Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Break Fix podcast is all about capturing the living history of people from all over the autos sphere, from wrench, turners, and racers to artists, authors, designers, and everything in between. Our goal is to inspire a new generation of Petrolhead that wonder. How did they get that job or become that person?

The Road to Success is paved by all of us because everyone has a story.

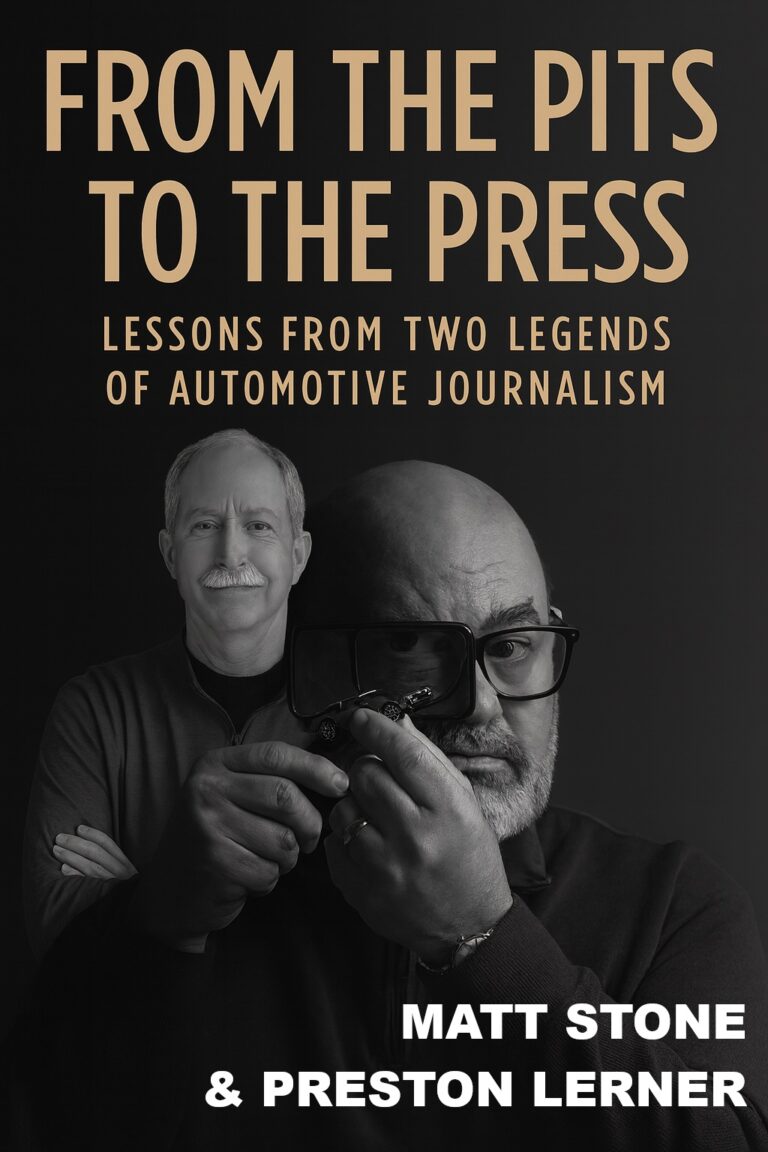

Crew Chief Eric: Welcome to a very special reunion episode of Break Fix Podcast, where automotive journalism meets memory lane. Today we’re bringing together two of the industry’s most respected voices, Matt Stone and Preston Lerner for a conversation that’s equal parts insightful, nostalgic, and full throttle fun with decades of experience.

Between them, Matt and Preston have chronicled some of the most iconic moments, machines and personalities and car culture. From glossy magazine pages to bestselling books. Their stories have shaped how we see the automotive world so tune [00:01:00] in as they reflect on their journeys, trade tales from the road, and share what still gets their engines revving today.

Joining us tonight is returning co-host Don Weiberg from Garage Style Magazine, one of the many personalities on the Motoring Podcast Network. Welcome back, Don.

Don Weberg: Thank you, Eric. How are you this evening?

Crew Chief Eric: I’m good. And with that, let’s welcome Preston and Matt to break fix. Nice to be here. Great to be here, Eric.

Yeah, just

Matt Stone: what he said.

Crew Chief Eric: All right, guys. This episode’s gonna be a little different than our Normal Road to Success. Tell me your life story. You know, were you a petrolhead since you were a kid? This comes to us by way of the I-M-R-R-C because as a lot of our fans know, we do remastering of content from them as part of our history of Motorsports series.

And I came across this wonderful little DVD four gt, how Ford silenced the critics and humbled Ferrari and conquered Lamonts by Preston Lerner. And inside this insightful DVD Preston talks about working with Matt Stone, and I’m like, wait, wait, hold on a second. What a small world we live in, especially the automotive world.

So I wanted to talk about. How did you guys meet? [00:02:00] And let’s just start from there.

Matt Stone: I have one remembrance of meeting press. The first time was at a book signing for his extremely definitive and seminal book about the entire scarab scene, the race cars, the street cars, LANs Rev Low, the whole scarab thing.

Now a lot of you out there will not know what a scarab is other than a a dung beetle, but a fabulous breed of American born and built race cars. That are just fabulous and gorgeous and fast and noisy and all that. Nobody had ever written much truth to power about Revit Low and his effort and the guys who drove for him and where the cars went and blah, blah, blah, and Preston decided here’s a story to be told proper, and he did it.

I have this book. I think, again, if my house was on fire, that would be one of the books that would go out the door with me because it’s so well done on such an interesting story. And it was a book signing, I believe, at the Auto books in Burbank. And he was the guy behind the table with the [00:03:00] pen. And I bought the book.

And I don’t have the pen, but I have the book and I have Preston as my pal.

Crew Chief Eric: So Preston, is that how you remember the story going, or,

Preston Lerner: uh, well, not exactly. Funny thing is, is you never know what you’re gonna have behind you in your bookcase. Only by coincidence. I have Matt’s Irock book over here, right to my left.

It’s just sitting there. I wrote the SC book, and that was really a great experience. It was wonderful to meet all those people from the early Sports Card days of the fifties and then into the Formula One into the sixties. But I remember Matt was, we were both freelancers at the time, and I swear, Matt, you’re pretty sure you wrote an escape road, as I recall what it was called wasn’t the Auto Week would do the one Pagers.

Matt Stone: It was the one page per issue. Classic car section.

Preston Lerner: Yeah. And you did one on the scab as I recall.

Matt Stone: Okay. It’s coming back to me now. Yeah.

Preston Lerner: That’s my recollection of when we met. We talked about the scabs, I believe. Then I don’t even remember doing a book signing at Auto Books for the scab.

Matt Stone: Well, maybe we just met there and I got your book and you signed it for me.

I don’t remember could, but I have very distinct memories of you and I together the first time at Auto Books. Although we’ve met up there many, many, many more times over a lot of other books. But I knew it was [00:04:00] scarab related for sure. So we’re going back a few years yet. Yeah,

Preston Lerner: that’s 91. 90, 91.

Matt Stone: Now, was that 1890 or 91?

Preston Lerner: It was one. Dinosaurs, Rome the Earth, that’s for sure. But okay. Long time ago, but of course I lived in Burbank and Matt at the time was in Glendale, so we were neighbors as well. And we would run into each other periodically at various events.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, since we’re on that subject, Preston, why don’t you bring the audience up to speed on a little bit of your cv.

What magazines did you write for as a journalist?

Preston Lerner: So I started as a newspaper reporter in Dallas. I was at the store Telegram, and then the uh, morning news never wrote for the Times Herald started freelancing for various magazines, moved up to California and I was originally doing stuff for Sports Court International and Road and Track Specials, which was, it was a whole division back then.

It was incredible. They would put out 13 issues a year, as I recall. It was as big as the monthly magazine, but eventually I caught on with Automobile Magazine, which was still a going concern at the time. Thanks to Jean. She was then Jean Linde mood, but later Jean Jennings. That’s who I did most of my, uh, car riding for was for automobile.

You know, Matt [00:05:00] actually ended up over at MotorTrend. So at the time we were competitors. Eventually we were under the same corporate ownership, but that was further down the road.

Crew Chief Eric: So what was it like, you know, you knew Matt, you met Matt, now you’re competitors in the world of journalism. What is that like?

So Matt, from your perspective, and maybe tell us a little bit about your journalism fame outside of MotorTrend and how it overlapped with Preston’s, but how did you guys feel as competitors?

