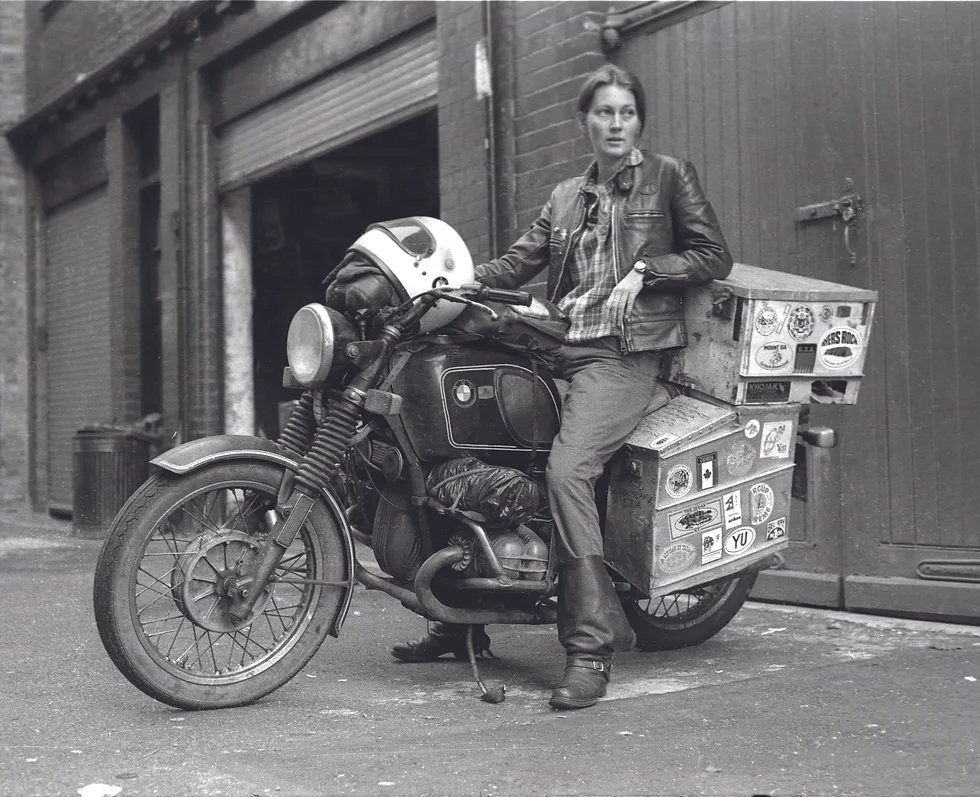

Our guest is a British adventurer and motorcyclist who became one of the first British women to circumnavigate the globe by motorcycle in the early 1980s. Her journey spanned three years and took her across the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, India, and throughout Europe.

Elspeth Beard was just 23 years old when she set out on her journey in 1982. She had recently graduated from architecture school and was feeling lost and disillusioned with her life in London. She decided to take a year off and travel, using her motorcycle as her primary mode of transportation.

As she rode across the world, Elspeth faced countless challenges and obstacles. She dealt with breakdowns, injuries, and illnesses, all while navigating unfamiliar terrain and cultures. But through it all, she persevered, driven by her love of adventure and her desire to prove that women could be just as capable as men when it came to motorcycle travel and she’s here with us on Break/Fix to share her adventure with you!

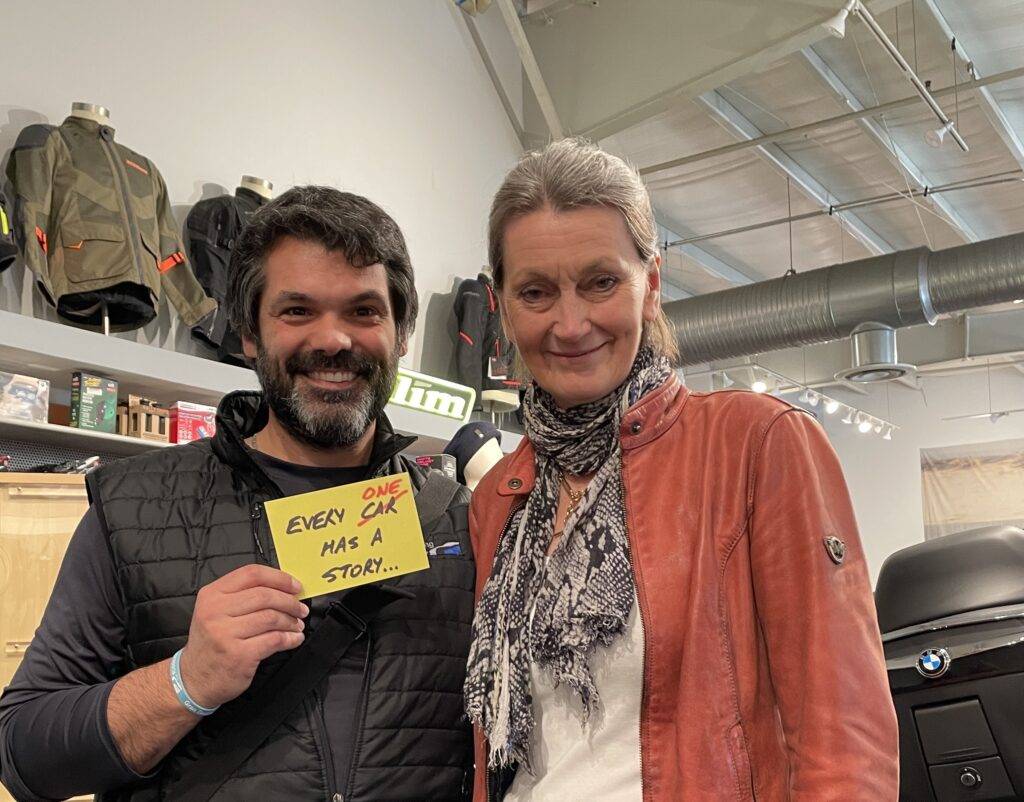

And joining to help add Elspeth’s story to the Break/Fix collection is returning guest Jeff Willis who interviewed Elspeth as part of his new book (hu)man in the machine.

Spotlight

Elspeth Beard - Architect, Motorcyclist, Adventurer for EB Architects

Elspeth Beard the first British woman to circumnavigate the world on a Motorcycle. Elspeth's journey took her 35,000 miles and spanned three years. And she's here to tell it!

Contact: Elspeth Beard at Visit Online!![]()

![]()

![]()

Notes

- How did you get started in Motorcycles? Was there an attraction or just a necessity?

- What was the driving factor or inspiration to embark on a round the world journey?

- Your plan for Survival; as well as Managing Fuel/Speed and Expenses – compromises

- Language Barriers, Discrimination (race & gender), Struggling with Dyslexia – did that make traveling more challenging?

- The BMW wasn’t a common bike in the US compared to other brands, during breakdowns or issues; how did you source parts?

- You seemed to enjoy SE Asia (Thailand, Singapore, etc). Not the biggest fan of India overall? Have you been back? Has your opinion changed?

- Was “Lone Rider” written retrospectively or did you keep a journal of all your events over the 3 years and compile it?

- What did you learn from this adventure, how did it change/mature you as a person? When you look back on it now what are your thoughts/reactions?

and much, much more!

Transcript

[00:00:00] Hello and welcome to the Gran Touring Motor Sports Podcast Break Fix, where we’re always fixing the break into something motor sports related.

Our guest is a British adventurer and motorcyclist who became one of the first British women to circumnavigate the globe by motorcycle in the early 1980s. Her journey spanned three years and took her across the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, India, and throughout Europe. El Beth Beard was just 23 years old when she set out on her journey in 1982.

She had recently graduated from architecture school and was feeling lost and disillusioned with her life in London. She decided to take a year off and travel using her motorcycle as her primary mode of transportation. As she rode across the world, Elsbeth faced countless challenges and obstacles. She dealt with breakdowns, injuries and illnesses, all while navigating unfamiliar terrain and cultures.

