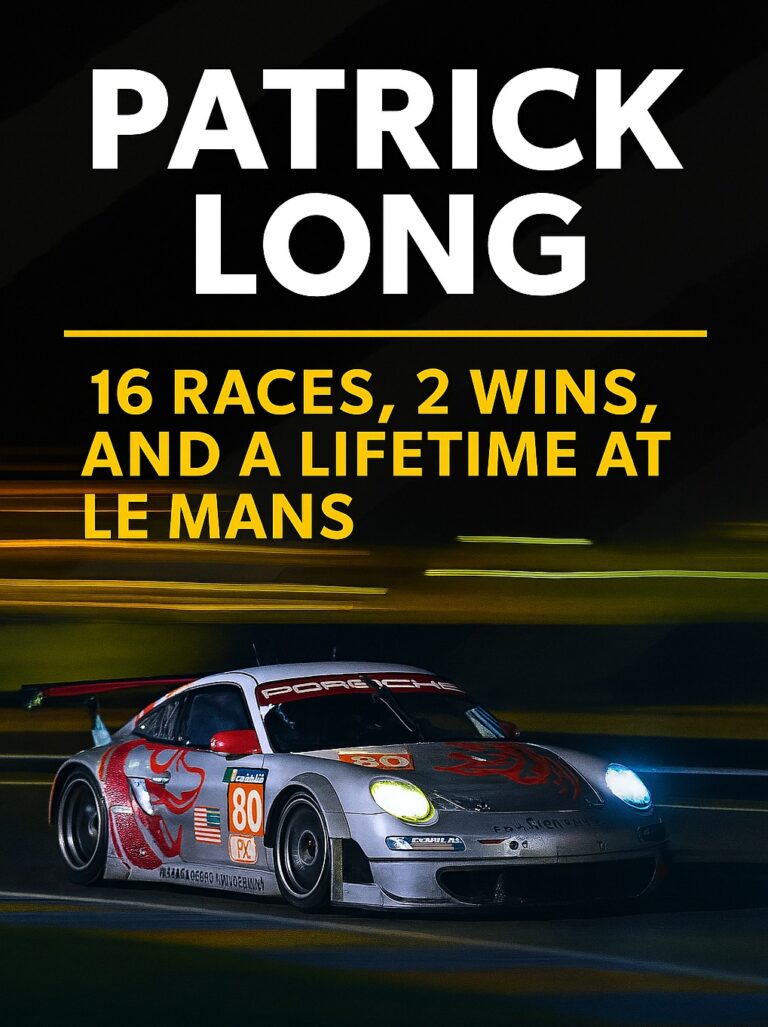

In the pantheon of American endurance racing, few names resonate like Patrick Long. As Porsche’s only American factory driver for many years, Long carved out a legacy at the 24 Hours of Le Mans that spans 16 consecutive starts, two class victories, and countless memories that blend grit, grace, and gratitude.

In this edition of “Evening With a Legend,” hosted by our very own Crew Chief Eric, Long reflects on his journey from a young karting hopeful in Southern California to a seasoned veteran on the podium at La Sarthe.

Tune in everywhere you stream, download or listen!

Long’s Le Mans story began long before his first race in 2004. In 1999, as a teenager, he was selected by Elf Fuels to attend La Filière, the French racing academy based at Le Mans. Living full-time in the Technoparc, he raced in the French Formula Campus series and soaked in the atmosphere of the 24-hour race as a fan. That year, he witnessed the infamous Mercedes flips – Mark Webber going airborne – and felt the visceral pull of endurance racing.

Fast forward to 2004. Long made his Le Mans debut in a Porsche GT entry alongside factory veterans Sascha Maassen and Jörg Bergmeister. With Roland Kussmaul engineering the car, the pressure was immense – but so was the payoff. They won their class. “It was surreal,” Long said. “I was the rookie, the liability. And yet, we ended up on the top step of the podium.”

That first win came in an era when endurance racing still demanded mechanical sympathy. “We had a throttle cable issue, maybe even a clutch issue. You’d get pushed into the garage, lose laps, and still come back to win. That was endurance racing at its core.”

Synopsis

Sixteen starts. Two wins. Countless stories. Patrick Long’s Le Mans career is a testament to endurance—not just in racing, but in spirit. “I was a Porsche fan long before I ever drove one,” he said. “And I still am.”

- What do you remember most vividly about your very first time racing at Le Mans, and how did it differ from what you expected?

- What is it about the Circuit de la Sarthe that makes it so special and demanding compared to other tracks you’ve raced on?

- How did it feel to achieve your first class victory at Le Mans (in 2004), and what do you think were the key factors that led to that success?

- Of your 16 attempts, which races/years stick out as the most memorable to you, and why?

- Can you describe the unique relationship between a driver and the Porsche brand during such a demanding event?

- Was there ever a thought/chance/plan to run in any of the Porsche prototype cars like the 919? Thoughts on the 963?

- Over the years you raced at Le Mans, how did the atmosphere, competition, or technology evolve in ways that stood out to you?

- Now that you’ve stepped back from full-time racing, how do you reflect on your Le Mans legacy, and what does that race still mean to you today?

- Do you see yourself participating in future LeMans Classic events? If so, is there a car you’d like to race, from any era of endurance racing?

Transcript

Crew Chief Brad: [00:00:00] Evening With a Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to legends of the famous 24 hours of Le Mans giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

Crew Chief Eric: Tonight we have an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you sharing in the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing. And as your host, I’m delighted to introduce Patrick Long, widely recognized as one of America’s most successful endurance racers with an impressive legacy at the 24 hours of Le Mans.

As Porsche’s only American factory driver for many years. Patrick competed in 15 attempts from 2004 [00:01:00] to 2019 at the helm of a Porsche GT class entry. He achieved class victories in 2004 and 2007, showcasing his skill, consistency, and deep understanding of endurance racing. Known for his smooth driving style and strategic mindset.

Patrick became a staple presence on the Cir d Losar, representing Porsche with distinction and helping solidify the brand’s dominance in GT racing. His Le Mans’s career reflects not only personal success, but also his vital role in strengthening the presence of American drivers on the world of endurance racing.

And with that, I’m your host crew chief Eric from the Motoring Podcast Network, welcoming everyone to this evening with a legend. So Patrick, welcome to the show.

Patrick Long: Thanks, Eric. It’s a pleasure to be here. And yeah, when I had that email and ACO comes up, that’s an acronym that’s very, very close to my heart and special in my life.

So it’s great to be here and to reminisce a little bit about such a special race and a special racetrack.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, we got a lot of ground to cover as racers. We like to talk stats a little bit here, so let me kind of [00:02:00] put things in context. We’ve had the privilege of interviewing all sorts of legends on this show.

So let’s go from the bottom to the top. Andretti and Jordan Taylor. Nine attempts at Le Mans Hurley Haywood, 13 attempts at Le Mans. You’re clenching the second spot right now with 15 attempts right behind David Hobbes with 20. That’s a lot of things to cover in a single episode. So how about we just focus on the big ones, and everybody likes to know about the first, right?

Because your first impressions or lasting impressions, so talk about. What you remember about your first time at Le Mans?

Patrick Long: Yeah, that’s a great sidebar for me to just quickly mention that. In 1999, I was a young Go Karter from Southern California and Elf Fuels had stood up as the supplier of our carting series that ran nationally and said we were gonna send a few Americans to La Fre, which was an academy from the French Federation of School, and be based and live at Le Mansr in the techno park and.