Matt Stone: From what I said, I mean it, it was a totally friendly competition. I mean, we all competed for the same exclusive stories and the most juiciest drive or most juiciest interview.

Certainly between Preston and I, only friendly competition. But I would have to say our bosses. Maybe not always because they were competing for the same newsstand buyer and the same magazine dollar and the same advertiser dollars. So it was very competitive. And it was kind of funny because Road and Track and Car and Driver were under the same ownership for a while as was automobile and MotorTrend.

We had in-house competitors and we had down the road competitors. And like I said, person to person, it was more often than not very friendly. If somebody from a competing magazine [00:06:00] called and needed some help, I’d help ’em. And I would like to say that there were few times I made that same call that they helped me, but again, for advertising dollars, newsstand dollars, and you know, those killer cover stories, it was pretty competitive.

Preston Lerner: It was pretty collegial I thought, but I was not on staff. So Matt was on staff and he had to deal with the advertisers and he had to deal with corporate. Um, for me, I just would go out and do stories that were assigned to me or, you know. Or that I pitched in.

Crew Chief Eric: So speaking of Rodent Track, this is the post John Bond period, right?

So this is whole new management. Totally different regime, right?

Preston Lerner: It was a different regime, but it was still, it was Matt Lorenzo was doing it then, and it was, Matt may remember better than not, but I still think it was the same. It was before it was bought by Hearst and when they fired everybody and they moved to To Ann Arbor?

Matt Stone: Yeah, it was, it was Matt De Lorenzo and John Dinkle. Oh, right. Yeah. Ron Sessions was running the specials. That’s the guy that I worked for when you were working for him too. That was a lot of fun.

Preston Lerner: Yeah, that was great.

Matt Stone: Yeah, that was way down the highway from John and Elaine Bond and the much more modern times.

And that company was bought and sold. I don’t know, CBS owned [00:07:00] them and somebody else owned them and then somebody else owned them again and, and then most recently they turned over their editorial and management staff, 48 different directions. Nobody that I really still know there or do any work for.

Preston Lerner: The road track specials, which Ron Sessions ran at.

Andy Bhop was the second in command. Andy was a, is a great guy and they put out 13 one shots a year. So they did two new cars issues and they did two new trucks issues and they did like a sports and GT car issue and, but I do remember like Road and Track had an amazing library back then. They were in, uh, Newport Beach at the time was before they moved in Arbor, they had a librarian which is like incredible, a full-time librarian.

Otis Meyer. Yep. And when I wrote that SC book, they allowed me to use a bunch of their photos free and I was able to just go through their archive, which was incredible. They had just rolls and rolls and rolls of undeveloped film, of just stuff. It was all archived and you could find stuff, but they didn’t print any, the unprinted stuff out for me.

I mean they had all the press kits and everything. It was really incredible. And I mean, I don’t know how they did it putting out between the monthly and this specialist 25 issues a year. Those were the fat days of print [00:08:00] journalism, that’s for sure.

Crew Chief Eric: That brings up a really good question about the daily grind.

As an automotive journalist,

Preston Lerner: my experience was somewhat different ’cause I wasn’t on staff, so I only worked on specific stories that typically. About half of them that I pitched and half of them that were assigned to me and kind of at automobile, I became, for lack of anybody else there, kind of their racing experts.

So when they wanted to do a racing story, I usually did ’em. I didn’t do as many of the press trips for new car launches. I typically didn’t get assigned to those. I did some of them and they were fun, but for me it was, it was kind of a different experience. And I was also freelancing for other magazines, non-car magazines as well.

So. My experience is a little different than someone who would be on staff, although Matt was a freelancer for many years before going on staff, but I guess he would’ve a better perspective kind of from the two different viewpoints.

Matt Stone: You know, generally it was a lot of fun. I mean, there were some fabulous days.

There were a lot of great and good days and a few tough days, but it was a lot of fun because you’re surrounded by working with guys and gals that love cars and love to drive and love to do all that kind of stuff. I was sort of the cultural imperative and history guy, so when it was something to do with history, [00:09:00] cultural imperative, personalities, whatever, that was a lot of in my bucket, and that’s where I got to meet a guy named Don Weiberg.

Uh oh. I am happy to say these 4,000 years later, we are still friends and like I said, some of the days were really fun and some of the days were just long and some were long and fun. One of the things that I so enjoyed is when we would go out on a staff road test, okay, we’re gonna take these four cars and we’re gonna go to New Mexico and shoot a feature and do a a road test.

And we’d sit around every night at dinner and talk about how we felt about driving this car and that car, Hey, the seats on that one as good as this one or whatever. And the dinner conversation was a blast. Everybody came from a different perspective and of course has different physicality and different tastes in how they like to drive front, drive, rear drive, all drive, VH, turbos, whatever

Crew Chief Eric: Matt’s words painted this imaginary picture of what we all see on a top gear special.

Is there any truth to those, you know, behind the scenes when you see like a top gear [00:10:00] special and they’ve gone out and they’ve tested the cars and you see the crews and they’re sitting at dinner. I mean, is it very much like that or is that more dramatized? The life that you led as a journalist,

Don Weberg: Eric, I bring to your table of lesson Met Stone teach me long time ago.

We admit to nothing when the recording devices don’t work. You’ll live in mystery.

Matt Stone: I’ll answer that a little more. What the top gear guys have created is quite amazing, and those guys are all personalities and, and I have respect for them and affection for them. That’s a little spiced up.

Crew Chief Eric: Okay? That

Matt Stone: doesn’t mean it’s lies.

Or untruthful, but it is definitely seasoned for tv. I enjoyed going out on the road trip with the guys and gals. That was a lot of fun, a lot of work, long days, but it was really, to me, one of the sweet spots of doing this kind of work was bonding with a great team, and I had those most years, not every year or all the time, but most years.

Really good teams. We worked hard and we had a blast and we did photo shoots until [00:11:00] dark and plus hopefully put it all together in a good story when we got back. That was very satisfying.

Don Weberg: Eric, now you see why I’ve always spoken kind of highly of Matt Stone, having worked for him, having been his whipping boy.

He was fun to work for. He really was. He was never short of words. He would always had an opinion about something, but he was always really, really good at guiding you when you asked kind of questions, when you had straight up ideas. He had a a really great way of guiding you. And I’ll tell you, I remember a couple of those.

I mean, I never took the New Mexico vacations or anything like that with you guys, boondoggles. Yeah. But I do remember a couple of long road trips where they were stuck with me because they needed a body to drive the vehicle to the location. And a couple of those were with Matt.

Preston Lerner: Yeah, I gotta say, I would only occasionally get called in for some of the campos.

You know, you get four or five cars and needed. Like Don was saying, you needed bodies, you know, even if you weren’t gonna be writing the story, you needed somebody to drive the cars, get ’em from A to B and B2C, and so on. And I found those to be the longest assignments because photography had to be [00:12:00] done either very early or very late.

’cause they wanted the golden light. And really the stories were driven by photography. I mean, because the photographer only had one bite at the apple. So the photographers needed to get what they needed to get and they needed to get it whenever they needed to get it. And even though as a writer, you know, even when you were writing the story, and a lot of times I wasn’t writing the story, you’d think, oh, you spent all this time driving the car and getting dynamic feedback and, and so on and so forth.

And no, you were mostly standing around waiting for the photographer to take interiors and, and do beauty shots. And for the high speeds thing, that would rig the suction cup card of the camera. It was going two miles an hour. It looks like it’s going 180. So I found those to be a little tiresome. To be honest.

They were long days. I like going out on feature stories. I was by myself occasionally. I had a photographer with me and I sort of set my own agenda. That was a lot more pleasant for me.

Don Weberg: I do remember Matt a couple of times watching you work with the other senior editors, including the man in the corner office, and I remember it was always impressive.

They always kinda look to you.

Matt Stone: Something I never understood, by the way.

Don Weberg: Right. You were just playing it. Right. You were just going with it. You know? They want my opinion. I’ll give it [00:13:00] to ’em. I was doing my thing. Yeah, it was always fun working with you. It really was. Except for that time, he slapped me across the face, but I guess I deserved it.

Crew Chief Eric: Okay then. Now that is a Jeremy Clark’s moment.

Matt Stone: We worked hard and learned a lot and went great and marvelous places, and made many, many friends all over this world. I mean.

