successful in the Loads League. Well, or races. Of course, during that time, lofting was a, was a big supporter, and when I finished my apprenticeship at the end of 1961, a lot of things happened.

The Army draft finished at the end of 61. I finished my apprenticeship in December the 31st, and I got married on December the 16th. And Lofty had got me a professional drive with a guy called Peter Berry who had a 3.8 mark, two Sudan and an XKE, both in green. Bruce McLaren had driven for him in [00:06:00] 1960 and he asked me to drive for in 1961 and Lofty got me that drive in 1962.

So when I left apprenticeship, I got up to a flying start with my racing career by driving for Peter Barry. And of course our biggest competitor, one of our big competitors, was for two big competitors, a key endeavor, which is run by a guy called Tommy. So with, and John Coon. So I met John Coons fairly soon.

You know, after leaving Jag. He knew that Lofty England knew me and thought a lot about me. Funnily enough, in my last year while the apprentice supervisor was slagging me off, I got a call to see if I’d go to entry because it was the British Grand Prix today entry, and one of the supporting races was a GT race.

And I rushed up there. He said, can you go and drive for Tommy? Sat with an Ike endeavor, E type, and of course I rushed up to Adrian. By the time I got there, Jack Sears, who was another very, very, very good amateur driver. I mean, he is a farmer, but he [00:07:00] was a hell of a driver. Unfortunately, Jack Sears was also there and he hadn’t gotta drive that weekend.

So before I got there, they had actually put him in the car. They did gimme some lapse in it. I was a bit nervous ’cause I’d never driven a big car before. I’d only ever driven the elite, so I was used to about 85 horsepower, not whatever. The Jag gave a couple of hundred, 250, something like that, and a much bigger vehicle.

Obviously John Coons was there at that meeting as well because Graham Hill was driving John Coombs as E type. This is before the Ferrari came along. Coombs was very successful. Graham Hill drove for him in the, uh, in the 3.8, mark two, which was also white. He drove for him an E type, which was white, and then of course they got the.

The two 50 GTO, which of course was a hell of a car, and they had some very spirited races with people like Tommy, who was a pretty good driver. Michael Parks drove for him. Obviously, he was a very good driver and some chap called Sterling Roth drove for him as well. In in the number seven before the GTO, he had a, a [00:08:00] Ferrari, uh, two 50 short wheel base, which was a hell of a car.

Those races used to be really exciting because they were very, very. Compared to today. I mean, these were modified street cars. You could take the seats out or you could put lighter seats in and you could do other weight saving, but you couldn’t do much. They didn’t. They didn’t have a space frame like most race cars do today, so they were much more difficult to actually get stiffener.

The chassis were never stiff. But it made them very exciting racing and the, and the public loved it, and John Coombs was a huge part of that.

Crew Chief Eric: David, there is so much to unpack here. I’m sure we all have questions.

Jon Summers: Our understanding is that Coombs bought this GTO because the E type was not competitive. And in an interview that John Coombs had with.

Simon Taylor from Motorsport Magazine 15 years ago now. He says that he had a meal with Bill Haynes, where he said to Bill Haynes that this car’s like a pendulum. If you don’t make it lighter, [00:09:00] I am going to have to race my Ferrari. And coming outta that lunch, this white Ferrari apparently spent the winter of 1962 at Jaguar.

Evolving and this process gave us the lightweight e type. That’s what we think happened. Do you have any insight on that or were you in Daytona meeting, bill France at that time?

David Hobbs: I’m afraid I don’t have any insight on that. No. Uh, that would’ve been above my pay grade, but I couldn’t believe that a lot of people have done that, taken cars that take ’em apart, and obviously the lightweight E type was very, very good.

It still wasn’t quite as good as the Ferrari. I dunno whether it had a bit less power. The V 12 and the Ferrari was a great engine and the chassis was pretty good too. The uh, GTO was in the end was quicker than the lightweight. Now obviously, lightweight E types now have evolved enormously. They’re not really jags anymore.

They’re so different. But, uh, yeah, so I can, I can believe that being true. And John Cobs is a huge, huge Jaguar fan, so I know [00:10:00] he would’ve liked to have made the Jaguar faster than the Ferrari, because after all he was a Jaguar dealer in Guilford.

Jon Summers: I just want to touch on that. You talked about how a lot of the lightweights now are not really anything like they were years ago.