But through it all, she persevered, driven by her love of adventure and her [00:01:00] desire to prove that women could be just as capable as men when it came to motorcycle travel. And she’s here with us to share her adventure with you. And joining me to help add Elsa’s story to the Break Fix Collection is returning guest Jeff Willis, who interviewed Elsbeth as part of his new book, human In the Machine.

So with that, let’s welcome both Elsbeth and Jeff to break fix. Thank you for having us. Yeah, thank you very much. Well like all good. Break fix stories. Elsbeth, we wanna talk about your origin, how you got started, especially in motorcycles. Where was the attraction and how you set off on this global journey?

My introduction to motorbikes, I mean, it wasn’t planned or anything like that. None of my family rode motorbikes. My father didn’t, well, it actually started when I was expelled from school when I was 16. and I ended up going to a college in London to finish off my A Levels, which were the sort of exams to get yourself into university.

It was when I was at this college that I met this group of motorcyclists and became friends with them. And [00:02:00] at the time I was cycling around London then and I was getting really, really tired of cycling. So Simon, one of my mates, offered to sell me his little Yamaha YB 100. That was my very first bike.

And in those days in the uk, you didn’t have to take any motorbike test at all. You could buy any bike up to two 50 cc, put L plates on it and off you went. It was brilliant. So that’s exactly what I did. I got myself, my YB 100, Rick and Nick and whatever, taught me to ride up and down my back road or whatever in London.

And then Monday morning I went off to college for the first time on my bike. , but it really was just a cheap and efficient way to get around London. It was no more than that, and I can’t say that When I got on the bike, I thought, wow, this is amazing. You know? And I had no idea that bikes were gonna become such a major part of my life.

It was just transport. And in a London, it was a perfect way to get around. I think after a year of [00:03:00] the a hundred cc, I got a little bit bored with that, so I bought myself a hundred, two 50. And then again, after about a year of that, I got a little bit bored with that. So I bought myself a BMW 600, which was a 60 slash five.

And that’s the one you brought to the United States on your first trip around North America? No, when I bought my 600, my 60 stroke five, that actually was the bike where I thought actually you could go places on this. So it, it was a sudden realization that you could travel on this machine it, so I did my first trip around Scotland on my own, then I went around Ireland, then I went around Europe the following summer.

And then in the summer of 81, I flew out to Los Angeles and I bought myself an old R 75 stroke five. and rode it from the west coast to the east coast, and it was somewhere on that trip riding in the open roads of Arizona or [00:04:00] something. I thought, my goodness, wouldn’t it be amazing if you could ride around the world?

But I never imagined I would. It was just sort of this crazy thought that came in into my mind really that wouldn’t it be amazing if you could, you know, actually ride all the way around the world. So one BMW motorcycle is a purchase, two, uh, you’re beginning to become a fan, but then the third one, now you’re a collector

I know. Well, I do rather like the lbs, I have to say, they’re so easy to work on. If I can service them and I can fix them, and I can strip them down and put them back, then anybody can do it. Really, they are so simple. I love knowing that I can fix my bike anywhere in the world with a basic set of tools. I mean, it’s pretty amazing, especially now when you think to the, you know, motorbikes these days, which are so over technical and got so much electronics in them.

I mean, they’re just a different animal to what it was like. You know, when I did my trip, [00:05:00] and I still now, even today, I like a simple bike when I’m traveling, I still like to know that I can fix it. And we’re gonna talk about the journey and the book here as we go along. I mentioned the third bmw, that’s a 74 R 60 stroke six, which is the one you used on this 35,000 mile adventure.

And then there’s another one after that that gets mentioned that you purchased after you retired. So you’re four BMWs in and I’m sure a couple more after that. I’ve owned a few bikes, yes. . . But I have a question about the stroke six that you rode in the trip and you kept referring to her as she, and in the car community, a lot of us name our vehicles.

So I’m wondering, did the stroke six have a name? It didn’t actually, I used to talk to her all the time, , and I used to encourage her and I used to promise her like oil changes if she got me over the mountain pass or she got me to a certain place without breaking down or whatever. So I [00:06:00] certainly had a very close relationship with my bike.

To me, she was always a she, I dunno why I would call her old girl quite a lot, you know, come on old girl, let’s get up the hill or something. But I never actually had a name for her. So you mentioned turning your own wrenches on these bikes. How did that come about? Was that just out of necessity? Did someone teach you, were you already mechanically inclined before you started messing with the motorcycles?

I wouldn’t say I was mechanically inclined. I mean, my father was a very eccentric psychiatrist, but he was very much Mendon make do. He would always fix everything. And so it was very much part of me when I was a child. You know, he would always have things apart on the kitchen table. As I grew older, I would start to help him to take things apart.

If the washing machine broke down, he’d just take it all apart and I’d help him do it. And I think that took away any fear that I had of taking things apart. You know, to me it was completely normal. If something was broken and had [00:07:00] a problem. You, you know, you just got a screwdriver out and you got the whatever, and you just pulled it apart.

You found out what was wrong with it, and you fixed it. And so I very much had that mentality and I am quite good with my hands and I quite like taking things apart. I used to make, you know, model airplanes and model ships when I was younger. And in 82 when I decided to go on the trip, I realized that in all the countries I was gonna go to, the only person who was gonna be able to fix my bike was me.

I wasn’t gonna find anybody. I mean, in half the countries I went to, certainly after I left, you know, Australia, they hadn’t even seen a BMW motorbike before. So I mean, you were never gonna find a mechanic who was gonna know how to fix it. I bought myself a Haes manual, bought myself tools, the basics, and I just stripped the bike apart before I left because the bike when I left was already seven years old and had 45,000 miles on her when I started the journey.[00:08:00]

She was a reasonably well used bike right at the beginning, so I decided to strip her down and I replaced all the seals and the gaskets and I put new cables on tires back. I mean, anything I could think of that would be worth replacing before I left. And I learned a lot about the bike. And also I had friends of mine who had BMWs and so we kind of learned off each other.

I used to go down to the local bmw, you know, mechanic at the dealership and pick their brains and, and ask them questions if I was stuck on so, so I just learned. But I did know my bike fairly well before I left. The only thing I was absolutely hopeless at and still am, is the electrics. I hate electrics, but the engine, I’m fine.