Compete in the French Championship [00:03:00] one Make Formula campus. What that all meant was that I was vying for a seat to live full-time in Le Mans and I actually did that in 1999 as a a young aspiring professional. So fast forward only four short years, and that was my first time showing up to compete at Le Mans.

And I never would’ve envisioned that I would get maybe three attempts at Le Mansll, let alone 15 in a row. An amazing, amazing memory. But yeah, the first year that I showed up, a daunting racetrack, a big learning curve, and big shoes to fill because the good and bad news was I was in one of the two lead Porsche entries, Roland Kuzma, the legend and icon of so many decades at Le Mans was my engineer and my teammates were Porsche’s veterans.

Factory driver, Sasha Mossett and Urick Berg Meister. So very, very overwhelming from beginning to end and it just made it that much more incredible that that year we ended up on the top step of the podium in the single GT category at that time.

Crew Chief Eric: We’ve heard different stories in the past. You know, people [00:04:00] talk about how they learned Le Mans.

First practice lap out. They’ve never seen the track before. Others have said it was their first European circuit that they ever raced on. Was that the same thing for you as well? Had you raced other places in Europe and when did you learn that first lap at Le Mans?

Patrick Long: My time in Europe started in 1996, racing carts in the summer, in the world championships, and then it became a full-time affair in 1998 with a year of carting, and then it moved to Le Mansr for 1999.

And from there I sort of traversed through Europe looking for opportunities to cut my teeth and race against the best from all over the world. And you know, in that era, I think British Formula Three was really the pinnacle of single seater categories and drivers looking to make it to Champ car, to Formula One two.

Le Mansr and I never had the funding to get. Quite two British F three. I remember testing just before I had a phone call from Red Bull to go through the Driver’s Academy for the inaugural Formula One driver search to get an American Formula One. And although that [00:05:00] story I’ve told many times didn’t end up as the ideal or the end goal for me, that is where I met.

Porsche and Parley a, an amazing career of 18 years with them. And today, you know, some four years after my full-time retirement from racing, I still work for Porsche as a brand ambassador and as a consultant in Motorsport. So no, very much not my first time racing in Europe, not my first time at Le Mansr, and not my first time attending the race.

I had been to the race three times prior as sort of a fan and just loved the experience of it. My first year was 1999 when I was living there. Know that was a wild race, and specifically with the Mercedes episodes and Peter Rech and Mark Weber going upside down as so many remember and probably attended.

Scary stuff, put it all into perspective. But the way I really sized up my first 24 hour experience, that being the 1999 Le Mans was. I spent 12 or 14 hours at the racetrack, went home, had a barbecue, had a full night of rest, woke up, had breakfast, [00:06:00] came back, and those same crazy drivers were still going around the racetrack.

And it really put it into perspective just how grueling it is for man and machine and what a fast and dangerous racetrack that was. So safe to say I was hooked. Just have loved it every single time I’ve been back since.

Crew Chief Eric: So you’ve mentioned throughout this, you know, the special qualities of Le Mans, how big it is, how daunting it is, the grueling nature of the race itself.

How do you compare that to some of the races in the United States or other ones? ’cause it isn’t the longest track compared to, let’s say the Berg Ring 24 or some of the others that are out there. So when you compare and contrast some of the other places you’ve been, is Le Mans still the most special? Is it, or is it the keystone in all the tracks on your list?

Patrick Long: I think it is the most special as a racetrack and how it flows, how quick it is, but also just how much rhythm there is and how much different challenges and layouts of corners there are. And it’s evolved in the time that I’ve been there. Certainly changed in some ways, but you know, the Porsche curves remain some of the most.[00:07:00]

Fast blind and challenging set of corners in all of Motorsport. I think I would liken the Porsche curves to a street track only. You’re going about three times the speed that you would be going at Long Beach or Detroit or Monaco. So just a wild, wild place. To answer your question a little more specifically, I would say in 2004, when I first drove some laps there in the pretest, it was the most daunting.

It was the fastest it, it did seem like the highest risk track I had ever competed at or driven around, but certainly nerve gring and Bathurst for that challenged to me and my driving and my nerve as much as Le Mans. I think Le Mans became a second home to me. I felt like a specialist there because I was. So fortunate to get to compete so many years in succession that I just was always first one out of the plane and on the way to the track because I couldn’t wait to get out there for qualifying.

I couldn’t wait to start the race and battle in that first hour stint because the whole world’s eyes [00:08:00] were on the television or there live watching that race. So just an amazing energy that I didn’t feel at any other sports car race I ever competed in.

Crew Chief Eric: And it’s funny you say that because a lot of folks try to compare.

Let’s say the Daytona 24 to Le Mans, and it’s like apples and chainsaws, right? You can’t really make that comparison. But I will say there’s other wonderful tracks in the United States with natural elevation like Laguna Seka, Watkins Glen, and you pick it, you name it. But after my first visit to Le Mans, I suddenly understood why Petite Le Mans exists at Rhode Atlanta because it is sort of a miniature version of Le Mans.

So do you get that same perspective having raced on all these tracks, even across the United States?

Patrick Long: Yeah, I would say so. The elevation of a lot of domestic racetracks is pretty unique. I mean, you get a lot more elevation at road Atlanta than you do at Le Mans, at least from a driver’s perspective. Maybe not from a topography or engineering side, but I would be willing to venture out and say that, you know, going to most port or anywhere in North America Road America, they have a lot [00:09:00] more elevation and Le Mans feels flatter as a driver.

You know, the Moozon straightaway is so much scale and such high speeds coming from Arage all the way back to Indianapolis feels dauntingly narrow, especially when you’re trying to coexist with three different classes and three wide moments. So Le Manss still challenges you to be so precise and to never let your guard down because the average speed is just.

So high and the stakes are so high, but the prestige, and again, I’ll keep referencing it, the energy of the fanfare and everything that comes along with the race in its spectacle is still untouchable, in my opinion.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s go back to your first Le Mans 2004, and you said yourself, you’d already been there a couple years, so now you’re resident of Le Mans, or you know that’s your second home.

What was it like at the end of that race? Getting up on the podium after all that time and all the work and the effort and working with Porsche? You look down at the crowd and you go, I’m on the podium at Le Mans, did you feel like you had just landed on the moon or what was [00:10:00] that like for you?

Patrick Long: It was surreal.

I certainly didn’t expect it. I really couldn’t believe that we had won our class in a pretty. Tough fight with another Porsche and it went down to the wire. But I remember, well that this was a cusp of GT racing where when we qualified, we were still running a synchro H pattern gearbox. And you know, this car still had three pedals and was very bare and inside very few driver aids and much different than where I ended up at the end of my career competing at Le Mansll.

So you really did have to take care of the car and you did have to battle back. From adversity and spend time in the garage and come back from many laps down as someone else hit some troubles and had a mechanical issue or an off on the track. And those are my fondest memories. That was endurance racing at the core, and I felt like I caught the tail end of that traditional man and machine, where later down the road.

Everything, the tires, the brakes, the gearboxes, the [00:11:00] engines, the competition, everything was so robust that it absolutely was just pure qualifying laps from beginning to end. You hit every curb in sight. Every single shift was a red line. So I really love and respect and remember fondly that. Age old endurance race where you still had to take care of the car, take care of your competitors and your teammates, and we had a throttle cable issue, if I remember correctly, and maybe even a clutch issue, and seeing the team go to work being pushed backwards into the garage and getting out of the car actually, well, you know, under green flag conditions and still being able to win it lent itself to huge emotion because you, you had a little bit of surprise that you actually still won the race with everything that you saw and went through in that 24 hours prior.