Crew Chief Eric: And I’ve heard Matt say it a bunch of times before, there’s a difference between a writer and a journalist. So I want you guys to expand upon that for our audience,

Matt Stone: and this is no knock on you, tiktoks and Facebookers and all, well, maybe it’s 40 characters and a crappy photo is not great journalism.

In my humble opinion. It may or may not even be journalism. I mean, I guess if you got the one photo of somebody very, very important, running naked down through Times Square, maybe that’s journalism.

Crew Chief Eric: So when I was a kid, they called those tabloids. I just wanna throw that out there, what you described, right?

Social media and all that. Content

Matt Stone: creator.

Crew Chief Eric: Yeah, content creators, tabloids.

Matt Stone: But there’s no analysis in that. It’s, it’s a [00:14:00] crappy photo in 40 characters. I never have, nor do I now want anything to do with that scene. I don’t do that stuff. Good luck to those who do. And if you make money good on you, and you have fun and you’re providing good content.

I love that you have to be a content creator. Now, you used to be able to be a writer or a journalist, and now you have to be a content creator.

Preston Lerner: Well, I’m not sure there’s really, uh, a tremendous difference. I mean, I, I kind of came to the game through newspapers. I didn’t come through it as a car lover first, so I think I brought a little bit more of that kind of granular stuff to it.

The thing is, is marginalism was a thing you really needed expertise in cars. More than journalism. I mean, if you weren’t, if you didn’t know cars, you could be a great journalist, but you know, you didn’t know the nitty gritty about how cars worked and how they were supposed to handle and perform. You were kind of worthless, I think.

I think you needed to really have both skills needed to be there.

Matt Stone: I would agree with that. I would say that not every writer is a great journalist, and not every journalist is a great writer, but there are poets. Poets can be fabulous writers. They may not know or understand the [00:15:00] tenets. Journalist. The ideal quinella is when both of them meet in the middle in one individual with a singular writing voice and a singular mind that really understands the job, the topic, the story, and the results, and then really knows how to put it down in writing.

And that guy’s name is Preston Lerner, as far as I’m concerned,

Crew Chief Eric: in the world of automotive journalism, the goat, that’s the greatest of all time. Is that still Brock Yates or is there somebody else that you guys look up to and say? He was one of the greatest automotive writers of all time.

Matt Stone: Brock Yates, the assassin,

Preston Lerner: just finished a manuscript for a book on racing from 64 to 73 pro racing.

And so I. Went through all the literature magazines back in the day, and I gotta say, Yates was unbelievable. He was the most opinionated. If you agree with him, he was the best. If you disagree with him, you’d probably want to kill him. But I think he was probably the most influential journalist I know. He went beyond journalism, you know, cannonball stuff and safety and I mean, he was on TV as a broadcaster.

I never really thought about who would be the goat, but I think he was the biggest name, best known outside of the field. I mean, he wrote novels. [00:16:00] He was really something. I didn’t know him very well, unfortunately. ’cause I never worked for Car And Driver was never back in the Michigan area. I’d say he would be the first one that comes to mind.

Matt Stone: Yeah, and he absolutely had the chops. He had the chops and the receipts. Could I conclusively? Undoubtedly unequivocally name, name him the goat. I’d have to think longer and harder. But with Preston, he was right up there. Right up there. I knew him late in his life. What a fascinating guy to sit and talk with.

Yeah.

Crew Chief Eric: What do you, would you say Matt is the key differentiator between a writer and a journalist?

Matt Stone: They, again, can be the same person and can be acting. In a duality, but the tenets of journalism about, you know, corroborating evidence and doing good reporting and all of the stuff that goes with journalism, that’s something not every writer understands.

You know, in terms of attribution, of information, of quoting, of credits, of backup, of second sources, of all the things that make a great journalist may or may not have anything to do with being a great writer. Ideally, you want both

Preston Lerner: using [00:17:00] automobile as a, an example, David E. Davis, PJ O’Rourke, gene, I mean.

They weren’t really journalists. I mean, they weren’t out there interviewing engineers and typically their reporters notebooks, like I was, you know, laying down specs. And that wasn’t their job. I mean, they were there to reflect their larger than life personalities and tell great narratives, and, and they were great writers.

You know, they had stuff that I couldn’t do. I mean, no one was gonna mistake me for David e and, and when you were at a dinner, I mean, David e and Gene would just hold court. Matt too. That’s not what, what I was, but the skills are somewhat different, but they’re not antithetical. I think, like Matt said, if you could do both of ’em, that’s better and better.

Crew Chief Eric: So Preston, would you say then, for writers that are listening to this right now, we’re just gonna use that term to not split hairs. If you’re in the realm of non-fiction, do you think the transition to journalism is a little easier than a straight fiction writer? Or to Matt’s point, a poet or somebody that’s writing prose?

Preston Lerner: I mean, I think it’s pretty straightforward. I mean, if you’re doing a piece where you need to do real reporting, I mean there, there is some experience you need or expertise and, but I think it’s pretty easy to, you know, you ask people questions that you’re, you’re all of a sudden, you’re a journalist, you’re a reporter.

I think you can [00:18:00] learn that on the job. You know, the point is, sometimes I, I feel like when you watch, you know, the influencers, I mean, they’re not asking questions. Their stock and trade is their own opinion. That’s not what a journalist is. A journalist is not out there to give your opinion. You’re out there to get what other people have to say about a subject, sort of pass that information along.

So I think you can certainly do it, but I, a lot of people, they rather talk about their own opinions than they would get somebody else’s opinions. That I find a little off-putting sometimes. But you know, I’m a little bit old school that way.

Crew Chief Eric: And we could probably debate the difference when we bring in historians into this as well.

Or we’re recounting facts and figures just like as journalists would, but it’s in more academic, you know, those kinds of things. But we’ll put a pin in that for now. So, Don, do you wanna weigh in here? As we transition?

Don Weberg: I want to take you boys back to New Mexico and some of those road trips where we grind the hell outta the Audis and wonder if the Mercedes will survive.

What were some of the more memorable stories, the more memorable assignments that you worked on, either together or separately, that still stand out in your head today?

Matt Stone: It’s a great question, Don. I can name a [00:19:00] couple from my own experience and I’m sure press has his too. Something we did at MotorTrend every year was a annual top speed shootout and we would go to a proving ground in Arizona on New Mexico that had a five mile banked oval Indianapolis motor speed bay, but twice the size.

And we would bring a race driver de jour with us to take whatever car that was and ring them out to VM Max. On this five mile track, we had Justin Bell one time, Danica Patrick one time, and one I particularly remember who was the ice? Cool, wonderful professional, Brian Herda. Oh, and we, and we brought big weapons that time.

We had the four gt, the first one, the five four supercharge V eight, and we had a Porsche Carrera gt the V 10. I’m trying to remember at the minute what the third one was, but we had that strata of cars. We’re having a little meeting before, you know, photographers are snapping around a little and the test equipment [00:20:00] guys are rigging up cars.

And so Herta comes to me, he says, top speed, right? I said, yep. He says, you know, it could take me one or two laps to get to that. Take all the time you need. We’re looking for the biggest number you can ring out of this car and stay in one piece. Boy, if he didn’t do it too, Brian was the coolest guy, an extremely competent racing driver.

He got in every car, and I think all three cars, if I remember, cracked 200 that day. And for a street streetcar granted of an exotic, very high, powerful one, that was impressive. And, and we have the pictures and the timing slips to prove it. Danica Patrick also did a very good job for us. She drove extremely professionally and listened to us and gave great feedback of what the car was doing in a corner, banked at whatever angle and mean.

She was a complete pro and did a wonderful job. But those events were wonderful. Sometimes we had three or four cars, sometimes we’d bring 10. Another one I particularly remember, of course, uh, Preston and I have many of the same heroes, but one in particular, [00:21:00] and this was my idea for a story, is, uh, Mario Andretti used to have a winery in Napa.

And there were a whole bunch of great hot convertibles that had just roadsters and spiders that had come out about the same time. The Mercedes SL 55 A-M-G-A-V 12, Aston Martin DB seven, the BMWZ eight. So we thought, you know, let’s just bring those things up to Napa, take pictures and we’ll have Mario drive them, make him the road tester, putting Mario Andretti in a race car and saying, tell us about this race car that’s not new ground to evaluate high performance and exotic cars on the street.

Okay, Mario, we’re out here driving in the backyards of Napa. What are you feeling? And I’m gonna tell you, I’ll never forget that day, the last sign up in my brain when I die. We’ll be thinking about that story and spending two days with him out just driving and talking. I’m pleased to say that he’s still my hero.