I assume that for WPD. The Coombs car might be in that category. ’cause you see it being raced at Goodwood all the time and it presents like a new car. I wonder if you, you are familiar with the cars at Revs, the Briggs Cunningham lightweight E type. Is that as far as you are aware, more like an original lightweight

David Hobbs: E that Briggs Cunningham car got a name.

What’s this type? Is it the EJ two or whatever it’s called, the e something.

Jon Summers: I don’t, I don’t know. I I, I’m just trying to think of what, where would be like an original lightweight E Yeah, that would be a good comparison point. What we are thinking about is, can you look at this Ferrari and say, well, the guys at Jaguar obviously looked at this Ferrari and then made these changes to the Jaguar as a result, and therefore [00:11:00] we need an early lightweight e

David Hobbs: point of comparison.

I think really that the Jaguar we’re trying to, uh. I don’t know about crib, but to try and actually improve the E type by following some of the Ferrari practices, uh, rather than the other way around. I mean, I think the Ferrari was always the quicker of the two cars. Well, ’cause the E type in those days, they didn’t have the material ology that you got today.

These are E type straight sixes. Give over 400 horsepower. Well, when that straight six engine first came out, it gave about 160. So to give four 60 is a massive increase, which obviously you wouldn’t be able to do with the original blocks, crank shafts and main eng, main bearings and that sort of thing. So the only reason they can do that is because of modern materials.

You know, I mean, I don’t know that the in outs and the depths of the. Cos England relationship or the Coombs Jaguar relationship. But I just know that John was a very, and at one stage he was talking about trying to get me in one of his cars. But of [00:12:00] course, Graham was always there. And so that was, uh, unlikely to happen.

But, uh, Coombs was always a very nice chap. Terribly, terribly, terribly, terribly posh. You know, it was a terrible English, terrible. Like myself, who’s rather unc Coth very, very smooth and urban was our

Jon Summers: cobes. You told us that fabulous story a moment ago about, you know, walking past Mr. Barker’s office with the chopped brass.

Yeah. From Jaguar there. Yeah. Let’s imagine our Ferrari arriving at Brown’s Lane here. You know, when BMW buy a Tesla. They strip it down to the component parts and they measure all those component parts to do, you know, we imagine men in in white coats doing that. Is that what Brown’s Lane was like? How many people did Lofty England or did Bill Haynes have?

To be looking at this and what would the process have been like? Would they have driven it around on the streets? Would they have booked Silverstone for a day and driven it down to Silverstone to do that? What do you think that process [00:13:00] would’ve

David Hobbs: looked like? Hard to help you there, but I mean, I worked in the experimental department at Jaguar, which is where all that type of person would’ve been, and there wasn’t very many people in there.

I mean, there’s Mr. Walker who was the foreman. And uh, he was really a farmer. Obviously Bill Hayes would’ve been all over it and people like Mike Kimberly, who was an ex apprentice but was riding rapidly through the ranks and he ran the XJ 13 when I tested it at Myra in 1967. He was still a Jag, but by then he was one of the chief engineers.

And of course she ultimately went to work for Lotus and ran Lotus for many, many years. So people like him would’ve been all over it, like it run, you know, looking at checking everything out. And like all engineers, my dad had terrible issues ’cause my dad was a fruit farmer from Australia. His father had a fruit farm, his grandfather had, it was an orange grove in Adelaide.

And dad was one of nine children, seven of whom were boys. And it was assumed that he would just go into the business, so he didn’t go [00:14:00] to university. But it turned out from a very early age that he was a, a mechanical engineering kind of genius, and he invented that automatic gearbox entirely on his own and started when he was about 19, invented all sorts of mechanical.

Machines ’cause of his day. You know, those early cars back in the, in the mid-teen 19 teens, they were all crash boxes. He didn’t think they were much good for women, so he thought they could probably have an automatic gearbox would be a good idea. So he started working on it when he was about 19 and he had this problem all the time that people would look at his stuff and say, well, Howard, you don’t have a degree in, in mechanical engineering.

Probably don’t know enough about that and I, I can guarantee it. The people like Bill Hayes would’ve looked at that RA and say, oh, well we could have done that, or, or we wouldn’t have done that, or whatever. They would look at it, but they would always be looking at it with slightly jaish eye it, which obviously some of it bought on by, I suppose.

Jealousy. Why didn’t, I think it,

William Ross: [00:15:00] obviously you, you ran your dad’s box in your car. Yeah. What other race cars did you guys try it out in? Or did someone start using it on a continuous basis? I mean, how much success did that have in the racing?

David Hobbs: Well, it had a lot of success, but dad always had the problem of manufacturing, you know, that everybody wanted him to make the gearbox.