Crew Chief Eric: I wanna dovetail off of something you said there. You mentioned that you were at the tail end of that analog generation of cars, repeals, H pattern, all that. So when you stood up on the podium and you look back at all the drivers and legends that came before you, was there somebody who had [00:12:00] inspired you, somebody you thought of as you’re standing there, you’re like, I’m standing in the same place that so and so.

Who drove a nine 11 or drove a Ferrari or something like that. Who was your inspiration?

Patrick Long: Yeah, there were so many people that helped me and inspired me who had competed at Le Mansll. Danny Sullivan was a huge, huge help in my career. He’s still such a close friend and a mentor, and obviously he had great success at the racetrack with Porsche.

I also thought about Andre Pesca. You know, he would’ve been there that day, but Andre was really the. Mentor of the Elf La Phillie Air program that I had gone through, and Anri was just a no frills guy. He said what was on his mind, he wasn’t a man of many words, but he treated everybody equally and with respect and gave good, solid, direct advice.

And he of course, had so much presence at that race, not only as a driver, but as a team owner. And so a long list. But those two guys were definitely on my mind standing up there, as was my own father who, you know, really was [00:13:00] a, a humble natured carpenter and surfer from Southern California that put so much on the line to give me the opportunities to even get a chance at racing professionally one day.

So it was, uh, an emotional day.

Crew Chief Eric: I’m sure a lot of folks wanna hear more specifics about the nine 11, which we’ll get into. But before we do that, I wanna ask you sort of one more question about your time at Le Mans, and this is where it gets difficult, right? We got 15 attempts at Le Mans, which years and races stuck out to you.

I mean, I could pick some and throw darts and we could talk about specific years, but there’s gotta be some memories, maybe memories or mishaps. That really stick out to you in those 15 attempts that made one year or one season stick out more than the other?

Patrick Long: Yeah. I mean, obviously the successful years where the end result was P one are amazing.

I’ll briefly touch on oh four. I was the rookie, I was the liability and I had mentors as team teammates and team members. A few short years later, 2007, I was the elder statesman in the car, the one with the most experience, the one that had to qualify and start the car and lead the team with [00:14:00] set up and direction.

You know, only in a few years, the Le Mans felt like very much like a home for me, and I felt a different sense of emotion when we won that race and driving for IMSA performance. Matt moot a French team from Ruen just up the road with a big insurance company from France on the side of the car. It was a, a much different feeling than winning with Peterson White Lightning in 2004 with a, an All American crew.

So it was kind of the bookends and a great, great memory. Many years with flying lizard there. We never had a victory, but we had great fights, great times, and yeah, gave it our all. And then I guess I’ll finish off with a high point of three years with Patrick Dempsey and everything he brought to that race and brought to the energy of Laal and just.

A lifelong friend. We didn’t win in 2015, but we finished second and we fought our way up onto that podium, and that was Patrick’s lifelong dream was to stand on the podium. So that second was as emotional and as happy as any victory, and a lot of it was secondary to seeing someone else [00:15:00] realized their dream and all that that came, and all the emotion that he was having and the pressure that he had faced in the years and.

Days and hours of time that we spent preparing for that to get him to a point where not only could he hold his own out there, but put in the hours to get up onto the podium. I have a couple of memories of tough, tough moments at Le Mansll, and scary moments as well. You know, danger is always present in Motorsport and certainly at Le Mansll.

In 2011, my junior teammate from Porsche, Mike Rockefeller, had a massive crash on the back straightaway in a Audi, I think it was an r. 10 or 12. And, uh, I came through that incident and I didn’t know who had been in the car, but I just remember driving slowly through carbon fiber. There was really nothing left of that car.

And luckily Mike was over the barrier, a little dazed and confused, but had crawled out of that wreck. And that was a scary moment. And there were a few more that were maybe more tragic and more memorable for the wrong reasons. But without going in too much detail, Le Mansr [00:16:00] taught you to respect it. It taught you that every time you were out on track, you had to be at the top of your game and that the danger was always clearly and presently there.

Crew Chief Eric: There’s so many different ways we could take this whole different threads here. So let me ask. Some audience favorites. First, let’s just jump right off of where you stopped and you were kind of leading towards oops moments, and for a lot of drivers, those oops moments aren’t the ones you see on television.

They’re not on camera. They happen behind the scenes. In the pit box. Is there a. Funny sort of oops moment for you and all your time at Le Mans.

Patrick Long: Quite a few. I remember maybe the second attempt I was back with Peterson White Lightning driving with Yrg Burmeister and Team Oard, two Porsche Legends and great friends.

And I remember Yrg was. Ill. And so my second time at Le Mans, Timo and I, back to back stints all the way through pushing hard on a very hot race with an overheating car. So the cockpit temperatures were high, and I just remember being so fatigued at the end of that. And luckily I was in my twenties, so I had [00:17:00] plenty of reserve energy, but just being so sore and my bottom side being so sore that I couldn’t sit on a chair, I was just ruined.

But laughing about it and getting through it another time, Patrick Dempsey was. He was drawing fans. I mean, we couldn’t go anywhere in that town without a frenzy of at least a couple hundred people trying to run each other over to get a glimpse of him. I mean, his show, Grey’s Anatomy was bigger in Europe than it was in the us and I didn’t know any of this and I had never really traveled with a big celebrity or star like that.

But I had fought my way in 2013, my first time driving with him. We had fought our way up and we were in a pretty solid lead in our class, and I remember the German engineer coming over the radio. Could have been Jim Jordan, actually from the US who was translating for the team. But one way or another, the team said to me, look, you’re gonna pit this lap.

There is a amazing amount of journalists and fanfare around the pit box. It’s live on Eurosport and it’s. Twilight and everybody’s here, so just be careful as [00:18:00] you come in the pit box. Well, I pull into the pit box and I couldn’t see the crew. I couldn’t see Patrick. I just saw flashbulbs and the entire pit box was covered with traffic.

And so I got out of the car and I made eye contact with one of my young mechanics, and he looked over at me and shook his head like, I can’t get to the car to even change the tires. It was pure instinct, but I just started ripping journalists and photographers and anybody who had access to the pit lane.

One by one, just pulling on their lapels, their necks, anything that I could get ahold of to rip them out of the way. And I remember there was a wide shot of the pit lane of me sort of clearing human traffic so that we could get a team onto the car and maintain our lead in the class. So just all kinds of wild times like that.

I mean, coming back, being stranded out in the middle of Moozon in the middle of the night, and the crew not even knowing where I was. And of course, having to retire. Hitchhike back to the town that we were actually pitted in. So yeah, that’s one way I kind of put into perspective racing at Le Mans is you [00:19:00] travel through three or four different villages in a lap, so you get different weather patterns and all different types of things.

So yeah, it’s, it’s always an adventure and always have enjoyed it.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, you’ve done some name dropping throughout this. And a lot of the fans like to hear about who was your favorite teammate. So you mentioned Dempsey, you mentioned Borg, Meister, and Timo. Who is the best to drive with?

Patrick Long: Oh man, that would be a tough one to pick.

Just one, and this is gonna sound political, but what I learned is even your greatest enemies and arch rivals sometimes ended up as your teammates and when you were as competitive as pro racing drivers seemed to be and were in my time. Instantaneously. You are one and you are a unit and you really do pull all in the same direction.

And you know the week later when you go back to ALMS and you’re competing against each other in rival cars, you might not talk anymore. But I didn’t have a teammate that I didn’t enjoy at Le Mansr. I think you spend so much time together, not only in the lead. [00:20:00] But the schedule is something that I always tell people who go to Le Mans for the first time is really study how the schedule works and where you have to be in your prime and pace yourself because you can wear yourself out all the way through the week with late qualifying in practice and then Friday not being in the race car and all of the different things, the drivers parades and things.