He’s become my friend. I’ll never forget that one. Anytime soon. There were others. But I’ve talked [00:22:00] enough. Preston,

Preston Lerner: I’m curious, was that before the Newman book or after the Newman book? Before. Cool. That’s

Matt Stone: great.

Preston Lerner: So back in again, the days when there were really elaborate press trips, Chrysler was doing a deal for, um, the second gen Viper had just come out.

Remember the GTS coop with the blue with the white stripes?

Crew Chief Eric: You mean second generation Daytona Coop. That’s my favorite. Viper. I love that car.

Preston Lerner: Tom Kaki was the, uh, legendary PR guy for Chrysler at the time. Put together this trip where we went with these vipers. We went to the berg ring, we went to spa and we went to Ram, or Reem, or however you pronounce it, in France.

The plan was to go then to drive from France. We were supposed to go to the Arctic Reon and all these vipers would be there at the Arctic Reon. But it was really as incredible. So along for this trip to give like presentations at night where Phil Hill and Jesse Alexander. So it was really cool. I knew Phil Little and Jesse was a friend, and that was great.

At any rate, what happened was the leg of the trip was like three days or something. We were going to the Arctic Dream. I was paired up with Phil for some reason. I don’t know why. I mean, Phil Hill is like a, you know, a hero and I’m mostly asking him questions and he’s talking, you know, I’m asking about various races and this and that.

I’m supposed to be doing [00:23:00] the navigating. Well, I wasn’t paying any attention to the navigating, and I got us totally lost. So we’re supposed to be at the York Triumph at a certain hour and we’re nowhere close to there. We’re lost in the middle of Paris and Phil had this reputation, justifiably for being very high strung.

He was going insane because we were lost in Paris. You know, we were supposed to be at this thing. And I was like, you are Phil Hill. Who cares? You know, we don’t need to be there. We, we’ve got our own Viper, you know, we made to the York Triumph after they’d done the big photo shoot and we missed it. And Phil was peeing the whole time at me, but I got a great story about, it’s why I really didn’t care.

And like I had Phil to myself for like two and a half hours or whatever it was,

Don Weberg: in a Viper GTS.

Preston Lerner: It was cool. And Phil was driving. I was just. Navigating or not navigating it. Again, those are the kind of press trips. I don’t think they do anymore. I mean, it was like a three or four days. And I mean, they didn’t even need to sell the viper to the media.

Everyone in the media loved that car anyway, right? Mm-hmm. But that was, that was a great thrill. I mean, I, there’s so many, when you ask the question, so many pinch me moments that I’ve had mm-hmm. Through this field. I mean, I’m just, I feel lucky to have been able to do what I’ve been able to do, and I never would’ve been able to do it otherwise.

So just have to thank the powers that be for letting me have these opportunities.

Matt Stone: [00:24:00] Preston is a very competent, road racer, good racing driver. But when you ride with Phil Hill, Mario Andretti. Any of those drivers that any of us have ever ridden with, you realize what a crap slow driver you are. I mean, it’s uncanny.

These folks have talents in their fingernails that you can’t dream of. They’re just talking and driving like it’s a taxi rolling through a residential neighborhood at 25 miles an hour, except they’re going 150 or whatever, and they’re looking at you and talking. But they’re also looking there too. It’s I, you know, I don’t know.

They have talents and senses and calibrated ass. That just like normal people don’t have, I call that a speedometer. I like that. I’m gonna order one of those, but it’s just true. I, anytime I’ve ever ridden with a world class racer like that, it just reminds me how slow I am.

Don Weberg: You talked about racing, you talked about meeting Mario Andretti and all those people.

What about meeting auto industry executives? Have you guys spent much time with those [00:25:00] people? Matt, I know you have. I know you got some great stories. Good, bad, indifferent.

Matt Stone: I would say most times good. And I met a lot of them, and I particularly enjoyed the designers. The automotive designers or now the independent ones who designed great cars and went on their own, founded their own company.

I knew Tom Char very, very well. I think Gito Gito, he’s the goat, Giro is the goat of all ever and ever. I mean, just go through his roster of cars and you’ll just go, this came outta one head from one guy’s pencil. What’s with, how did that happen? I really enjoyed hanging and banging with the designers, especially at an auto show.

I used to go walking around with Tom or others and we’d walk up to whatever concept car and they would talk and I would listen and occasionally they’d ask my opinion. I thought, well that was really nice, but they don’t care ’cause I wanna know their opinion. So the designers were terrific. I’ll give you one example of, of two guys coincidentally that worked for [00:26:00] the same company for a while.

They would be Robert. Lutz. Oh, Bob Lutz and Chairman Lido, a AA Coka.

Crew Chief Eric: Mm.

Matt Stone: Those guys as car company executives, they could smell it in the air. They had this nose, whether it was a trend or impending doom or whatever, they could just smelled the car business in the air, and they just had instinct. Now, did they make mistakes?

Of course they did, but they also each achieved great things and saved companies. Those guys were fascinating just to sit and talk with Lotts, and he goes on and on about what’s right and wrong with the car business or this car company. He smelled it in the air or the water, or in the blood or whatever.

And Mr. Iaccoca too, I mean, you know, not every Iaccoca car was great. A whole lot of ’em were successful either as machines or as sales. Most of them were pretty smart guys and gals, some, not all the racing drivers ’cause [00:27:00] of our need for speed and all that. That’s one thing and, and because of course how great they can all drive.

But I enjoyed the designers. The senior most car executives that I could get FaceTime with, Luca Cordero de Montelo, he chairman of Ferrari for a number of years, positively brilliant guy, and has so much heat and so much enthusiasm for the car business. You, you can’t believe it. And he would be the first one to tell you that when he took over all the things that were wrong with Ferrari and then he proceeded to go like a target shooter and fix them one at a time.

Those guys are fascinating. Yeah, of course there’s, there’s guys that tanked and went nowhere and were supposed to be the great saviors of whatever company and did nothing. There were those two, but generally some pretty interesting. And smartphone,

Preston Lerner: I will say. I mean, the ones that I met, they were all impressive and it’s, you know, outsiders can always criticize and say, oh, what a stupid idea.

The solstice or whatever. The Aztec, we can all agree the Aztec, there you go, someone messed up. But I mean, by and large, the [00:28:00] people I met were all really bright. They were really committed. They were real, mostly car people. I mean, I didn’t meet that many who were just bean counters. I’m sure they were there, but it’s just that I think cars is a, it’s a tough business.

It became a lot tougher when you had a lot more foreign competition. Margins are small and it’s a hard way to make a living, and so no one gets a ride all the time. Cut people a lot more slack than some of the critics do.

Matt Stone: I will also say the smartest, perhaps, of all of them that I have ever met and spoken to Roger s Penske, I’ve heard that quite now.

That is one smart dude. He’s too smart to be president, but he’d make a great president. But you know, he runs a global business employing like 70,000 people and you know, race teams that have been there, won that, and again, car dealership groups. As a guy who owns a big car dealership group, he is so influential he can and has convinced various car makers to do or not do something.

Because his brain operates at a different level than mere mortals. [00:29:00] I have nothing but immense respect and affection for Roger Penske as a truly brilliant and nice man who just

Crew Chief Eric: really gets the car business. Was there a story that got away, something still that you wanna write about, someone you wanted to interview?

Preston Lerner: I used to do a lot of stories about young guys before they had really succeeded or also some women, ’cause I also did Danica Patrick just sort of getting started out and I was gonna do something on, uh, Jeff Gordon and he had just moved up to Cup and they were going to do the first Brickyard 400, I believe it was 94.

And I pitched the story to automobile about follow Jeff Gordon. He’s going back to do, uh, indie, which he originally wanted to do Indie as Indy car guy, but you know, ended up being shunted over to to NASCAR because there was no future for Midget and Sprint car drivers in, in, in car. And so I saw this story to automobile and Gene Jennings Green lit the whole thing.

I set everything up and at the last second, David e gave the assignment to offend of his, to just do a general story on first Brick yard four. So I didn’t get to the story and Jeff Gordon won the race. And it was actually, it would’ve been like my greatest story ever. And Jean never forgot I didn’t get that story in.

She treated [00:30:00] me. Uh, she gave me assignments that I shouldn’t have gotten for years after that. Just to say I was sorry for not giving me that. That for me was the story that got away.