They didn’t wanna make it themselves. Ford had a lot of prototypes. We never had the gearbox in any other racing applications except that race where I met Bill France. Jimmy Clark drove my load sleep in the GT rate in the very first, what was now the Rolex 12 hour, which was in those days, the continental three hour, which is what took me to Daytona just a few weeks after I was.

Colin Chapman had called me back in like October and said, could we borrow your car for Jimmy Clark to drive in America? So they borrowed it. They flew in over there, they and Jimmy Clark drove it and he was leading the class by about five minutes. And unfortunately when he came here for a one and only fuel stop, the start had [00:16:00] got Friday and it wouldn’t start when dad’s company finally went belly up at the end of 63.

Which is just over a year and a half later on the floor on the shop floor was a five speed automatic Formula one car for Colin Chapman. So Colin Chapman had certainly tweaked that this was the way to go. Dad had had designed and developed and manufactured a gearbox for him, which never actually got used.

But Dad spent a lot of time also with Jack Braman. Jack Braman came to see Dad on multiple occasions asking to talk to him about putting the automatic in the Formula One car. You know, it, it would’ve been perfect. I mean, obviously now with electronic controls instead of hydraulic, it would’ve been better.

Obviously, you know, things have gone way further than dad had, but he was the first guy to build a four speed automatic transmission. Although, uh, Jim Hall gets the credit for having the first automatic racer. I’m not sure that I didn’t beat him to it in 1959 with mum’s boys up, but I’m sure. That will certainly go [00:17:00] unheralded.

Even if it was the case, we never, we never raced it in anything else.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s go back to the club racing scene. I want to get a better understanding of what that meant because when we look back on the history with our eyes now, we see famous names, Graham Hill, Roy, Salvador, Jack, Sears, as you mentioned, racing in these race.

The caliber of the racing and the British club racing scene. In my mind, I’m thinking when I hear club racing, I think SECA, like grassroots, amateur racing, but you already had these pro drivers in there. Was it a feeder system to something else? Were the pro drivers using it just to make money? Were they using it to jump off to bigger races like LAMA or SPA or something like that?

Kind of tell us about how it worked.

David Hobbs: It certainly wasn’t ever used. I mean, no professional driver ever went back at the club racing. We had a lot of races in England, which would be national races. They would be club racers sort to, but they’d be very high end club racing. Not really club racing. When you got people like Graham Hill, obviously Graham Hill started club racing.

They all did. I mean, Jimmy Clark [00:18:00] started in club racing. I did. Everybody did Sterling mos. Of course there was no go-karting, so you could take that outta the equation and nobody could start until they were 17 in England because you had to have a driving license before you could race a car. Unlike today, where you can race a four in one car when you’re 12 if you got the skill.

Yeah, some of that racing. In England there was, we had a lot of racing in England, which was a, was a very high level and it was basically semi-professional. Now the prize money was obviously negligible. Club racing, had no prize money. Very, very small cups. Trophies.

Jon Summers: You were in Leamington Spa. David, how far would you travel?

Would you travel all the way up to Scotland for a race or,

David Hobbs: well, I never did, but I did go, uh, I think the farthest north I went was Alton Park and the far south I went was Goodwood. I never raced at Castle. Coon raced a lot of Silverson because it was close to home, which is at Leamington Park Race at Mallory Park.

I don’t even know that Mallory Parks exist. Race at Alton Park Ston. Dub that [00:19:00]

Jon Summers: Mallory does say exists. I was there a couple of summers ago watching, uh, motorcycle racing. Oh yeah. Yeah. So got the front end light over the start finish. Yeah.

David Hobbs: I like Mallory Park. Yeah. Had some good race at Mallory. I won a race there.

Load as things had moved on in 1965. I won the, I won the sports car race and load the T 70, which is a bit of a handful around Murray Park. So, I mean, I mean I drove, I drove the Jag and I drove the Morris to and from the races, the elite. We did have a two wheel trailer, but it was an open trailer. It was just a two wheel trailer, and I had a Ford Zephyr to pull it with.

So we had about two spare wheels, maybe a jack and a hammer, and that was sort of about it really. Club racing in America. Now it’s just so bizarrely. Club racing. I mean, everybody comes with a closed trailer and a mechanic and a manager and all sorts of high tech equipment and yeah, everybody got racing tires, obviously.

But it is just a completely different situation to, uh, [00:20:00] the club racing. I started with now club racing in England also has evolved and a modern club racing. I have no idea. I’m, I haven’t been back to England for a club race for. 40 years probably. So I don’t follow it, but I’m sure it also has advanced enormously from my day.