But I might have done as many Le Mansr with Yrg. I don’t remember all the stats. They certainly drove with him more years. In my career than anybody else, probably eight out of 10 years, a certain period of time. Yorg Berg Meister was just a wild man and, and somebody that on paper, him and I were about as opposite as they come, but we had such a bond, such a trust and such a mutual respect.

And then of course, Patrick Dempsey is a big name and he is a recognizable face and, and he is all those things. But beyond all that. He’s such a historian of the sport. He’s such a racer at heart. He has so much love and so much optimism that it reminded me not to be cynical, not to take things [00:21:00] for granted, not to let the result disallow you from looking around and realizing what a special opportunity we had to even.

Be at Le Mansr, let alone competing or ending up on the podium. And it sounds cliche, but you know when you’re that hyper-focused, sometimes you don’t see the forest through the trees. It’s just the next session, the next problem, the next lap time, the next need. And sometimes Patrick reminded me and just would put his arm around me and just say like, this is so incredible and this is such a gift.

And you sometimes need somebody like that, especially when you can be as intense and goal-driven as I was in my prime.

Crew Chief Eric: Intense and goal driven, I think is the middle name of the Porsche team. Right? I mean, that’s what they’re all about. We’ve heard that from other people in the past. They’re very to the point, very exacting.

So let’s talk a little bit more about that unique relationship with a team with a factory and an engineering group like Porsche. Obviously, your whole career is built around that. Even your career after your career is very Porsche focused. Tell us about being one of the [00:22:00] few American factory drivers at Porsche.

What was that like?

Patrick Long: It’s a huge responsibility. It’s of course, the coolest car company in the world, in my humble opinion. And as long as they were willing to have me on the team, I was gonna stick around because I believed in the product. I believed in the culture. I loved the history of the company and the way that these cars looked and felt and drove.

I think there was a complete aura around Porsche and everything they’ve done at Le Mans, and you really have that sense of the crest that you carry and what that means and what you’re expected to do. And as an engineering company, as a design company, and as a racing company, have always been present in Motorsport, but specifically at Le Mans, if you think back to their first class victory with the 3 56 sl, I believe in 51, it’s a long run for them.

And. Every single car that has that Porsche badge on the hood has a a large part of their history. And that was always sobering for [00:23:00] me as a driver, but it also inspired me and it bred confidence because they’re loyal, they’re prepared, they’re intense, and they’re reliable and quick. And that was the ultimate dream for a young kid to be driving for not only, um, a car company.

And a group of individuals who stand for those things, but an entire brand worldwide in what it stands for.

Crew Chief Eric: Given your illustrious racing career and the opportunity to drive all sorts of other cars along the way, was there ever a car that you walked away from and said, that’s as good as a nine 11?

Patrick Long: You know, I think that it would be unfair for me to say that.

I didn’t enjoy or look at other cars or drive other cars that I didn’t have tremendous respect for. I love the grunt of a V eight. I love cheering on all different brands in what they do, both in racing and outside of racing. But there is this allegiance in this attraction that I had, not just because Porsche ended up where I made my living, [00:24:00] but I was a Porsche fan long before I ever drove one.

And the. Connection of the driver and the car, I think starts at a young childhood in how it smells and how it feels, what sounds it makes, and the squat of a nine 11, the small cockpit and the sound of a flat six. Those are all things that I have boyhood memories of. And then from the racing standpoint, I always believed that I could red line shift and break as late as possible and rub fenders and doors.

I just believed in the product that it was not. Fragile. I respected it, but I also believed that the Porsche way in the engineering and the Porsche intelligent performance meant that I had a rock solid tool to do my job. And what else could I ask for? You know, I was a pretty aggressive driver and I would curb that in the 24 hour races.

At all costs, but there were times where you didn’t have that choice. And I loved that aspect of just how hard I could push the Porsche product, whether it was a LMP two car with a V [00:25:00] eight in it, or a flat 6, 9, 11. There’s great, great times with all the different types of product, you know, driving all the different generations of not only nine elevens, but of mid-engine prototypes and all the different types of race cars that Porsche engineered and designed.

Some of the coolest parts of the job and still is, is that you get to sample things that were from decades long before my career. There’s this common thread through each one of the cards, whether it’s the ergonomics of how they fit and feel, or when you crank the engine, and that part of it is just super special.

Crew Chief Eric: Your 15 attempts at Le Mans Cross. Over the evolution of the nine 11 during the period of the 9 96 through the 9 92. So out of all of those, is there one you prefer over the other? Is it the first one, the 9, 9 6 with the manual transmission? Or is it one of the other nine 11 variants?

Patrick Long: I had a pretty big soft spot for the 9, 9, 7, especially the narrow bodied cars in the nine elevens.

I would say sort of. 2000 7, 8, 9. I [00:26:00] loved those cars because they were still relatively analog and you know, it wasn’t full paddle shift, it wasn’t mid-engine, it wasn’t too much tech. But at the same time, they made proper downforce and they had the speed, you know, once we started pushing well below four minutes with some small modifications to the racetrack, but it just felt like an arms race.

I remember being south of the four minute mark and then it seemed like every year we were going three or four seconds a lap faster. So it really did progress there through the middle part of my career. And those were the fun days because every single year we went there, it was development of new parts and wherever the homologation might have been and the cars didn’t stay the same very long.

Crew Chief Eric: Let’s talk about perceived rivalries. You mentioned, you know, rival drivers. That you competed with an A LMS and things like that. For those of us that are fans watching Le Mans three plus thousand miles away or more, if you’re in California, you watch it on tv, there’s always this perception, Porsche versus Ferrari, Porsche versus Corvette.

For you driving at Le Mans, was that a [00:27:00] real thing or was it different than that? Or was there an actual rivalry between Porsche and Ferrari and Porsche and Corvette? And if there was, which one do you think was the harder one to really beat at the end of the day or keep off your tail to make sure you locked in the podium?

Patrick Long: Yeah, my memories of the Porsche Corvette rivalry were much more stateside for one reason or another. I don’t remember having too many hard locked in battles with Corvette, and that might’ve been because of the different class overlap and the timing of what car and class I was in versus where they were entered.

But certainly Ferrari, especially in the early first half of my career at Le Mansll, that’s who we were gunning for. And I remember that REI being a US-based team, would put one of the best efforts out there. They were tough. There were so many battles between Porsche and Ferrari and specifically Re and we knew if they had a perfect race, they were gonna be tough to beat.

And, and they knew that about us at Porsche and it was always respectful. It was tough. There was little gestures [00:28:00] and elbows up jokes that were made and had, but we always understood they were just straightforward and were there for the same reasons as us. So very fond memories with. Rick and Giuseppe and all the drivers that they had that came through there.

That red car was, was a tough one.

Crew Chief Eric: So let’s talk about the prototypes for a moment. Was there ever a chance to drive the nine 19 or were you just happy with the production cars? What was your plan within Porsche? Or did they have you sort of boxed in?

Patrick Long: My opportunities with prototypes came pretty early 2006, sort of couple years into my factory driver stand.

I started with Daytona prototypes in the Grand Am at that time, and then not long after that with Roger Penske and RS Spider Program stateside in in the American Le Mansll series and in imsa. In 2008, that was my one full season in LMP two, but that year I was called up to drive a GT car at Le Mansll, although there were a couple of [00:29:00] customer efforts with the RS Spider and very successful ones at that.