Matt Stone: I don’t know that I have any of those tales, that too much that got away. I didn’t, didn’t miss much.

Crew Chief Eric: But I bet you fall victim to the adage, never meet your heroes.

So was there one story that was disappointing that didn’t turn out the way you wanted it to, or it sort of broke the glass ceiling for you and you’re like completely disillusioned?

Matt Stone: No, not that I, I met my heroes and never regretted one of them. Everyone that I would’ve put in the hero category that I ultimately met.

I’m glad I did. And they were still my hero when we were done. And many became friends in that sense. No. Major mega disappointments. And I would love Preston’s opinion on this too. When you get in whatever car, and it’s supposed to be something that’s supposed to be pretty good and you want the cars to be good, but you’re disappointed when they’re not.

And that’s happened. I’m not avoiding naming a suspect, but I’m trying to think of a car I would name, but I remember cars that just, it was hyped and noise and you [00:31:00] wanted it to be good and it wasn’t. It just fell flat. And that’s disappointing. But you know, you, you have to write that story and you have to point those things out.

And I always did. Always and why. Yeah, that’s happened a few times. But anyway, press go ahead. How about you Again,

Preston Lerner: I didn’t do as much of the new car stuff somewhere better than those. I mean, I always felt thrilled to get in a Ferrari or get in those. Never disappointed for sure, but to get a little bit jaded.

’cause you got in all the really great cars. So when you were in kind of a standard family sedan, it was hard to work up too much enthusiasm. Back to

Matt Stone: Eric’s point a little, did you ever have that interview that you’re just waiting to kill it with somebody That’s really important, and you sat with that person an hour later and said.

I got nothing.

Preston Lerner: I did have a tape recorder fail on me once. Clearly some guys were better than others and, and Mario was the all time great. Mario was the best racing interview ever. Ever. Yeah. I mean he managed to convey his enthusiasm and he had great stories and I would, maybe not a lot, but certainly a substantial portion of racers were not race fans.

They didn’t succeed on the trek because they knew that N won the German Grand Prix and you know, beat the [00:32:00] Silverados, but they were just fast. Um, sometimes it was disappointing to talk to people who didn’t know the history or didn’t really have a perspective on what was going on. And, you know, some guys were better noters.

Mario was tremendous. The only guy who was really my hero growing up, Emerson Fitted Pol and meeting him after he went Indy for the first time was a thrill. He is the only guy who was autographed I ever got. He was great. Uh, a lot of fun. There were, a lot of them were great. The Hobbes, the Redmonds, they’re all great storytellers and, and it’s always fun to talk to him.

Some not quite so good, especially the younger drivers not as interested in the history of the sport.

Matt Stone: Yeah. The ones who have perspective and are mega talents. Those are pretty well, always good talks, always good stories, always good interview because they bring so much to the table. But you’re right, if they’re just too young and and haven’t really done big things, they have very little institutional memory, not necessarily crazy great successes to talk about yet.

Those can be a little disappointing. But generally, uh, the ones who have perspective and mega talent, they’re gonna give you a good interview.

Crew Chief Eric: I’m glad Matt, you brought up the cars ’cause that was next on my list. I wanna [00:33:00] share with you guys, just as an aside, and I know it’s gonna ruffle Don’s feathers, fellow journalist, I’m gonna put ’em in that category.

John Davis from Motor Week was on the show many seasons ago and I asked him a similar question, you know, ’cause he reviews cars all the time and he said his favorite car, he got to drive a Ferrari Enzo, much like Preston, right? He’s like, oh, Ferrari, that’s awesome. And so I turned the question around. I said, the car that you were hyped to test drive and to review for the show and was a complete letdown.

And he said the DeLorean. And he also added that he was really excited to buy one and because of the test drive, he didn’t. And he ended up buying a Panera instead, which he’s known for having a Panera for a very, very long time. So there you go.

Don Weberg: Well, on that note, Preston, if you’re not up to speed, I am a DeLorean junkie.

Oh, okay. Have more crap rattling around in his head about DeLorean than anybody has a right to know about. I love the cars. Yes, I know they’re not very quick, but when compared to everything else in 1981, they weren’t too bad. But I do remember going back to Road and [00:34:00] Track when the car came out. Calm Bryant, he wrote, I remember you opened the magazine and there was this double truck and the DeLorean didn’t slide.

I mean, it’s a really exciting looking picture. And I remember at some point in that article he writes that he really wanted to like the DeLorean. I mean, it literally just says, I really wanted to like the de DeLorean. I remember reading that. That always stuck with me and he kind of smooths it out over time.

He does say things about, maybe it’s not as quick as it looks, and maybe it doesn’t do things. We would hope it would, but the DNA is there. You can feel it. You know, this car can be more in its next iterations. I always appreciated that about him, that he didn’t quite slam the car. I’ve gone so far ’cause I have all these magazines from back in the day when the car is new.

And I remember the one particular journalist who will remain nameless for his own health, who wrote a really scathing review of DeLorean way back in 81. Fast forward to, I don’t know, 2000, somewhere [00:35:00] in there when DeLorean popularity was just starting to come around. Younger people were starting to get more interested in them.

And all of a sudden time was the great forgiver time, was making them a good car. And of course, back to the future had a ton to do with that. That same writer wrote an article about DeLorean saying what a great car they were, how wonderful they were, how ahead of their time they were. And I thought to myself in 1981, you tell everybody what a piece of junk this car is.

Now here we are 20 some odd years later and you’ve got the gall to come out and say, oh no, this car was ahead of its time and it’s terrific. So I found the original magazine where he bashed it. I found his little article and I put them together and I wrote a letter to him and I sent it to him and I asked him to please justify what he was trying to say.

Never heard back from him. And then fast forward a couple years later, LA Aldo show, press days, pop up and guess who I run into? And there he is. Yeah, I shook his hand. I said, hi, I am Don Weiberg, how are you? And [00:36:00] he is kind of looking at me like, I know that name. And I said, yeah, I love your review of the DeLorean.

Gave him that deadpan stare. The look. I’ve never seen a face go white so quickly. And I’m just like, oh my God, this is actually a lot of fun. Now mind you, what I was not prepared for? How old was I? 25, 26. Matt. He was like, your age. Okay. So I’m looking at him like, oh, he’s supposed to be my boss or something, and here I am basically telling him off because he doesn’t know anything about cars.

And that was the fact. Over time I’ve learned that that guy actually knew very little about how cars, it was who he knew in the publishing industry that he kept getting these jobs and for some reason he kept getting thrown into the automotive circle. It was really, really weird. For the record, I was not that

Preston Lerner: journalist.

I just want that on the record. I know

Don Weberg: I looked you up. I know of what you wrote about Zaka You Okay. In my book,

Preston Lerner: did that interview you for his book, by

Crew Chief Eric: the way?

Preston Lerner: Yes, he did.

Don Weberg: I go novan.

Crew Chief Eric: So I know I opened Pandora’s [00:37:00] box by bringing this up, but actually we stepped backwards into a really important final point about the day in the life of an automotive journalist, which is the risk you take about what you write and what you publish.

Can you keep track of everything you’ve written over, let’s say a career 20, 30 years? And just like Don’s anecdote, did that guy even remember what he said in 1981? Was he thinking that far, you know, 20 some years ago? So has that ever happened to either of you guys where you’ve had to, you know, recant what you’ve done or gone back or, you know, the letter to the editor was specifically pointed at something that you wrote, and how did you handle that?

Preston Lerner: There’s some things I’ve written that I wish I had written differently. The most embarrassing moment ever was an email I sent, which was not for publication, and it somehow got published. And then I heard from, uh, Leo Levine, the author of the Dustin, the Glory Great Ford Book, which I love. It was one of the great books ever.

And he then wrote a second, the Dustin Glory two, which, or that’s not what it was called, but it was, it picked up the story after 67 and it was not as great as the first book. And that’s what I’d said in my email. To an editor who shall remain nameless. And he published that. And I got a [00:38:00] call immediately from Leo.

What, what? What did you like about the book? And that was, that was bad. But I have to think back for a while to see if there’s anything I wanted to recant. Nothing comes immediately to mind, but I’m sure there was some, I’m sure there are many things I got wrong over the years.

Matt Stone: I can identify offhand something that I would absolutely recant because it was terribly wrong, factually incorrect.