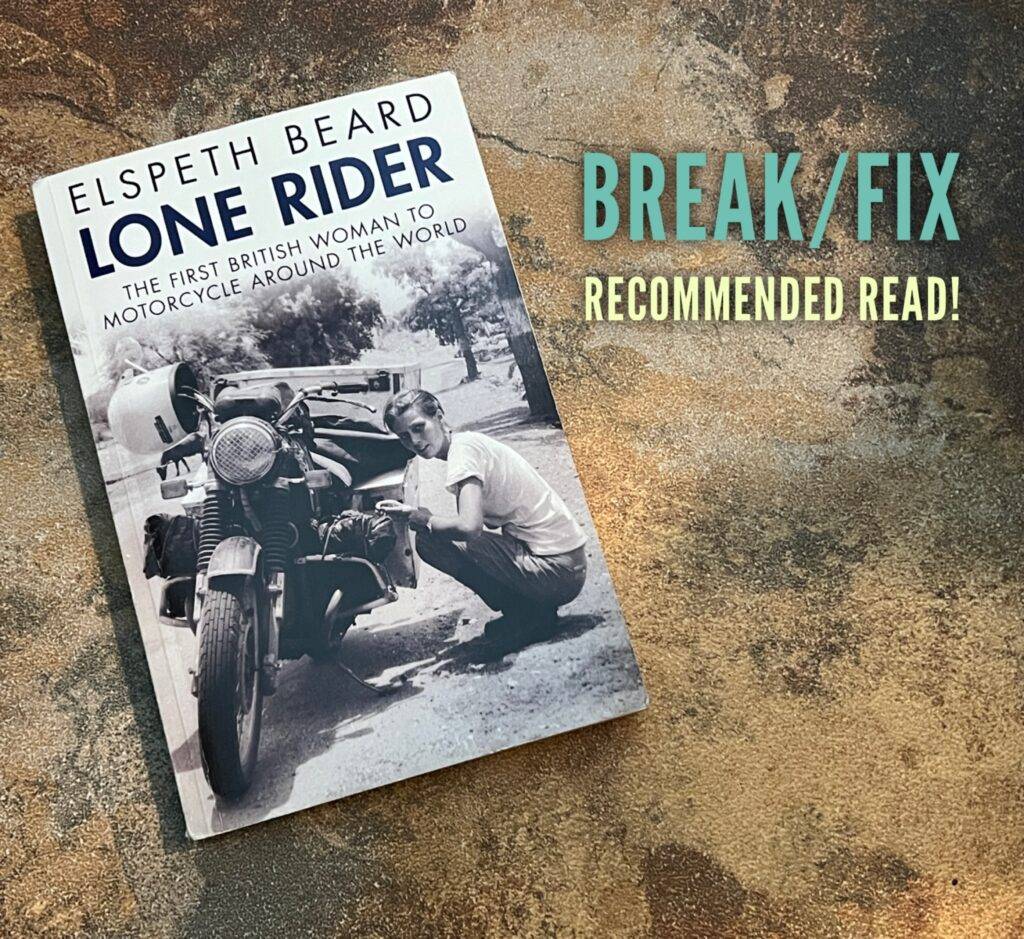

Give me anything with the engine, I can do it. But electrics, that’s a complete mystery to me. Electrics, I prepared myself as, you know, the best that I could. You spoke about preparing for the trip and setting about on the trip and things like that. And one of the, in loan writer, your book [00:09:00] that chronicles the entire adventure is how you set about going on the trip.

Loan writer implies that you sort of just did it almost with no reason and no real planning. But it sounds like there was careful preparation, but I’m still very curious even after reading the book, what was the impetus for just saying, I’m gonna leave home and set about going around the globe? Well, I think I was not at an easy place in my life.

I suppose I’d finished my first three years architectures during my time at university. I met and fell in love with this guy and he sort of finished our relationship about three months before my final. , and so I found it really difficult to work and as a result I ended up with a really bad degree. I was sort of questioning whether I should do architecture at all anymore, whether it was the right thing for me to do, and I was just feeling a bit lost really.

Firstly, it was the whole, what am I going to do with the rest of my life? Secondly, I was feeling really [00:10:00] unhappy, and I suppose it was the sort of escapism in a way. By that stage, I’d been riding bikes for three or four years. I’d had my B M W for a year and a half. I’d done, as I say, the trips in Scotland, Ireland, Europe.

I’d ridden across America the summer beforehand and had had this slightly crazy idea of riding around the world. I just thought, I need some time out. I need to decide what I want to do with my life, and I needed to get away, and so I thought. That’s it. Let’s go. I think that was in the sort of April, may of 1982.

I sort of decided, and then I got myself a job in, in the local pub and I worked behind a bar seven days a week, all weekends, and I managed to save two and a half thousand pounds and that was it. And that’s what I left with. And I knew it wasn’t gonna be enough to get myself all the way around the world, but I just hoped it would be enough to get myself to either New Zealand or Australia where I could work again, earn some more money and worry about it.

I [00:11:00] mean, I think people now, when they plan these trips, because it’s possible to kind of over plan a lot of it, you can sort of plan for months and months and months in advance. It just wasn’t like that then, or I just didn’t approach that trip in that way. I literally, I just did it in stages. And so I had my two and a half thousand pounds.

I had my bike, I’d stripped it down, I’d learned as much. As I could about it. And that was it. And in the October, I shipped my bike to New York, flew myself out there, and then I dealt with riding across America. And then I worried about the next bit, and then I worried about the next bit. I didn’t know whether the trip was gonna take me a year.

I didn’t know it was gonna take me five years. I didn’t know whether I’d be back home in six months, was very much just sort of doing it on a wing and a prayer. I suppose or as the Osage would say, you went on walkabout. There’s no real intention. Well, I knew I was heading west. I knew that much. , there’s obviously undertones of heartbreak.

[00:12:00] There’s this youthful rebellion. Throw on the leather jacket, get on your bike and just go see the world. But there’s another piece that was described in detail in the book, which was Family Life for You. And I didn’t know which adjective to describe it best with. My gut reaction initially was maybe dysfunction, and then it switched to indifference, especially on your return home and how you talked about how you spent time putting your journals together, putting together the scrapbooks and everything.

In the photographs you lamented about people not recognizing how big of an event this was. Not just for you personally, but on a global stage. And so I wanted to just hone in on that for a second and talk about how that also kept you going throughout all this. Was that reluctance to return home? I actually had a very happy childhood and my parents did have a slightly different way of bringing up children to most parents.

I mean, they actually allowed us a huge amount of freedom and they [00:13:00] believed that we should go out and learn from our own mistakes. I honestly think, I can’t remember a crossword from either my mom or my dad and I was quite a pain in the ass when I was , when I was when I was a teenager. I can tell you I was very rebellious at school.

I mean, even when I got it. Spelled from school. They didn’t really say anything. They just kind of took me home and nothing was said. And they just enrolled me in this college in London, and I just kind of carried on cuz they did have this attitude that they shouldn’t have to tell me that that was a stupid thing to do or whatever.

And it was much. More powerful if they just left me to work it out for myself. And so they did have this, what might have came across in the book, a slightly detached, but they were always hovering there and watching, but they never really, or they tried not to interfere, but very much because they did believe very much in letting us go out there and make our [00:14:00] own mistakes.

And I think that was probably partly why I had this slight free-spirited mind. I didn’t actually think that much of going off on my own around the world on a motorbike. I just thought, well that’s what I’m gonna do, you know, cuz that’s what I wanna do. So in a way, their approach and their attitude to our upbringing sort of helped my spirit and my spirit of adventure to go out and do these things.

And although my mom, I mean, it probably was about the only time she did do whatever she could to try and stop me from going. But again, it was never said with a raised voice. It was all just calm. And my father didn’t say anything at all. He didn’t say a word. And I think he was quietly quite proud of what I was trying to do, but he couldn’t actually say very much because he knew that my mom was was so against it.

So it was, I don’t know. It was sort of, family dynamics are always, you know, strange sometimes. Yeah. As you say, when I got back from my trip, they’re sort of [00:15:00] indifference and disinterest. I did find very hurtful, but I think as time goes on and you know, you can kind of look back and you can see things from their perspective a bit more than I could then and now I’m a mother as well.

So obviously I can understand what it must have been for my mom to see me disappearing off on a motorbike cuz she hated motorbikes, absolutely hated motorbikes. You do get a different understanding and perspective as you get older as to why they reacted and dealt with it in the way that they did. I started to theorize that maybe some of that was because you were keeping in contact with your family.

They did come visit you a few times during the trip in India and other places. There were letters being. Throughout the three years. So it’s not like you just vanished like some people do without a trace and then they reappear one day on someone’s doorstep. So maybe in that sense, they still felt connected to you and your return trip home wasn’t the [00:16:00] grand parade that you were expecting.

Yeah, that’s true. I mean, I was actually very good at keeping in contact with them. I mean, certainly in America and New Zealand and Australia, I would phone home every two or three weeks. Which in those days was a real pain in the neck cuz you had to walk for miles to find some phone box in the middle of a, a street somewhere and dial 50 different numbers in to reverse the charges and it was much, much harder work.

So I used to phone home, as I say, every two or three weeks. I mean, after I got to the Far east in India it got a bit more sketchy because it was really hard to find anywhere, you know, to phone from. I was pretty good at writing letters and I had sort of post restaurant places where they could write to.