My day was real, real amateur stuff. No driver schools. Jim Ru started the first driver school at Sefton, but he didn’t start that till. The mid sixties, it was very different and it really was club racing. Spent more time in the cafe, in the pub, in the bar after the racing we did.

Crew Chief Eric: Going back to John Coombs for a moment, when he took delivery of the Ferrari, you were already in the States, am I to understand that correctly?

David Hobbs: Probably still there, but. I don’t particularly remember him taking delivery of it. All I know is a grave hill suddenly appeared in it, you know, instead of the lightweight, he’d suddenly eat type.

Crew Chief Eric: So having encountered John and, and you mentioned that he was a bit posh, is there any reasoning behind the white paint that he chose?

Was it to stick out because he [00:21:00] wanted to sell more cars if he raced on Sunday, went on Monday sort of thing? Or was there a reason behind the white?

David Hobbs: No idea. Probably didn’t like it. He used to wear very light gray suits or maybe light gray. But what,

Crew Chief Eric: let’s talk a little bit more about the drivers. I’m sure you’ve got some on your mind, William, that David has already mentioned that we kind of wanna dig into a little bit more that either owned this Ferrari or drove and raced this Ferrari at some point.

William Ross: Well, I mean you get into, you know, obviously with the club racing, but at what point to take that step up, was there something in between club racing and then professional, obviously like, you know, Mike Parks and that, but then you had. Jack Sears stepping up, but then you know, Roy Salvador and that jumping in, I mean, where’s that stuff?

Is it just a big leap from club racing all of a sudden now you’re going against the big guys or how did that kind of progress?

David Hobbs: Absolutely, yeah. I mean, you are racing, club racing and obviously it was a feed of system of sorts beyond drivers. Obviously there were some older drivers, not many, and a lot of people that did club racing had no interest in going any further.

People like me [00:22:00] and Jack Sears and Graham Hill and Jimmy Clark. They had designed on, on going into professional racing, even though there wasn’t much money in it. Really very little money at the time. Well, I think when Jimmy Clark won the World Championship, the first year he won, I think his total take was about a hundred thousand pounds.

You know, now we talk about drivers who are getting two and a half billion dollars a race, but then a hundred thousand pounds back in 1962 was significantly, yeah, would be a lot more than that now. But I mean, yeah, I just won some races and then people started asking me if I would drive for them. In better club race club racers that might have some money attached.

And they would actually ask me how much money I wanted to drive, or they would tell me how much, and I would say, well, how about 50 pounds more? Or whatever. And we’d sort of haggle over of the driving fee, which was pretty low. It’d be somewhere between 25 and a hundred pounds. But also in club racing, when you started to do well.[00:23:00]

Like I did with the elite, the elite became successful, so it became somewhat of a draw. You could go to someone like Clive Worm Layton who ran Mallory Park and you could ring him up and you say, look, I’m wanting to enter the the B-R-S-C-C race. In May. How about some starting money? And they’d say, Ooh, I dunno about that.

People starting money. And you’d say, well, I don’t want much. I didn’t want like a hundred pounds. And you’d finally, you’d settle on about 50 and so you would get some money, but there was no prize money. But there was what we call starting money, you know, appearance, money really is what it was pretty low, but still.

Literally

Jon Summers: just pick up the phone and Yeah. Yeah. And call the track owner and, and say when you were planning the season Yeah. Just to see where you could

David Hobbs: Yeah. Called call the guys at Silverton and try and get some starting money.

Jon Summers: Yeah. Years ago, Orlando C told me that those of you that used to be like roll.

Representatives, or whatever the phrase was when [00:24:00] asking for payment from a TV company or a journalist or something. What he used to do was he and Y and Mass, I think was the other guy used to do it with, they would ask what Sterling asked for and then ask for half of that. Now that gives the impression that everyone talked amongst themselves.

So would you talk with Graham Hill and if Graham Hill was getting a hundred dollars starting money, you might ask for 50 or 75. Was it like that?

David Hobbs: Well, I wouldn’t be talking to Graham Hill ’cause he would been above me, but I’d be talking to other club drivers, people like Chris Ashmore and David Piper and Richard Atwood, you know, people like that.

We were all, where we all started together. Graham was a good bit ahead of me. He is like four or five years ahead of me. You know, I never get my first races when I drove in professional races and I was driving against people like Graham Hill or Jack Sears, Michael Parks, you know, I could find, hardly believe that I was actually in the same race that they were in, you know, where they’d actually talk to me or say something.