Awful, awful, awful. We’re humans. We make mistakes. You have opinions that other people disagree with. That’s fair game. And there were times when I had to answer those letters, and some of ’em I did answer. I mean, if somebody came to me with a well reasoned objection. I’d be happy to engage them and I did.

If they’re just, you know, out there, pure bashers who know nothing bashing me, the magazine, the story, and your mother and your, you know, all of that, I don’t have time for that, for that ignorant explosion kind of thing. I could care less That person’s an idiot. Or at least acting like one. But if somebody will engage me professionally and courteously with a disagreement, sure, I’ll have that conversation anytime.

Preston Lerner: Sometimes there’s some group think is [00:39:00] inevitable, you get a lot of guys together and something comes up and sometimes some opinions become sort of standard issue, even though they probably shouldn’t. I remember Finity and Alexis came out in 89. A lot of the, the sports car guys liked the Infinity more.

The Q 45 was, you know, a much more dynamically interesting car than the LS 400. And so we thought, oh, this is gonna be the killer car. Well, of course seems like Q 45 ended up being a bit of a disaster and the LS 400 reshaped the entire luxury car industry. So yeah, I’m sure I was guilty there of getting that one wrong.

I’m sure there’s a bunch of stuff like that, but I don’t recall ever being confronted like by Don or anybody, anybody like that. So I better

Don Weberg: take note of

Preston Lerner: maybe after they see this episode I’ll be in more trouble.

Don Weberg: Yeah, it’s okay. Preston, I’m doing a little research now on your work and I’m gonna have to call you after this.

I’d like to have a few words.

Preston Lerner: I do wanna know who the journalist was though. Maybe after. We’ll do that when the red light’s off,

Don Weberg: right? For me, I wanted to be an auto journalist. That was what I wanted to do. I, you know, you guys are talking about the racing cars guys as your heroes, the Andrettis, and you know Matt Preston, you guys.

Or my hero, you were the ones that I would [00:40:00] pick up a road and track a MotorTrend car and driver and auto week, any of ’em, and read those stories about the new cars, about the classic cars, and to a young guy raised around cars, but looking to learn his own voice in the auto dom

Crew Chief Eric: Auto sphere.

Don Weberg: Auto sphere.

Very good. Yeah. You guys were the ones who gave me the knowledge to develop my voice. You were the ones who gave me the thought processes as to, gee Don, why is it you started liking Corvette a little better than nine 11? What happened there? Well. Reading about it and you guys putting it into words. So me, I took an internship, I wrote a letter to MotorTrend editor Steve Van Toon, who graciously called me, said, please come to my office.

I’d like to meet with you. Let’s have a conversation about what you’re doing and what you wanna do. The guy was fantastic, absolutely incredible. And that was where I met Matt. That’s where I met everybody else. But that was how you did it. In the old days. You wrote to somebody you wanted to be part of.

You saw them as the authority, you wanted to learn from them. So that’s where I went. Now that being said,

Crew Chief Eric: so we’re gonna [00:41:00] switch gears. Talk about books. We’ve interviewed plenty of authors on this show, and I always kind of ask them, Matt included the journey of 80,000 words. Where do you start blinking cursor on the screen?

It’s a lot different than writing an article or something like that. It’s more serialized to make things more complicated. When you’re writing your own book, it’s your voice, your opinion, your story, your fiction, whatever it is. And you’re working with an editor, but you two have co-authored some books.

How do you come to agreement? How do you write it in such a way that it’s seamless and how does that work with editors? Can you explain the process of co-authoring a book together?

Preston Lerner: The first book we did together, it was Matt’s project. It was a Paul Newman book. Matt had me come in towards the end to help out with some of the racing portion of it, specific ’cause Matt had done a great job with, uh, especially the attainment, the movie winning and the cars.

That was a great chapter on the, uh, the movie cars. And I was doing kind of more sort of the inter nuts and bolts kind of, uh, racing side. We each wrote our own material and then we vetted each other’s material. So it worked out really well. ’cause these days there [00:42:00] are no real editors in the book publishing world.

I mean, there, there’s copy editors. It’s not, you’re getting first edit people giving you good ideas about what to do. So we were fortunately able, we were both writers, we’ve both done some editing, so we’re able to look at each other’s work, I think, and make it better. I think the voices sound pretty. I mean, I, I don’t know, people could tell the difference between what we wrote or not.

I think it was pretty seamless. And so we handed in something that we were happy with, get my perspective on this as well. But I was happy with, anyway, what, what we handed in. So it didn’t really need to be edited and we actually probably didn’t really want it to be edited ’cause we were happy with the product that we submitted.

Crew Chief Eric: Does it get even more complicated though, when we bring self-publishing into the equation? Something like an Amazon where you really have to do your own work. Have you guys ventured down that path at all?

Preston Lerner: I’ve never done that, but I, I also write a. Fiction and first book I sold. The only novel I sold so far, unfortunately.

I mean, there was a New York editor who, he went through the copy page by page and he had thoughts on what needed to be done. You know, all the books I’ve done, I haven’t done as many as Matt, but done seven or eight now. And I mean, there’s really not much input from [00:43:00] the editors at the publishing houses. I mean, they give you, you know, you.

Talk about what you’re gonna do ahead of time and then you pretty much deliver the product and then it is copy edited and proofread.

Don Weberg: What about like fact checking? Is that part of the editing process? Does the publishing house go into that or do they pretty much just trust you to turn in a book that’s ready to go?

Uh, you know, Matt, you just recently wrote the DeLorean book, and how did that go? You turned it in, did they go through it and make sure all the facts are correct? Is there somebody at the publishing house that does that,

Matt Stone: in that particular instance, Don? Yes. The commissioning editor, the guy who I reported to, so to speak, at motor books on this project, he normally could have and would’ve done it himself, but he was very, very, very busy at the time with numerous projects.

He hired a woman to do a, a copy, edit and proof, and she just did marvelous research. She would come up, she said, well, I found this here, and you said this. Are you comfortable that you’re right, or is this guy perhaps right? Or is everybody right? And, and [00:44:00] her attitude and style to President’s Point made it better.

Mm-hmm. Now, you, you, you can get somebody who just, they’re stuck in Wikipedia. I mean, I use Wikipedia, but is it my only source for everything I ever write? No, of course not. That’d be foolish. Mm-hmm. I want that. I want it to be good. I want it to be right and accurate, and that process, as Preston said, makes you better and makes the work better if it’s good.

Crew Chief Eric: Right. If

Matt Stone: it’s somebody who’s just anxious to make a name for themselves and steal your project. That’s very dissatisfying. I think only one time have I ever had that, and it was a project that Preston and I also worked on together. Oh right. That was, you remember who that was? I do, isn’t it? I don’t think is there anymore, is it?

I don’t think so. I think that person who shall remain quite nameless isn’t there. But yeah, when it’s bad, it’s awful. ’cause then you start questioning yourself,

Don Weberg: right?

Matt Stone: And then you got a negotiation with this person of authority. Well, he’s the editor he’s supposed to know. Wait a minute, I did the homework.

I know, and [00:45:00] you get feeling like that sometimes, but if it’s a good collaborative thing, you’re all on the same page, you understand kind of what the book’s gonna be, and you do your homework, it’s fine.

Don Weberg: How do you justify your answers? In other words, in that, in that scenario where that lady walked up to you and said, well, I have this guy here saying A, you said E.

Do you have notes on the situation? How do you say to that person? Well, this is how I came to my conclusion.

Matt Stone: When I’m doing a book project, I have banker’s boxes next to my desk, and I keep every stitch of anything that has to do with that book, whether that’s a screen print, an interview, a magazine article, a book, whatever.

I build my own personal internet by the pound, and it depends on the quality of the source. And in some cases it’s the source period. It’s a direct quote from so-and-so who invented the thing. And I have his SAE paper or his interview right here in front of me. Miss copy editor, or who are you quoting? I keep everything handy until it’s done.

And again, [00:46:00] sometimes there’s a little bit of a negotiation and if you can’t agree, there’s nothing wrong with saying historical sources or authorities do not agree on this issue. Here’s the two viewpoints, and I’ve done that and it sounds like a cop out, but it’s like, wait a minute, I wasn’t sitting there.

Lightning doesn’t strike with the answer. So if their source is credible and honest and was well founded and mine is a good solid direct source, I’ll say, well, here’s two opinions. Here’s from the guy that designed it and here’s from the engineer that built it.

Preston Lerner: Nothing wrong with that. I mean, I love fact checkers.