So I used to pick up mail from my friends and family every two months or something. So I definitely kept in contact with them and I used to send these tapes home. I used to record into these tapes and send these tapes home, and my dad used to transfer them from the micro [00:17:00] cassette onto a standard cassette, and then my mom would listen to them in the car as she drove to work.

So, I mean, she wasn’t completely disinterested and I think a lot of it was her way of sort of dealing with what I was doing. It was almost easier for her to detach herself from it than. Try and immerse herself in what I was doing for her and a mother, and now I was on my own. And a woman. I was 23 years old.

I mean, it must have been incredibly hard for her to not to worry about what I was doing every minute of the day and that all these dreadful things that could possibly happen to me. So I think it was her way of dealing with it, which now I can understand. At the time I couldn’t understand and I was quite hurt by the total lack of disinterest.

Speaking of worrying, I’m kind of curious if you personally ever necessarily worried about much, because as you mentioned, you didn’t have a real solid plan of what to do and where to go, but you did have a very solid [00:18:00] feeling of rebell of independence. But this was also at a time where women were not necessarily thought of as people who could do something like this.

You’re a young, beautiful woman going into some of the most dangerous areas in the world. What were some of the plans for self-defense or survival for other challenges like language barriers, discrimination, including race and gender? Did you have any plans for that or was it something that you just dealt with?

Time by time has worked. I sort of decided right at the beginning that I wasn’t gonna carry a gun or a knife or any weapons at all. I was just not going to do that. And I think one of the advantages that I did have was because, So few women rode motorbikes, especially big bikes. When I was actually on my bike in all my bike gear with my full face helmet on, most people assumed I was male.

Mm-hmm. . So actually, when I was riding the bike, I felt pretty safe. I mean, I was always careful. I never rode after dark. I would [00:19:00] always find somewhere to stay. I, you know, I’d always start, you know, looking at four in the afternoon, five in the afternoon, make sure I was in somewhere in a motel, in a whatever.

Before it was dark. I never wore makeup. I never wore jewelry. I cut all my hair off. I wore the most unattractive clothes, baggy trousers, the most unattractive clothes I could possibly find. So I think if you’re sensible, I mean, I always used to get a sense when I was. Going into a town or a village, if it didn’t feel right, I would just keep going.

If I went into a, a cafe or a restaurant, and again, it didn’t feel right, I became quite sensitive to all of that, and I would always be looking around and watching who was around me, and I would always sit with my back against the wall. If in a restaurant, for example, I mean, it’s very simple things, but it made me feel sort of safe for me.

It was just instinctive to do it because it was trying to protect myself and trying [00:20:00] to minimize the chances of things going wrong. Lots of opportunities where you were. Fortunate to be traveling with other people. Not saying they were there as your bodyguards, but there were adventures with Mark and with Robert and others.

And there were plenty of times where you were in the Outback by yourself as an example, or traveling across the United States on some of the most boring highways you’d ever seen. , if I recall the quote correctly, , there’s some of that too. And Robert especially, I won’t say he was armed, but he carried a knife and things like that.

So if you were in a sticky situation, I do remember one instance in Iraq and Iran where you made the mistake of going out not covered. But then again, in another instance where you were stopped, I believe, was the Indian father that pushed his daughter into the road. You didn’t take your helmet off for fear that someone would know that you were a woman.

So there was a lot of really interesting situations that you had to deal with throughout all this. When I met up with Roberts in India, that transformed the whole journey. I mean, it really did. I mean all the other riding of the bikes, although I met up with Mark in [00:21:00] Indonesia, you know, we traveled on public transport through that.

But certainly all the riding the bike in America, I was on my own. Australia. I mean, I met up with, uh, with Tom and Ewing. We traveled together for four or five days, fortunately, cuz that’s when I had my first accident. So that was lucky I was with them. And then Southeast Asia, I was largely on my own.

India was largely on my own until I met up with Robert traveling with another motorbike. I mean, it was just extraordinary, the difference. I mean, it went from just trying to survive almost every minute of the day, which is what the trip had become to feel like certainly in India to nearly a being a holiday, just having somebody else there.

Robert was a mechanic as well. So it’s only all these fears scratching my head every time my bike broke down, or, not that it did that often, but you know, it was always a worry to me, would I be able to find the problem, would I be able to solve the problem and fix it? And just [00:22:00] having Robert there just made so much difference and it’s company and it’s, you know, it’s just having somebody to talk to and it makes life million times easier traveling with another bike.

You know, if you are ill, for example, you’ve got somebody who can look after you. I mean, I, I remember in parts of India I’d been lying in this. Guest house on a bed somewhere. And I, I mean, I thought I was gonna die and I had nobody to go out and get water for me, get any food for me, nothing. And I was too weak to get up off the bed.

So it’s situations like that, having somebody else there, it is just makes so much difference, a lot, lot easier When I was traveling with other people, but most of the time on, on the bike, I was actually riding alone. Jeff mentioned language barriers for those that have read the book or will read it soon, you begin to realize you’ve struggled your entire life with dyslexia.

And I wondered if that posed an additional more complex challenge of reading street signs and maps and things like that. Was that an imposition for you on the journey as well? [00:23:00] No, it wasn’t actually. I mean, in fact, being dyslexic, because your brain works in a slightly different way, dyslexic tend to be very good at reading plans and maps.

And I’m actually a very good map reader, even though I say so myself, . But I am actually very good at reading maps, which was very useful. So like in Thailand, all assigns would be in like Thai script, but I would see it more as an image or a picture. And I think again, that’s what dyslexic, your brain works, as I say, in a different way.

It’s more on images and. I’m a very visual person. I see things as images, and I actually found being dyslexic more of probably an advantage when I was traveling than a disadvantage. But you don’t know because obviously when you’re dyslexic you only know what it’s like to be. Dyslexic. So I don’t know what it was like if anybody else had been traveling, but um, when it came to communicating with the locals, I was very good at drawing pictures cuz that’s another thing that dyslexic are quite good at doing because where [00:24:00] you can’t do certain things, you know, you’re quite good at other things.

And so I could draw very well. So I used to just draw pictures, you know, if you want food, you put, you know, your hand to your mouth, you want sleep. So it wasn’t difficult. I didn’t really have that much of a problem in managing your fuel and your speed and your expenses, first of all, were there any compromises?

Obviously things are different there as far as passports, work permits, visas, arranging transport from one space to. , how did you deal with the shipping companies? What were the expenses like? How did you deal with the actual money exchange and the fact that the BMW’s not a common bike necessarily at that point in time in the US or overseas compared to other brands when you had breakdowns, how did you source parts?

How did you manage ? There’s an awful lot of questions in there. Sorry. Yeah, so what do you want me to deal with first? The money side of it? Yeah, the money side of it. How did you deal with paying for all these things, and to Jeff’s point, how much did this all cost by the time it was all [00:25:00] said and done?

Yeah, well, that’s a good question. I left with two and a half thousand pounds, and that got me across America to ship my bike from London to New York was 175. And I flew to New York for 99 pounds cuz it was the Freddie Laker era when he was doing all these really cheap flights. And I got across America to ship my bike to New Zealand was really expensive because in those days the main shipping routes went from America to Australia and then my bike would’ve had to have gone from Australia to New Zealand.

So to actually get my bike to New Zealand was really, really expensive. I was paying for it to go all the way to Sydney and then Sydney to New Zealand and then I was gonna have to ship it from New Zealand back to Sydney and I just didn’t have the money to do it. You know, I did have to make tough decisions and compromises because I would’ve loved to have had my motorbike and ride around New Zealand, but I just couldn’t afford it.

So I shipped my bike straight to Sydney and then I [00:26:00] went to New Zealand and I hitchhiked around the country, which is beautiful. I love New Zealand. And when I arrived in Sydney, I had $50 left. That was it. That’s all I had to my name. It was $50. Fortunately, I had friends in Sydney. I slept on the floor for about a month while I managed to get some work.