You

GROUP: know,

David Hobbs: Graham Hill usually had somebody horrible to say. But other than that, everybody else was fairly nice. So[00:25:00]

Crew Chief Eric: let’s talk a little bit more about Jack Sears. He owned the car for how long? William?

William Ross: Uh, he had it for a long time. 30 years. What does he own? The one car he owned that GTO for a long time, you know, after it kind of, I guess you’d say retired from professional racing, you know, he took it a lot of club racing and stuff.

But Jack owned that car for

Jon Summers: a long time. Oh yeah. After John Coombs had it. Jack’s his, seems to have had it all the way through the 1970s. Oh, did he? There’s quite a lot of photographs of Jack Sears with the car painted red. With it being around, uh, events. I was sort of. Surprise, the number plate is EUP.

And I’ve realized that it appeared in a number of books that I’d looked at and I think I may have even seen it. Uh, shows,

David Hobbs: believe it or not, I’m not really a huge car man. I really only race ’cause I like the racing. I’m very poor on cars. You asked me what model that is. I mean, I’d say I don’t know I’m gonna, but I mean, Jack Sears was a gentleman farmer.

He had a pretty big farm [00:26:00] out in East Anglia, didn’t he? Hell of a driver and a, and a absolutely terrific guy. I mean, he was such a g he was a real GI liked Jack a lot and he was very, very fast. But yeah, I, I didn’t realize, I didn’t realize he owned that car, but I see it’s gonna be an auction down here in Florida and then

William Ross: Yeah, in January at comb.

David Hobbs: Yeah.

William Ross: Yeah. You know, going back in, obviously trying to make the jag make it turn into lightweight to compete with the fraud, besides trying to improve the motor, get more horsepower and making it lighter. Do you know what else they attempted to do or did on that Jag to try and get it more competitive with that Ferrari?

David Hobbs: Not really. I was doing on my own thing, so I, I don’t really know, but I mean I drove that XJ 13, which was gonna be their next big thing. That’s awesome. By that time, Jaar was somewhat constrained by the fact they’ve now become part of British Leland, and of course the guy that ran British Leland, was it the Donald Stokes period?

Yeah. Stokes exactly. S he put the kibosh on the, uh, [00:27:00] XJ 13. He just said, forget it, put it away. Because Richard Atwood and I, I, I drove it four or five times at Myra. Mike Kimberley was the engineer in charge, and Malcolm Sayer, the, you know, the renowned body work guy from Jag was there, and Sir William was there.

Lofty was there, obviously. And a couple of mechanics and we ran it on Sunday morning at six o’clock in the morning in sort of in secret. Ultimately it was exposed. We went to a test day at Silverstone and Richard Atwin and I drove it. It was Richard’s first time in it to give them a, a workless, you know, of what needed to be done.

’cause we were running five or six seconds off things like GT forties. And the reason that Lofty wanted me to test the car and not Norman Jewish, who was the Jaguar test driver. Because by that time I had driven GT forties, lower T seventies and other big engine powerful stuff. So he asked me to drive it.

Norman Dures never quite got over it. He was pissed off to the end of his life that I’d driven the car.

William Ross: What was the potential you [00:28:00] feel for that car? I mean, do you feel with enough work on it, you know, engineering, that that could have been competitive with the GT forties?

David Hobbs: Well, the best thing about it by a country mile was its engine.

It had the twin overhead cam version of the V 12, which back in 1967 was giving 570 horsepower. I mean, it was an incredible engine. In 1967, the car was very ancient. It had the E type type of suspension where the drive shaft is like your bottom link. It had rubber bushings everywhere. It had Dunlop disc brakes, and Dunlop hadn’t made disc brakes for years.

It had like seven inch rims on the back and five inch rims on the front, where now we replicate GT forces, which had got 11 or 12 inch rims on the back and it had an all done up our five race tires on it. So it was very difficult to get a really good feel of how good it was. And of course, that Malcolm Sayer, that swoopy looking body was so fantastic at Lamar back in the fifties when you know you were looking for air, that [00:29:00] you were looking for speed.

Relatively low horsepower, but you know, the days of downforce had started to appear, the lower T 70 dad flaps on the front and they had a, a, uh, spoiler at the back. Just didn’t have any of that. This was very slippery, but probably had horrible lift at speed, front end, lift at speed. I think the car needed a lot.