I wish they had more of ’em. Maybe it’s some publishing houses. They devote more to that. I do know that automobile, I mean they had a part of the copy editing process was fact checking and they were really vigilant. You know, sometimes it was frustrating. You don’t wanna have everything questioned. But I think it was good.

I mean, it was rarely a time where Randy Blackwell was there. He went to Car driver. I think he still had car driver, but I mean, rarely he didn’t catch something or at least something that we had to discuss. And I think that’s, that’s really important. You know, to Matt’s point, sometimes the sources don’t agree and sometimes you’ll find sources disagree with the historical, what was [00:47:00] written back in the day.

And you have to sort of make a judgment call about, you know, what’s right or what’s wrong. But, you know, it’s the famous New Yorker article about fact checkers, where one of the stories is, it was about the invention of the, uh, vibrator. The guy who invented it said it was ’cause his wife was frigid and the wife said it was ’cause he was impotent.

And the poor fact checker had to like talk to the two people on asked which, which was it. And I guess they sort of didn’t get that one resolved. But I mean, fact checkers have a tough job. So I, I like to, uh. Help them out as much as I could.

Matt Stone: At the end of the day though, it’s my opinion that great editing makes you better.

If it’s really great work. Somebody who’s not out to be a hero and put their voice into what you wrote, you know, if somebody’s editing without ego and and is just really good on facts and style and the root tenets of journalism and all that kind of stuff, great. Editing makes my work better. I want that.

Don Weberg: Have you guys, either one of you individually or together as a team,

Matt Stone: have

Don Weberg: you ever worked on more than one

book

Matt Stone: at a time? I have. I have done it. It can be tough. You have to be really [00:48:00] smart and hopefully kg and good about, I don’t want to be working on two projects that have the same deadline or on the same schedule.

If I’m finishing up this and I’m just starting to wanna chase something new, that’s okay. I’ll start gathering information, might do some interviews, maybe do a little writing, but I want book A to be well down the river and on its way to the press. Before I get too far into book B, but I had a collision one time and it was hell.

I’ll be honest, it was very difficult for me to make that separation in my head comfortably. I did it, got away with it. It was fine, but it was tough.

Preston Lerner: Yeah, I’ve never done, I mean, I would always do freelance work while I was writing, so sometimes you had to because you had to make a living, you juggle. Yeah.

There’s not a lot of money in car books, especially racing books. I mean, they’re not laborers of love. Exactly. But magazine work just pays so much better that that’s what would pay the bills, and so I had to make sure I was left time to do those assignments and did the books as time permitted, or you know, after dinner or something.

It’s nice to be able to stretch out on a project, you know, instead of doing, you know, a feature story of [00:49:00] 2,003,000 words or 5,000 words is a really long feature story. By modern standards and book you get to write 50, 70, a hundred thousand words. It’s fun to be able to stretch out like that. It’s great to have that opportunity because you can’t do that in a magazine story.

You just just don’t have the space.

Crew Chief Eric: You know, you guys have written so much. You’ve spent your whole careers writing. Are there any stories that you feel. Are underrated or overlooked in automotive history that maybe deserve more attention, a little bit more light shined on them.

Preston Lerner: What’s really good, you mentioned Amazon and self-publishing, which once upon a time had a really terrible reputation.

Vanity Publishing was what it was called and and people look down upon it and what’s happened is, is now because the economics have changed and the software has changed, there’s now the ability to write books on subjects that never would’ve been published because you couldn’t make money writing a book about Lloyd Ruby.

I mean, that would’ve been really borderline. Well, now you can do that. I mean, you can, you know, you can do that with desktop publishing. Makes it possible. So I think a lot of subjects that were too obscure to get through the mainstream media and really get out there in the world because they didn’t pencil out financially, I think now are plausible when you go to auto [00:50:00] books.

This is the bookstore here in Burbank, pretty well known all over the world. I mean, there were just hundreds of books that I would happily buy if I could afford to buy all of ’em about subjects that, you know, they would’ve been an article, a 2000 word article, and now it’s this 80,000 word book on Eddie Sachs.

That would not have been done, you know, a generation ago, or even a decade ago, because no publisher would take that on. How could you possibly make it work? So I, I do think that’s a great thing that’s available now, and I’m, I’m happy to see that.

Matt Stone: Tell you one, Eric, that I would love to see researched and written by a relentless team of Wall Street Journal level investigative reporters.

And I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but there’s too much meat on this bones. I’d really love to know, did the big three put Preston Tucker down? Ooh, that would be good. I wanna know for sure. I have a feeling that there’s a lot that people know that hasn’t been said, although a whole lot of ’em are probably dead by now too.

I don’t know. Was Preston Tucker promoter and maybe a, a bit of a huckster and a this, that and the other thing? Yeah, maybe. But boy did he come up with one [00:51:00] outrageously fabulous car. It was right at, you know, the end of the World War and car companies were scrambling for dollars, and I do know that within the halls of certain car makers, they saw that car and went, holy crap.

That I do know. I’ve read interviews to that effect, but nobody has ever said for sure that some faction of the big three put him down or absolutely did not. There’s several books out on Tucker and everybody talks some about it and did the SEC, the securities exchange violations. We’ve got all that, but did somebody just make sure that he didn’t make it?

I’d love to know.

Don Weberg: Okay. Let’s dive right into it. Journalism, how has it changed since you began your careers? Where do you see it going? Join me. I’m Phil Donahue. What do we see from where you’ve been to where you are to where it’s going?

Matt Stone: If I were the smartest guy, I would know that, but I’m not, so I don’t.

Preston, please back me or jack me on this. The whole internet and connectivity [00:52:00] and anti-social media and all that kind of stuff changed it immeasurably and irreparably in a whole lot of ways. That’s where I think the biggest paradigm changes came. Where is it gonna go? I wish I knew that. But there are countries, England particularly, that still seem to be able to turn out these beautiful long form magazines with long form stories and lavish photography and fabulous magazines, and sell ’em for 10 or 12 bucks, which nobody here in America seems to be able to do.

So where’s it gonna go? I don’t know, but that to me was the paradigm shift, the mysterious interwebs. I

Preston Lerner: started getting journalism and I got a journalism degree, got a job. My first job with Don, you’ll appreciate this, was out in Abilene, Texas, about three hours west of Dallas. And at the time that they had not just one, but two daily newspapers, they had an afternoon edition.

In the morning edition. I’d say about half the people who worked there were people like me, the young guys and girls who wanted to go on to bigger jobs, and we wanted to get to the big city. And the other half were gonna stay in Abilene. And they raised a family on it, being a newspaper reporter editor or [00:53:00] working in the back shop.

There was a back shop back then because you actually had to physically put a paper together. You didn’t just do it all on the, on the computer. And, um, you kind of thought that that was gonna be something you do for the rest of your life and you retire. And that was it. And in our lifetime, that just completely disappeared.

I mean, Craigslist destroyed the classified, you know, the internet changed the reading habits. I mean, I’m not saying anything new. We were obviously, but, and clearly that came on to effect the card journalism. Moral as well. I mean, again, when Matt and I started four or five of these, it was more than that.

But I mean, there was a bunch of Alist and Blist magazines that were great magazines that looked like that was something you would do for the rest of your life. You know, they’ve like all disappeared. It’s, it’s a really sad thing. And I don’t know if I would go into drizzling now if I was starting out because it’s, it’s a different field.

I don’t know how you sell yourself. I think Substack is an interesting future, and I do think that’s a way you can make a living. But I think you’re more of a commentator, you’re more of a pundit and you are a reporter. And for people who wanted to be straightforward journalist, I don’t know where you really do that anymore because.

Even we’re out here in la. I mean the LA Times is a shadow of what it used to be, and it’s like the third biggest paper in the country. It’s a very, very sad to watch car journalism, especially because of the internet. And now you have [00:54:00] so many influencers and you know, people doing car reviews so-called where they’re getting a car from, not more manufacturer even, which, I mean, there was always, you know, some sort of questions about, you know, how objective you would be.

I, I think we were objective, but there’s always been, you know, people question it, but if you’re getting a call from manufacturer. People now get ’em just from a car dealer, you know, and you’re doing the review right there. And how honest can you be under those circumstances? Completely different field. And I wish that it were doing better and I wish I could be a little more optimistic, but I’m not that sanguine about the future.