I got a job as an architect’s assistant. I’d like to call that one an unpaid internship. Well, the first one was unpaid internship. It was indeed . That’s a whole nother story. But then I did get paid. I went to another architectural practice and I worked there for about four months, and they did pay me, and I got a job in a pub in North Sydney as well.

So I was working pretty much all day and all evening and all weekends, trying to save as much money as I could. So I was in Sydney for seven months. When I left Sydney, I had managed to save $6,000 us, I think it was. The $6,000 got me home and I [00:27:00] arrived back in London with the thousand left over. So it was 5,000 from Sydney to London.

I suppose I understood that part of the 6,000 was lost during a robbery somewhere between Southeast Asia and India. So I kept wondering how did you make the money back? Did you make money along the way? No, it was, yes. So when I was in Singapore, I had all my money stolen, but I carried it in American Express Travelers checks, so I got it all back.

Oh wow. Ah, I have to say American Express were brilliant. They really were. Because we had everything stolen a whole lot. I mean, I had a bit of cash stolen, but most of the bulk of my money was in the travelers checks, and I was good. I kept all the numbers and I kept all the, so I, I knew exactly what numbers had been stolen, and so they just replaced them all outside of the unpaid internship in Australia.

At one point, it almost seemed like you didn’t wanna leave. You were reluctant to leave Australia. You kept making [00:28:00] excuses and procrastinating, especially on your departure, which was a reoccurring theme throughout the trip. It felt to me like you fell in love with Australia and. You almost were gonna stay there, or am I wrong in that assertion?

No, I think that’s very true. I did in the various places where I kind of settled down for a bit. I mean, not a, I mean there weren’t many. I did find it quite hard sometimes to move on. You know, the road was a cold, lonely place sometimes, and when you’ve got the comforts of someone’s home or you’ve made yourself a little home somewhere, it’s hard to leave all that and push yourself out again.

I often say to people that one of the hardest things. On the trip was actually leaving the first time, you know, making the step, taking that big step to actually leave for the first time. And I think when you get settled in places around the world, it’s going through the same process again. You have to readjust your mind into thinking you’re gonna be on the road again, and you’re gonna have to [00:29:00] look after this and do this and live in a certain way.

And it just took time to make myself actually go. But again, once I was on the road, I was fine. But it’s just that step, you know, of leaving. But I did enjoy Sydney. I, I, you know, I loved Australia and I made lots of friends in Sydney and it was really home from home in a way. , you know, and it was quite daunting going out again, having been in one place for seven months and made all these friends, and suddenly you are out on your own, on the open road, on your bike.

Again, having to look after yourself and do everything yourself. It wasn’t easy sometimes. So Jeff alluded to probably one of the most ironically, comical parts of loan rider, which is the visas, passports, and work permits. At some parts, the way you described the bureaucracy of different governments and embassies was just off the charts.

Oh, I know, because you couldn’t really plan that far ahead. And I also didn’t really know what countries I was gonna be going to [00:30:00] next. I mean, I really didn’t plan very much beyond the next country because things changed a lot. And sometimes you’d have to change route or you couldn’t go to that country.

You’d have to go to another country. I mean, for example, when I was in Northern Thailand, You know, I planned to go through Burma to get to India. Well, all the road orders were closed. No, you can’t go through, you’re not allowed. So I had to turn around and, and ride 1500 miles back all through Thailand, all the way down to Malaysia to catch a boat across to India.

So you have to be very adaptable and very flexible and be prepared to just change just like that. And you just get used to thinking like that. So the visas, I would just get the visas literally for the next country I was going to. And then when I was in that country, I’d get the visas for the next country and I’d work out sort of where I was gonna go or which route I thought I would try and get on.

I certainly trying to get a visa for, oh yes, that’s right. The work visa for Australia. That was a absolutely. Versus the tourist visa, which is a whole [00:31:00] nother thing. Well, no, first when I tried to get a work visa, because I knew I was gonna be working in Sydney, I was pretty sure that’s where I was gonna, I mean, I, I kind of decided halfway across America or something that Sydney, I’d be able to earn more money there than I would in New Zealand.

And I was pretty confident I could get to Sydney on my funds that I. I think I went into about four or five Australian high commissions all across America and they kept saying either affiliate forms and anyway, they kept saying, no, no, no, no, no. Then when I got to Los Angeles, I thought, you know, I was getting kind of closer and closer to Sydney and then I said, well all don’t give me a work visa, just give me a tourist visa.

And they said, no, no, no, we can’t give you tourist visa now cuz we know you don’t have any money and we know you’re gonna have to work there. And I went, ah, . So anyway, I shipped my bike to Sydney anyway. And thought I’ll get to New Zealand. And I got to New Zealand and I went to the Australian High Commission in Auckland.

I mean, it was just such [00:32:00] luck. I mean, I walked into this head guy or whatever and I was wearing my leather jacket and he said, oh, he said, are you a biker? And I went, well, actually, yes I am. And so we had this whole thing about what I was trying to do and I said, well, I’m trying to ride my bike around the world and I wanna work in Sydney.

And so he said, give me your passport. And I handed it over and he just opened the page and stamped my work visa and gave it to me, and that was it. You know? So it was just such luck. It’s those moments where it’s just meeting the right person at a particular time that can completely change your fortunes.

You know, everything of the whole trip. It’s just meeting that one person who can change everything for you. Not only that, but it speaks volumes to the vehicle enthusiast community in general, where we’re willing to help each other out, whether it’s. On the racetrack or on an adventure or something like this.

I’ve always found that petrolheads as a general expression for all of us motorcyclists and car enthusiasts alike, we tend to roll up our sleeves and help our brethren and sistern out when we’re in trouble. [00:33:00] It’s just something about this community. I know it exists in others, but not in the same way.

There always seems to be these limitations, whereas when it’s dealing with transport it, it opens up in a different way for all of us. I think that’s very true. I do think it’s particular with, you know, motorcyclists. So I don’t know. I think it’s just different with motorcyclists. We do look after each other and we do help each other out.

I think that’s very true. So El Beth, you seemed to have enjoyed Southeast Asia with Thailand and Singapore, et cetera. Obviously not the biggest fan of India for good reason. , have you been. To India and has your opinion changed? I mean, I vowed when I finally got out of the country, I would never set foot in that country again.

I did go back to India actually, but I was asked to be a general manager of around the World Motorcycle tour, taking 23 motorcyclists around the world in 2003. And as part of the tour, of course, we had to go to India. I did return to [00:34:00] India, but we did the kind of southern part of India, which is a lot more sort of chilled out and easygoing.

I mean, I think when I was there the first time, I went from right up to Calcutta and then the whole sort of industrial belt, which goes from Calcutta to deli. I mean, it’s the most populated, it’s the most, it’s just. And I think that’s the bit that I traveled through most of the time. I mean, when I managed to escape and I got into Stan where it’s very sparsely populated, and then y’all went up to lay LADA again, very, I mean, I loved it there, but it was just the multitude of people.

I mean, I never felt in danger and I never felt threatened in India. It was just the curiosity of the people. And I think being a woman, you know, they’d never seen a BMW before, certainly never seen a BMW with this huge aluminum contraption O on the back. And then when I took my helmet off, and it was a woman, I mean, it was just, they were kind of just blew their minds.

And so I did attract an [00:35:00] awful lot of attention in India and it did become quite exhausting for me. You know, it really did. I imagine just being a reader, reading some of those things, I. Felt for you in the moment, . Unbelievable. Besides the negative experiences, where were some of the most positive experiences of the whole place?

Like what really is indelible in your mind? I mean, India is a fascinating country. I mean, it really is extraordinary. I mean, the color, the buildings, the temples, the forts that, I mean, it’s an extraordinary country. It really is. But again, you see, when I started to travel with Robert in India, it got a hundred times easier because all of a sudden when we stopped and we had 50 people around us, it didn’t kind of matter so much because we had each other we could talk to or look at.