Richard and I gave them a, a good work list, which would’ve helped obviously decent sized wheels and tires, but made a. You’ve only gotta look at the difference in Formula One between the soft tire and the medium tire for qualifying to see the difference between a 1960s Dunlop R five Treaded Tire, which is like maybe six inches wide and a tire that’s got a slick no, no tread or very, very, those very early slicks.

A bit of tread, a little tiny tread about 12 inches inches wide. I mean, just right there. You, you are looking at four or five seconds.

William Ross: Yeah.

David Hobbs: And then of course, would the car have stood that sort of the chassis when the chassis started to flex badly? Um, when you’re [00:30:00] starting to put the loads and those tires could generate through it.

If you added some sort of spoiler or wing to it. So I don’t know. But the engine would’ve certainly been right on the top of the tree. ’cause the GT fortune when I was driving the GT 40 for golf in 1968, I mean, they were giving about 385 horsepower. With the what? With the heads? The um, Westlake? Yeah. With those heads.

They were giving about 385 horsepower.

William Ross: Out of all the cars that you had the privilege of racing and driving, what was your favorite car?

David Hobbs: Well, I drove so many, it’s hard to tell, but I think the GT 40 was a very special car in its day. I mean, it was great long distance car. The engine, by the time I got round to drive 68, were pretty reliable.

Had that beautiful ZF gearbox, which was terrific. It, uh, was reasonably slippery. It had very little down force, and it was really easy to drive and easy to set up. Small adjustments of roll bars and bit of ride height and maybe a camba, little bit of camba change would make a big [00:31:00] difference. Didn’t get too hot inside, which was great for long distance racing.

Had good visibility and it had no vices. It didn’t have any severe push on certain corners or snap over steer or anything like that, so it, it was a good car to drive. The 9 62, you know, 10 years later was another incredible long distance car. I mean, amazing, reliable as hell. You run a whole thousand kilometer race, then you go to the next thousand kilometer race and run all the practice sessions and on that same engine, then you might put a fresh engine for the race.

You might not. So that was a hell of a car. Single seaters. Probably one of the best cars I ever drove was M 16 at, uh, Indy in 1974. The McLaren, that was a hell of a car, but in some ways the very best car I ever drove was the last McLaren Canam, the M 20, which had been Peter Re’s car in 1972. Then McLaren pulled out because of the Porsche on saw and I drove that car in Carly Black label colors [00:32:00] for uh, Roy Woods in 1973.

And that was a hell of a, I can see why McLaren had won the championship for like five years, six years in a row ’cause it was just slightest touch to a flat change or ride height. Major magic difference. Had incredible traction. One of our best races probably ever was in the, uh, cannon race at Watkins Land in 1973.

I came second to Mark Donahue in the 9 17 30 against which we had absolutely no hope ’cause it had about three, at least 300 awards about, and we did. And I beat all the other nine seventeens. The, with Brian Redmond and Jody Shechter, George Farmer, and a bunch of other, no name has been, never was drivers, you know, like that.

People like Shechter know, obviously. No good at all. To me, that was one of my best ever races. Uh, came second to, uh, Dar

Crew Chief Eric: so to go back to drivers for a second, one of the other folks that drove the white Ferrari that we’ve been talking about. Oh, we’re talking about a white Ferrari. Are we, we were, we were, yeah.

David Hobbs: Carry on. [00:33:00]

Crew Chief Eric: So Roy Salvadori, did you have any interactions with him? Can you tell us anything about him? His personality, his driving?

David Hobbs: Well, Roy was another driver who, who I couldn’t believe I was racing against ’cause there’d been a name for my youth. But of course Roy was really all those guys. The only guy that really, really, really, really, really, really meant it was Stern.

All the others, I mean, Graham, Graham, Hilde, but Sterling was the ultimate professional. I mean, he was the first real professional driver. I mean, he worked out, he didn’t drink much. He didn’t have sex the night before the race, an more that was supposed to do, but he thought he was so sterling was, was the man and, uh, he was the man really to beat.

He, he was the guy that sort of would accept standard. The Roy Sam was obviously incredibly good. Winning Lamont with, uh, Carol Shelby, 1959. I mean, I knew Roy. I didn’t know any of ’em very well, but he was always a bit of a hero of mine. It was very quick.

Crew Chief Eric: So speaking of heroes, and I know this is a soft spot for [00:34:00] John Summers, John being a expert in the history of Mike Hawthorne, was Hawthorne an inspiration for you?

Was he a hero? Did he inspire you to go into racing?