So never raced a prototype at the 24 hour Le Mansll, but grateful for those opportunities in the prototype categories racing for overall wins. And for people like Roger Penske, I mean, that still goes down as a huge highlight for me, not only to have that name on your overalls, but to have Roger himself calling every one of my races in 2008.

You know, there was an intense respect between us and we spoke openly at all times, but it was clear Roger was there to win and it all focuses. So, um, yeah, still running to Roger and like I mentioned in the pre-show. Beginning to drive his latest 9 63 RSP this past weekend. It, it’s been, uh, a longstanding relationship with those guys and just a huge amount of respect for them.

Crew Chief Eric: What do you think of the 9 63?

Patrick Long: It’s wild. I mean, the, we touched on it. I’m kind of old school at heart. I like an ignition button and a break bias. Yeah, you strap into the modern LMP [00:30:00] cars and it is an intense amount of different protocols, levers, lights. I mean, just to put in perspective, the steering wheel had three paddles on each side, so I had six different paddles.

There was probably 20 buttons on the steering wheel and another 20 buttons off to my right. And this isn’t a pretty small cockpit. And there were a lot of different cadences to the combustion engine and the hybrid engine communicating. The simplest one. In my first time when I drove the race car back in 2023, I had some lapse at Laguna Seca during Rensport was how do I even get this thing outta the pits?

And of course you get the 130 page log on how to operate it, but in the end, you really just ask your fellow drivers and they give you the quick direct route to it. So you start. In electric power mode as you leave the box and then at a certain point you get a display on your dash that says bump start ready, and that’s when you release the proverbial clutch and then the combustion engine fires up and that’s when the fun starts.

So it’s, yeah, just incredible to touch all different types of tech. But in this day [00:31:00] and age, the 9 63 is is a very complicated car.

Crew Chief Eric: So knowing what you know now and looking at the last couple of years of Le Mans, the GT classes are pretty well sorted. The balance of performance is there, you know, there’s some really great competition, there’s some really great racing at that level.

But up at the top, it’s getting interesting. More and more brands are getting involved. You’re hearing things about Hyundai and Ford’s coming back, and I mean, just everybody’s coming out the woodwork to run an LMP. In your opinion, what’s missing from the 9 63? What’s holding it back now that you’ve driven one, you’ve been around them, you know about them.

What’s the magic thing that they gotta do to make that car win at Le Mans?

Patrick Long: If I knew, they probably would want to hear it from me, but I, I. I think that clearly 2025, they gave it a heck of a run and to finish second, and to have as clean of a race as they did with a great, solid strategy was inspiring. But Ferrari’s been tough.

They have had it covered and it’s. Playing your cards correctly, you have gotta build a car. That’s great for the entire [00:32:00] WEC and IMSA season. And Porsche’s proven to be ultra strong on the full season and I think that’s a big focus is winning the championship outright. Naturally, everybody wants Le Mans as well, and I’m sure they’re working hard on that.

I don’t have that answer. When I go back to my own career and my own experience, the hardest part about setting up a car for Le Mansll is that you have to be quick in the straight lines. There’s so much straightaway at Le Mansll, but you can easily get focused on that one lap pace. And then forget that you’ve gotta last an hour in a stint and that you need your tire underneath you and you need to be quick through the Porsche curbs and you need to be good in breaking and all the things that downforce bring to you.

But of course, that’s a balance of drag. So it’s making efficient downforce, uh, where you’re slippery and quick in a straight line, but still have that tire underneath you and, and the driver’s confidence to go really quick through the Porsche curve. So, yeah, all speculation from my side, but I’ll just come and say it.

I’ve [00:33:00] had perfect, perfect races at Le Mans. We have never slipped up or lost a second in the pits or had anything go wrong and finish outside the top five. And that’s because there’s balance of performance. There’s adversity in weather and other things outside of your control. So even having a perfect race and having three drivers that are all identical in their perfect pace doesn’t guarantee you anything at Amal.

At least not anymore and and that’s why it’s so great to watch.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, I’m glad you went there and you mentioned strategy and how important that is to racing. I wanna know more from the perspective, not of the team strategy, but of what you as a driver have a role in shaping the decisions from the cockpit.

And I bring that up because you hear about this more and more when you watch Formula One, you get Max and Charles going, leave me alone, just let me drive. Right? They got the engineer parroting something in their ear all the time, which is distracting. Does that relationship exist at the 24 in the same way?

And if so, how did you influence the engineers and the pit box to say, Hey guys, this is what I think we need to do.

Patrick Long: Yeah, it [00:34:00] comes back to a few things that are really like that home court advantage knowledge of how the racetrack evolves. Because what happens naturally is that you go to the pretest, which used to be a couple weeks before the race, and the track is pretty green ’cause of course the majority of it is public road used and there’s sand and you know, there there’s a lack of grip.

And then, uh, you sort of find a baseline set up and then you come back a couple weeks later, which of course is less time now as the schedule is a lot tighter, but. Still that evolution of the racetrack and really understanding how much grip is going to come in the racetrack over 24 hours of those roads being closed and the race being run.

So you have to be focused on qualifying, but not really other than bragging rights. I think qualifying has a little to do with the end of the race results. Maybe catching a safety car or something where you really do need to be starting up front. But in our days, I don’t think that. Qualifying really meant anything.

And therefore you really have to think long [00:35:00] term about how that car’s gonna drive. You know, at the end of the race, after two or three stints on a tire, we didn’t always have the ability to change to a new set of tires every single stint. And then again, taking care of yourself and as a driver, making sure that you’re not just chasing that one fast lap in practice or qualifying.

But that you can sustain 12 of 24 hours behind the the wheel. I mean, that was, uh, as big of a factor as anything was the ability to have that focus and that physical endurance to put those many laps in. And, and nowhere did I ever put as many laps in a 24 hour period as at Le Mansll. And when I say as many laps.

As many minutes in a race car. And so yeah, it’s, it’s a little bit of everything, but I’ll touch on it again. I think that’s why I’m so fond of the era of when I got to drive at Le Mansr, because it still had that endurance aspect to it, where today it’s outright full on sprinting.

Crew Chief Eric: So when we look at your start in 1999 at la.

Carting and living there and all that all the [00:36:00] way through 2019. So a 20 year run. You saw a lot of change at LA Mob. Now, when we compare that to Legends that came before you, they talk a lot about the old days where the Molson didn’t have the bus stops, and you know, this was this way and the pit boxes were certain way.

The big changes sort of happened in the nineties. And so you come on the scene, but you have a 20 year window. So what are the things that stuck out to you the most, whether it was atmosphere, competition, or technology that evolved at Le Mans in your 20 year run?

Patrick Long: I think the town, of course, grew, uh, in, in different ways and, you know, public transportation in different ways to bring more fans.

The racetrack itself operated and felt a lot differently, especially the pits. In the beginning, it felt like you very much had a pit lane and the overhead suites, but through the years there just was an abundance of development and new buildings and new fan areas, and so yeah, it felt bigger from beginning to end.

It felt much more electrified with [00:37:00] technology, and I think that in the end, the racetrack did. Evolve with different curbs and safety aspects, but only for the positive. I, I don’t think that there was anything that really was big enough change that the racetrack drove differently in those 20 years. And so that was the part I was always most focused on and and most grateful that we were able to preserve that.

Obviously the chicanes and Moozon came long before I did, but the track that I knew really only changed for the better with runoff and safety, but the layout and the driving. Emotion of the track always was retained.