And it’s very different from when you’re completely on on your own, especially a woman on your own and you’re surrounded by 50 men, just much harder to deal with. But with Robert, it was much, much easier. I [00:36:00] mean, it does have some, as I say, stunning scenery, beautiful buildings, amazing temples. It’s a very colorful country, but.

you do need to be quite strong mentally to travel through it. Certainly on a motorbike, certainly 40 years ago, , I’m sure it’s different now. I’m sure it’s easier now or better or whatever, but it was hard work. Plus the fact it was very hot. It was about 45 degrees, cuz I got there during the hot season and I got very ill in India.

I got distant tree, I got hepatitis, you know? So I was really, really ill and it makes you very weak. And I’d been on the road then for a year and a half, so I was tired, you know, my bike was tired every day was a constant challenge, just kind of fixing something just to keep her going. It was just hard work.

Do any of the illnesses or maladies or the accidents that you’ve had, do they still kind of haunt you? No. When I got back I was ill for about a year. I had a lot of. Problems with my guts and whatever for a year, and I went [00:37:00] to the School of Tropical Medicine and were in London and I did all these tests and they found all these parasites and stuff inside me, but I’m fine now.

When I hit the dog in Thailand and broke my toe, that still gives me a little bit of gyn . But apart from that, I can’t complain. I can’t complain. , your memories are obviously very strong and you can recall all of these things. Very easy. Was this something where, , while you were on your trip, you had an idea that you were going to write loan writer, and was it being written as you were traveling or was this written more as a retrospective?

No, I mean, I had no intention to write a book at all. Absolutely not. But for some bizarre reason, I did keep everything and I don’t know why I did it. So once I’d ridden across America, I would package all my shipping documents, my insurance. My, any bits of paperwork, my speeding tickets, , all these bits of paperwork, I [00:38:00] would package them all up and I would send them home.

And I was quite good at taking pictures as well. You know, I was quite a keen photographer. Take pictures. And then as a say, when I got to the end of each sort of section or each leg of the journey, I would get the prints developed. I would send the prints home first. And once I’d heard the prints arrive, I then I, I sent the negatives.

Separately. So I would hope at least I’d have a 50 50 chance of one of them arriving and then I kept all the letters that my parents and friends had written me. And all this was incredibly useful. When I came to write my book, cuz I wrote my book 35 years after I got back. It was like a year long process just going through all my document because my parents kept all my letters, I kept all their letters.

I wrote a sort of fairly sketchy di. I mean I wrote a diary off and on really. I then had all my tapes cuz my dad had kept all my micro cassette tapes. So I had all of those to use. I took about two and a half thousand photographs throughout the whole trip. So I had quite a lot. I didn’t do [00:39:00] it thinking I was gonna write a book, but I just had this sense that it was important to keep a record of everything.

I have no idea why. No idea. After I left Australia, I actually wrote down all my petrol purchases. again, I haven’t got a clue why. Mm-hmm. , so where I bought the petrol, how much I’ve put in, and how much it costs me. And the exchange rate so you can work out Exactly. And actually at the back of my book, there’s a whole table of all my petrol expenses.

Mm-hmm. , which is a slightly bizarre thing to do, but a lot of the time, I mean, I was on my own a lot. If you’re spending an evening alone in a tent from five o’clock onwards, you know, there isn’t really a lot to do . And so I would just to keep all these records, I used to keep a record of where I stayed every single night.

I used to check my money, so count my money, how exactly, how much money I had left. I mean, I was slightly obsessional with my money because I, I was so determined I was not going to ask my parents for help [00:40:00] because they hadn’t really been that encouraging. I was absolutely determined I was gonna do this and I was gonna do it on my own and I was not gonna ask them for help.

I used to check my money twice a week. So I’d count my money and I’d sit, work out exactly how much I’d spent in the last like three days. and if there was like 50 cents that I couldn’t account for, I mean it would really bother me and I would have to work out exactly where I’d spent this 50 cents. But I didn’t have a lot else to to do , so it kept me occupied.

So I wonder if the gas receipts was as a result of the fact that your Speedo cable broke when you were in Australia and maybe you were using that to figure out how far you traveled or how far you could travel, you kind of reverse calculating it. Yep. There was that as well. I think I did manage to replace this.

Speedo cable somewhere in Southeast Asia. I think I got a Speedo cable in Kuala Lumpur, if I remember. And I dunno how I got it. I can’t remember , but I did manage to replace it. So then it was working again. But also, you know, [00:41:00] the time that you have inside your helmet, I mean, it was hours and hours and hours and you know, you have to occupy your mind.

something. And so I was constantly working out, you know, mileage per gallon and this, and I, and then I tried at all different speeds and how much difference that made, and then I calculate it all again. And it was something to give me, something to think about when I was, you know, so I have to say this, for those that are listening to this that haven’t read the book yet, you might be thinking, oh, this reads like a history textbook,

And it doesn’t, it’s not full of facts and figures and dates and names and things like that. It is a love story. It is a struggle. It is a journal. It’s all things wrapped up into one. And then there’s this just pleasant, dry British humor interlaced throughout every chapter, especially quotes. You know, that rock that John Wayne fought over, you know, things like these, these weird little quips that I picked on throughout the book that just make you [00:42:00] smile and make you chuckle as you transition to the next thought.

So for those that are interested in reading it, I highly recommended it does not read like a bunch of gas receipts and shipping labels. Yeah, yeah, yeah. No, sorry, I didn’t mean, yeah, yeah, absolutely. Right. It’s just that the information is there at the back of the book, should you be interested in it . But what it does conjure is the question about what you really learned from this adventure, how it changed you as a person, how you matured.

When you look back on it now 40 years later, what are your thoughts? What are your reactions to some of the things that you wrote yourself in your own journals and on the micro cassettes and things like that? You know, writing the book was a whole nother journey in itself, which was a very unexpected journey, to be honest with you, because I did my trip and then I got back and I really struggled when I got back.

I have to say, I got very depressed. I found it really hard to readjust. Nobody understood what I had done. Nobody [00:43:00] wanted to listen to what I’d done for the last few years of my life. There was no interest and so I very much sort of packed everything away and it was a sort of portion of my life that I just put in a cardboard box.

It was in a cupboard, and that’s really where it stayed for 35 years. and then I got on with the rest of my life. So I went back to uni. I finished off my architecture. I then bought a Victorian water tower. I spent seven years converting that into my home. I did lots of other trips. I traveled to South America, Africa.

I got my pilot’s license. So my life just really just moved on, and I can honestly say in 20 years or 25 years, I don’t think I thought about my trip once. At all. I just carried on with my life and it was really going back and looking at my diaries and reading my diaries and listening to my tapes. That was the weirdest thing because I’d never listened to them.

It’s like time travel. Yeah. Why would I listen to them when I came home? So I never, I’d never listened to [00:44:00] them. So I was listening to myself, a 23 year old in the Outback in Australia, and my bike has just caught fire. It was really bizarre. Did you ever say to yourself, listening to yourself, what an idiot I was, or was it more rose colored glasses?

No, it wasn’t actually. I actually sounded very, very posh. I sounded a bit like the queen, and . And I got a very high voice and I, but when my bike caught fire, I was almost just kind of laughing about it. I was like, oh yeah, my bike’s just caught fire. Ha ha, ha, ha. What am I gonna do about this? Oh, my g I was so kind of, I don’t know, kind of chilled and relaxed about stuff, which I’m sure I wouldn’t be now.

But then I was, and in many ways I didn’t recognize it was like listening to another person. It really was. It was very strange. My book is very open and very honest about a lot of the things that happened to me during the journey, and I think a lot of people have been quite surprised that I have been.

[00:45:00] as open and honest as I have about certain things. You know, it was that detachment, that fact that 35 years had gone by, that I was sort of able to write the book as if I was writing about somebody else, in a way. But anyway, going back to your first question about how it changed me and, and actually writing the book, it made me realize.

that the bike trip was a very pivotal time of my life and it sent me off in a direction that the rest of my life took. Once you’ve been out on the road and looking after yourself and dealing with all the problems that I had to deal with on my own, you really do realize, or I certainly felt that there wasn’t anything I couldn’t deal with or tackle.