Matt Stone: I’m a little bit in the same boat with Preston. I mean, telling somebody how to learn and train and make a living as an automotive writer, I’m not sure that’s an answerable question from where I sit. It would be a, a short speech or a long boring one. I’m not sure which. One instance I just heard from a public relations person for one of the car companies was telling me that they had an event and they, and they had, I guess some of these folks were on liners and some of ’em were influencers and this and that.

They paired up driver and a ride along to go drive this vehicle wherever, like 30 miles. And I mean, we used to do road [00:55:00] tests a lot longer than 30 miles. Can I get an initial impression in 30 miles? Yeah, probably. But what she told me is this one particular outlet person. Did not have a driver’s license.

So the person he or she was teamed up with in the car drove the car. So this writer, editor, influencer person took the pictures with a phone and all seemed to care about was the technology in the car. If I paired it with my phone, what could I make it do? How good was the audio system, the nav system? All the infotainment and was it smooth?

It didn’t break down. Yeah, it drove, it went good. That’s all he cared about. ’cause that’s from the right seat without knowing how to drive, that’s all he could talk about. So that was a little bit of a, A brain shaker to me,

Don Weberg: definitely shows a different direction. That’s actually really amazing. Let me, let me throw this one out there because one thing I’ve observed over the years, you know, I came as kind of a hybrid when I started interning with Matt.

Yeah. The internet was just starting to get a little bit of traction, just starting to kind of get [00:56:00] going. I was classically trained in all the print journalism, so I was going after that genre. One thing I see now compared to back then, thanks to technology or technology be damned, however you wanna look at it, it’s so much easier for anyone to be an automotive journalist or an influencer, however you want to say it.

The question is the quality. Can you trust this person? What does this person bring to the game? Why are you listening to this person when you’re wanting to know more about the Mazda Miata or the Ferrari 3 0 8 or whatever, and here’s this one person you always go to or these two people you always go to.

You almost have to figure out who’s more trustworthy. I guess where I’m going with this is I wonder if your younger chances are you grew up with this stuff. You know how to run the camera on the phone, you know how to edit. Do you guys think, as you know, as having been there, done that, seeing the future where you were as to where it came, do you think that’d be a good place for a young person to start?

Is just to dive in the pool? If you think you’ve got what it takes to be an automotive journalist, do you make those little [00:57:00] videos? Do you make those commentaries? What advice would you give to somebody who wants to do this? What do you think? I don’t,

Matt Stone: I don’t know Don. ’cause I didn’t come up that way, so I’m not sure exactly.

I think one of the other things which Preston touched on a little earlier is, you know, back not too too many years ago, you know, working at a magazine or a newspaper was the way to make a living. Yeah. Posting to your blog may or may not be Joe Bob’s cool car site without an income stream. You can mechanically do all that, but is it from your grandma’s basement?

Do you make a living? Are you professional at that? I think that’s a bit of the missing link in the equation of your question and, and what does the person wanna accomplish if they wanna make a living? I think it’s a hell of a challenge now. Or do they not need to make a living? I don’t know. This is Blackwater for me and I, I don’t know that I have a credible opinion.

I’m not saying no, or that I don’t know. I’m not saying no, but I’m saying I don’t

Preston Lerner: know, sort of listen to myself speaking. I kind of feel like I’m sort of a parody of the Boomer complaining about everything, and I don’t wanna sound that way. I, it just meant it’s, it’s tough. But I do think, and I actually did have lunch with [00:58:00] somebody, a young guy who was trying to get started and he was making his own videos.

But I still think it’s important somehow to have some sort of journeyman status where you, you’re either an intern or you’re, you start at the bottom or you start at a smaller place where you kind of learn the ropes. It’s sort of hard to get into the business. Fully formed. You know, again, I was, there were small magazines that I started working at where, you know, the pay wasn’t very good and writing for them, and kind of that’s how I learned to do things.

And I was sort of mentored by other people, and I hope that people can still do that. I’m sure that there’s still ways to do that. I guess I like mad. I’m a little bit don’t really know the social media world, and so I don’t really watch any YouTube videos. I don’t know exactly how that works, but I do think somehow you wanna be able to find somebody to help you along so that you’re not on your own.

So you have somebody sort of giving you some tips and helping you make progress if you can do it without somebody’s help or more power to you. It’s just, it seems like a pretty tough road to hoe I, if I were starting out, I would try to find some other people who are doing what I want to be doing and somehow approach them and see if you could get them to help you or something like that.

Matt Stone: A mentor who understands all sides of the coin, you know, I don’t [00:59:00] understand developing these income streams for somebody that needs to do this, earn a living. Is that part of the equation? Probably is. But how does all that get developed? I couldn’t tell somebody. To Preston’s point, if they’re gonna be somebody who’s gonna be tutored, mentored, big brothered, whatever, they really ought to have some grasp of all sides of all facets of the rock.

Because without that, okay, you can operate your video camera and you can say, oh, this is a cool car goes fast. But how does that provide you a living? You’re both talking about

Don Weberg: the new generation, the old generation, how they work together. Here, I’m gonna hit the bull that I’m staring at and I don’t know if you guys see it or not.

Artificial intelligence. You said go find a mentor, go find somebody you look up to. Okay, well I had a trillion of ’em in the autom. Is artificial intelligence, the new mentor, is that where young people can go and type in a question? Dear Mr. Chet, GTP, I want to be an automotive journalist. How do I do it?

Matt Stone: That’s a good question. For certain types of [01:00:00] information, AI can be extremely helpful. As a clearing center is the rounding up stuff. I would say going back a little more to what you said earlier, find and listen to voices that speak to you, and if there’s a way to communicate, Hey, I like your stuff, you know?

Mm-hmm. How do I do what you do? Well, you tell me. Will you share that to me? Not knowing Sounds like it could even be viable. I bet if you ask. GTP how to do that. The answer ain’t gonna make a lot of sense. It might say, oh, you need to go to journalism school and then go to this. And I don’t know,

Don Weberg: I’m looking at Eric’s picture thinking, Eric, can you do this right now?

Real quick, five

Crew Chief Eric: seconds. Yeah. Don brings up a very valid point, you know, coming from the tech world to hear the argument all the time about how artificial intelligence is gonna make all our lives better. It’s the foreshadowing of Skynet. And I wonder though, if writers will be replaced by bots, you know, bots being the chat gpt of the world and you know, all those kinds of things.

So Preston, what’s your thought on this kind of looking at it?

Preston Lerner: I’m really worried about AI and, and the future that I’ll have for writing. I mean, [01:01:00] I think AI can definitely take over a lot of the stuff like, remember you, you know, the new car guides were like a staple of the industry for years and years and years.

They were big money makers. You know, you’d write like 120 words on each model in the GMC lineup, whatever it was. Well, geez, AI can do that in a heartbeat. There’s no reason why it won’t be able to do that. You know, I kind of felt like I was sort of insulated because to do a profile of a race car driver, well, how’s it gonna do it?

You have to interview the guy. I mean, AI can’t do that. I mean, I guess there probably is a way I could do it, but I, I kind of felt a little bit insulated. And also I’m kind of aging out I think, at the right time. But yeah, I do think it’s gonna take a lot of the entry level stuff out. I mean, a lot of the press kit material, which used to be a big deal for the people on the PR side, you know, someone had to write those press kits.

Well, I think the AI can will be able to knock those out in a heartbeat.

Matt Stone: What’s missing from that part of the equation is the voice ua, the perpetual voice. If you ask Chad GTB, what’s it like racing a Camaro in the TransAm series? You ain’t gonna get a piece that sounds like Brock Yates, I promise you. To me, that’s [01:02:00] a great clearinghouse for facts and numbers and wheel bases and all that, but opinion, analysis and voice.

I don’t think we know that yet.

Crew Chief Eric: Preston brings up a really good point about aging out of the industry and Matt, you’ve moved on to being an author now and as you look back over your careers as automotive journalists, what would you say outside of meeting your heroes and driving fantastic cars was the most rewarding aspect about telling stories in the automotive world?

Preston Lerner: I mean, it’s been a great ride, not just since I got to do interesting things and meet interesting people, but because as you say, you gotta tell stories. You got to relate stories to, uh, readers, at least editors. I don’t know if the readers were reading the stories or not. It is still really rewarding to do that.

There are stories that, that are untold or that haven’t been told properly. The ability to sort of set things straight, explain what really happened. I still find that to be a very satisfying experience and I enjoy the ability to talk to guys and women who have sort of maybe gotten their do you know, to tell their story is also something that [01:03:00] I really appreciate the ability to be able to do.