Crew Chief Eric: All right, Patrick, we’re gonna switch to some crowd questions. We oftentimes have folks write in or send us questions ahead of time that they would love for our legend to answer on air.

This one I have to preface a little bit because she is one of your. Former pupils. So take you back to team USA at mid Ohio, and apparently you said something to Miss Sabra Cook at the time that stuck with her. And so her, first of two questions [00:38:00] for you is, did you retire from racing to focus on your social media?

Patrick Long: No, definitely not. But yeah, Sabra is a, a tremendous driver and, uh. Wow, what a, an ambassador for the sport and for her sponsors and her objectives. I, I always think that if I knew social media like her and some of the drivers that I mentor, I might be in a lot better place with endorsements and things of that nature, but.

Driving and calling it quits on a full-time career was a difficult decision for me. But at the same time, I’ve never looked back. I just was so fond of all the opportunities I had, and in this day and age, ironically, I look after many social media accounts, mainly for my company, lul and Air Water, two different experiential shows that we do.

Around the world telling stories of race and street, both vintage and modern, and all centered around Porsche.

Crew Chief Eric: So to add to that, she said, do you still believe, to quote you from Mid-Ohio, if I see you posting on social media during the day, that means you’re not training [00:39:00] or focusing on racing. Is that still true after all these years?

Are they now hand in hand racing and social media?

Patrick Long: I think so, and to answer that question, no. I feel like in this day and age, drivers are almost expected to cover their day, whether it’s business trading or driving on track. It’s an interesting debate because as we see drivers. Evolve generation to generation.

There’s certainly so much more out there. There’s so many more cameras, there’s so many more opinions. There’s so much more that you have put out there, but also that people have a platform to speak about. And I think it does in some ways change the driver comradery and, and the way that drivers are. And, and you look back and even when I started as a factory driver, there wasn’t any social media.

Different these days. And, and I think it’s, it’s not easy, but I do think it gives the fans a new way in, and everybody is kind of the director and star of their own little mini TV documentary of course, that everybody holds in their handheld phone. So [00:40:00] that’s the good news. You get to dictate, uh, how and what you share.

But I must have had some choice words for Sabre and some of the young drivers when they were coming through Team USA in regards to social media behaviors. I can’t recall.

Crew Chief Eric: That’s a good answer. And for those listening at home, they might not know this. You had a cameo in Brad Pitt’s most recent Formula one movie, and she wanted to know, are you taller than Brad Pitt?

Patrick Long: I don’t think I ever stood back to back with Brad, but uh, yeah, we’re probably very similar in our seat position because I shared the race car with him quite a few times in different scenes and also in preparation for the F1 film and what a guy, I mean for the amount of stardom that he has. Just so humble, so.

Easygoing but real. I mean, he wanted to know about the race car, about the racetrack, about how it all took place. And we shot a lot of that first opening scene for those of you who’ve seen the movie during the Rolex 24, right in the middle of the night, stint of 2024. And I took him next door ’cause we had a [00:41:00] pit box set up for us on Pittling during the race.

Just for shooting, but next door was our parody car in the right motor sports entered car. And so we sat up on the pit box and put a headset on him and he just couldn’t believe how intense it was and how much banter there was between the engineers and the drivers. And it was a super fun moment. And it just showed how passionate he was to learn.

And it wasn’t just about shooting a film, but that he really took his downtime to enjoy endurance sports car racing.

Crew Chief Eric: Do you think he’s gonna do something like Dempsey did and go racing himself?

Patrick Long: I don’t know. I think he’s had great amounts of seat time shooting, both in the formula cars and the sports cars, and you know, he sampled the McLaren Formula one car after the movie released, but no intel from my side.

I think that he’ll probably drive some race cars and certainly show up at race tracks. But as far as going at it in any, any way, shape or form like Patrick did, I wouldn’t bet on it. But you never know.

Crew Chief Eric: The gentleman driver is still a thing at Le Mans. It’s one of the few places where you can still do that.

So maybe we’ll see Brad Pitt at [00:42:00] Le Mans one of these days for real, behind the wheel of a maybe a Porsche, right?

Patrick Long: Yeah. The first day we went out, we had a GT three RS Street car, a cup car, and a GT three R, which of course is the main car that races at Le Mans for Porsche. And we spent about an hour in the street car, we skipped the cup car and we went straight to the race car.

I just believe in immersing somebody in the environment that they need to get up to speed. And he had a, a real good feel and he was very trusting and listened. Yeah, all those laps at Daytona, I was honored to be guiding him around the racetrack, not just from the pit lane and, and on the radio, but in another car in front of him during those scenes.

And the scenes came out amazing and there’s been just great reception and so many messages that people really enjoyed the racing scenes, especially at Daytona. So very proud of that.

Crew Chief Eric: Scott writes, what was more stressful preparing for Le Mans or preparing for your annual Luka cult events?

Patrick Long: Well, I used to think that being a racing driver was a huge amount of prep and a huge amount of responsibility.

But once I started promoting my own [00:43:00] events and running my own business and having a, a team and logistics and budgets and protocols and safety briefings, I realized how fortunate I was and, and how fortunate so many pro racing drivers are because. You show up last, you leave first. Everything’s set up and built.

You have representatives who stand next to you and tell you where you have to be schedule wise and book your flights for you. And so, yeah, I had to learn the entire backside of movie magic or putting on a race team or an race event. And Luol is a, is a static display of cars. But what it is and what it represents, that a parallel to racing is, is that you have the preparation, the buildup, the logistics, you have the performance.

You have that time and day where everybody’s gonna be there, whether you’re ready or not. You don’t push deadlines, there’s no extensions, and then you have that celebration or defeat. You know, you have that aftermath and that feeling with your team. Going out and then starting all over and preparing for your next show.

And so I think [00:44:00] in many ways it’s been an amazing gift for me to have a, a focus beyond just driving race cars fast. And, uh, I try to add as many different elements that I learned in racing to Luka cold and to air water and to these Porsche events. And. I think we’ve sort of opened up a new segue to entering or allowing a portal for the younger generation to get into racing and into cars, and that’s always the goal, is to do something that makes an impact.

So super fun and it’s certainly never boring. So, uh, I wake up and I’m as charged up as I ever was as a driver.

Crew Chief Eric: Troy writes, how much do you think BOP pre-select a winner? Do you think BOP is a good thing? And why?

Patrick Long: I don’t think BOP selects a winner. I think BOP stems from taking manufacturers streetcars.

And trying to take a heavy, high horsepower car and a light low horsepower car and make them battle closely on the racetrack. As far as ground up prototypes, the goal is that everybody [00:45:00] has a shot, and what you really want is the ability for teams to fight it out with strengths and weaknesses on the track.

With driver strategy and things of that nature. But you know, I’m past the point of being employed as a racing driver, so I’ll probably be willing to speak a little bit more on this than someone who’s in it in the center of it. I think that there’s a little bit of gamesmanship depending on what the ultimate focus is, and a lot of things, you know, you have to decide when to play your cards and when to.

You know, not player cards, but with torque sensors and with the evolution of technology, there really isn’t the ability to sandbag. There really isn’t the ability to hide performance. And, and that’s why you have such hard races with so many cars, so close from different manufacturers. But I think what we all want is a fair fight.

I think that as a fan, you wanna see the ones who work the hardest, uh, who develop the best product. To have an edge. It doesn’t always have to be fair straight across the board. So [00:46:00] I think the officials have a very, very tricky and difficult challenge to monitor all of that, and it’s a very thankless job.