David Hobbs: Well, unfortunately he didn’t because he was up against Sterling. Although he handed to Sterling, he gave Hawthorne. His championship. It hadn’t been for Sterling. Mos Hawthorne would never have won that championship because Hawthorne spun in the Portuguese Grand Prix, which was in downtown Lisbon.

And to rejoin the track, he drove against the traffic and he was disqualified and sterling ever. The gent went to the stewards afterwards. Of course, unlike the stewards today. They listened to driver input. Sterling said, I say chaps, that’s a bit unkind. You know, I mean, the chap had to go back ’cause he had spun the car.

So he, he had to, to rejoin the race. He, he had to go against the traffic, you know, but not for long and didn’t hurt anybody without the way, so they reinstated Hawthorne who won the championship by one [00:35:00] point. If you don’t be for Sterling, you would never won it. Sterling would’ve won it. He’s won and only championship.

But I liked Hawthorne and loved England, loved him. He thought he was the best six to sliced bread because he was. That English gen always wore his bows tie always down the pub having a drink. But I recognized even then that Sterling just had that extra something. Mike didn’t, I mean, not to say that Mike wasn’t a hell of a driver.

I mean, he was an incredible driver, but to me, Sterling was, I mean, I was only like 14 or 15. So Albert Sterling to me was the bee’s needs.

Jon Summers: David, you’ve said a, a couple of things about Lofty, sort of taking a personal shine to you and you just applied there. He sort of took a personal shine to Mike Hawthorn.

I mean, I always felt like Mike Hawthorn was quite a good. Advertisement for Jaguar cars. He was. Do you think Lofty England was thinking like that or literally do you think it was looking back on your relationship with Lofty England, do you think he was just like, this is he’s one of us. I just like the guy [00:36:00] personally.

I can work with him personally. Do you think that’s what it was, or?

David Hobbs: I think he just had a lot of respect for Mike. I do know he was a great fan of Mike, but I’m not quite sure about their relationship other than I don’t know how well he knew him In my case. The only reason he liked me was. I lived in a place called American House, which is halfway between Leviton and Coventry, and I would come out the drive on my motorbike, going to work as an apprentice.

A lofty would go swooping by an E type, so I would race him to work going to, uh, Brown’s Lane. The only thing is when I got there, lofty would be standing arms at Kimba and he’d look at his watch. Ho, I’m supposed to be here at nine o’clock. You are supposed to be here at eight.

But then when I drove the Jag, my dad’s Jag, having rolled it at the first race, I had it repaired by one of the guys in the body shop at Jag. He repaired it at his house in dorm tree in the garden shed at the bottom of his garden. And he [00:37:00] knocked out. We had to get a new hood ’cause the hood had opened on the way home.

And uh, I was with my girlfriend Margaret, who’s in the other room now painting. So I repaired it. Unfortunately, when Joe went to spray repainted, it was duck in blue. By the time he got home from work, it was like a May evening, so it was about seven o’clock by the time he got around to spraying it. So it was a typical English May evening.

The humidity was high, so the car came out. It was a mat car, Matt finish, which today of course is very groovy. But this was a rough mat. This wasn’t as smooth, Matt. This was, this was, and the hood was a real makeshift job. Knocked up the hood out of sort of canvas or something. So he always looked terrible, but as I say, he was often the clerk of the course.

He had saw me at one race, race for DB four and we swapped leads pass, pass, REPA pass, rep pass, and eventually I won the race. He was probably a 10 and a on the club circle at Silver, the club circle as it was. Lofty. He thought I’d done a good job. He said, what I like about you Holmes, is you, you race, you race well.

You [00:38:00] race like you mean it. And he said, I like that. That’s very commendable. And from then on he, he followed my career. So, uh, he became a bit of a fan. So that’s how uh,

Jon Summers: you lofty. What was your bike? So I can pick to you racing him to work.

David Hobbs: When I was 16, my parents bought me a lamb better. Scooter, me and Margaret used to drive around flat out on his scooter.

I go about 55 mile an hour. So I swapped in the board of T Triumph speed twin, which was before the swinging arm. He’d only had a sprung hub, which had suspension without that much, you know, bug roll suspension. And uh, we used to drive around a couple of lunatics on that bike. I love that bike. It was driven so smooth, silky smooth, silky smooth by the horizontal twin engine was terrific.

American police used to have those triumph speed twins and the triumph tiger one hundreds in those days. So, uh, that’s what I like to ride. I wouldn’t wanna write it now, but,

Crew Chief Eric: well gentlemen, I think that’s been an interesting look back into [00:39:00] early 1960s British motorsport. I appreciate David joining us yet again to come on the show and talk to us.