I mean, it really was life changing. I mean, after I came back from my trip and then I did my architecture, and then I bought the water tower and the water tower I had to buy without planning and consent and whatever, and everybody said, you’ll never get consent. You’ll never, I mean, the council said, well, never.

[00:46:00] And I just remember thinking, yes, I. I’ll just do it because I’ve done all this. I can do anything and nothing was a problem. And I don’t see things as problems. I just see them as things to overcome and things to get through. And I think that’s something I learned from my trip that there really isn’t anything you can’t solve.

There isn’t a problem that can’t be solved if you are determined and you believe, and that’s the other thing, you have to totally. And. Utterly believe in what you’re doing is right. 100%. You can’t even have a, a little chink of doubt. You’ve got to Absolutely. When I was doing the tower, I mean, the fact the tower should be converted into a house.

I mean, I was just, so, this is the only thing this building can be, you know, used for. I just didn’t give up every obstacle that was put in my path, I just dealt with it, got rid of it. Next one got rid of it, next one. And after a year and a half of that, I finally got the approvals. And they, everybody said, you’ll never do it.

And just like everybody said, you’ll never ride around the [00:47:00] world. And, but if you want something enough and you’re determined enough to do it, you can do it. And that’s what I learned and that’s why now I don’t have any fear of taking anything on or, I mean, I’m a bit of a bull in a China shop sometimes, , I’m, but you know, I think you have to be like that if you want something enough.

Would you ever do the trip again? No. . Why not ? Well, I wouldn’t do the same trip again or something similar because there wouldn’t be any point, but certainly wouldn’t do it again. Now, I think traveling now is so, so different and I’m so glad I got to travel before technology had taken over our lives. It really was venturing out into the unknown.

Certainly when I started the trip in America, I’d try and plan like two or three days ahead. You know, I’ll stay here tonight and then there the next night and it’s 300 miles and I’ll do there the next. And by the time I got to India, literally if I managed to get to the end of the road as far as I could see it.

That was [00:48:00] good. That was it. I just literally planned 20 minutes ahead, half an hour ahead. It was just, everything was instant, that moment, and you just lived every day like that. And you can’t really do that anymore. Mm. Because there’s just too much information, too much, you know, you can plan things too much now.

So I’m really glad that I did the trip when I did. I always think of those from about 75 to about 85, I think was the golden years for traveling , because it’s when bikes or cars, they had reached a stage where they weren’t gonna break down every week. You could actually rely on them. The riding gear was reasonably good.

It wasn’t brilliant, but it was okay. and the world was still there to be explored. There was no technology to, so it really was the golden age. Yeah. And that’s the period of time that’s usually romanticized by the backpack, the bottle of wine and a, a baguette and some bri. And that’s how you traveled the world with $50 in your pocket.

And, and it’s very true. And those days, to your point, are [00:49:00] long gone. You can over plan everything. A GPS is gonna get you out of a bind versus you had to figure it out. I don’t know where I am. We’re just gonna ride until we see something familiar and then deviate from there. You did mention something before about all the naysayers, all the people that said you couldn’t do what you wanted to set out to do.

And there was one in particular, uh, Mr. David Calderwood. I put him up as your number one rival. That was the tipping point that pushed you over that said, you know what the heck with all of you, I am gonna do this and I prove you wrong. The book didn’t come full circle on your relationship with Mr.

Calderwood, and I wondered if. You ever wrote to him again if he ever reached out to you, and what his thoughts were on the success of your journey? Well, interestingly, I’ve never met him, but it was after my book was published. If anything had happened before my book was published, I would’ve put it in it, but it didn’t.

So after my book was published, I did various. Interviews and whatever. And there was one in interview I did with somebody in America, it was a [00:50:00] long time ago, I can’t remember. And I sent him the copy of the letter that Dave Calderwood had written me. It’s incredibly condescending, chauvinistic letter

Anyway, he put it up on the internet. So the letter was winging its way around the internet for quite a few years. And obviously somebody had told Dave Calderwood that this letter was up on the internet. . He actually contacted me on Facebook Messenger and he said, oh, hi. You know, um, apparently I wrote a letter to you in the early 1980s, but I don’t remember it.

Um, but if I did, then I’m sorry, , that’s all I got. I’m roundabout, sorry. I know I will take that as a win. There’s a lot embedded in that very short statement, so Yeah, there is. Exactly. And I only waited 35 years, so there you go. . There’s another part of this book, and I mentioned it before, is the romance part of this entire journey.

And there’s three major characters in the book, not necessarily characters cuz they’re real people and there’s Alex [00:51:00] who kind of set things into motion. Mark, who is riddled throughout the entire chronology. And then Robert who ends it. For those that have read the book, we all know how Robert’s story ends and I won’t go there, but I do wanna highlight.

Mark and Alex just a little bit, cuz Mark is the father of your son, Tom, and then Alex seems to just pop up and disappear out of nowhere. Does he still do that? He still pops up and disappears? Yes. , I saw him . I saw him about six weeks ago actually. He just phone me up. He said, oh, I’m just passing. Can I have a cup of tea or something?

I went, oh yeah, fine. Ok. So he popped up and then we had a cup of tea and we had a very nice. And then he vanished off again and I haven’t heard from him again. Probably hop up again in another year or something. And what of Mark? Tom now is 32. So the need for his parents to stay in contact as obviously as needed as it was when he was younger.

I mean, we get on. Okay. I mean, he’s got another family now [00:52:00] and so he’s got his own life. I mean, it’s 30 years ago so it’s, you know, we’ve both moved on on our way, but you know, we’re civil to each other. But yeah, it’s fine. Are you still in contact with Robert’s family or his brother Herbert or anybody else?

No. Well unfortunately his father had died already, so when I came back and we came back through Europe and I stayed with him before I, I rode to London, we stayed with his mother. So his father had already died I think when he was younger. Mother died obviously quite a long time ago. Herbert’s brother, I haven’t been in contact, but I am in contact actually with some of you know, Robert’s friends.

Motorcycling and, and friends of Roberts who I am in contact with. I think I’ve touched on this. When we originally spoke, when I was interviewing you for my book, if some young person, whether it’s a young lady or or what have you, came up to you and said, I really wanna ride my bike around the world, just like you’ve said to many others on your start of your journey, what would you say to that person?

Oh, I would say absolutely do [00:53:00] it. I mean, no hesitation at all. , the best thing I ever did. Really, it was the best thing I ever, ever did. Even with the way things are so different now and all of the challenges, yeah, but you know, you, you have to do these things in the moment that you have. I’m sure there were people riding bikes and doing long trips in the, in 1930s.

and they probably look at my trip and they think, well, why would you bother? You know, you’ve got decent roads, , you’ve got bikes that work all the time, and it’s boring. So you know, we all just have to do it in the time that we’re here. It’s not the same, but still an amazing world out there to see and explore.

And I mean, I would say switch off the gps. . That is one thing I would say to them. Don’t try and over plan and switch off the gps and just go out there and get lost and explore and don’t get into this trap of planning every minute of every day. Mm-hmm. , which isn’t easy to do because it’s there. I mean, I went to Mexico early last year and a, a friend [00:54:00] lent me a bike and I thought, right, I’m gonna do this the old school way and I’m not gonna use a gps and I’m just gonna have maps and I’m not gonna book any, and actually you couldn’t kind of do it because when you arrived anywhere, all the hotels have been booked out.

Oh yeah. Because everybody books everything ahead weeks and weeks and weeks ahead. So you arrive in places and there’s nowhere to stay. So unless you book, like everybody else is booking a few days ahead, you get places and there’s nowhere to stay. See, what I heard there is she’s not willing to camp out anymore.

I’m not willing to. Damn right. I’m not . There’s one thing I refuse to do. I’m too old to to be in a bloody tent, I tell you. Ugh, not for me. Do you still ride and do you have a, a big trip planned? What’s your next adventure? I do. I still ride. I was actually doing a trip in Tajikistan last. May. Wow. And unfortunately, I fell off and broke my ankle, which wasn’t very clever.

Oh, no, no, it wasn’t good. So I’m still doing trips. I’m actually [00:55:00] coming over out to America. I’m visiting a few dealerships in Virginia, Mary Land, and then I’m flying up to Minneapolis and then Chicago and then home. So you mentioned visiting the United States and some dealerships. Does that mean you’re still a BMW fan, rider and collector?

I wouldn’t say collector, obviously. I’ve still got my old R 60 strike six. My trustee, my trustee, R 60, which I still ride. She’s still roadworthy and I still ride her. And then I’ve got my R 80 Gs basic, which it’s in 1998, so what’s that? 20 odd four years old. I think of her as my modern bike . And I know she isn’t, but I suppose if you stick with what you know and you know, I can service them all, I can fix them all.

I don’t trust anybody else really to work on them. I like to work on them myself. And then I, I’ve actually been invited because this year, you may or may not know, it’s the hundredth anniversary of BMW this year. That’s [00:56:00] right. And they’re having a huge party in Berlin, which I’ve been invited to. All right.

And they’ve put this big poster together, which is a collage of about 10 photographs of important people in the BMW’s history. Cool. awesome. They actually used the black and white iconic picture, which is amazing. Very cool. Anyway, so that’s. July? I think so. Yeah. It’s good. It’s good. I did actually buy a new BMW and I didn’t like it at all.

Which We won’t. Um, I dunno. It was just so boring. It was almost too good. Yeah. Didn’t have any of the old quirks. It, it had no personality. No character. No personality. It was like a sewing machine. It was just really boring. . I owned it for two months and sold it. What about your son? Does he ride? Is he a BMW guy?

No. Well, he has got a bmw actually. I taught him to ride a motorbike first when he was 17 and he got his bike license before [00:57:00] his car license. But then he got a car and then it all got a bit cold and wet for him. And so he doesn’t really ride very much. And then he became a father. I became a grandmother.

Ah-huh. Last year. Congratulations. Thank you. So he doesn’t really ride very much anymore, but he’s. Still got his BMW in the garage, but I don’t think it’s been out for like two years or probably more. What does he think of his mom’s great adventure? I don’t know really. He doesn’t really say very much. I think he’s very proud of me.

I think. I mean, he has actually read the book, which was probably not easy for him. Kind of it is what it is. , maybe it, it may, it helped him understand me a bit more. It, you know, I did find motherhood quite challenging. You know, maybe, I don’t know, wasn’t around as much as I possibly should have been. I did what I could, you know, we always do the best we can.

Mm-hmm. and it wasn’t easy. The circumstances of, you know, with my father dying and, and the water tower and Mark and, you know, I had a lot of other stuff going on [00:58:00] and, well, I’d like to hope he’s proud of me. I’m sure he is. . So, one last little question. Ellizabeth, do you still live in the water tower? Oh, I do indeed.

I do indeed. Absolutely. Absolutely. That’s awesome. I’ll probably live there until I’m crawling up the stairs on my hands and knee in my nineties. No, actually it’s really good. It keeps you incredibly fed. You know, you don’t have to do any exercise. I never go to the gym and nothing. I don’t do anything. I just live in the Watertown.

I’ve got 90 stairs up to my kitchen. Wow. So I’m up and down those stairs five, six times a day. And I remember I had like a, you know, a nanny, an a Perga who came to look after Tom when he was about three and she was about 15 stone when she arrived. A year later she was down to 10 stone was living in the tower.

And then I saw her a year after she left and she was 15 stone again, . That’s awesome. And, and it’s just taking exercise without thinking about it. That’s what I like about it. You just live there. It keeps [00:59:00] you fit and slim and it’s brilliant. Well, Elizabeth, this has been a pleasure and I want to give you the opportunity to mention any shoutouts, promotions or anything else that we haven’t covered thus far.

Well, really o only my book, which you’ve already mentioned, which is called Lone Rider. I’ve also got a photographic book, which I published last year, which I compiled about nearly 500 photographs of my trip, which is a sort of coffee table book and that you can buy on my website, which is www.elfabeard.com.

Nice and easy. ELs Beth’s journey was groundbreaking in many ways. Not only was she one of the first women to undertake such a trip, , but she also did it at a time when the world was much less connected than it is today. She relied on paper maps and guidebook and often had to navigate without the aid of GPS or cell phone.

In the end, ELs SP’s journey took her 35,000 miles and spanned three years, but more than that, it changed her [01:00:00] life and profound ways. She returned to England with a renewed sense of purpose and a new found appreciation for the world around her. Today she is recognized as a pioneer of motorcycle travel and an inspiration to women everywhere.

To learn more about ELs Smith, be sure to pick up a copy of her award-winning book Loan Writer, which is available in print and via Audible on amazon.com. You can also check out her website. El beard.com or follow her on social media at Elbe dot Beard on Facebook and at Elbe Beard on Instagram. I cannot thank you both enough for coming on here, Jeff, for introducing me to El Smith and her story Elsbeth, for coming on the show and being an inspiration to women around the world for being part of the Petrolhead community and continuing to just share this story with everybody.

It is absolutely incredible, and I think it’s just one of the gems in the motorsports and vehicle enthusiast community that more people should know about. I, I’m just in awe of what you did, even [01:01:00] though it was so many years ago. It’s still an incredible and fascinating story, so thank you. Thank you. Thank you very much.

Thanks a lot. Yeah, a pleasure. Thank you. Okay. Alright. Bye-bye. Bye-Bye. Bye.

If you like what you’ve heard and want to learn more about gtm, be sure to check us out on www.gt motorsports.org. You can also find us on Instagram at Grand Tour Motorsports. Also, if you want to get involved or have suggestions for future shows, you can call our text at (202) 630-1770 or send us an email at crew chief gt motorsports.org.

We’d love to hear from you. Hey everybody, crew Chief Eric here. We really hope you enjoyed this episode of Break Fix, and we wanted to remind you that G T M remains a no annual fees organization, and our goal is to continue to bring you quality episodes like this one at no charge. As a loyal listener, please consider subscribing to our Patreon for [01:02:00] bonus and behind the scenes content, extra goodies and GTM swag.

For as little as $2 and 50 cents a month, you can keep our developers, writers, editors, casters, and other volunteers fed on their strict diet of Fig Newton’s, gummy bears and Monster. Consider signing up for Patreon today at www.patreon.com/gt motorsports. And remember, without fans, supporters, and members like you, none of this would be possible.

Learn More

Consider becoming a GTM Patreon Supporter and get behind the scenes content and schwag!

Do you like what you've seen, heard and read? - Don't forget, GTM is fueled by volunteers and remains a no-annual-fee organization, but we still need help to pay to keep the lights on... For as little as $2.50/month you can help us keep the momentum going so we can continue to record, write, edit and broadcast your favorite content. Support GTM today! or make a One Time Donation.

If you enjoyed this episode, please go to Apple Podcasts and leave us a review. That would help us beat the algorithms and help spread the enthusiasm to others by way of Break/Fix and GTM. Subscribe to Break/Fix using your favorite Podcast App:

Elspeth’s journey was groundbreaking in many ways. Not only was she one of the first women to undertake such a trip, but she also did it at a time when the world was much less connected than it is today. She relied on paper maps and guidebooks, and often had to navigate without the aid of GPS or cell phones (because they didn’t exist, yet!).

In the end, Elspeth’s journey took her 35,000 miles and spanned three years. But more than that, it changed her life in profound ways. She returned to England with a renewed sense of purpose and a newfound appreciation for the world around her. Today, she is recognized as a pioneer of motorcycle travel and an inspiration to women everywhere.