You only hear from the people who aren’t happy with the outcome of a race. You never hear from. The people that respect and admire just how much effort’s put in. So it’s a subject. They will long be debated, but if you look at where current prototype racing is, there’s more manufacturer support. There’s more depth of field in GT and prototype racing than I’ve ever seen.

So you certainly can’t argue that the formula is working.

Crew Chief Eric: All right, Patrick, one more crowd question before we go into our wrap up segment. Christopher asks, do you enjoy visiting a track and watching a race or does it still feel a little bit too much like a day at work?

Patrick Long: You know, personally, when I go to a track, I enjoy just like I did as a kid watching a good hard fight, but all the days leading up to the race.

If I have a focus, I love being there. I love the environment. I love seeing colleagues. I love the [00:47:00] energy, but just to be hanging out on vacation or as a fan now, I’d probably be at home. But the example being we spent three and a half weeks at Daytona shooting F1 the movie during and before and after the 24 hours.

And, and I loved that because I was working in. To the teams, different focuses, different goals, but being in that atmosphere and in that environment with a destination and with a focus, it was the best of both worlds. So still lots of love for the racetrack.

Crew Chief Eric: Now that you’ve stepped back from full-time racing, how do you reflect on your Le Mans’s legacy?

What does the race still mean to you today? And when you think back over that, do a little retrospective analysis, what did Le Mans teach you?

Patrick Long: I would say that Le Mans humbles you. It is such a prestigious event, and it is such a big name in the world of sport, but when you’re out on the racetrack going 200 miles an hour in the middle of the night, you’re all alone.

And at that point it can [00:48:00] be eerie. It’s you against the racetrack, and that’s where you have to have that humility in that respect for what’s going on with other competitors, danger. Focus on human performance and on performing and getting the most out of yourself. So I think it teaches you to be calculated, and because you’re going so fast, you really do have to be precise.

All of it was a rhythm and a flow. So I would just say humility, precision, and uh, respect.

Crew Chief Eric: You do a lot of historic racing now. I’ve seen you at the Monterey Historics. You’ve done red sport, a lot of other events now that Le Mans Classic is in full swing, starting with this year, they’re gonna do one every year alongside of the 24.

Do you see yourself participating at Le Mans Classic, and if so, is there a car that you’d like to run there? Particular era of endurance racing.

Patrick Long: I have not attended the race before nor competed. I do have a goal of being there. I don’t know what the race car would be if I was to choose one right now.

Maybe a a [00:49:00] 9 9 3 era, GT two Evo or an RSR only because. I think that that was the generation just before me. It was also the generation of nine 11 that was racing when I first attended the track in 99. Just one of my favorite street cars. So that’s one. The group C cars and GTP Cars of nine 60 twos 9 56 is, is just.

One of my favorite race cars to drive. So that would be another one high on the list. You know, 9 62 of last generations and twin turbos and more evolved brakes is, is a car that was just many decades ahead of itself, at least from a driving perspective. And so, yeah, one day maybe we’ll get the chance.

Crew Chief Eric: Lastly, what’s next, Patrick?

Patrick Long: Well, I’m sitting, uh, in, in our planning office and team office, and there’s whiteboards all around me and everything is about our upcoming show in Durham, North Carolina. We do an annual air cooled gathering. This year is our 11th. Edition and, uh, first time on the proper east side of the country.

So [00:50:00] time has flown. I obviously started this brand and, and this gathering and celebration reunion, it’s not just for car owners, but 85% of the people who come are not Porsche owners. And that’s, uh, one of the big parts of my focus these days. I also have a seven and a 10-year-old, so they’re at home excited and eager for me to come back and hang out with them.

And it’s just a super fun age, just a different cadence of life than it was when I was. 200 days a year on the road, but Porsche and Motorsport is all around me in my everyday life still, and for that I’m grateful and just continuing to get to ride this wave of taking my passion since I was three years old and 41 years later, still getting to play with cars.

Crew Chief Eric: Well, we’ve reached that part of the episode where I’d like to turn the microphone over to an a CO representative, and so David Lowe, president of A-C-O-U-S-A, is gonna have some parting

David Lowe: thoughts. Patrick, on behalf of the Automobile Club, Dilla West and our A-C-O-U-S-A community, I’d really like to thank you for sharing your story with us tonight.

It’s an honor to celebrate your journey together. [00:51:00] Thank you very much.

Patrick Long: Thanks, David. It’s been a great time. Thank you.

Crew Chief Eric: That wraps up tonight’s evening with the legend. We took a fascinating journey through the legendary Le Mans experiences of Patrick Long from his first time racing on the hallowed grounds of Circuit D Losar to his class victories with Porsche.

Patrick’s story is one of talent, precision, and unwavering dedication to the art of endurance racing. His impact on the sport, especially as the only American Porsche factory driver of his era has left a lasting legacy, both in the paddock and in the history books to keep up with Patrick and his continued work in motorsports, including his involvement with Luka Cult and other Porsche centric projects.

Be sure to follow him on Instagram and Twitter at pl motorsport, and you can also visit his official website@www.patricklong.com for more updates, appearances and insights into his career and current ventures. And with that, we hope you enjoyed this presentation and look forward to more evening with a legend throughout the season.

And Patrick, on behalf of everyone here and those listening at home, thank you for sharing your stories with us.

Patrick Long: I [00:52:00] appreciate it. It’s been, uh, a great time, very fond memories, and I’ll be looking forward to listening to your next episodes.

Crew Chief Eric: This episode has been brought to you by the Automobile Club of the West and the A-C-O-U-S-A from the awe-inspiring speed demons that have graced the track to the courageous drivers who have pushed the limits of endurance. The 24 hours of the Le Mans is an automotive spectacle like no other. For over a century the 24 hours Le Mans has urged manufacturers to innovate for the benefit of future motorists, and it’s a celebration of the relentless pursuit of speed and excellence in the world of motorsports.

To learn more about or to become a member of the ACO USA, look no further than www.Le Mansn.org, click on English in the upper right corner and then click on the a CO members tab for club offers. Once you’ve become a member, you can follow all the action on the Facebook group, [00:53:00] A-C-O-U-S-A Members Club, and become part of the Legend with Future Evening with the legend meetups.

This episode has been brought to you by Grand Touring Motorsports as part of our Motoring Podcast network. For more episodes like this, tune in each week for more exciting and educational content from organizations like The Exotic Car Marketplace, the Motoring Historian, break Fix, and many others. If you’d like to support Grand Touring Motorsport and the Motoring Podcast Network, sign up for one of our many sponsorship tiers at www.patreon.com/gt Motorsports.

Please note that the content, opinions and materials presented and expressed in this episode are those of its creator, and this episode has been published with their consent. If you have any inquiries about this program, please contact the creators of this episode via email or social media as mentioned in the [00:54:00] episode.

Highlights

Skip ahead if you must… Here’s the highlights from this episode you might be most interested in and their corresponding time stamps.

- 00:00 Meet Patrick Long: America’s Endurance Racing Star

- 01:42 Patrick Long’s Early Racing Years

- 04:15 Racing in Europe and Early Challenges

- 06:17 The Unique Challenges of Le Mans

- 11:53 Teammates and Inspirations

- 21:33 The Porsche Legacy and Racing Career

- 26:40 Porsche vs Ferrari: A Respectful Rivalry

- 28:16 Prototypes and Other Opportunities

- 29:48 Driving the 963: A Modern Challenge

- 31:03 The Evolution of Le Mans

- 33:29 Driver’s Role in Strategy

- 35:53 Reflecting on a 20-Year Career

- 37:35 Crowd Q&A: Social Media and Racing, The F1 Movie, and more!