I think we got what we need, right?

GROUP: I think so. Uh, nice to meet you. That’s fantastic. Thank you very much, David. Thank you for your time. Thanks David. I’m sure we’ll meet again.

Crew Chief Eric: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you, David.

GROUP: Alright, thank you Eric.

Crew Chief Eric: We hope you enjoyed another awesome episode of Break Fix Podcasts, brought to you by Grand Tour Motorsports. If you’d like to be a guest on the show or get involved, be sure to follow us on all social media platforms at Grand Touring Motorsports. And if you’d like to learn more about the content of this episode, be sure to check out the follow on article@gtmotorsports.org.

We remain a commercial free and no annual fees organization through our sponsors, but also through the generous support of our fans, families, and friends through Patreon. For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can get [00:40:00] access to more behind the scenes action, additional pit stop, minisodes and other VIP goodies, as well as keeping our team of creators.

Fed on their strict diet of fig Newton’s, Gumby bears, and monster. So consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without you, none of this would be possible.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Special Guest: David Hobbs

- 01:23 Early Racing Days; Apprenticeship and Career Beginnings

- 03:13 Racing Success and Challenges

- 08:30 Club Racing Insights

- 14:59 Technical Innovations and Gearbox Development

- 17:04 Evolution of Club Racing

- 21:11 Exploring the Drivers of the Ferrari 250 GTO

- 21:23 The Journey from Club Racing to Professional Racing

- 22:29 Negotiating Driving Fees and Starting Money

- 25:02 Jack Sears and His Long-Term Ownership of the GTO

- 26:35 The Jaguar XJ13 and Its Untapped Potential

- 30:23 Favorite Cars and Memorable Races

- 33:07 Sterling Moss and Other Racing Legends

- 35:33 Lofty England’s Influence and Personal Stories

- 38:55 Concluding Thoughts and Farewell

Bonus Content

There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.

Central to Hobbs’ early racing was his father’s pioneering four-speed automatic gearbox. Installed in a Lotus Elite, the gearbox offered both automatic and manual override, making it uniquely suited for racing. Hobbs recalls how Colin Chapman borrowed the car for Jim Clark to drive at Daytona in 1962, underscoring the gearbox’s potential. Though the company ultimately folded, the innovation left its mark – years ahead of its time.

Club Racing: Grassroots Yet Star-Studded

British club racing in the 1960s was a curious mix: grassroots in spirit, yet populated by names who would become legends. Graham Hill, Jim Clark, Jack Sears, Roy Salvadori, and Stirling Moss all cut their teeth in these events. Prize money was negligible, but “starting money” or appearance fees kept drivers motivated. Hobbs describes phoning track owners directly to negotiate fees – sometimes as little as £25, sometimes closer to £100.

Unlike today’s polished club racing scene, the era was raw. Cars were often driven to the track, trailers were minimal, and spares consisted of little more than a jack and a hammer. Yet the racing was fiercely competitive, with modified street cars thrilling spectators.

John Coombs, Jaguar dealer and gentleman racer, became a central figure in this landscape. His cars – always painted white – were driven by Graham Hill and others, and when the Jaguar E-Type proved uncompetitive, Coombs turned to Ferrari. The arrival of the 250 GTO (above) shifted the balance, inspiring Jaguar to develop the lightweight E-Type in response.

Hobbs recalls the rivalry vividly: the Ferrari’s V12 and chassis gave it the edge, though Jaguar engineers worked tirelessly to close the gap. Over time, lightweight E-Types evolved far beyond their origins, but in the early 1960s, the GTO remained the benchmark.

After Coombs, the GTO passed into the hands of Jack Sears, as Hobbs puts it “a gentleman farmer and formidable driver.” Sears owned the car for decades, racing it extensively and preserving its legacy. Today, the car, having bared the registration EUP 4 for a time was a fixture at historic events and more importantly – is now up for auction – serves as a living reminder of the era’s glamour and grit.

The Spirit of the Era

For Hobbs, the essence of 1960s club racing was its authenticity. Drivers were amateurs in the truest sense, racing for passion rather than fortune. The paddocks were filled with camaraderie, pub gatherings after races, and the thrill of competing against future world champions.

Looking back, Hobbs acknowledges the Ferrari’s superiority but celebrates the ingenuity, determination, and character of the British racing scene. It was a time when innovation – like his father’s gearbox – could change the game, and when club racing served as the crucible for motorsport legends.