- 47:30 Le Mans Legacy and Lessons

- 48:27 Historic Racing and Future Plans

- 50:40 Conclusion and Acknowledgements

Bonus Content

All of our BEHIND THE SCENES (BTS) Break/Fix episodes are raw and unedited, and expressly shared with the permission and consent of our guests.There's more to this story!

Be sure to check out the behind the scenes for this episode, filled with extras, bloopers, and other great moments not found in the final version. Become a Break/Fix VIP today by joining our Patreon.

Learn More

Evening With A Legend

We hope you enjoyed this presentation and look forward to more Evening With A Legend throughout this season. Sign up for the next EWAL TODAY!

Evening With A Legend is a series of presentations exclusive to Legends of the famous 24 Hours of Le Mans giving us an opportunity to bring a piece of Le Mans to you. By sharing stories and highlights of the big event, you get a chance to become part of the Legend of Le Mans with guests from different eras of over 100 years of racing.

What makes Le Mans so special? For Long, it’s the rhythm, the speed, and the sheer variety of corners. “The Porsche Curves are like a street circuit – but three times faster,” he said. “It’s a wild, wild place.”

While tracks like Bathurst and the Nürburgring challenged his nerve, Le Mans became a second home. “I was always the first one off the plane and on the way to the track. I couldn’t wait to get out there.”

Long’s second Le Mans win came in 2007 with IMSA Performance Matmut, a French team based in Rouen. This time, he was the veteran, leading setup and strategy. “It was a different feeling – winning with an all-American crew in ’04, then with a French team and sponsor in ’07. Both were special in their own way.”

Dempsey, Danger, and the Drive to Inspire

Among his most emotional races was 2015, when he co-drove with Patrick Dempsey to a second-place finish. “That was Patrick’s dream – to stand on the podium at Le Mans. Seeing him realize that was as emotional as any win.”

But Le Mans also taught hard lessons. In 2011, Long came upon the wreckage of Mike Rockenfeller’s Audi – shredded carbon fiber strewn across the track. “It taught you to respect the place. The danger was always present.”

Not all memories were dramatic. Some were just plain absurd. Like the time Long had to physically clear photographers from the pit box so the crew could service the car. “I just started ripping journalists out of the way. There’s a wide shot of me clearing human traffic so we could maintain our lead.”

Or the time he and Timo Bernhard had to double-stint through the night because Bergmeister was ill. “I was so sore I couldn’t sit in a chair afterward.”

Teammates, Rivals, and the Porsche Brotherhood

Long shared the track with legends – Bergmeister, Bernhard, Dempsey – and counted them all as brothers in arms. “Even your greatest rivals became teammates. At Le Mans, you pulled in the same direction.” He had a special bond with Bergmeister, his most frequent co-driver, and deep admiration for Dempsey’s passion. “Patrick reminded me not to be cynical. To look around and realize what a gift it was just to be there.”

Driving for Porsche wasn’t just a job – it was a calling. “They’re loyal, prepared, intense, and reliable. I believed in the product. I could redline every shift, hit every curb, and know the car would take it.”

His favorite? The 997-era 911s – narrow-bodied, analog, and brutally fast. “They weren’t full paddle shift yet, but they made proper downforce. Every year we went faster. It felt like an arms race.”

ACO USA

To learn more about or to become a member of the ACO USA, look no further than www.lemans.org, Click on English in the upper right corner and then click on the ACO members tab for Club Offers. Once you become a Member you can follow all the action on the Facebook group ACOUSAMembersClub; and become part of the Legend with future Evening With A Legend meet ups.

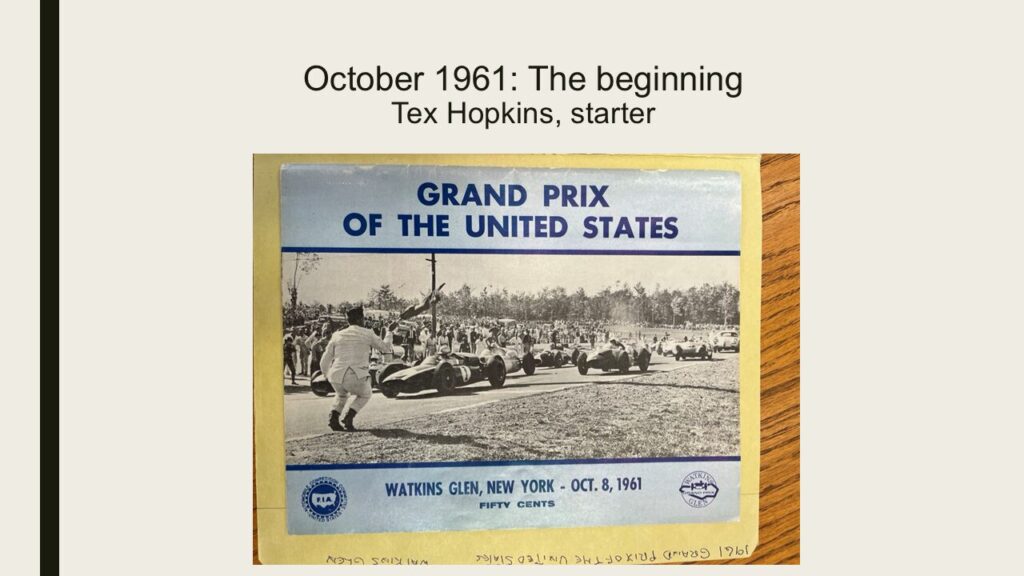

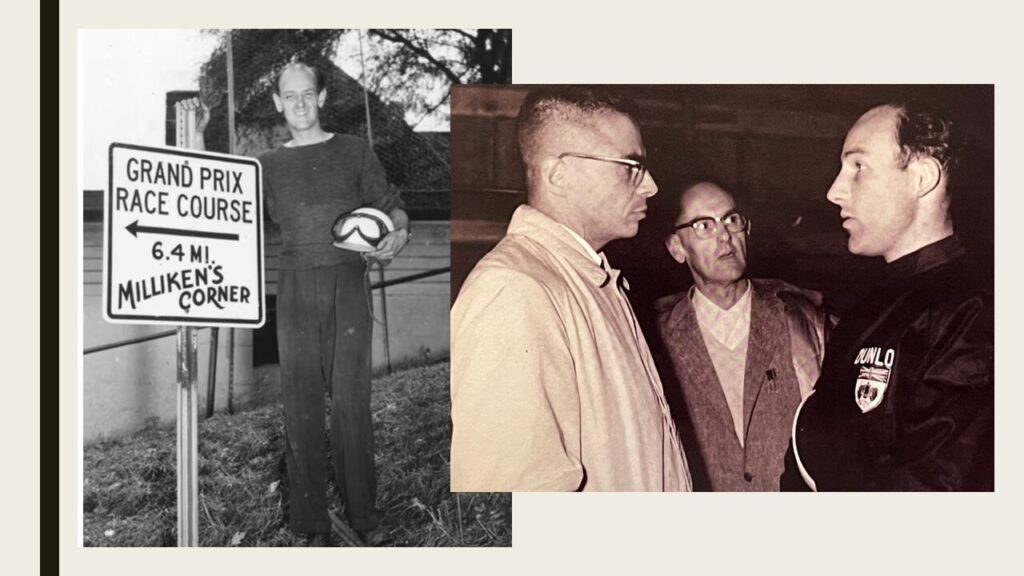

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes:

The symposium is named in honor of Michael R. Argetsinger (1944-2015), an award-winning motorsports author and longtime member of the Center's Governing Council. Michael's work on motorsports includes: